Why monastics matter in the modern world

The letter was from a person in prison serving a short sentence for residential burglary and violation of a no-contact order. A crime, but not a violent one. However, he seethed in anger because his “friend” was having an affair with his wife and had raped his daughter. His letter told of his uncontrollable rage and desire for revenge that ate at him. Daily he would plan how to kill the “friend” and his wife once he was released from prison.

Students in Russia offering a khata.

Fortunately, at the suggestion of a Buddhist practitioner in prison, he read my book Taming the Mind and the unimaginable happened—he was able to forgive them. His letter closed by thanking me for writing the book, and the chilling sentence, “Thank you for helping me not become a murderer.”

This is why monastics matter in the modern world.

Without being a monastic, I never would have had the time or circumstances necessary to study and practice the Dharma or write a Dharma book.

Our Teacher, the Buddha, was a monastic. This in itself speaks volumes about the importance of the monastic way of life, training in ethical conduct, concentration, wisdom, and compassion.

Before discussing how to strengthen the sangha—the monastic community—we have to know what value it brings to contemporary society. While monastic life is of incredible benefit to individuals who ordain, here I will explore the roles of the monastic community in modern society. These roles include:

- preserving Dharma teachings and passing them on to future generations;

- being a visible presence of people keeping ethical conduct and cultivating loving-kindness and compassion; acting as the moral conscience of society;

- setting an example of finding happiness through a simple lifestyle that is respectful of the environment;

- establishing monasteries and other places where teachings, spiritual counselling, and supportive spiritual friendships are found;

- establishing central places for Dharma texts, sacred objects, and cherished spiritual artifacts; and many more.

I’ll use the Sravasti Abbey where I live to illustrate some of these points because this is the situation I’m most familiar with. However, there are many more temples and monasteries that excel in these areas and are better examples.

Preserving the Buddha’s teachings and passing them on to future generations

Historically, learning, preserving, and teaching the Dharma so that the Buddha’s teachings will be sustained from one generation to the next has been the responsibility of the sangha community. From the early days bhāṇakas—monastics whose duty it was to collect and memorize the sutras—not only passed the textual lineage from one generation to the next but also taught the Dharma to monastics and lay practitioners alike. Once writing became popular, it was the monastic community that edited and printed the scriptures and wrote commentaries on them. Contemporary monastics not only memorize scriptures but also have taken the lead in digitizing them, contributing to the global study and translation of the sutras and commentaries.

In all centuries and in all lands, the vast majority of teachers have been monastics as have been the majority of meditators in all Buddhist traditions. In this way monastics pass on the transmitted Dharma—scriptural study and education—and realized Dharma—the realizations in the mindstreams of practitioners. Regarding the transmitted Dharma, in addition to teaching disciples at their home monasteries and Dharma centers, many monastics travel to places where the Dharma has not yet spread or had once spread, but declined. Some monastics set up Buddhist institutes to educate the sangha and Buddhist and/or secular universities with Buddhist studies departments. In addition, many monastics, monasteries, and temples have websites where video and audio recordings of teachings are freely available. This spreads the Dharma far and wide in a way that was not previously possible.

This does not diminish the fact that throughout the centuries there have been excellent lay teachers and practitioners who have gained realizations and attained awakening. Rather, it emphasizes that monastic life provides the optimum situation for learning, practicing, and teaching the Buddha’s liberating message. Why is that? Monastics have more time to devote to the Dharma because they do not marry or have children. Providing financially for a family, raising children, and fulfilling social and family obligations consumes a great deal of time. In contrast, the daily schedule in a monastery is based on Dharma study, practice, and service. The fact that there are scheduled periods for Dharma lectures and study, memorization, meditation, teaching, and serving the public means that all these activities get done. Monastic structure also integrates the Dharma in daily activities such as eating meals; there is no way to forget to offer our food and dedicate for our benefactors because the entire community chants together before and after meals.

A visible presence of people keeping ethical conduct and cultivating loving-kindness and compassion

We read accounts in the sutras of people who first became interested in the Buddha’s teachings and later became his followers by merely witnessing the way the Buddha’s disciples carried themselves with humble dignity. Living in pure precepts changes a person’s comportment. By abandoning the wish to harm others, he or she becomes humble; by having the confidence of a person who can control his or her afflictions, she gains dignity. When we come in contact with such people, we not only feel safe, our mind is uplifted and our heart gladdened simply knowing such people exist.

In addition to ethical conduct, which is the basis of monastic life, if a person has cultivated loving-kindness and compassion, an air of friendliness and ease surrounds them. We feel relaxed and begin to wonder what the key to her kindness is. All this attracts us to learn the Buddhadharma. In our troubled times when those who are supposed to be leaders in government, business, and education are corrupt and callous regarding the suffering they cause, people easily become discouraged and fall into despair. However, when they come in contact with a person who radiates kindness and the quiet dignity of ethical conduct, their spirits are uplifted. Walking by such a person on the street or striking up a conversation with him or her while waiting in a queue restores our faith in humanity. Since sangha members are easily identified by their robes, the impact of such encounters is more powerful.

