Raising a moral child

Part one of a commentary on the New York Times article "Raising a Moral Child" by Adam Grant.

- Parents are more interested in their children becoming compassionate and helpful than becoming high achievers

- How parents respond to good behavior in their children is important

- Separating the person from the behavior

Raising a moral child (download)

We have another article from the New York Times. A different author. It was called “Raising a Moral Child.” Which I think is quite interesting. Not only for children, but I think for adults, how do you encourage people to be ethical? So again, I’ll read you a little bit and comment on it. So this person says:

What does it take to be a good parent? We know some of the tricks for teaching kids to become high achievers. For example, research suggests that when parents praise effort rather than ability, children develop a stronger work ethic and become more motivated.

Yet although some parents live vicariously through their children’s accomplishments, success is not the No. 1 priority for most parents. We’re much more concerned about our children becoming kind, compassionate and helpful. Surveys reveal that in the United States, parents from European, Asian, Hispanic and African ethnic groups all place far greater importance on caring than achievement. These patterns hold around the world: When people in 50 countries were asked to report their guiding principles in life, the value that mattered most was not achievement, but caring.

Despite the significance that it holds in our lives, teaching children to care about others is no simple task. One study found that parents who valued kindness and compassion frequently failed to raise children who shared those values.

Are some children simply good-natured–or not? For the past decade, I’ve been studying the surprising success of people who frequently help others without any strings attached.

That’s a worthwhile thing to study, I think.

Genetic twin studies suggest that anywhere from a quarter to more than half of our propensity to be giving and caring is inherited.

I’m not sure I buy that.

That leaves a lot of room for nurture, and the evidence on how parents raise kind and compassionate children flies in the face of what many of even the most well-intentioned parents do in praising good behavior, responding to bad behavior, and communicating their values.

By age 2, children experience some moral emotions–feelings triggered by right and wrong. To reinforce caring as the right behavior, research indicates, praise is more effective than rewards. Rewards run the risk of leading children to be kind only when a carrot is offered, whereas praise communicates that sharing is intrinsically worthwhile for its own sake.

So, I think that’s quite interesting. That if you always raise kids–or even adults, with the whole idea of conditioning–and you have your carrot out in front, some material something that people can get, that that runs the risk of people only being kind if they can get something. Whereas praise makes people feel good about themselves because of thinking, “I’m a good person.” And that’s the kind of child you want to raise. And in any setting. Even adults. Even here, too. You want people to be kind and caring not because Buddha said so, not because otherwise you have to do whatever, but because you feel like it’s an intrinsically good thing to do.

But what kind of praise should we give when our children show early signs of generosity?

So there are different kinds of praise.

Many parents believe it’s important to compliment the behavior, not the child–that way, the child learns to repeat the behavior. Indeed, I know one couple who are careful to say, “That was such a helpful thing to do,” instead of, “You’re a helpful person.

So saying, “That was a helpful thing to do” talks about the action. Saying, “You’re a helpful person” talks about the child as a human being.

But is that the right approach? In a clever experiment, some researchers set out to investigate what happens when we commend generous behavior versus generous character. After 7- and 8-year-olds won marbles and donated some to poor children, the experimenter remarked, “Gee, you shared quite a bit.”

The researchers randomly assigned the children to receive different types of praise. For some of the children, they praised the action: “It was good that you gave some of your marbles to those poor children. Yes, that was a nice and helpful thing to do.” For others, they praised the character behind the action: “I guess you’re the kind of person who likes to help others whenever you can. Yes, you are a very nice and helpful person.”

Which one do you think worked better? How many people think the first one? The second one? About half and half.

A couple of weeks later, when faced with more opportunities to give and share, the children were much more generous after their character had been praised than after their actions had been. Praising their character helped them internalize it as part of their identities.

Okay, here I want to pause. Because I can see that, that praising, they internalize it as part of their identities, but I think it’s also important with children, and with adults, that you also state what the action was that they did. Because otherwise so many things transpire, they’re not really sure what it was they did that you’re approving of. So I think it’s very important to say, (for example), “When you cleaned up your room, that was a very nice thing to do and you’re a very considerate person because you know that it makes everybody in the house happy.” Something like that. So I think it’s good if you put in both of them. So you make sure that the person knows that what they did was something that you recognize as valuable. Otherwise, especially with little kids, it’s like, “What did I do?” I think, on the contrary, when you’re trying to discipline kids, that’s when you should really emphasize the action and not the character. And say, “That action was harmful, that action hurt somebody’s feelings.” But usually what parents do is they say, “You’re a bad person. You’re a bad boy. You’re a bad girl.” And that makes the kid feel very bad about themselves and makes them feel like they’re defective inside. When all you’re really trying to do is discourage the particular behavior. So it’s good to consider that. I think negative feedback, don’t talk about the person. Because anyway, we believe that everybody has Buddha nature. So telling somebody they’re a bad person or a good person is really inaccurate. There just talk about the deeds. And it seems like with praise that they’re saying the kids respond better when you talk about their character, but I actually think you have to talk about the behavior, too. So that they know what it was they did.

