Cultivating loving-kindness

02 Awakening the Kind Heart - 2020 retreat

Part of a series of talks by Venerable Sangye Khadro based on her book Awakening the Kind Heart given during a retreat at Sravasti Abbey in November 2020.

- Introducing the prayer of the Four Immeasurables

- What does “Immeasurable” mean?

- Loving-kindness: the first immeasurable

- Cultivating the state of mind that wishes for the happiness, and causes of happiness, of oneself and others

- Obstacles to loving-kindness and remedies

- Benefits of loving-kindness

- Reflecting on forms of happiness and their causes

- Meditating on loving-kindness

We will continue with our exploration of this topic of how to be more kind by way of what are called the four immeasurable thoughts. This morning I gave an introduction to Buddhism in general and working with the mind, and so now I’ll start talking about the actual four immeasurables. There are a number of prayers in the Tibetan tradition that express these four immeasurable thoughts. The prayer we recited earlier is:

May all sentient beings have happiness and its causes.

May all sentient beings be free of suffering and its causes.

May all sentient beings not be separated from sorrowless bliss.

May all sentient beings abide in equanimity, free of bias, attachment, and anger.

There are other versions of this prayer containing the four immeasurables. There’s a longer version that I’ll talk more about later. And somebody just sent a question in about why it is that there are there are different orders in which the four immeasurables come in the different prayers. I don’t know why. I don’t know the origin of these prayers and whether they were composed by individual Buddhist masters, or in what context they were composed. I don’t really know. But later on we’ll talk about the order of the four immeasurables. I don’t think it has to be a fixed order that everybody has to use all the time.

I think the order can vary, maybe according to individuals, according to the way your teacher teaches you, and so on. I don’t think that’s something we need to worry so much about right now. Let’s go through the four immeasurables, and I’m going to go through them according to the order in this short prayer, which is first loving-kindness, and then compassion, and then joy, and then equanimity.

In the Tibetan tradition these four are called immeasurables; they are immeasurable thoughts or attitudes. And there are a few reasons why they’re called immeasurable. One is because when we cultivate these, ideally we cultivate them for all living beings, rather than just a limited number of beings. And it’s said that the number of beings in the universe is immeasurable. There are so many they can’t be counted. So, we are trying to cultivate immeasurable love, for example, in the sense of love towards an immeasurable number of living beings.

And it’s the same with the other three. So, that’s one reason for the term immeasurable. It’s also said that when we even just try to cultivate these four attitudes, we create an immeasurable amount of merit or positive energy. They’re extremely beneficial, virtuous, positive. So, we create a lot of good energy or good karma, we could say, and that’s immeasurable. And also when we cultivate them we purify an immeasurable amount of negative energy, like negative karma created in the past.

Even just trying to cultivate loving-kindness for all living beings is such a wonderful, powerful, positive state of mind. So, it really works against negative energy such as hatred—especially hatred and anger—and any kind of negative thoughts and feelings that we might have towards others. It also purifies negative things we’ve done in the past towards other beings—harming them and so on. So, we’re able to purify an immeasurable amount of negative energy.

In the Theravada tradition, the Pali tradition, they are usually called the four Brahma-viharas. And that term is sometimes translated as divine abodes. Brahma is the name of a deity. It’s a Hindu deity, but Buddhism believes this being does exist. And he’s in the form realm, which is another realm. We are in what’s called the desire realm because we have so much desire. We’re just crazy with desire here. But there’s another realm of existence called the form realm. And it’s called that because they have the forms—the objects of perception there—are said to be incredibly wonderful, sublime.

And they’re free of many of the kind of faults and negative attitudes, negative behaviors, that we experience in the desire realm. For example, there’s no anger there. Nobody gets angry or has hatred. And also the ten non virtuous actions, like killing, stealing, and others, never happen. Nobody ever does those. So, it’s a really nice, cool place to be. And so Brahma is the name of this deity who rules over an area of that realm. And because the beings in that realm have minds that are so subdued, calm, peaceful, and pure, then because they have a lot of these qualities—love and compassion and so forth—then when we ourselves try to cultivate these states of mind, our mind becomes like the minds of the beings in that realm. Our minds become like the minds of the beings in the Brahma realm, the form realm. So, it’s like we are abiding—mentally at least—in Brahma’s realm.

Introduction to loving-kindness

Okay, so we’ll go through these one at a time. Today I’ll focus on loving-kindness. And the Pali term for this is metta. In Sanskrit it’s metri, which is also the name of one of our Abbey cats. And the Tibetan term is jampa, which is the name of one of our Abbey Venerables. What is this state of mind? It’s explained as the wish for happiness for oneself and others.

When you have this state of mind of loving-kindness, you are wishing either yourself or somebody else or all beings to have happiness, to be happy. And when they talk about happiness in this context, it doesn’t necessarily mean this—whoopee—happy, joyful sort of feeling, but it can include any kind of source of comfort and happiness for living beings. So, for example, it might be food. Everyone with a stomach needs food to eat, and we’re happy when we can have food and unhappy when we can’t. When we talk about wishing sentient beings to have happiness, that includes not just the feeling of happiness, but all the things they need to be happy, such as food, clothing, shelter. Well, animals don’t need clothing, but people do.

Anyway, we wish them to have whatever is needed according to their particular needs and wishes—whatever they need in order to be comfortable, safe, and mentally calm and happy. And it’s said that the best example of this feeling of loving-kindness is the love a parent has for their child, especially when the child is very small and quite vulnerable and needy and dependent on others for its survival. Mothers and fathers who bring a child into a world are really devoted to their child. They see their child as really, really precious, and they’re just so attentive to the child’s needs. Of course, that’s not always the case 100% of the time, but I’m talking here about a best-case scenario, a healthy, functional family. So, they really are totally dedicated to taking care of their child’s needs, protecting it, making sure it’s comfortable and happy and safe and doesn’t run into pain and problems and difficulties.

This kind of love is pretty much unconditional because a small child is not able to give much in return, although parents would say otherwise. They say, “No, I get so much from my child,” but that’s more in terms of their own satisfaction. It’s pretty much one way, I think, especially when the child is small. It’s so needy, so they’re just totally giving to the child without asking anything. They’re not asking the child to pay for the services they are giving. It’s volunteer labor, a labor of love.

