Overview of the stages of the path

The final teaching from the series of teachings on The Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience, a lamrim text by Panchen Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, the first Panchen Lama.

- The relationship of tantra and sutra practices

- Dedication verse

- The three capacity beings—an overview of the whole lamrim

- Each capacity has a certain motivation

- There are meditations to generate the motivation and meditations to actualize the goal of the motivation

- The purpose of cycling through the lamrim meditations

- The benefit of knowing the lamrim outline and doing daily glance meditations or lamrim recitations

Easy Path 60: Overview of the lamrim (download)

Good evening everybody. We’ll start out with our breathing meditation and the practice as usual. Then we’ll have the teaching, Q & A, and this will be the last teaching on the Easy Path. We’re going to finish it today after 60 lessons—something like that.

Tonight will be the last time that I’m leading the practice. I think after 60 times you should know what you’re doing. If you can’t remember the visualization, go back to the very beginning classes and review what you’re supposed to visualize, what you’re supposed to think during each of the prayers.

Also in the Pearl of Wisdom Book 1, the blue prayer book, it has the long version of this. And there, everything you are supposed to think and so on is included. It’s very important to actually meditate when you are doing this and not just do the recitations.

You have to learn how to visualize, what to think, and then do it as you’re saying the words without having me or somebody else guide you. But if there is a group in Singapore, Mexico, or Spokane wherever: If you want to do the practice together and take turns leading it, that could be very good because then everybody has a chance to lead it and get some experience doing that.

Preliminary recitations, meditation, and motivation

Let’s start with some silence. Watch the breath for a minute or two. Let the mind settle.

Then in the space in front imagine the Buddha made of light surrounded by all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas; and yourself surrounded by all the sentient beings.

Refuge

Namo Gurubhya.

Namo Buddhaya.

Namo Dharmaya.

Namo Sanghaya. (3x)

Refuge and Bodhicitta

I take refuge until I have awakened in the Buddhas, the Dharma and the Sangha. By the merit I create by engaging in generosity and the other far-reaching practices, may I attain Buddhahood in order to benefit all sentient beings. (3x)

The Four Immeasurables

May all sentient beings have happiness and its causes.

May all sentient beings be free of suffering and its causes.

May all sentient beings not be separated from sorrowless bliss.

May all sentient beings abide in equanimity, free of bias, attachment and anger.

Seven-Limb Prayer

Reverently I prostrate with my body, speech and mind,

And present clouds of every type of offering, actual and mentally transformed.

I confess all my destructive actions accumulated since beginningless time,

And rejoice in the virtues of all holy and ordinary beings.Please remain until cyclic existence ends,

And turn the wheel of Dharma for sentient beings.

I dedicate all the virtues of myself and others to the great awakening.

Mandala Offering

This ground, anointed with perfume, flowers strewn,

Mount Meru, four lands, sun and moon,

Imagined as a Buddha land and offered to you.

May all beings enjoy this pure land.The objects of attachment, aversion and ignorance – friends, enemies and strangers, my body, wealth and enjoyments – I offer these without any sense of loss. Please accept them with pleasure, and inspire me and others to be free from the three poisonous attitudes.

Idam guru ratna mandala kam nirya tayami

Mandala Offering to Request Teachings

Venerable holy gurus, in the space of your truth body, from billowing clouds of your wisdom and love, let fall the rain of the profound and extensive Dharma in whatever form is suitable for subduing sentient beings.

Shakyamuni Buddha’s Mantra

Tayata om muni muni maha muniye soha (7x)

Then you make your own motivation.

We are listening to teachings in order to make life meaningful. We make our life meaningful by progressing along the path so that we can be of greater and greater benefit to sentient beings—and especially by becoming a fully awakened one because Buddhas have no impediment from their own side to be of benefit to others.

Perfection of wisdom: (continued)

Outline: The way to meditate once non-composite phenomena’s lack of true nature is established

Last time we talked about time, didn’t we? To continue, the text says,

In brief, on the one hand there is space-like absorption one-pointedly focused on the ascertainment that all samsaric and non-samsaric phenomena – the “I,” the aggregates, mountains, fences, houses, etc.—do not have even a particle’s worth of self-produced existence that is not a designation by conception.

We’re talking about the perfection of wisdom. There’s the space like absorption where we’re focused non-dually on emptiness. Non-dually meaning there is no appearance of subject and object. There’s no appearance of inherently existent things, no appearance of conventionalities. The mind is knowing its own nature.

You are seeing the emptiness not just of the mind or the self but of all phenomena. So whether the phenomena are in samsara produced by afflictions and karma, or whether they’re phenomena of nirvana produced by pure causes, it doesn’t matter. They’re all empty of inherent existence. It’s not that samsaric things are empty but when you get to enlightenment things are all solid and concrete and truly existent. No, it’s not like that.

Actually sometimes you hear them speak about the equality of samsara and nirvana. It doesn’t mean on the conventional level samsara and nirvana are the same. That’s ridiculous! What it means is: Looking at their ultimate nature samsara and nirvana are both empty of true existence. That’s how they’re equal—they’re both empty. So don’t reify pure phenomena that are produced by bodhicitta or uncontaminated karma and so on.

