On perfectionism

- Examining our idea of perfection

- Considering if perfection is possible

- How ideas of perfection, for ourselves and others, can be confining

- The problem with perfectionism

I thought today to talk about perfectionism. Since nobody here suffers from that problem, you can all have a nice rest during the talk. But I think actually this is a big problem for many people. And I’ve certainly noticed it in myself. We have an idea of what perfection is and of course, our idea is only an idea but we don’t realize it’s only an idea and we think it’s reality or it should be reality. In order words, everybody should be perfect, and especially as Buddhists. We finally found the way so we should now be perfect; our Dharma friends should be perfect; our teachers should be perfect. And what does perfection mean? It means everyone does what we want them to do when we want them to do it. That’s what perfection means, doesn’t it? This is a really interesting exercise. Maybe we should do this in the upcoming course: have everybody write down your idea of what perfection means for yourself and then what perfection means for somebody else in the group. And what perfection means for somebody in your life that you are very close to and what perfection means for our president. And it would be very interesting to discuss these and see our different notions of the specific qualities someone needs to have or not have in order to be perfect. And I think doing this would really show us how our idea of perfection is simply that, our idea. That’s one part of the equation.

The second part of the equation is, is such perfection possible? Is it a functioning thing or is it a non-existent? Ok, so what is it? Is perfection possible? If we met the Buddha, if you thought of who the Buddha was, how he lived 2500 years ago, would you think the Buddha was perfect or would you have some ways that the Buddha could improve his lifestyle? Like why should he wander around in all these villages, going from door to door getting food? He should do it differently. Or why did the Buddha set up the robes like this? I mean really, they are so impractical. We should have both sleeves covered or both sleeves uncovered. We should have a winter set and a summer set. And pockets, yes and definitely zippers and buttons. Why did the Buddha, really? Couldn’t he improve?

It would be very interesting to go through and really look at how we have so many ideas about how everybody could improve and how likely is it that people are going to follow our ideas. What are our ideas of perfectionism for different groups of people? Another question: why do we have the right to dictate perfectionism? We don’t want to answer that question, but it’s a good question to think about. And third, if the Buddha appeared before us, would we think he was perfect or would we want him to change? What about perfection for our self? Does that lead us to be extremely hard on ourselves, extremely judgmental? How does perfectionism affect our relationships with others when we expect them to be perfect and remember perfect is that they do what we want them to do when we want them to do it.

What I noticed in my own mind is my ideas of perfection both for myself and for other people, give both of us very little space to move. My ideas of perfection are like this. And somebody either falls in them or they fall out of them. And they are not allowed to be a developing human being. They’ve got to be perfect, after all. So to be perfect you can’t be developing, you have to already have attained it. We judge other people that way and also we judge ourselves that way. In order for me to do x, y, z, I’ve got to be perfect at dah, dah… We have this a lot when people come and they are exploring monastic life. I’ve got to have overcome this problem and this problem and this problem and keep all the precepts 100% perfectly before I am capable of ordaining. Of course, if you had all of that perfect, you probably wouldn’t need ordination because you would already be a Buddha. But we hold ourselves to these incredibly high standards as if we really should be superman somewhere or superwoman. So this becomes a big problem in our practice because the standard of perfectionism is very good friends with the judgmental, critical mind. Because we have the standard, we don’t fit into it so we judge and criticize ourselves. Our friends don’t fit into it, we judge and criticize them. Our family doesn’t fit into it, judge and criticize. Even the Buddha, even you look at Chenrezig. Why is he standing with his feet like this? He’s not standing like that. His feet are like this. Then, why did the painter paint him with his feet like this? It looks so uncomfortable. Tara’s shade of green. We have a lot of opinions about the perfect shade of Tara’s green and it’s just not right. I think it should be emerald green. They say blue-green. I don’t like that. Emerald green. Very interesting to watch these kinds of things in our mind and how we box ourselves in, how we box everybody else into these conceptually invented characteristics that we attribute to perfectionism.

And then also another thing to ask ourselves is what problems does this perfectionist attitude bring us? How does it influence our ability to practice? How does it influence our relationships with other people? How does it influence how we live our lives? Does it make us open-minded or close-minded? Tolerant or intolerant? And if we are going to dismantle, do we want to dismantle perfectionism? And if so, does that mean we have absolutely no standards? That can’t be right. But you see we’re extremists, either you have this perfectionist standard or you have nothing. Middle way, folks. There are standards, but there has to be some flexibility. There has to be something that we are working towards, not something that we already have, because we are Buddhist practitioners, not buddhas. Can we see the world through the eyes of Buddhist practitioners? And how can we change our conceptual framework and what happens to our mood when we drop this perfectionist tendency? What happens to our relationships with others? What happens to our refuge when we have a more realistic view of who everybody is?