And so it’s probably as unconditional as you can get in human relationships because when it comes to adults’ relationships between adults, they’re much more complicated and come with a lot more expectations: “I’m not going to love you anymore because you’re not doing what I want you to do,” and that kind of thing. It’s not so unconditional. So, that’s the usual example given of this kind of love: the love that a mother or father has for their small child. Myself and some other Buddhist teachers tend to use the term loving-kindness as opposed to love because the term love can be so complicated. It gets into romantic love and sexual love.

Loving-kindness is perhaps stressing more that it’s love in the sense of treating others with kindness and not so much using the other person as a source of one’s own satisfaction and needs and so forth. But even so, some people aren’t so comfortable with any kind of connotation of love. I’ve heard some people say, “Love? It sounds kind of sentimental, mushy.” Other terms that could be used in place of love or loving-kindness could be friendliness, care, concern, or simply kindness. So, if you’re not so comfortable with the terms love or loving-kindness, you can pick one of those other words. The important thing is to get in touch with the meaning of that word.

It’s talking about a particular state of mind. It’s a state of mind we all have at least at certain times with certain people and certain situations. If you’ve had the experience of being a parent then you would know that feeling towards your child. But another good example of that would be the feeling we have towards pets. Many people have pets, and I think that’s another good example because pets, like little cats and dogs and so on, they’re also kind of vulnerable, just like children. They need a lot of care, a lot of attention. They’re very much dependent on us, and they don’t ask so much in return as long as they have a bowl of food and water and a place to sleep. It’s, again, kind of uncomplicated—not so complicated like other kinds of relationships can be. I think it’s relatively easy to feel this kind of fondness and affection towards animals, pets.

I’m sure everyone can think of times or cases where they’ve had that kind of feeling either towards a small child, towards a pet, towards a little animal, towards friends, towards siblings, towards parents. So, when we see that other person or that other being as dear to us and precious and we care about them and we’re concerned about them and we want to take care of them, we want to do what will bring them happiness so that kind of feeling. It’s something that will just arise naturally, spontaneously sometimes, but the idea in Buddhism is that we can cultivate this state of mind so that we can feel it more often and for more people and beings and get to the point where we can feel it for everyone every being without exception.

That’s the meaning of immeasurable loving-kindness. And it may sound impossible, but it’s not. It’s just a question of time and effort and energy. You have to put energy into it, but it’s possible. And it’s very worth doing, very worthwhile, because there are lots of benefits. I’ll talk about those a little later. There are benefits that we experience, benefits that others experience. So, it’s good for us, but it’s good for us and good for others. It’s a nice thing to have.

Obstacles to loving-kindness

So then the traditional teachings, at least in the Pali tradition, talk about these obstacles to loving-kindness. And this is true for each of the four immeasurables. There’s said to be a far enemy and a near enemy. In the case of loving-kindness, the far enemy is hatred and variations of hatred, such as anger, aversion, impatience criticalness, judgmentalness, irritation. It’s those states of mind. It’s like opposite of love, the opposite of kindness.

This is normal. It’s normal to have these feelings. So, don’t feel bad. But there are things we can do to remedy those feelings. There are obstacles, because when anger or hatred or aversion come up in the mind, it’s not possible at the same moment to have loving-kindness. Those are like two opposite states of mind. It’s impossible for the mind to have both of those states of mind at the same time for the same person. As long as anger, hatred, aversion are there in the mind, it’s not possible to have love as well. So, it’s like an obstacle.

Overcoming anger

And so if we do wish to have more loving-kindness, we need to know how to deal with anger. One thing that’s helpful is to recognize the disadvantages of anger and hatred. There are lots of those. Just in the moment that we feel anger or hatred, it’s so painful. It’s so unpleasant. It’s helpful if we can kind of take a step back from our mind and just look at that state of mind and ask ourselves, “Is this nice? Is it nice to feel this way? Do I want to feel this way more and more? Or would I like not to feel this way?” I think it’s easy to see that it’s unpleasant. It brings an immediate feeling of unpleasantness and painfulness. It’s also bad for us physically.

I’ve heard doctors and scientists do research on the effects of anger on the body and our health, and they find it’s bad for us. With your heart, for example, it can lead to heart disease and other kinds of ailments that shorten your life. Also, when we’re in an angry state of mind before we go to sleep, it’s very hard to fall asleep. You’re kind of wide awake with all these angry thoughts, so you can’t get to sleep and even if you do fall asleep, you might wake up in the middle of the night with angry thoughts and then again find it hard to get back to sleep. You might have nightmares. It interferes with our sleep but also with other things that we might do, things that we might normally enjoy, like eating, going for a walk in nature, listening to music, being with friends. If you’re in an angry state of mind, are you able to enjoy those things? Can you feel relaxed and calm and happy and enjoy what you are doing? I think if we look at that, we’ll see no nothing is enjoyable when we’re angry.

And then in terms of karma, when we have anger and we act out our anger, we create negative karma that will lead to more suffering—more problems and bad experiences in the future. And it’s also good to look at how it affects other people when we’re angry how do other people feel about that? Do they enjoy being around us? Do we enjoy being around angry people? No, we don’t.

Developing our toolbox

These are just some suggestions as to how we can look at the effects of anger and see that it’s disadvantageous and leads to problems rather than happiness and good experiences. If we can see that then we’ll feel more interested in overcoming anger, in finding remedies to anger. And then there are lots of remedies to anger. I won’t go into all of those, but like I said this morning, there are whole books full of remedies for anger. But one one thing that’s really helpful when we’re angry at another person is to try to put ourselves in the other person’s shoes—or the other person’s mind rather—and understand what’s going on with them.

If we’re angry at somebody, it may be because we don’t like the way they’re behaving—the things they’re doing, the things they’re saying. So, it can be helpful to ask ourselves, “Why do you think they’re doing that? Where are they coming from?” And we can look at our own experiences when we’re behaving that way and ask ourselves, “When I’m behaving that way, why do I do it? What’s going on with me? What’s motivating me?” By doing that, we can understand the person’s not happy; they’re not in a good state of mind. They’re in a bad state of mind. They’re suffering. They’ve got some problem going on.