On the one hand, there’s the space-like meditation where you’re focusing single-pointedly; and you see that things don’t have even an atom of self-existence—as if self-existence were material. But it’s not. What it means: There’s not even one single bit of self-existence; and that everything is designated by conception.

On the other hand, there is the ensuing illusion-like [concentration] that subsequently understands that all that appears [inherently existent] and arises from a collection of causes and conditions does not exist inherently and is therefore by nature false.

So on one hand, there’s the meditative equipoise directly realizing emptiness. On the other hand, there’s the post-meditation time. It’s called subsequent attainment when you get up and you’re walking around and you’re doing other things—or maybe you’re meditating on other kinds of topics: bodhicitta or generosity. Or you’re doing actions of generosity. In other words, you’re not in meditative equipoise on emptiness. During that time things appear to you, but they appear inherently existent even though they aren’t. Because of having seen the emptiness of inherent existence, when things later appear inherently existent, you realize that’s a false appearance—that things do not exist as they appear to. In that respect they are like illusions. They are not illusions.

There is a big difference between being an illusion and being like an illusion. This is because the object of the illusion isn’t there; but things being like illusions is that they appear one way but they exist in another. So things appear truly existent, but they don’t exist that way. Things instead are dependent. They are dependent on causes and conditions, on parts, on being labelled by term and concept.

You have these two things. In meditation: directly perceiving no inherent existence. Out of meditation: still having the appearance of inherent existence but realizing it’s false; and that things exist, but they exist like illusions. That’s when you’re on the bodhisattva stage.

When you actually become a Buddha, then you can perceive the two truths simultaneously. There’s not this kind of contradictory appearance between meditative equipoise and subsequent attainment time. Buddhas can see that things exist dependently and at the same time see that they’re empty of inherent existence. They can see the conventional things, and at the same time see their emptiness. Until you are a Buddha you can’t do that.

Insight is defined as the absorption associated with the bliss of mental and physical pliancy induced by analysis through training well in these two yogas.

Insight is vipaśyanā. It’s the absorption that’s associated with the bliss of mental and physical pliancy, so you have serenity at least—maybe even one of the dhyānas. Here, if you are doing analysis, when you meditate on emptiness it interferes with your concentration—because you’re analyzing. When you’re doing one pointed concentration you usually don’t analyze because the analysis interrupts your concentration. Usually if you have concentration, you can’t analyze; if you’re analyzing, your concentration is interrupted.

When you have a real insight, which is also the union of serenity and insight, you have the ability to stay single-pointedly on the object with the physical and mental pliancy. But the pliancy instead of being induced by single-pointedness (a stabilizing meditation), is induced by the analysis itself. So after that then analysis and single-pointedness don’t intefere with each other.

Outline: The way to conclude is as before.

Then the next outline is, “the way to conclude (the meditation) is as before” with your dedication. And, “Between meditation sessions, as before, read canonical and exegetic works that explain the system of insight and so forth.”—so having trained your mind in the common path in this way.

Wait a minute I skipped one little bit here. I skipped a paragraph so let’s go back a little bit.

Outline: The way to meditate once non-composite phenomena’s lack of true nature is established (continued)

What I just explained about serenity and insight: “The way to meditate once non-composite phenomena’s lack of true nature is established.” So here it says, “Take space as an example.” There are two kinds of space. Here we’re talking about the unconditioned space—the space that is the mere absence of obstructability and tangibility; the mere absence of form. “As space has many parts, directional and inter-directional, analyze whether it is one with them or distinct from them. Once you have generated the ascertainment of non-inherent existence, meditate on it as before.”

It’s the same kind of analysis when you’re looking at space. It’s an absence of obstructability. But it still has parts because you have the space in the east and the space in the west. You have the space where the table is and the space where the chair is. There are parts to space even though that unconditioned space is an absence and not some kind of positive phenomena. Again, you can analyze whether space as a whole is one with or totally separate from its parts—the different places where there’s space. And again you can’t find it as either one with or separate from. This means that space is dependent. It’s not inherently existent. It’s permanent, but it’s also dependent. It’s not dependent on causes and conditions, only conditioned phenomena are dependent on causes and conditions. But space is definitely dependent on parts, and it’s dependent on being conceived and named.

Then we have that bit about serenity and insight; and the way to conclude that part about “read canonical and exegetic works.”

Concluding verses

Then it says, “Having trained your mind in the common path in this way…” The common path refers to what we’ve covered so far. It’s called the common path because it’s common to sutra and tantra. When they talk about sutra and tantra, or sutrayana and tantrayana: Sutrayana is the vehicle that has been taught in the sutras; and tantrayana is the approach taken in the tantras. All that we’ve covered before are common to those two.

This is something that’s very important for people who want to practice tantra to realize—that tantra is not a separate vehicle unrelated to sutra. It has all this material in common with sutra. It’s called the common path. So you have to master this material before your tantric practices can bring any result. Otherwise you’re just chanting this and that and visualizing this and that, but nothing is changing in your mind.

Having trained your mind in the common path in this way, it is absolutely necessary to enter the vajrayana, for thanks to that path you will easily complete the [two] collections without having to take three countless eons to do so. Moreover, having received an experiential explanation on the way to rely on a spiritual mentor up to serenity and insight, meditate daily in four sessions, or at minimum one, and gain a transformational experience of the stages of the path. This is the best method to take full advantage of your life with freedom and fortune.