How does perfectionism relate to consideration for others? In the sense of, what do you mean? If we have social norms about people being polite or impolite or doing things in one way or another and those things aren’t met. It’s amazing how surprised we are when that happens. Sometimes we think well and that becomes high expectations, unrealistic expectations. And certainly, whether it’s somebody that we hold in high regard or we don’t, we have certain expectations of certain politeness or civility. Of course, our expectations are our expectations. Nobody else signed on to them. They seem like they are general societal expectations, but I bet if we discuss them, we’d find out that even in general societal expectations, we all have slightly different ones. Also, even if we come up with common social expectations, why are we surprised when sentient beings who have afflictions in their mind, don’t keep them? Why are we surprised when life happens and people can’t keep their promises simply because the circumstance changed, not even because of an afflicted mind, but the external circumstance changed?

The rigidity of the perfectionist mind can’t adapt to any other possibility than what it thinks. And there’s a whole lot of shoulds in there. She should, she shouldn’t. He should, he shouldn’t. So-and-so’s supposed to, they ought to. They ought not to, they are not supposed to. There’s a lot of that kind of phrasing in our mind that we may not even be aware of. I should dah, dah, dah… I shouldn’t dah, dah, dah… So much and very tight, very rigid. And then when we say, “let’s loosen it,” then we go to the other extreme and oh then it’s a free-for-all. No, we’ve got to have some discriminating wisdom in there. Discriminating wisdom is quite important. But within discriminating wisdom, there is the possibility for circumstances to change, for people who have afflictions to follow their afflictions.

There’s room for differences of preference, differences of opinions and a lot of dialogue. And an acceptance that we are all different because if I look, for example, at what perfection means to me in regards to certain people, it’s really unrealistic and there’s no way that they’re going to have those characteristics because the way they live their life suits them. The way they live their life doesn’t suit me. I like more structure, less structure, more predictability, less predictability, whatever it is. But the choices they make about how to live fits them. An example I always use is one of my teachers runs his life by mos, Tibetan divinations. It works perfectly for him. It doesn’t work for me. But that doesn’t mean that I need to criticize and say, “Why is he doing this? He shouldn’t do that and he should do it the other way.” Because that’s simply a personal preference and it works for somebody else. So, why do I have to get involved in judging?

The way we are often trained in the working world is you have to perform two grades above your current pay grade, otherwise you won’t get promoted. And then you come into Dharma life with that same thing and it just doesn’t work. It doesn’t fit. And even in regular life, what’s wrong with working according to your pay grade? Fear, fear of failure. I’m going to fail. I won’t be promoted. People will think negatively. I won’t have a good reputation. So, I’ve always got to excel. This is qualification for our High Achiever’s Neurotic Association. If you want to enroll, I’m the president, she’s the secretary. You’re vice president. So, you can write to the secretary because she’s got to do it right and see who’s qualified and not qualified.

What does it mean? “I want to be perfect.” What does that mean? “So-and-so should be perfect.” What does that mean? It’s again this whole thing of checking our underlying assumptions that we go through life not even realizing we have and yet they bring us so many problems.

Venerable gave a follow-up talk to this talk here: The pitfalls of perfectionism.