It could be something from the past, from childhood or an earlier part of their life. It could be something going on in the present that is bothering them, that’s worrying them. Maybe they’re anxious about or upset about it, so they’re not in a happy, clear state of mind. So, they’re suffering, in other words. And if we can understand that, that can soften our mind so that we don’t feel so angry towards them and can instead think, “Wow, this person’s in trouble; this person is unhappy. This person needs help.” Doesn’t it make more sense to try to reach out and help them instead of being aggressive and fighting with them? Doesn’t it make more sense than being angry at them and so on? That’s a very helpful tool or method that can help deal with anger towards another person. It may not always work in every situation, so that’s why it’s good to have a toolbox of different methods. If one method doesn’t work, you try another one. Hopefully you’ll eventually find the right tool that takes care of that particular instance of anger. So, we need to work on anger and hatred in order to have more loving kindness.

Love versus attachment

The meaning of a near enemy is something that can look like the positive state of mind that we’re trying to cultivate but isn’t. It’s kind of fake; it’s cheating. The near enemy of loving kindness is attachment. Attachment, in the case of another person, involves a feeling of possessiveness. You tend to feel my friend, my child, my sibling, or whatever. There’s a possessiveness there, and there’s also a sense of “This person makes me happy. This person makes me feel good. This person fulfills my needs, and therefore I want them to be close to me. I want to be close to them. I want them to be there for me.” It’s almost like using the other person for our own happiness. It can look like love, and also in our close relationships, most of the time there is a combination of love and attachment, and they can be so mixed up that we have a hard time telling them apart.

So, one thing we need to do is recognize the difference between love and attachment. One way of understanding that is that love is focused more on the other person and their happiness, their well-being. Like in the case of a parent with their child, they are focusing on the child and what is good for the child, what is needed by the child. It’s about “What I can do for my child”: that’s love. Whereas attachment is more about me: “What I’m getting out of this?” If wer’e thinking, “The other person makes me happy, makes me feel good, does what I like, and therefore I want to keep them close to me,” then the focus is more on me and my happiness or my well-being. That’s attachment, and it’s most probably attachment that leads to problems in relationships.

When there are arguments, conflicts, tension and so on, all those unpleasant things that can happen in relationships, if we look carefully at what’s going on there, we’ll probably find attachment. “My needs are being compromised. I’m not getting what I want. You’re not doing what I want you to do”—something like that. Is that love? It’s not, but again, the two can be so mixed that it gets sticky. We need to be able to tease them apart and recognize what’s love and what is attachment, and then work on cultivating more love and decreasing the attachment.

Remedies for attachment

And there are lots of remedies for attachment. One remedy is meditating on impermanence because when we have attachment for a person or a thing, there’s this feeling of wanting it to be there forever and not change and not go away. We want it to always be there for me just as I want it, and that’s just not realistic. Nothing is permanent. The people and things that we’re attached to are not permanent; they’re changing all the time. And eventually, at some point, we’ll have to separate from them. Either they will go away or we will go away, but we cannot keep them forever. This is a dreaded thing. This is what many people don’t want to think about, don’t want to face, but it’s better to face it because it’s going to happen. It’s better to think about it beforehand and prepare for it, and so just becoming more comfortable with impermanence, change, and eventual separation and loss helps to reduce the attachment.

It also helps to increase the love, especially with people, because when you realize that person is not going to be there forever, you realize you really need to value them and cherish them and keep this relationship good and beautiful as much as possible before they’re gone or you’re gone. So, that’s a really helpful antidote to attachment.

Another thing that’s helpful is to ask ourselves how we see the person: what is our view and what is our mind saying about this other person? Is it realistic or not? We need to do a reality check because one of the things that happens with attachment is we tend to exaggerate. We tend to make our object of attachment into something much more wonderful, glorious, attractive, necessary or whatever. We kind of add all these qualities onto the object that aren’t there, or we exaggerate ones that are there, so we have an overly exaggerated picture in our mind of the object. This is easy to see when you fall in love because the person just becomes like a god or a goddess, or a movie star, or just something so fantastic and wonderful.

If you can step back from that and ask yourself is this true—”Is the person really like that?”—then maybe you don’t want to admit it, but sooner or later you’re going to come down to earth and realize that they’re not what you thought they were. That can help us to see the person in a more realistic way because everybody has some good qualities and some not so good qualities. When we have attachment, we tend to just focus on good qualities; we exaggerate them ignore or deny any bad qualities. And it’s just not realistic, so it’s better to see the good and the bad and the impermanence so then we’re much more down to earth and have a more realistic view. That can reduce the attachment and increase the love.

Letting go of selfishness

And then another obstacle to loving kindness this isn’t mentioned in the traditional teachings but is something that I see is self-centeredness—being selfish. If we’re really, really attached to me and my needs and my wishes and what’s good for me, and that’s our number one concern and our focus of attention, then that will be an obstacle to really loving others. And again, our relationships will become more like using the other person to get what I want, to fulfill my needs, and not being concerned about them and their needs. Selfishness is just a normal state of mind in us unenlightened beings. We all have it, so don’t feel bad.

And there are remedies—methods we can use to overcome it. One thing that’s helpful is just to do a comparison of the self-centered attitude—”I am number one. I am the most important person in the world”—and altruism, which is where we care about others. We focus on others and are concerned about others and want to help others. We all have both experiences. At certain times we are more selfish, and at other times we are more altruistic. So, just in your own experience, compare those two states of mind and examine the benefits, if any, and disadvantages, if any.

And also, look at others in the world around you: what kind of people are you most inspired by? Is it people who are selfish, narcissistic, egocentric, people who only care about themselves, or are you more inspired by people who have this open heartedness and really care about others? Are you inspired by people who are altruistic and compassionate and kind and concerned about others and doing things for others? I think if we do that, it’s probably pretty clear that altruism is a much better way to be and that it’s better to put our energy into being like that more and less self-centered.