He says it’s absolutely necessary to enter the vajrayana when you are prepared, because the vajrayana can help you become a Buddha more quickly than the sutra path can. This is because in the sutra path we have the two collections of wisdom and merit, and they’re collected separately at different times. In the tantric path, you can fulfill the collections of merit and wisdom by doing one meditation. You can fulfil them at the same time. So it’s a different kind of training. But for that training to be really effective you really have to have renunciation, and bodhicitta, and wisdom understanding emptiness.

If you haven’t realized those things, then at least you have to have some good understanding of them. If you don’t have any really good understanding of them then tantra doesn’t mean very much to you. After a while you think “What’s the use of this?” and you then give up the pledges and commitments. That’s not very good. No hurry to rush into tantra; it’s better to establish a very solid basis for your practice.

So in tantra instead of taking three countless great eons to accumulate merit and wisdom, if you are properly prepared you can do it in this very lifetime—or in the bardos. But you have to have practiced for a long time before that.

Then he’s saying, “having received an experiential explanation on the way to rely on a spiritual mentor up to serenity and insight…” Having experiential explanation where you hear the teachings, and then you go away, you meditate, and you gain some experience of them. Then in that kind of way of studying and learning the Dharma, you should do four meditation sessions a day (or at least one) on the lamrim to gain that transformational experience of the stages of the path. This is the best way to take full advantage of your life.

I don’t know about you but before I met Buddhism when I was a kid I was always wondering, “What’s the meaning of my life? Why am I here? What the purpose?” Here he is telling us—very plain and clear. You do it by meditating on the lamrim and gaining experience of that. You can see as you learn the lamrim and all these teachings, you can see how your mind changes—you’re not the same way as you were before. It’s impossible to remain the same way. Your afflictions automatically get subdued when you really practice the lamrim.

Dedication verse

Then he has a dedication verse.

The thought of the incomparable master of the cane sugar clan [King Shakya clan]

Elucidated by the glorious and excellent Dipamkara [Atisha] and his spiritual heirs,

And the second Buddha, Je Losang (Drakpa) [Je Tsongkhapa]

Is presented here concisely in the order for practice,

As a method for fortunate ones to travel to liberation,…

This is why he put this together. It’s not because he was bored and had nothing to do. It’s not because he wanted to be famous. It’s not because he made up this path. He’s explaining what was taught by the Buddha that was handed down through Atisha and Je Tsongkhapa to him.

Composed by the one known as Chokyi Gyaltsen.

By its virtue may I and other sentient beings

Complete the practices of the three kinds of beings.

Three kinds of beings means/should be three capacities of beings—the initial, the middle, and the great capacity or vast capacity (which I’ll go into in a minute).

Then it says,

I, the Dharma teacher Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen, taught a practical exposition of these stages of the path, the Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience, based on my notes, to the large and complete assembly of monks [at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery] during a summer retreat. [They were doing varsa when he taught this.] Notes were taken at the time, which I was shown and corrected. May the ensuing work be a victory banner for the precious, never-declining teaching!

It was translated into English by Rosemary Patton under the guidance of Venerable Dagpo Rinpoche. Rosemary is, I think, an American who has lived in France for many years. She is one of Dagpo Rinpoche’s close disciples.

Overview of the stages to full awakening (lamrim)

Now I want to go back to this reference that he made about the three capacity beings. This will be an overview of the whole lamrim. If you can, remember this; take notes on it and remember it. It will help you tremendously to know how all the meditations of the path fit together. There’s also in a chart I think in Taming the Mind [book by Venerable Chodron]. You can check.

What we do [in the lamrim] is we talk about the three capacities of beings: Each capacity has beings that have a particular motivation. There are certain meditations they do in order to generate that motivation; and then there are certain meditations they do after generating that motivation in order to actualize the meaning of that motivation. If you remember these you can see how all different aspects of the path fit together for one person’s practice. Then you don’t get confused when you hear different teachings from different teachers and all you’re able to put it together into one person’s practice. That one person, that being, is yourself.

Three levels of motivation and three capacities of beings

The three motivations: The initial capacity being is motivated to attain upper rebirth, a high rebirth as a human being or a god. The middle capacity being ups it a little bit and is motivated to attain liberation or nirvana—arhatship, i.e., freedom from the afflictive obscurations. The high capacity being has upped it some more and their motivation is to attain full Buddhahood for the benefit of sentient beings. You can see how those three motivations build on one another: How they go from initial to medium to advanced. To cultivate each motivation you don’t just sit there and repeat the motivation to yourself. You have to do the different meditations that will make that motivation arise in your mind.

I. Initial level motivation and initial level being

For the initial type of person to generate the motivation to want to have a good rebirth, they’ve already meditated on relying on the spiritual mentor and precious human life. They’ve done that before. But the specific meditations they do to generate that motivation [for good rebirth] is they meditate on death and impermanence. When you think about your death and that everything you’re attached to is impermanent, then—being attached to only the happiness of this life; being so involved in the eight worldly concerns—you’re beginning to see that all of that is useless when you meditate on death and impermanence. Then you think, “After death I’m going to be born according to my karma, whatever karma ripens.” And you realize. “I have a whole lot of negative karma so there is a danger of being born in a lower rebirth as a hell being, a hungry ghost or an animal.” You become quite concerned.