I’d like to share some examples with you. An American friend had studied and practiced the Dharma with the Tibetan community in Dharamsala, India for some years and then returned to New York—the city that never sleeps, as it is commonly called. One day he saw a monk on a subway platform on the other side of the station. Just seeing the robes reminded him of the Dharma and how he wanted to live his life, and he immediately ran over to meet the monk.

One day I was on a plane and a man who was a little tipsy came to talk to me. He knew I was clergy of some sort and spoke about his regrets in life. I explained simple Buddhist ideas to him without using Buddhist jargon, and this helped to calm his mind. Another time, a trans-Atlantic flight I was on was postponed and then cancelled. All the passengers were worried about missing their connecting flights and getting where they needed to be on time. I just did what I had to do, and hours later as we all finally boarded the new flight, a woman came up to me and said, “You were so calm during all of this. Watching you helped me to relax.”

While in Taipei for a conference some years ago, the master invited many of her disciples for a meal at a restaurant. We came from different hotels, but exited at the same metro station. Suddenly all around I saw bhiksunis—on the stairs, on the street—and I felt so happy and invigorated to practice. Because monastics are easily identifiable by our robes, such unexpected opportunities to benefit others occur.

The moral conscience of society

Looking at what is happening in the political, business, financial, industrial, and military spheres of our contemporary societies, we see people overwhelmed by mental afflictions, such as greed, anger, arrogance, deception, and cruelty. Their disregard for the well-being of others and lack of consideration of the effect of their actions on others is evident. As the Buddha said long ago, we live in an age of degeneration.

Whether we are monastics or lay followers, no matter what religion we follow, the foundation of a religious life is ethical conduct. But ethical conduct is not the domain of religion alone; it is valued and necessary in secular society as well. For people to live together peacefully, trust is imperative, and ethical conduct—the essence of which is nonharmfulness—is the backbone of trust. On top of that, for individuals and societies to thrive, care and concern for each other are indispensable. Guided by the Buddha’s teachings, monastics are a visible example of people who are doing their best to cultivate ethical conduct as well as love and compassion for all others. They have taken precepts in order to deliberately train their body, speech, and mind to restrain from harming others. They intentionally cultivate the four immeasurable attitudes towards all beings: equanimity, love, compassion, and joy.

By living together in communities governed by ethical principles, compassionate service, awareness of karma and its effects, and wisdom of the ultimate nature, monastics pose questions to society and to the individuals that compose it. We value honesty, shared resources and wealth, mutual respect, and nonviolence—do you? As imperfect as monastics are, we are making effort to train our attitudes and actions to correspond to these universal values—do you think doing this is important in your lives too? As selfish as we are, we are trying to overcome the self-centered attitude that causes harm to ourselves and makes us harm others—how would your life change if you endeavored to do this? What stops you?

Monastics also take the lead in the ongoing dialogue between Buddhism and 21st century developments. Monastics do not eschew the world but seek to engage with compassion and wisdom. They dialogue with scientists and psychologists, participate in interfaith programs, and are involved in their communities through volunteering in prisons, hospices, animal shelters, and youth centers. They also speak up for human rights such as gender equality, racial equality, and so on.

An example of happiness through a simple lifestyle that is respectful of the environment

In our materialistic and consumerist society, success is measured by our wealth, material resources, social status, and power over others. From childhood, we have been conditioned to judge other people and evaluate our self-worth by these standards. The sangha, however, trains to be disinterested in such things. We learn to be happy with wearing the same clothes every day, eating whatever food we are offered, and living in whatever room we are assigned. Learning this is not easy, but it pays off by making our minds more flexible and more easily satisfied.

When others see a community of people living in this way, it challenges their preconceptions and makes them rethink what is important in life. Seeing or spending time with a group of people who are happy and kind even though they live simply makes people question their own values and priorities. They begin to wonder: these people are happy but they don’t have many personal possessions. They are joyful even though they don’t have the latest devices, wear fashion clothing, or drive expensive or flashy cars. They live simply, yet in many ways they seem to be happier than those of us who possess a lot. Is consumerism and materialism really the path to happiness? This type of questioning is so important for us personally so that we can be authentic people. It is essential for society so that we direct our resources and energy into doing what is meaningful—helping each other.

Climate change, environmental pollution, deforestation, endangered species—there are so many areas in which our attitudes and life styles in modern society disrespect living beings and their environments. I believe the sangha should take the lead in showing how to live in harmony with the world around us: how can we call ourselves the Buddha’s disciples if we don’t try to live in accordance with Buddhist values and principles? Here we have room for improvement. We must stop using disposable dishes, cups, and eating utensils, even though it takes more time to wash dishes at large events. We should do all our errands during one trip to town, thus using less petrol and curtailing our carbon footprint. When we need new vehicles, we must get hybrid vehicles and in the future when we can afford them, electric ones.