So, those are some obstacles that we may have in our mind that would interfere with the cultivation of loving kindness. As we are trying to enhance and cultivate this quality of loving kindness, if we encounter any of those then there are remedies to them. And the more we can decrease these obstacles then the more space there is in our mind to have loving kindness. But it does take effort; we can’t just sit and wait for loving kindness to pop up in our minds. It might do that sometimes, occasionally, but we can also bring it up more often, and there are lots of benefits that we will experience if we do work on cultivating more loving kindness.

The benefits of loving-kindness

In the traditional teachings there are lists of these benefits. I’ll mention the main ones. One is that our mind will be more happy and will be more healthy physically. I think we can see this in our own experience. When we do have feelings of love, kindness, concern, care, it’s a very nice way to be; it’s a beautiful state of mind, and it feels good compared to anger, hatred, irritation. There’s kind of an obvious difference between those two. And as for our body, if our mind is more positive and happy, then naturally that will affect our health. There is a connection between our mind and our body.

In recent decades, scientists have done research on different states of mind. They’ve researched negative ones, like anger and hatred and anxiety, and they’ve also done research on more positive ones. Mostly I’ve read about where they’ve done research on compassion and found a lot of benefits to compassion, but loving kindness is quite similar. It’s kind of like two sides of a hand or two sides of a coin. Compassion and loving kindness are very close, very similar. I think all the benefits of compassion that have been found in research would apply to loving kindness as well. It’s definitely good for us. And then another benefit is that we will be loved by others. Isn’t that what we all want? We want people to love us, to like us, to be there for us when we need help.

How does that happen? We can’t force people to love us. We can’t pay them to love us. You can try, but it may not be genuine love. If we really want people to love us, if we want people to have genuine love for us, the best way to do that is to be loving towards them to show them love and kindness and affection and to help them. If we give out that kind of feeling, if that’s our attitude towards others, then they will reciprocate. We can see that with the Dalai Lama, for example. He’s such a loving and compassionate person, and he’s so popular. Wherever he goes, people are just dying to get close to him. It’s so funny when I’m in Dharamsala or in Indian teachings, and he’s walking through the crowd to come to the place where he’s teaching, and he’s waving at everybody.

Sometimes an American person will call out, “I love you!” I don’t think Tibetans would ever do that; it’s got to be an America. And also, loving-kindness leads to protection. We want to be helped when we’re in danger or facing some difficult situation, so people will naturally want to take care of us and protect us when we’re in that situation because they see us as precious and important. So, we’ll have plenty of friends and protectors around. Another benefit has to do with our sleep: we’ll sleep well and have pleasant dreams rather than scary nightmares, and wake up refreshed. It’s good to go to sleep with thoughts of loving kindness in your mind, to have positive thoughts as opposed to going to sleep feeling angry, thinking about someone you don’t like, and all these negative thoughts about that person.

If you go to sleep like that, you probably won’t be able to sleep anyway. And you might have nightmares, and you’ll wake up feeling awful. But if you go to sleep with feelings of love and kindness then you’ll have a good sleep, good dreams, and wake up refreshed, and that’s good for our health as well. If you can’t sleep well at night, it’s very difficult to be healthy. The next one is our appearance will be radiant and relaxed and our ability to communicate with others will go well. We’ll be able to communicate easily with confidence; we’ll have nice, smooth, easy communications with others. It will also have an effect on our mind, enabling our mind to be more calm.

And then if we’re practicing meditation and trying to cultivate concentration then that will go better. Our mind will be more concentrated, and I think we can see that ourselves, because if we have a lot of anger and negative feelings towards certain people then when we’re trying to meditate, thoughts of those people we don’t like might come up. And our mind can get totally carried away with negative thoughts and maybe fantasizing about harmful things we want to do to that person and so on. So then how can we concentrate on our object of meditation with that going on in our mind? With more loving kindness then our mind will be more calm and clear in meditation. And then in terms of our work, when we’re trying to do some activity—some project or writing or whatever work you do—again, your mind will be able to focus more clearly easily on the work that you’re doing and be able to accomplish it.

So again, we can see that when our mind is caught up in anger, it’s very difficult to think clearly, to focus. It’s difficult to make good decisions when our mind is crazy with these negative thoughts. So, with less anger, less hatred, and more love then the mind will work better and be more efficient. And then another benefit is that at the time of death, there’s a greater chance that our mind will be peacefu,l calm and clear—maybe even feeling love. If we really train our minds in loving kindness and compassion for others, then that makes our mind very familiar with those thoughts. And even at the time of death, even as we’re dying, then instead of being frightened of death or so caught up in our own concern about ourselves, we’re able to focus on the people around us and express our love for them. It’s a much better way to die than with anger and anxiety.

And then it’s also said that being able to have such a positive state of mind at the time of death will ensure a fortunate rebirth in our next life. The state of mind at the time of death is very very crucial for our next rebirth—if you believe in rebirth. If you have doubt about that then that may not be relevant to you, but for those of us who do believe in another life after this one, then it’s very important that we try to die in a good state of mind. And loving kindness and compassion are the best kinds of thoughts and attitudes to have at the time of death. So, those are benefits of generating and enhancing our loving kindness.

Different kinds of happiness

And then in the prayer of the four immesaurables, the line related to loving kindness says, “May all beings have happiness and the causes of happiness,” so it’s good to think about that. What do we mean by happiness and what are the causes of happiness? I came across a teaching I found really helpful in a book by Aya Khema, a German Buddhist nun and teacher. She said the Buddha explained four different kinds of happiness, so not all happiness is the same. And one kind of happiness is the happiness—or maybe it’s better to call it pleasure—that comes from sensory experiences. We have five senses: seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and tactile or feeling sensations with our body. With our five senses, when we encounter objects that are pleasant, agreeable, enjoyable then we experience a certain amount of happiness of pleasure.