You realize, “I have this precious human life but it’s not going to last forever. I spend a lot of time in the eight worldly concerns which creates a lot of negative karma. And if that ripens at the time of death, I’ll go to the lower realms.” It’s going to be very difficult to get out of the lower realms once you’re born there.

When you’re thinking like that what does your motivation naturally become? “I want to have a high rebirth, how do I do it? I don’t want to go to the lower realms. I want to have a higher rebirth.” It’s those two meditations on death/impermanence and the lower realms that help you create this motivation.

Actualizing a higher rebirth

If you’re going to avoid lower rebirth and have a higher rebirth then there are two meditations you need to practice. One is going for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Why? It’s because when we realize that there’s danger of being born in the lower realms we realize we need help. We can’t figure it out on our own. We realize that we don’t know the path, we can’t make up the path, that actually we’re in danger and we’re lost and we need help fast. So we go for refuge to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

What’s the first instruction that the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha give us in order to avoid being born in the lower realms? It’s ethical conduct—which means understanding the law of karma (or action) and its effects; and cleaning up our act. That becomes all the meditations associated with karma and its effects.

When we were meditating on refuge then we contemplated the qualities of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. We contemplated the reason for taking refuge. We contemplated the guidelines for taking refuge. Now when their instruction to us is to keep pure ethical conduct and abandon negativities, then we have to understand how karma works. So we study the four principle aspects of karma. We begin to understand what the ten pathways of non-virtue are and what the ten pathways of virtue are. We learn about: the different kind of effects that karma brings; what is considered heavy karma, light karma; how to purify it—all those kinds of meditations. That’s what you begin to do for an initial capacity being.

II. Middle level motivation and middle capacity being

The initial capacity being—they’re already setting up a Dharma practice and have refuge and the five lay precepts. Then after a while they’re ready to advance. The next motivation that they want to generate is the motivation to be from all of samsara (cyclic existence). In order to do that, they have to do the meditations that are going to cause them to have that motivation—because the motivation doesn’t come out of the blue.

To cause us to want to get out of samsara, we meditate on the first two of the four truths of the aryas [the first two of the four noble truths]: True dukkha and true origin of dukkha. Here’s where we really get into looking very clearly at what samsara means. We consider the three kinds of dukkha, the six disadvantages of samsara, the eight difficulties of the human beings. You really get into looking realistically at impermanence and into the filthy and foul aspect of the body. You begin to see samsara is not so great. In fact it’s like a horror house.

When you meditate on the second truth of the aryas [the second noble truth], the origin, then you start examining the origin of samsara. Like, “How is it that I’m here in samsara, getting born again and again?” That’s when you start to really look at: What really is the cause of samsara? What’s the root of samsara? You begin to understand what ignorance is. They talk about self-grasping of the person and self-grasping of phenomena—and how those two kinds of grasping are the root of cyclic existence and how they give rise to the afflictions. Then when the afflictions are present, how we create karma [actions]—some of it non-virtuous, some of it virtuous—but all of it being polluted in the sense that karma was all created under the influence of the self-grasping ignorance. You begin to see that everything created under the influence of self-grasping ignorance is not going to be great.

Certainly upper rebirths are better than lower rebirths. But still as long as you’re bound by ignorance, afflictions, and karma you’re not going to have everlasting happiness. You’re always going to be in danger of falling to the lower realms. Why? This is because cyclic existence (samsara) is so unstable and the self-grasping ignorance is so unpredictable, so it gives rise to afflictions again and again. Our mind becomes overpowered by the afflictions.

Seeing that, then you say, “Okay, a good rebirth was good as a stopgap method, but really, if I care about myself I need to get out of samsara altogether. It’s like I’ve been on a merry-go-round. And I’ve been up on the merry-go-round and down. And I’ve ridden the horses and the donkeys and the dinosaurs and the dragons. It’s time to get off. I’m finished and I don’t want to be on this merry-go-round because it’s not taken me anywhere. And it’s all a bunch of dukkha.”

That helps you develop renunciation—which is renouncing dukkha. You’re not renouncing happiness, you’re renouncing dukkha and developing the aspiration for liberation—the determination to be free.

That’s your motivation.

Meditating on the first two of the four truths [the four noble truths] is the way to generate this motivation. Then to fulfill that motivation and get you out of samsara, as you are now motivated to do, you have to meditate on the last two of the four truths—true cessations and true paths. If you break down the true paths you could break them into the three higher trainings—higher training of ethical conduct, of concentration, of wisdom. You could also break the true paths into the eightfold noble path.

In the eightfold noble path, right view and right intention fall under the higher training of wisdom. Then right action, right speech, and right livelihood fall under the higher training of ethical conduct. Lastly, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration fall under the higher training of concentration. Actually right effort applies to all of them but especially to mindfulness and concentration. You practice those. Also included when we talk about the true paths, that’s where we have the 37 harmonies of awakening. They fall under true path. So that’s where you have the four establishments [foundations] of mindfulness, and the four perfect strivings, and the four miraculous legs, the five forces, five powers, seven enlightenment factors, and then again the eightfold noble path.

That’s where all of those come—under the true path.