At Sravasti Abbey we try to do this as much as possible, even though it can be inconvenient and some sangha members have a hard time getting used to this. We do recycle everything that is possible to recycle, and this makes an impression on the lay followers who stay with us. They learn to sort the garbage, to compost table scraps, to reuse containers and plastic bags that they used to throw out, and to carpool.

A place where teachings, spiritual counseling, and supportive spiritual friendship are found

Lay followers benefit tremendously by joining monastics in meditation practice, chanting, and Dharma study. When they visit a monastery for a day or when they stay at a monastery for a multi-day retreat, lay followers experience the taste of tranquillity that comes with integrating the Dharma in their minds. Practicing together with monastics is different than practicing by ourselves at home, where we are easily distracted by household duties. At a monastery they sit in a quiet hall together with monastics who share and encourage their spiritual aspirations. The dedication to the Dharma that monastics embody inspires them.

Because monastics live in communities, there is an easily identifiable place where people know that Dharma study and practice occur. When someone has a personal or spiritual crisis and needs counselling or when a family suffers the loss of a loved one, people can immediately go to a monastery or temple and receive the help they need. While lay teachers also teach and counsel, people cannot to go to their homes whenever they need Dharma help. Their households may be busy with family activities or may not appreciate the intrusion into their personal space. Many lay teachers have jobs and are not available at all hours. Dharma centers are usually open only when activities occur; most do not have a full-time staff who are capable of offering counselling, going to the bedside of a dying person, saying prayers for the recently deceased, and so forth.

Furthermore, having a physical place that focuses on spiritual practice inspires people. Sravasti Abbey receives emails from people around the world who say that remembering there is a group of people living on a hill in Eastern Washington State who are actively cultivating love and compassion gives them hope. Many of these people have never been to the Abbey, but they follow our live and archived teachings online or read our publications. Seeing photos on our website, they have an idea of how we lead our lives and find this inspiring. They know there are people who want to make the world a better place.

A central place for Dharma texts, sacred objects, and cherished spiritual artefacts

Monasteries—especially those built many centuries ago—serve as repositories for Dharma texts, sacred objects, and spiritual artefacts. When practitioners search for a specific text about a practice they do, when scholars seek little known manuscripts, when devotees want to create merit in relation to sacred objects such as stupas, statues and paintings of the Buddha and meditation deities, and when researchers seek ancient religious objects—monasteries are a good place to go.

Some temples and monasteries in Asia host busloads of tourists each day. These tourists, many of whom are not Buddhist, have the seeds of Dharma planted in their minds by seeing holy objects and hearing chanting. Even in the West, where Buddhism is a minority religion, many people visit Buddhist monasteries to see what they’re like. They, too, have Dharma imprints left in their mindstreams by contacting holy objects and talking to monastics. These seeds will ripen in future lives and enable them to encounter and learn the Buddha’s teachings.

How to strengthen the role of monastics

Having discussed the roles of monastics in modern society, let’s return to the topic at hand—how to strengthen those roles. Here I would like to offer some suggestions on how to do this. Many of you may already be engaging in some of these.

- Make a connection with a monastery and go there frequently to listen to Dharma talks and practice.

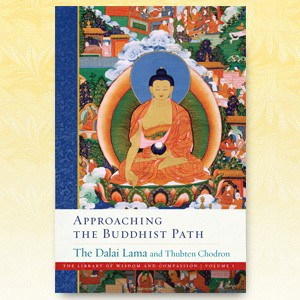

- Help make the teachings given by monastics available to the public by publishing Dharma books for free distribution or purchasing books published commercially so that they can be sent to prison inmates and offered to the poor and others who could not otherwise obtain them.

- Sponsor monasteries’ websites or help to build and maintain them.

- Volunteer to translate monastics’ teachings into other languages.

- Support monastics financially and through volunteering your time so that their virtuous projects to serve society can succeed. A leader who wants to open a day care center, nursing home, hospice, school, Dharma university, youth center, homeless shelter, or counselling center can only do so with the help of others.

- Support monastics who want to spread the Dharma to areas in the world where it does not presently exist. Many countries have little to no Dharma activities, or if they do, temples, monasteries, and centers are not widespread and easily accessible.

- And last, but not least, the best way to support the role of monastics is to ordain and become a monastic yourself! If you have spiritual longing and want to live a meaningful life based on generosity, consider exploring monastic life. If you seek to know the nature of your mind and want to progress on the path to awakening, join the sangha. If you want to see the Dharma flourish in your heart as well as in the world, become a monastic. While a monastic lifestyle is not suited for everyone, for those who want to devote themselves to the Buddha’s teachings, it is a wonderful experience.

Our motto at Sravasti Abbey is “creating peace in a chaotic world.” May the Buddha’s fourfold assembly—fully ordained monks and nuns, and female and male lay followers—work together to create peace in our chaotic world by keeping our precepts well, living with wisdom and compassion, and dedicating our lives to the Three Jewels.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.