When we see beautiful things, hear pleasant sounds, smell nice odors, taste delicious tastes, feel nice sensations in our body, then there’s happiness. That’s one kind of happiness. But it’s limited; it’s not the best kind of happiness. For one thing, it’s short-term. It may only last a few seconds or a few minutes, maybe a few hours, but eventually it passes. It’s not very long-lasting. Also, in order to have that kind of experience, we are dependent on usually external objects. You have to have something attractive, something beautiful to look at in order to have that kind of pleasure. You have to have nice sounds, nice smells, nice tastes, nice feelings in the body; so, we are dependent on those external objects—the five sense objects—in order to have this kind of pleasure. As long as they are available it’s fine, but they are not always available. You can’t always get these nice objects that give us that kind of pleasure.

Also, there’s a tendency to get bored and dissatisfied with them. For example, when we eat a certain type of food for the first time, we may feel “This is great; this is fantastic.” But if you were to continue eating that food every day, three times a day, the pleasure probably wouldn’t last, and pretty soon you might be sick of it and not want to ever see it again. So, this kind of pleasure is a bit unreliable. Also, there’s a greater chance of attachment when we have these kinds of experiences. We usually get attached to the object that gives us that experience and to the experience itself, so our attachment increases, which isn’t good for us. There arevarious disadvantages to this kind of happiness or this kind of pleasure.

And another kind of happiness is what I like to think of as spiritual happiness. This is happiness that comes from positive states of mind like loving kindness. We can experience this whenever we feel love for somebody1when we’re with someone that we really care about and feeling these warm, caring feelings for that person. There’s another kind of happiness there. It’s not quite the same as sense happiness or sense pleasure; it’s a deeper, more emotional happiness. And maybe we can also experience this sometimes when we’re meditating, and if we’re really enjoying our meditation. We’re feeling happy and contented to be sitting there doing our meditation, doing our practice; we’re not wanting to go anywhere else or do anything else. We’re just feeling like “I’m really happy to be here doing this.”

I would call that contentment. That’s also a kind of spiritual happiness, which is quite different from sensory pleasures. This is the kind of happiness we can experience from cultivating these four measurable thoughts, from meditating on them and increasing them in our mind. Another kind of happiness comes from developing concentration. For example, in the Tibetan ,we have this practice of calm abiding or serenity—shi ne in Tibetan. This is training the mind to stay focused on a single object, the object that we choose. It could be the breath or an image of the Buddha or whatever, and we’re learning to stay focused on that object for longer and longer periods of time. In the process, you overcome various obstacles like laziness and distractiveness and lethargy and so on. You eventually get to where you have this very sharp, clear, alert focused state of mind that’s just staying with your object for long periods of time.

So, when calm abiding is actually attained through that practice, it’s said there’s this incredible physical bliss and mental bliss that’s unlike anything we’ve ever experienced in our life. It’s the best bliss there is. And so, that’s another level of happiness, another level of good experience, that’s available to us, but we have to put effort into it. And then there’s an even better one that comes from cultivating wisdom—the wisdom that understands the true nature of things—because it’s wisdom that wipes out the disturbing emotions in the mind. It gets rid of greed hatred, ignorance, doubt, pride jealousy—all those painful disturbing emotions.

They’re gone; they’re not coming up anymore and jumping around in our mind, so our mind is so peaceful. I’m not talking from experience, but those who’ve experienced that, that’s what they say. That’s an even higher, better form of happiness. I really like this explanation because it shows that there are different kinds of happiness, different levels and degrees of happiness. When it comes to loving kindness, which is wishing happiness for oneself and for others, ideally we wish them to have not just the first kind of happiness. Of course that is necessary, especially when it comes to things like food and clothing and shelter and medicine and so on. If you don’t have those then it’s very hard to be happy, so we do wish sentient beings to have that first level of happiness. But we don’t want to stop there.

Cultivating the causes of happiness

We want them to have the higher levels of happiness as well. This is something we can gradually cultivate as we work on loving kindness—thinking about what kind of happiness we wish others to experience. “I want them to have higher and higher levels of happiness, all the way up to the highest happiness, which is enlightenment, Buddhahood.” And then we’re wishing sentient beings to have not just happiness itself but also its causes, and for me, that was really powerful to think about. Because what are the causes of happiness? Where does happiness come from?

It seems like having food, clothes, shelter, medicine, money, and so on are the causes of happiness. But Buddhism says it’s deeper than that. The real causes of happiness are virtuous states of mind, positive states of mind, like love, compassion, generosity, wisdom, contentment, and so on. So, it’s all the positive qualities, the virtuous qualities of the mind and also virtuous actions, good karma. Earlier this morning I was talking about the causes of suffering. The causes of suffering are negative states of mind, afflictive states of mind, like greed, hatred, ignorance, and then the actions that are done motivated by those states of mind. Those are the main causes of suffering, so the causes of happiness are the opposite. They are the positive states of mind, the virtuous states of mind, and then actions that are done under the influence of virtuous states of mind, such as the ten virtuous actions. It’s any kind of virtuous action really: helping others living ethically, being generous, engaging in spiritual practice, and so on.

If we really want sentient beings to have happiness, we wish them to also have the causes of happiness. It’s like when aid agencies and NGOs and so on are working with people who are impoverished, people who are having a really difficult life—it’s not enough just to keep giving them food and money and building houses for them. It’s best to teach them how to take care of themselves, to tech them how to become self-sufficient with good farming methods, good health care methods, good parenting methods, and so on. They are teaching them how they can improve their own lives, how they can improve their own situations. It’s kind of similar here when we think about sentient beings and what’s the best thing for them. Of course we wish them to have food and clothes and shelter and so on, but we also want them to learn how to create their own happiness. We want them to learn how to create happiness for themselves by having positive states of mind, virtuous states of mind, and engaging in virtuous actions.

I remember one time when I was staying in a very impoverished part of India. A lot of the villagers come because there’s tourists and pilgrims in this area with money, and so they come and line up and people give them money and food and so forth. There was one woman who was begging from an English monk, and he held out his hand and asked her for something. I think she had some stuff in her bowl, and so he somehow wanted to reverse this situation. It wasn’t because he wanted something from her, but he wanted her to be able to create the merit of giving. I think she was really confused, but this is what they are doing all day long: “Give me, give me, give me give me, give me,” so he wanted to somehow help her to give to practice giving. If she could give to a bhikshu then this would be incredible merit for her to create the cause for happiness in the future.