By practicing the true path—and especially according to the Prasangika view, eliminating the self-grasping ignorance, self-grasping of phenomena, refuting the inherent existence—then you’re able to attain true cessation. True cessation is another name for nirvana or liberation. Sometimes it’s spoken of as having the freedom from ignorance, anger, and attachment. But what it actually comes down to, what true cessation is? It is the emptiness of the purified mind, so the mind that has been purified of the afflictive obscurations. It’s the emptiness of that mind. Or sometimes we say the purity of that mind. So that’s what nirvana is. That’s how you actualize nirvana.

Here it’s talking about actually actualizing nirvana and attaining arhatship. If you want to enter the bodhisattva path from the beginning, you don’t go all the way through the hearer or solitary realizer path and become an arhat and then become a bodhisattva afterwards. It’s called the path ‘in common with’ a middle level being because the middle level being will be satisfied with attaining liberation. But a bodhisattva won’t. Bodhisattvas are not going to complete all of the true cessations and the true paths at that time. Because if the bodhisattva does then it’s so blissful in nirvana, you spend a long time in nirvana—meanwhile sentient beings are suffering a lot. So the bodhisattva doesn’t complete that part of the path at that time. They complete it when they’re in the advanced part.

III. The advanced motivation and advanced capacity being

The advanced or higher capacity being: you have practiced the medium capacity for some time. You really have a very firm renunciation. Then you start looking around; and seeing that the world is bigger than just me you think, “Well, my own liberation isn’t so important.” So then the motivation that they’re aiming at that time to generate is the bodhicitta aspiration to attain full awakening for the benefit of all beings.

How does that person do that? How do they generate that? There are two ways.

One way is called the seven-point instruction of cause and effect. The second way is called equalizing and exchanging both self and others. They’re both done on the basis of equanimity. So first you meditate on equanimity. Then you can do one or the other of those two ways to develop bodhicitta. (Je Rinpoche [Lama Tsongkhapa] also has a way of combining them into one eleven point method.)

Two methods to generate bodhicitta

If you’re doing the seven-point instruction then after equanimity you reflect on these six causes and one effect.

The first one is all sentient beings have been my mother. Two, they’ve been kind as my mother. Three is wanting to repay the kindness. Four is heart-warming love, seeing sentient beings as loveable. Five is compassion, wanting them to be free of suffering. Six is the great resolve, saying I’m going to get involved and bring that about. Those are the six causes and then the one effect is bodhicitta.

Instead of using that method, you can use the equalizing and exchanging self with others method that was explained in more depth by Shantideva. After equanimity you meditate on equalizing self with others. You contemplate: the disadvantages of self-centeredness, the benefits of cherishing others, then you equalize self and others. Then you do the tonglen meditation and then from that comes bodhicitta.

Those are the meditations you do in order to generate the bodhicitta motivation. Once you’ve generated bodhicitta what are the meditations you do to actualize that? To lead you to the full enlightenment that you’re now motivated to attain? You practice the ten perfections which can be condensed into six perfections and the four ways of gathering disciples.

You have the far-reaching perfection of generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude, joyous effort, meditative stability, and wisdom. And the four ways of gathering disciples: generosity, speaking pleasantly which means giving them teachings, encouraging them and helping them to practice, and then being a good example. So you practice those and those are particularly within the sutrayana path, but even if you’re practicing the vajrayana you do those. And then you enter into the vajrayana path. There are four classes of tantra and it’s recommended that if you start taking initiations you do it with the lowest class of tantra, kriya, first because it’s easier—and you work your way up. That’s the way that you actualize full awakening, to fulfill your bodhicitta motivation.

Do you have an image of this? It would be very good if you draw this because you’ll have your own mental image of it. You also see within this the three principle aspects of the path. So you have the three levels of motivation and the three principle aspects of the path. You can find them very clearly. That really helps you when you receive different kind of teachings to know where they fit in your practice. That way you don’t get confused and you don’t see the teachings as contradictory to each other because you begin to see that somebody on the advance level of the path, they can do this which is something that somebody on the initial level of the path does not have the ability to do yet. Do you see where the pratimoksha vow comes? It’s either on the initial or middle level path. The bodhisattva vow comes on the higher capacity being. And the tantric precepts come at the end with tantrayana. So you begin to see, “Oh, these precepts are given at different times according to your capacity.” That’s why the precepts encourage or discourage different things—because they are applying to the specific things that you’re abandoning and mastering at that level of the practice.

It really helps you to not see things as contradictory. To see it as a whole path that you can practice from beginning to end. And it helps us also look, and when we’re honest, to see exactly where we are on the path. I don’t know about you, but I’m at the initial level. Now while we’re at the initial level being, we still can do the meditations of medium and higher level beings in order to familiarize ourselves with those meditations because the more familiar we are with them, then when we have the ability to actually realize them already there are many imprints in our mind and it will be much easier for us to realize them.

Also when you do all of the meditations through the cycle then you begin to really see how they help each other. That even though the advance level practices are more advanced, you get some understanding of them and that inspires you. Although you’re personally an initial level, to appreciate your precious human life and to not want to get completely overwhelmed by the eight worldly concerns—because you can begin to see, “Wow, I have the potential to master these qualities of the high capacity being. And those are really wonderful. So I don’t really want to mess around with the eight worldly concerns anymore.”