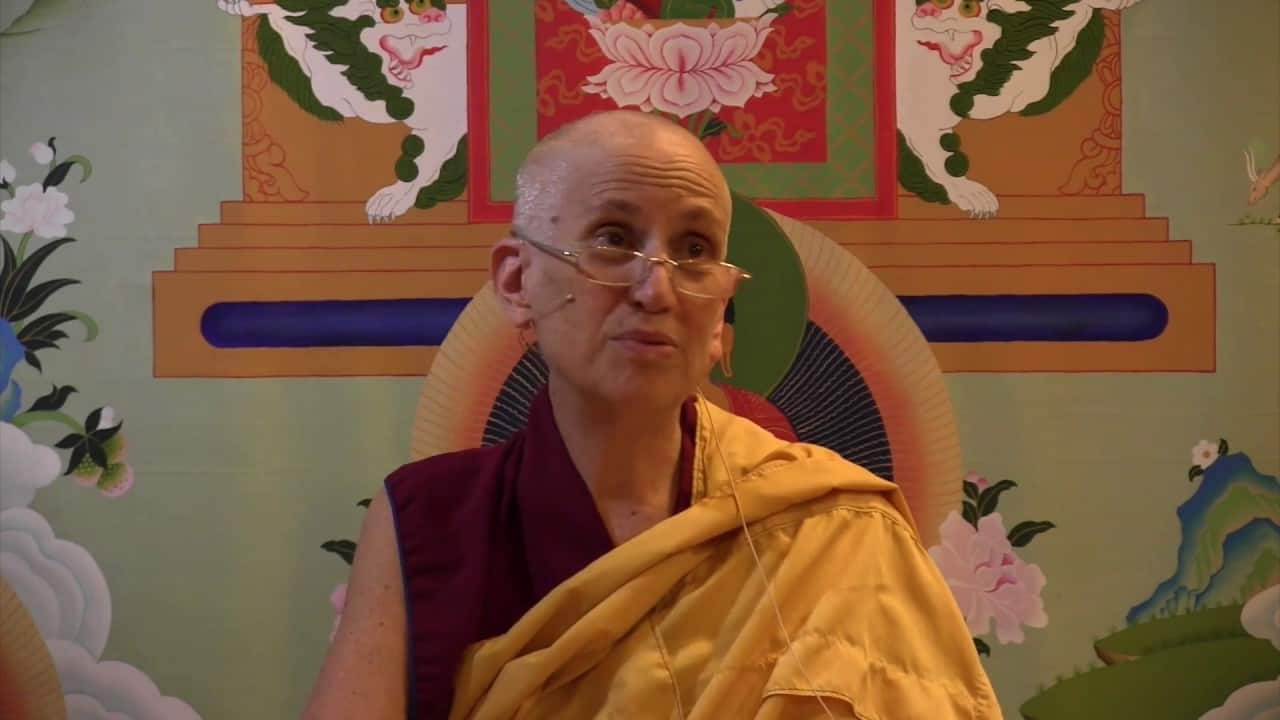

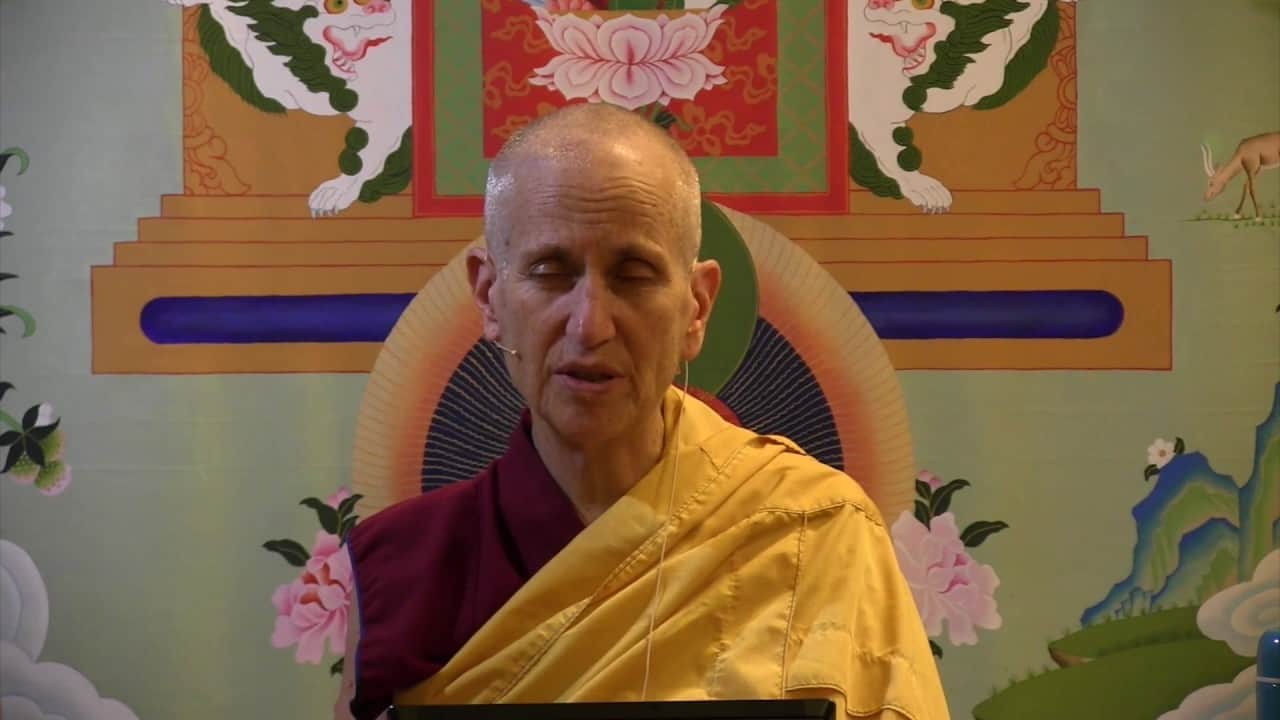

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.