I find this really powerful to think about; this is the best way to help sentient beings by providing the conditions for them to be able to create the causes of happiness. We can’t force that on them, but it’s helpful just to think in terms of how how can I help sentient beings to generate these positive states of mind and engage in positive actions so that they can get themselves out of the suffering situations that they are in. There is a lot to think about here when we are doing loving kindness meditation. Wishing happiness for others can really get very creative. Buddhism says every sentient being wants to be happy; this is a basic feeling, a basic attitude that we share with all living beings.

Wanting happiness is not wrong

Deep down inside, everyone wants to be happy; everyone wants their needs fulfilled. They want their basic needs fulfilled and whatever they need to be comfortable and happy and secure and feel loved and so on so. Everyone has that basic wish and also everyone deserves happiness. Happiness is something we all deserve. Nobody should have to suffer, and so there is nothing wrong with wanting happiness. It isn’t selfish or greedy or deluded to have the wish for happiness. That may sound obvious, but I had to give myself a talk and say, “It’s okay to want happiness. It’s okay to have happiness. It’s not wrong; it’s not bad; it’s not selfish; it’s not greedy.”

I remember teaching in London once, and I talked about this. And one woman was like, “Really? Buddhism says that?” She was incredulous; it was something she hadn’t heard before, and she had doubt about it. It kind of shows that there’s something in the U.S.—maybe it’s our Judeo-Christian culture—that might teach us we shouldn’t wish for happiness and should suffer instead. That’s a bit exaggerated, but there can be this feeling of “I shouldn’t want happiness; that’s selfish. That’s greedy.” And if we feel that way about our own wish for happiness then it’s quite likely we’ll project that onto others as well. It’s actually kind of cruel. There’s a sort of cruelty there, so look out for that—see if that’s something that might come up in your mind. And I think that could be another obstacle to loving kindness.

If you do notice it, just say to yourself: “Buddha wants us to be happy. It’s not wrong; it’s not bad. We should be happy.” I remember Lama Yeshe saying that to us when I was living at Kopan Monastery with a small group of Western monastics. He would sometimes say to us that you should be happy: “Whatever it takes, I want you to be happy.” I think he could see we were thinking too much about the hell realms and the eight worldly dharmas. He wanted us to be happy and smiling; it’s just how to have happiness. We have to go about getting happiness in the right way, not in the wrong way: by cultivating positive states of mind and ethical behavior. Those are the real causes of happiness.

How to meditate on loving-kindness

When it comes to how to cultivate loving kindness, there are different meditations. I’ll explain the usual one that you can do in the morning or on your own in case there are people who are new to Buddhism and meditation in the Tibetan tradition. There are two general forms of meditation. One is called placement or stabilizing meditation, and that is when we have an object that we train our mind to stay focused on; we could also call it concentration meditation. To keep it simple, we are training our ability to concentrate, and the object you use could be almost anything. Buddha recommended certain objects, such as the breath—the breath is an easy one. Or you might use an image of the Buddha. When you have an object, you sit down and focus your mind on that object, and then you keep coming back to that object whenever the mind wanders away.

If you keep working at that then eventually you can achieve what I just talked about earlier: calm abiding or serenity—single-pointed concentration. That’s one form of meditation. The other one is called analytical meditation. Lama Yeshe used to call it checking meditation, and this is where we are thinking about an object to try to understand it better and deepen our understanding of that object. So, for example, the four noble truths; they are meant to be meditated on. With the first noble truth, the truth of suffering, we use analytical meditation to meditate on that. The Buddha himself mentioned some examples of sufferings, and we can find other examples as well, but we meditate on these different kinds of suffering in order to realize that the world we are in is not satisfactory.

By that, I don’t mean this planet earth but samsara in general. As long as we are not enlightened beings, as long as we are in this situation, we will experience unsatisfactory experiences again and again and again. It’s just the nature of this situation of samsara. And the purpose of this is not to become depressed and miserable but to generate the wish to get out—to see that we are not in a good situation and that we’ve got to get ourselves out of this situation. We do that by seeing all the different disadvantages and painful experiences and unsatisfactory experiences.

So, that’s an example of analytical meditation where you’re bringing to mind examples of different types of suffering and looking at your own and others’ experiences and so on, just to get a better understanding of the unsatisfactory nature of samsara. And we do this in order to generate the wish to get out and do what you have to do to get out, so there’s more thought involved, thinking and imagining and visualizing and remembering and so on. When it comes to meditations on these four immeasurable thoughts, it’s mainly the second type of meditation that we use.

So, to cultivate loving kindness, for example, we bring to mind different people, different beings, and contemplate that they want to be happy just like I do, and we think, “May they be happy, and may they have this kind of happiness and that kind of happiness.” We’re using thought and we can also use visualization. It’s good to picture the people that we’re meditating on. The most common meditation for cultivating loving kindness involves bringing to mind different people, and it’s good to do one person at a time. It’s more powerful than a whole group of people. It’s more powerful if you really focus on one person at a time and really contemplate this is another human being just like me, and they want to be happy, and how nice it would be if they could be happy, so may they be happy.

There are different ways of explaining it in the Pali tradition. There’s a 5th century Indian master named Buddhagosa who wrote a text called Path of Purification, and that’s the main source of information about how to meditate on these four states of mind. What he recommends is start with yourself first, to cultivate loving kindness for yourself, and then move on to someone you respect, a person that you like and feel respect for. It’s recommended that you avoid someone you’re sexually attracted to because otherwise attachment could come up and gets very messy. Again, it’s hard to distinguish between attachment and love, so it’s better to think of just someone you respect, which could be a teacher or maybe a parent. That’s the second person.

The third person is a friend, someone you care about. And then next would be a neutral person, meaning someone you don’t really like but you don’t really dislike. Your feelings are more neutral, so you could just take a stranger—just think of somebody walking down the street who you don’t know or somebody at work. Think of someone whose photo you see in the newspaper—just someone you don’t know at all. Your feelings are neutral. And then finally you focus on a difficult person, someone towards whom you have negative feelings. So, you’re kind of starting with easier and going to more difficult ones, and it’s somewhat similar in the Lamrim Chenmo.