As you cycle through all of these meditations they all kind of help each other. For example, when you meditate on death and impermanence and you see, “Wow, I’m going to die, and I don’t know when, and I don’t know how much time I have. And what’s important to me is practicing the Dharma. But I’m not going to practice just the initial level practice. I want to really put some seeds on the higher level practices in my mindstream; and even some time when I’m okay with it, the seeds of tantra—so that I have some familiarity with all of these things.” Your meditation on precious human life and on impermanence and death will inspire you to want to attain real renunciation and real bodhicitta. Meditating on the middle level path will inspire you have a precious human life or a good rebirth next time round. Because you see that if you’re going to get out of samsara, the motivation of the middle level being, you have to have a series of good rebirths that act as the basis to do it.

When you meditate on the meditations of the middle level being—the dukkha of samsara, the origin of the dukkha, and so on, you meditate on that in terms of yourself. As you begin to see those in terms of yourself, then you also say, “Well, everyone else is subject to the same thing.” So that inspires you to want to meditate on bodhicitta. When you do these, you see that they all inspire you to do the others. You really want to keep some familiarity with them even though you may put more emphasis at the level of the path where you presently are.

But when you’re at the initial level and the medium level it’s called the practice in common with the initial level being, the practice in common with the middle level being. It says “in common with” because you are not only that level being. You are already from the get-go putting imprints of bodhicitta in your mind. So you’re just practicing in common with those beings. You’re not practicing their actual path and being satisfied with getting a good rebirth for example, or getting out of samsara for example.

You will see there are some people that really, the way they think they’re definitely initial level beings. They don’t go any further than that. They’re completely, “I need to create merit so that I can have a good life.” And that’s all they think about. They don’t think about liberation. They don’t have that kind of self-confidence and that expansiveness in their mind. They only think about creating the karma for a good rebirth. That’s wonderful, but we’re practicing “in common with” them. We’re not limiting our motivation to just that initial level being’s motivation. We’re going in there with the thought in the back of our mind of, “I want to become a bodhisattva or a Buddha. So I’m practicing in common with this, but I’m going there.”

It’s kind of like being in first grade. You can either be somebody who thinks my goal is to finish first grade and I really can’t think much beyond that. I just want to learn to read and write for first grade level. That’s it. And they focus and do that. That’s different then somebody who says, “Actually, I want to be a rocket scientist or somebody who does incredible work in hospices and completely changes the field. Or I want to be somebody who makes a positive contribution to society through reorganizing the social structure. You have this vast goal, but it’s still the same class with the kid who just wants to master first grade. But you have a very different motivation. You’re still doing the same ABC’s but the way you’re doing them is different because of the vastness of your ultimate aim. That’s why it’s called “in common with.” We have the bodhicitta but we’re meditating on the four noble truths of the aryas.

This is different from somebody who’s an actual middle level being who wants to get out samsara and they’re not thinking about enlightenment or other sentient beings. They’re not horrible but they’re not devoting their life to sentient beings. But they have love and compassion, they’re kind people. They want to get out of samsara—wonderful motivation. But as aspiring bodhisattvas and aspiring Buddhas we’re practicing in common with them. We’re not practicing the middle level path because we don’t want to just attain nirvana. We want to go further.

We practice in common with the initial and middle level; the higher level we practice. There’s no in common with. You just do it because we have from the get-go this broad aspiration.

It’s very good on a daily basis to recite one of the glance meditations that go through all the stages of the path from the beginning to the end—because that way we plant it in our minds. The glance meditations are very short. You have The Foundation of All Good Qualities—one page, a couple of pages depending on what size paper; The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, the 37 Practices of Bodhisattvas, the lamrim prayer at the end of the Lama Chopa. There are many of these prayers. It’s good on a daily basis to recite them because then every day you are putting the seeds of all those realizations into your mind. Even if you’re just reading the prayer that’s talking about overcoming self-centeredness and that’s not the main meditation you’re doing that day—it’s still like, “I’m going to be careful of my self-centeredness today.” It’s going in the mind.

Before we do questions I want to start at the very beginning and just read the beginning verses. That’s a tradition that we have to start the text over again. Just reading a little bit and not finishing which indicates you have to come together again to finish it. It’s The Easy Path to Travel to Omniscience by Panchen Losang Chokyi Gyaltsen.

At the feet of the venerable and holy masters, indivisible from Sakyamuni-Vajradhara,

I pay homage continuously. With your great compassion I pray to you to care for me.The exposition of the stages of the path to awakening, the profound method leading fortunate beings to Buddhahood, has two parts:

How to rely on spiritual mentors, the root of the path

Having relied on them, how to progressively train your mindThe first has two parts:

I.1. How to conduct the actual meditation session

I.2. What to do between meditation sessionsI.1. The first has three parts:

I.1.1. Preliminaries

I.1.2. Actual meditation

I.1.3. ConclusionFor the preliminaries, in a place you find pleasant, sit on a comfortable seat in the eight-point posture or in whatever position is comfortable. Then examine your mind well, and in an especially virtuous state of mind, think:

In the space in front of me, on a precious throne both high and wide, supported by eight great lions, on a seat of a multicolored lotus, moon and sun discs is my kind main spiritual mentor in the form of the Conqueror Sakyamuni. The color of his body is pure gold. On his head is the crown protuberance. He has one face and two hands. The right touches the earth; the left, in meditation posture, holds an alms bowl full of nectar. Elegantly he wears the three saffron-colored monastic robes. His body, made of pure light and adorned with the signs and marks of a buddha, emanates a flood of light. Sitting in vajra posture, he is surrounded by my direct and indirect spiritual mentors, by deities, Buddhas and bodhisattvas, heroes, heroines and an assembly of arya Dharma protectors. In front of him, on exquisite stands are his teachings in the form of books of light. The members of the merit field look upon me with contentment. In turn, at the thought of their compassion and virtue I have great faith in them.

