How to tell if a Buddhist teacher has the right qualities

- The importance of separating people’s behaviors from the people themselves

- Cultivating compassion for all those involved in a difficult or abusive situation

- The many reasons why harmful situations come about, even in Buddhist communities

- Qualities to look for in a Buddhist teacher, and the importance of examining them

- When (and when not) to take tantric initiations, and what is expected

I’m going to speak a little bit about difficulties that are happening presently in the Buddhist world, especially regarding one particular teacher. The name is not important, and when I speak I’m not speaking solely about this particular situation. In other words, when I talk about possible causes I’m not saying all those causes apply to this situation. I’m just speaking in general. Also, I want to be very clear that I’m speaking about behaviors, and I’m not speaking about people. Somebody’s actions or behaviors are different from the person. We can say actions or behaviors are harmful, they’re inappropriate, damaging, whatever, but we cannot say people are evil, and bad, and hopeless, and so on, because everybody has the buddha potential. I want to be very clear. I’m not speaking about people, I’m talking about behaviors.

There’s a situation in which one very well-respected, very famous lama, who has a big international organization…. It seems to have been going on for many years, and it’s come out in the open from time to time. But especially now some of his students—long-term students who have been with him in the organization for many years—have made some abuse things public. It concerns sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, financial impropriety (or kind of a lavish lifestyle that the students don’t feel is suitable). It’s caused a big hoopla. Especially the students are very confused, which is why I’m giving this talk. It’s to help people who are confused by the whole situation because I’ve gotten some letters from people asking for help. So, it might take more than this one particular BBC.

Also, to preface this, we’re not only talking about behaviors not people, but we’re approaching this from the perspective of compassion for everybody. Clearly the people who have been exploited, or the people who have felt harmed in any way, our attitude is compassion towards them. Not blaming the victim. And also our compassion is towards—whenever there are situations like this—towards the perpetrator as well. As Buddhists we don’t want to get involved with either blaming the victim or condemning the perpetrator, because that’s talking about people, not behaviors. And I think what we need is compassion for everybody involved in this kind of situation. Not a lot of judgment and condemnation and opinions and so on, but to really approach it with compassion.

I think any kind of abuse situation—because there are many situations that happen—all of them need to be approached with compassion for all the people involved.

Having said that, one of the first things people say to me is, “How could this have happened? This is a very well-respected, very well-known lama who’s been around for a long time. International organization. So how could such abuse have happened? Or such circumstances have happened?”

They can happen for a number of different factors. I was present in the 1993 meeting when His Holiness Dalai Lama met with Western Buddhist teachers, and that was a time when there were a lot of abuse scandals in the Buddhist community, not just from Tibetans, but Zen, Therevada, so on and so forth. So, asking His Holiness about these things, and one thing he said was that Buddhism is new in the West and so people don’t know what are the qualities to look for in a spiritual mentor. And in fact, they don’t even know that it’s important to look for qualities. We assume that if somebody is called the teacher that they are in fact qualified. But there is no certification board, and in any case, you’re talking about spiritual understanding. How are you going to certify that anyway? People become teachers, His Holiness explained, because other people come to them and say, “Please teach me.” That’s kind of how it happens. There’s no licensing thing. So it’s kind of up to the individual students to check the qualities of different people before they accept those people as their teachers. But with Buddhism being new in the West, people don’t know that.

We could say, well Buddhism has been around in the West maybe 30 years or more shouldn’t people know this? Not necessarily. No. Because people who are coming in new, they’re just coming in new. They don’t know anything about the Dharma. I certainly didn’t know when I started. Even though that was a long time ago.

Things are new, and the newness affects the students. The newness also affects the teachers. The teachers come over here and they’re often alone instead of having a community of other Tibetans around them, which really helps people keep their behavior in check. If they’re often the only person at a Center then they have no other Tibetans around them who know what the proper conduct is, and instead what’s around them are students who are adoring, who love this teacher. The teacher’s very charismatic. Even though charisma is not one of the qualities of a qualified spiritual mentor, for people new in the Dharma charisma speaks loudly, and so the students just adore the teacher, they appreciate the teachings that the teacher gave, and the teacher has nobody else around them who are their friends, who they can talk to if they have difficulties, who—through the presence of other friends like that—keep their behavior in check.

Also, when you have lay teachers—as in this particular case—then you have people who don’t have the monastic precepts. They aren’t bound by those precepts, and also the students don’t expect that. They wouldn’t expect celibacy out of a lay teacher. Although they would out of a monastic teacher.

That’s another way that things can happen, because everything is new, nobody really knows the expectations, aren’t really on line.