Lama Tsongkhapa, in the section on cultivating love, mentions the order for meditating on love. He leaves out self; there’s no mention of self. So, you start with friends, people you like and have good feelings for. And then you go to neutral beings and then difficult ones and then eventually all beings. So, it’s kind of similar except for leaving out one’s self. And now many Tibetan teachers understand that Westerners tend to have a lot of self-hatred. When the Dalai Lama first heard about that, he was amazed and said he’d never heard of such a thing. But now he knows, so he talks about it. He talks about how important it is that we have love and compassion for our own self.

But Ajahn Brahm, an English monk living in Australia who has lots of YouTube videos and is very funny, says when it comes to yourself maybe that’s the hardest one, so you put that one last after the enemy. I don’t think there’s a fixed order where you put yourself. You can try different ways: try putting yourself first, and if that’s too hard, put yourself later, because that really makes a lot of sense. If you start with easy ones, you bring to mind people you already like then your mind kind of gets warmed up and more acquainted with loving kindness. Then you bring yourself in. It might be easier.

And he also says it’s good to start with really easy objects, like puppies and kittens. Some people do have trouble bringing up a feeling of love; it doesn’t come up so easily, so it is helpful to think of some being that does naturally bring that up. Not everybody likes puppies and kittens, but I do; just looking at a photo or thinking of a puppy or a kitten—they’re so cute, so adorable. And it’s just so easy to feel that I want to take care of them. There’s probably a lot of attachment there, but at least it does bring up this feeling of preciousness and care and wanting to take care of something, so that’s actually a good way to start the meditation. Think of someone or some being that does trigger that feeling of loving kindness and then you know what you’re talking about. You understand, “That’s the feeling of loving kindness,” and then you extend that to these different beings.

And in the Pali tradition, the Theravada tradition, it’s recommended that we recite these phrases. The recommended ones are just saying—if you’re starting with yourself, for example—”May I be happy. May I be free of suffering. May I be free of animosity, affliction and anxiety. And may I live happily.” Those are the verses from Buddhagosa’s text, but you can use your own words—whatever works best for you. But they’re just some positive thoughts, some good wishes for yourself and for others. So, make your phrases and then repeat those again and again. And it’s not enough just to say the words; we’re trying to feel it. But sometimes the feeling doesn’t come so easily, so if we say the words and keep saying the words, sooner or later the feeling will come.

The importance of patience

This is another thing, too: people sometimes say they did a meditation on loving kindness but they didn’t feel anything. That’s actually normal. It may not work the first time, and it may not work the tenth time. It may take a hundred times before you actually feel something, so don’t give up if you don’t feel something right away. Just keep doing it, just keep saying those words to yourself and really contemplate those words: “What am I saying? What am I meaning?” Eventually the feeling will come, and it will start to come more easily.

In fact, I saw a talk by this one Buddhist teacher, and he was saying he had a rough life before he got into Buddhism. And then I think he was learning from Sharon Salzberg; she wrote a wonderful book quite a long time ago on this topic called Loving Kindness: the Revolutionary Art of Happiness. It’s mainly about loving kindness, but she does talk about the other three as well—compassion and so on. She’s got a lot of experience practicing and teaching these methods, and so this guy was a student of hers and learning from her. And he was saying that for a long time he was just doing the meditation and just saying these words but feeling nothing. It took five years of this practice before he meant the words. He was just saying the words but not really meaning it. It took him five years to get to where he meant what he was saying, but then he still didn’t feel anything. It took another five years before he could actually start feeling the loving kindness.

I thought, “Wow, what persistence, what commitment—to keep practicing it even though the feeling wasn’t coming.” Hopefully it won’t take that long for you, but it just shows that if we keep working at it, eventually whatever obstacles there are to feeling those feelings will melt away, and the feelings will start to come. And even if they do start to come, they may not come every time, so don’t expect that either. Sometimes they may come and sometimes not, but it’s still worth doing doing this practice, trying to generate those feelings, saying those words.

Lama Tsongkhapa also mentions that we’re doing the meditation another thing we can do—and I find this really nice to do when you’re thinking of a person and generating loving kindness for them—is to imagine giving them things that will make them happy. We imagine giving them the food they like to eat, giving them a bouquet of flowers, giving them a nice warm shawl if they’re cold. So, we give them things that will make them happy and then it becomes much more juicy than just sitting there thinking, “May you be happy, may you be happy.” Let’s do something to make them happy, at least in our imagination. That helps, too, to bring up that feeling, to make it more real and genuine.

And in terms of time, this is a practice you could spend hours doing if you have the time, but not many people do have the time, so even if you just spent 5 minutes doing it, it’s still something. You’re still making yourself familiar with this practice. You don’t necessarily have to do all the different individuals, all the different types of people, in one session. Maybe one day you could do yourself, and the next day a friend, and the next day a new person. Switch it around. And also, you don’t have to only do it when you’re sitting and doing formal meditation, but you can do it when you’re at work or traveling on a bus or train or driving. When there are people around me, we can think: “May they be happy. How nice if they could be happy. I wish them to be happy”—something like that.

That just takes a few minutes or maybe even less than a minute, and you’re still acquainting your mind with that feeling. And it feels good, too. You can really switch your mind around from a grumpy state to a positive state, so just whatever you’re able to do, however much time you’re able to spend, however many people and beings you’re able to do it for, it’s all good. It’s all helpful to familiarize your mind with loving kindness.

Love for those we find difficult

Now, the difficult part is the so called enemy: the person you dislike. We might need to do extra things to overcome aversion and judgmentalness and so on. I’ll read something from the Buddha; it’s actually about patience, but patience is an antidote to anger and hatred. So, if we can overcome anger and hatred, there’s more space in our mind to be able to feel love loving kindness. This is what the Buddha says:

One’s patience should be strengthened by thinking those who have no patience are afflicted in this world and do actions that lead to affliction in the next life. So, the person you’re angry at is probably suffering now and will suffer in the future because of the actions they’re doing. One should think, ‘Although this suffering arises because of the wrong deeds of others, my body is the field for that suffering, and the actions which brought it into being are mine.’