You can see this text was really written for meditation. Right from the beginning there’s your visualization and then the next verse is the motivation for doing the practice. He wrote this really in the hopes that people would meditate on it.

Questions and Answers

Audience: We familiarize ourselves with all these topics. We may not have realized any of them when we die. So what do we meditate on at death?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): If you can meditate on emptiness—fantastic. If you can’t do that, meditate on the taking and giving meditation. If you do meditate on emptiness, motivate beforehand to do it with bodhicitta motivation. If you can’t do bodhicitta or meditation on emptiness, then the best thing to do is take refuge; meditate on your spiritual mentor and the deity as having the same nature—really taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha with strong aspirations never to be separated from the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha from any of your lifetimes. Then you aspire to have a good rebirth or be reborn in the pure land, so you set a strong intention for where you want to be reborn. When we die we’re creatures of habit. If we want to die meditating on any of those things we have to familiarize ourselves with them now. We have to make those kinds of aspirations and dedication prayers now.

It’s not that we go around our life doing whatever, having a good time, and then realize, “I’m going to die soon. I better get some familiarity with these things. We can see already when we’re human beings now we’re healthy, well fed, not actively dying—we can see how hard it is to practice and control our mind right now. Do we think by not practicing during our life and then waiting until we die, then suddenly we’re going to have good concentration and be able to focus on these topics? No! And some people think I’ll chant “Namo Amitofo.” But if you can’t even remember to chant Namo Amitofo when you’re alive; and if you can’t visualize Amitabha when you’re alive; if you don’t know who Amitabha is and what his qualities are; and what the path is to become Amitabha? Then at the time of death are you going to be able to remember to chant Namo Amitofo? Or even you remember it, are you going to have any idea what in the world you’re aiming for? No, you’re going to sit there and be filled with regret and be filled with all the things that you did during your life that you regret having done and you didn’t purify.

We shouldn’t even count on the pure land. It’s like the last ditch practice after having messed around our whole life. Even if you’re going to do that practice you have to have practiced it while you’re alive; and have an understanding of who Amitabha is and what the path to be born there is. So then you think, “Well, if I don’t do that, all my friends and relatives will do so many prayers and practices for me after I die.” They’ll do the chanting—even though I can’t remember. They’ll make offerings. They’ll have pujas arranged for me. That’s good for our friends and relatives. They’ll create a lot of merit from doing that.

But what about our mind? It will send some good vibes our way, but if we haven’t practiced while we are alive, are we even going to recognize those good vibes and that merit that they’re sending our way? Or is our mind going to be overwhelmed by all sorts of other stuff—simply because during our life we made a habit of our mind being totally distracted by all sorts of other stuff.

We can’t just say, “My friends and relatives will do all of this after I die.” It’s good they do that. It’s beneficial that they do that. But for us to reap the benefit of what they’re doing, we have to practice when we’re alive.

People always say, “Well, how can I help my friends and relatives when they’re dying?” I say, “Help them when they’re alive first. Don’t wait until they die.” Help them when they’re alive. Encourage them to be generous. Encourage them to keep good ethical conduct. Teach them the methods so that they can transform how they look at situations and not get so angry.

Encourage them to go to Dharma talks and read Buddhist books. Introduce them to something virtuous that they can put in their mind while they are alive. Help them to create virtuous actions. That’s the best way to help them. Some of our friends and relatives have no interest in this. What do you do? What can you do? Maybe you just then talk about how wonderful the Dalai Lama is because they saw him on TV and know who he is. So you can talk about his qualities and that puts some good imprints in their mind.

Maybe with some people that’s all you can do—and some people may not even want to hear about the Dalai Lama.

Audience: What about people who do a lot of mantras, who don’t study much, but they do a lot of praying and they have great faith and devotion.

VTC: They go on the initial capacity being. Because they have devotion and faith and usually their prayers are for a good rebirth and that’s what they really want. They may have higher aspirations but they don’t understand it really well. But still that’s good that they have higher aspirations. The basic thing is the more you understand the better you can practice. To understand you have to hear teachings and study. But still people sometimes have tremendous faith and practice very good ethical conduct and that’s beautiful. Sometimes their ethical conduct is even better than those who study a lot and think they’re very fantastic because they know a lot of words. This can really make us question whether we who study a lot really have that level of faith and devotion—or, “Am I just puffed up because of what I know. Am I really practicing anything?”

Audience: How much of a feeling do we need to get for each type of meditation—for instance, impermanence and death before we go on to the next meditation?

VTC: Like I said, you need to go through all of them and keep cycling through all of them before you go from one to the next in terms of your emphasis. For precious human life they say that you have to feel like a beggar who just found a jewel. That’s how you have this awareness of how valuable your life is. For death and impermanence, you feel that, “My death is definite, I don’t know when. It could be any time soon. And I need to practice purely in order to be prepared for it.” Basically what you need to have to go on to the next one in terms of experiential teachings is: Everything that you’re saying to yourself as you’re doing those meditations—you have a gut feeling of those.