Also, you have to look inside the particular teacher. Some people have more or less self-discipline. Some people have more or less teachings. You may have people who are known as teachers who have studied with very great lamas, but if they did that when they were young, then we don’t really know how much…. If they are recognized incarnates and they studied with other lamas when they were young, we don’t know as children how much they absorbed from it. Also, their self-discipline may not be very strong. And it becomes very easy to be influenced when you have all these people around you who think you’re wonderful and, in the case of Tibetan teachers (or foreign teachers, Asian teachers in general, but especially Tibetan), who have this “shangri-la” projection on everything Tibetan. Everything from Tibet is shangri-la, hidden in the mountains, they have all these holy people, so everybody who’s Tibetan must be holy. They must be special.

Tibet is a society like every other society. They happen to have a lot of very realized beings. But that doesn’t mean that everybody who’s Tibetan is a realized being. So you take your debate class and you do the four points between “Tibetan” and “realized being.” And there’s no pervasion that if you’re Tibetan you’re a realized being. And no pervasion that if you’re a realized being you’re Tibetan. You’ve got to check your pervasions there.

Another thing that I think is big is that people are given highest class tantra initiations way too soon. People will disagree with me here. In Ancient India, highest class tantra was very private. The initiations were given to a few people, if you were a practitioner. Nobody else knew. Everything was kept very quiet, very private.

When Buddhism came to Tibet, tantra became very popular, and initiations began to be given quite widely. So that’s already happening in Tibetan society. Then when Buddhism comes here, we of course want the highest teachings, because we’re us, we want the highest teachings, so we want highest class tantra initiation, we want Mahāmudrā teachings, we want Dzogchen teachings, and what we don’t understand is that all these teachings are advanced teachings, and to really understand them you have to have a very solid foundation on the basics. And this is the way things were set out in ancient India, and that’s why tantra was so private and not very widespread.

The attitude now in the Tibetan community, and amongst most of the lamas, is that if you had to wait until you were fully qualified to take highest class tantra initiation—in other words, you had renunciation of samsara, you had spontaneous bodhicitta, you had at least an inferential realization of emptiness—if you waited until that, then very few people are prepared for that, and so they think it’s very good you plant seeds to be able to meet the tantra in future lives by receiving a tantric initiation right now.

Here I’m talking about highest class tantra specifically, which is a much more complex practice with many more precepts and pledges and commitments, and so on, to it, than the lower class of tantra.

These are given very freely now, especially in the West, for two reasons, I think. Because the Westerners want them…. Not actually in the West. I saw this in southeast Asia also. To a big extent in southeast Asia. People want these initiations. They think that there’s something especially holy, especially exotic, especially profound about these initiations. Especially in southeast Asia what I’ve seen is that the less people understand during the initiation ceremony, the more they think they got a big blessing. If you have a lama, and they’re chanting in Tibetan with a big voice, and ringing a bell, and a drum, and there’s water, and there’s brocade, and there’s long trumpets, and there’s high thrones, and there’s this whole big thing, and you’re told—even though you’re new to the Dharma—this is a once in a lifetime opportunity, you’ve got to take this initiation, it plants so many good seeds on your mindstream. And so there’s pressure, actually, from the students in the Dharma center for everybody to take it.

People, sometimes who are brand new to the Dharma, take these initiations, and then afterwards, they find out that there are commitments to them, and there are precepts and stuff, and they go “What have I done? I can’t even understand the words and the precepts. What’s generation stage? What’s completion stage? I don’t know what any of this means.” And they’re really confused. And so some of them actually give up the commitments. They give up the Dharma because of it.

It seems that unless—the one saving factor in this—is that if you are present at an initiation but you did not understand that you were taking precepts, you did not understand you were taking the bodhisattva precepts or the tantric precepts, you did not follow the visualizations of the initiation, in those cases then even though your body was present, you may have heard the words, you did not actually receive the initiation, so you don’t have the precepts and commitments entailed. But if you had the idea you’re taking that initiation, and you understood you were taking precepts and so on, then you knew something about what you were getting yourself into and it’s really good to keep those.

I think this whole thing about people getting into tantra too soon, and already you’re visualizing yourself as a deity before you even know conventionally who you are in an ordinary sense. I think much more preparation is actually needed.