So, if somebody’s doing something harmful to us, of course we naturally feel angry and want to retaliate, but remember: we are the object of that person’s anger, and so we are partly responsible for this situation. Our karma brought us into this situation, and we have the karma to be harmed by this person so we can take some responsibility for this situation. And then he says:

One should think, ‘This suffering will free me from the debt of karma.’

By going through this painful experience of someone harming us, that karmic debt gets cleared away. I have less bad karma in my mind.

One should think, ‘If there were no wrongdoers, how could I bring patience to perfection?’

So, this guy is actually helping me to practice patience. How could I practice patience if I didn’t have people like that?

One should think, ‘Although he is a wrongdoer now, in the past he may have been my benefactor.’

We could even think of times in this very life where that person was helpful to us and did good things. And if not in this life then in a past life: everyone’s been our mother and our father and helper in past lives.

One should think, ‘A wrongdoer is at the same time a benefactor because through him patience can be practiced.’

That’s similar to before: this person is actually helping me to increase my patience, helping me to cultivate patience.

One should think, ‘All beings are like my own children and who would get angry over the misdeeds of one’s own children?’

Parents might, but the anger that comes up at children is usually anger that comes and goes very quickly. It doesn’t last, so maybe there’s a moment of anger, but then the love is so strong that it comes back and you forgive them. So, that’s helpful, too, to think, “Everyone’s like my child.” In fact, in past lives, everybody has been our child. We’ve been the mothers and fathers of everybody; they’ve been our children, too. We’ve loved them. We have had incredible love and compassion for every single being in the past. You can’t remember that, but just imagining that might be helpful.

One should think, ‘He does me wrong because of some fault in myself. I should strive to remove this.’

We can take that opportunity to look at oneself and ask, “Am I perfect? Am I free of faults?” We’re probably not, so this is an opportunity to look at that and work on that. So, these are just some sayings from the Buddha that can help us to deal with hostility, anger, hatred towards others and to make more space in our mind for loving kindness.

Audience: Someone wanted to know the name of the book that you mentioned.

Venerable Sangye Khadro: It’s called Being Nobody, Going Nowhere by Ayya Khema.

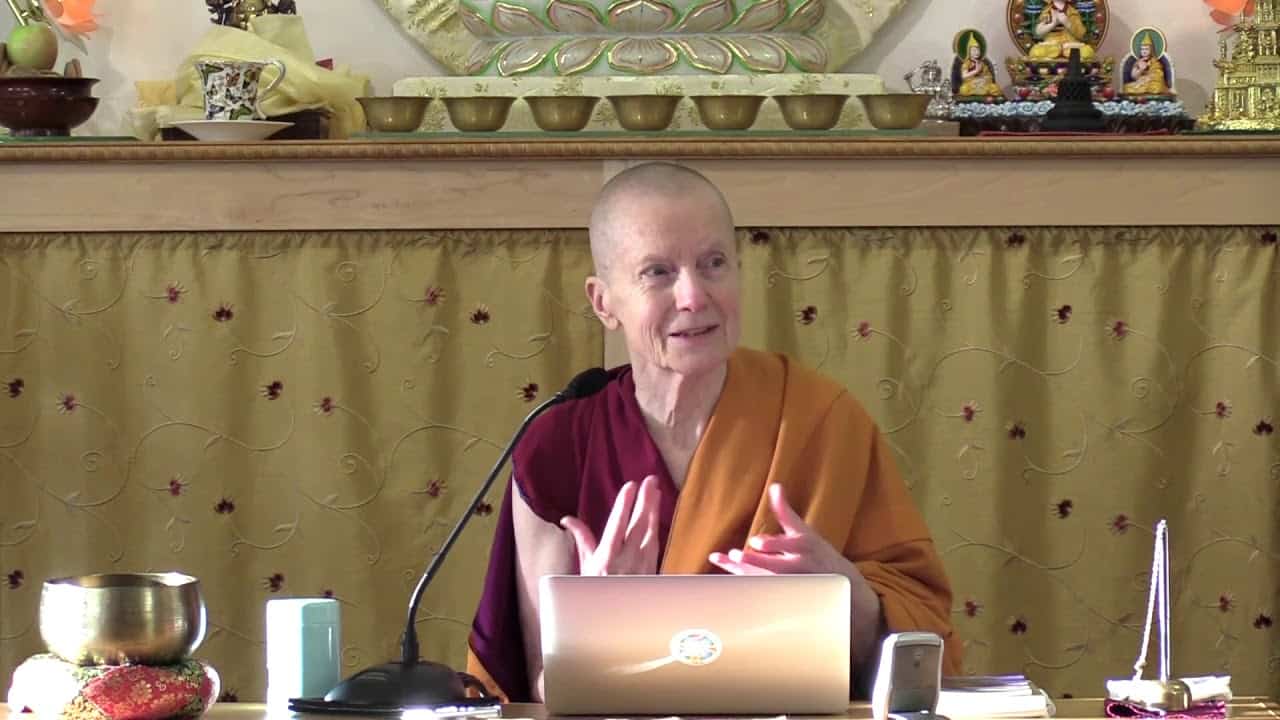

Venerable Sangye Khadro

California-born, Venerable Sangye Khadro ordained as a Buddhist nun at Kopan Monastery in 1974 and is a longtime friend and colleague of Abbey founder Venerable Thubten Chodron. She took bhikshuni (full) ordination in 1988. While studying at Nalanda Monastery in France in the 1980s, she helped to start the Dorje Pamo Nunnery, along with Venerable Chodron. Venerable Sangye Khadro has studied with many Buddhist masters including Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey, and Khensur Jampa Tegchok. At her teachers’ request, she began teaching in 1980 and has since taught in countries around the world, occasionally taking time off for personal retreats. She served as resident teacher in Buddha House, Australia, Amitabha Buddhist Centre in Singapore, and the FPMT centre in Denmark. From 2008-2015, she followed the Masters Program at the Lama Tsong Khapa Institute in Italy. Venerable has authored a number books found here, including the best-selling How to Meditate. She has taught at Sravasti Abbey since 2017 and is now a full-time resident.