Audience: Do we need to observe tantric precepts before we do tantric practice?

VTC: No. You only take tantric precepts when you do yoga and highest yoga tantra. And you can’t know the precepts before you take them, so you certainly can’t observe them before you take them. You only take them when you take those levels of initiation. His Holiness the Dalai Lama advises that you get some familiarity with this whole path that we’ve gone through, and you’ve been a Buddhist for at least five years, before you even take the lower level tantric initiations, let alone the higher level ones.

Audience: If you’re an initial level being, why in the world are you meditating on the four ways to gather disciples?

VTC: It doesn’t mean that as an initial level being you’re gathering disciples. It means that you’re familiarizing yourself with the qualities so that you know what the qualities are—so when it’s time to do that you have that in mind.

Audience: What is the purpose of offerings to the Buddhas? How should we feel when we do this?

VTC: There are many purposes. It creates a connection with us and the Buddha—because you visualize the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. You have all these offerings, both physical and mental ones that you create. You might be offering an apple, but you imagine a whole sky full of offerings. So it creates a connection with the Triple Gem [i.e., the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha]. It creates a lot of merit because you’re being generous. It creates the mind that takes delight in giving which is a virtuous state of mind. We should be thinking with a really happy mind because you create all this beauty.

Very simply when you make offerings it makes your mind very happy. Because you’re visualizing all the Buddhas and bodhisattvas in front of you in their pure land and you’re imagining all these beautiful objects. And here you are offering them to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas. You’re creating an image of incredible beauty that makes your mind very inspired and light. If you really make offerings in a special way, you generate bodhicitta beforehand, you contemplate emptiness after you make the offerings, you bring the entire lamrim into the practice of making the offerings. It’s not just going up to the altar and putting some apples and oranges there. It’s much more than that.

Anything else? Okay, let’s dedicate.

[Everyone chants dedication prayers]

Note: Excerpts from Easy Path used with permission: Translated from the Tibetan under Ven. Dagpo Rinpoche’s guidance by Rosemary Patton; published by Edition Guépèle, Chemin de la passerelle, 77250 Veneux-Les-Sablons, France.

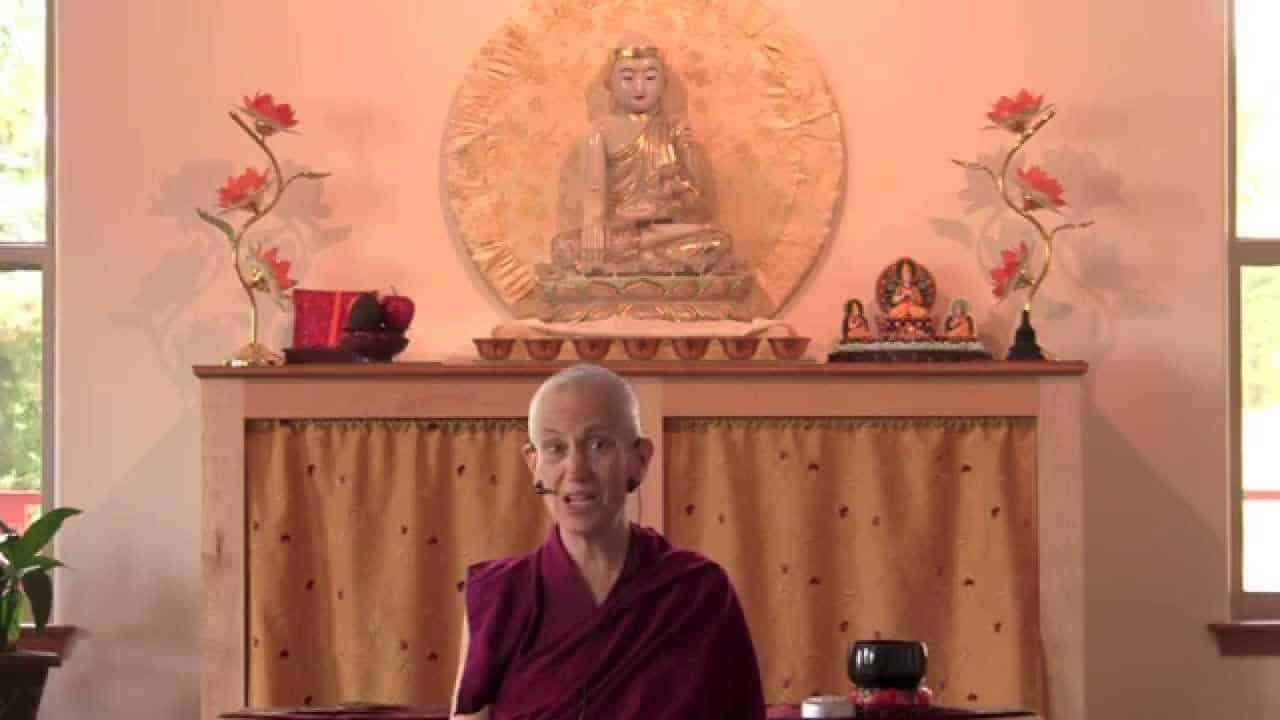

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.