It also happens, and excuse me, I say this with all due respect, but when lamas give initiations in foreign countries more people come and more dana is given. So they have more dana to take back to their monasteries and their people in India or Tibet. I remember one time when His Holiness, he was teaching on the Heart Sutra in Mountain View, California, and many people of course came to the teachings. On the last day he gave the Medicine Buddha jenang. They had to open up the field behind the auditorium because more people were coming. And His Holiness said it should not be this way. More people should come for the teachings and fewer for the initiations and jenangs. But again, Buddhism is new, people don’t know, they hear this is something special, and the lamas don’t always stop that. Many of them don’t speak English (or whatever language) so they don’t even know this is going on. And, so, many people come and they wind up with these things way too soon.

Even if somebody is prepared, it’s important for the teacher to explain the commitments before the initiation is given. And to explain what it entails, what you are assuming. Especially with highest class tantra initiations where you talk about samaya, or commitments, it’s important that the students are informed beforehand about these commitments so that they can choose whether they are prepared to keep them or not.

But lots of times that isn’t done, or it’s done as part of the ceremony, and so it doesn’t register with you what’s really going on. They put a vajra on your head and you’re supposed to keep the secrets, and you have no idea what that means. I don’t think it’s always adequately explained to people.

Since a lot of the pain from these abusive circumstances happen in the context of highest yoga tantra, where the misunderstandings occur, that’s one of the fueling factors.

Another factor, I think, is that—at least in the case of sexual abuse by teachers, and it’s usually male teachers and female students—that people are told and they think themselves, “Oh he’s paying attention to me, I’m special.” Or in the context of Tibetan Buddhism, “Oh he must be doing consort practice, so I should feel honored that he thinks I’m a dakini….” Or maybe the lama even says, “Oh you’re like a dakini….” Or, “You’re so beautiful,” or whatever. And the woman, in cases like this where there’s definitely a power differential, she feels very flattered, “he’s paying attention to me, I must be special, I’m getting this special attention, this is a big teaching for me….” And so she doesn’t know to listen to her own internal feeling.

For example, I had one young woman come to me one time, and she said, “So-and so-lama…,” again, very well respected, this one happened to be a monk, “…asked me to come to his room at night and I didn’t feel comfortable going. It seemed rather strange that he would want me to come, single woman alone, to his room at night, so I said no. But now I’m wondering, did I make a mistake? Maybe I should have said yes, because it was an honor that he invited me.” And I said to her, “No, you did not make a mistake. You listened to what was going on in your gut, and you followed that. You did not make a mistake. Do not regret that.” But you could really see how many other people, they would feel “Oh, I’m really making a mistake because this is such an honor.” Women need to feel empowered in all circumstances… And this applies to all…. I mean, last night we were talking about unwise and unkind sexual behavior. All circumstances. You are empowered to say “no” when you don’t want. I think people need to have that courage, regardless of what the situation is.

I think I’d better stop here so we can eat lunch, and then I will continue in the future days. I have a lot of notes of things to cover.

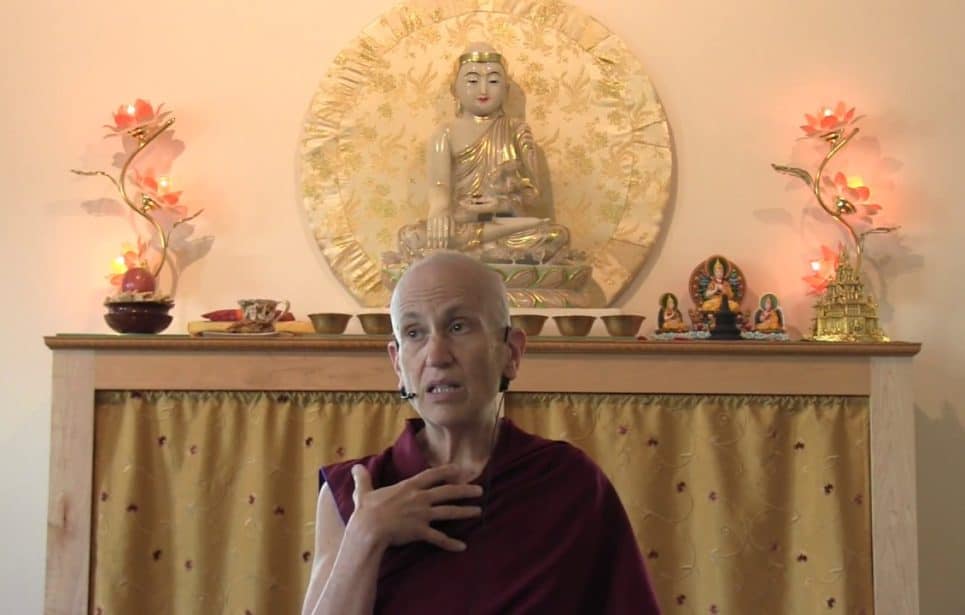

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.