A couple of weeks later, when faced with more opportunities to give and share, the children were much more generous after their character had been praised than after their actions had been. Praising their character helped them internalize it as part of their identities. The children learned who they were from observing their own actions: I am a helpful person. This dovetails with new research that finds that for moral behaviors, nouns work better than verbs. To get 3- to 6-year-olds to help with a task, rather than inviting them “to help,” it was more effective to encourage them to “be a helper.”

So instead of saying, “Please help me,” say, “Please be a helper.” Interesting

Cheating was cut in half when instead of, “Please don’t cheat,” participants were told, “Please don’t be a cheater.” When our actions become a reflection of our character, we lean more heavily toward the moral and generous choices. Over time it can become part of us.

So how does that apply to us? “Please don’t cheat” versus “please don’t be a cheater.” When you say something to somebody and they say, “I don’t think that’s true,” that sounds very different than saying, “You’re a liar.” Doesn’t it? Somebody says, “You’re a liar,” and that’s, you know… And what’s more affrontive? “You’re lying!” or “You’re a liar.” Which one would strike you. “You’re a liar.” Yeah? So that’s talking about our character. Rather than “you’re lying” is just the behavior. So it’s also showing when we give feedback, we talk about the action. If we have to give negative feedback. Talk about the action because it’s going to be much easier for the other person to understand what we’re saying than if we do something that brands their character.

And when you look at it. You know, when people are very angry at somebody else, do they talk about the actions or do they talk about somebody’s character? They talk about the character, don’t they? And they call people a name. “You’re a jerk. You’re an idiot. You’re this and that.” They call people nouns instead of saying, “You did this, and that action is disturbing to me.” So it’s interesting to look– Also, this can really help us, I think, when we get angry, is instead of just labeling the person as “that person is a liar, that person is a cheat, that person is blah blah blah…” To think of “that person did this behavior.” And I think if we look at the behavior then also the intensity of our anger isn’t so much. What do you think? Where as soon as we say “that person is so–” We sometimes use adjectives, too. “Oh, that person is just ridiculous.” So there is a case of adjectives. But it’s not, “That person is ridiculous, that person can’t be trusted, that person is blah blah blah…” That also is very different than saying “that person did this action.” Because even you’re not using a noun there, you’re using an adjective. You’re branding it as if the whole person were that, rather than discussing a particular action that they did.

So it’s something to look out for in ourselves when we get upset with something. Are we upset with the person or are we upset with the behavior? We usually get upset with the person. But it’s actually the behavior that we should be upset with, isn’t it? It’s not the person. The person has Buddha nature. In another situation the person can act totally differently and they’re our friend and we like them. So it’s always the behavior that’s objectionable. So this mind that, again, creates friend and enemy, which are nouns and categories, really hinders us from forgiving people and accepting apologies and so on. And instead we just give a label which could be a noun or it could be an adjective: can’t trust them, whatever it is. But whenever we do that it actually impedes us from connecting with that person and having an attitude of loving-kindness, or even acceptance or even forgiveness. It’s interesting, isn’t it? To see how we describe things in our mind. And how when we give certain labels we make it much more difficult for ourselves to forgive. And that actually can be very very dangerous because we have–in both our root and auxiliary bodhisattva vows–precepts about accepting others’ apologies. When somebody apologizes and we don’t accept their apology because ‘that person’s a jerk, can’t trust that person’–you know, we’ve described it that way to ourselves–we are breaking our bodhisattava vows by not accepting others’ apologies. So who does that hurt? Us. So very important if we find ourselves resistant to accepting others’ apologies that we really look at our own mind and how we’re describing things to ourselves. Because in fact we’re harming ourselves.

Okay, I’ll just do one more paragraph, then the rest tomorrow.

Praise appears to be particularly influential in the critical periods when children develop a stronger sense of identity. When some researchers praised the character of 5-year-olds, any benefits that may have emerged didn’t have a lasting impact: They may have been too young to internalize moral character as part of a stable sense of self. And by the time children turned 10, the differences between praising character and praising actions vanished: Both were effective. Tying generosity to character appears to matter most around age 8, when children may be starting to crystallize notions of identity.

But I think it plays a role even as adults. If somebody says to you: “You’re a really kind person.” Rather than: “Thank you for doing this or that.” You feel much better about yourself, don’t you? You’re able to develop a better sense of self-esteem that way. So it’s good to remember this when we’re giving people feedback.

[In response to audience] So from Romper Room: “Do be a do be and don’t be a don’t be.” And you remember kids of your generation saying that they decided to be a “do be” rather than a “don’t be.” I guess that’s also what you’re encouraged to do. You’re encouraged to just drive yourself crazy producing things or do be like do be a helper.

Continued in Encouraging ethical behavior

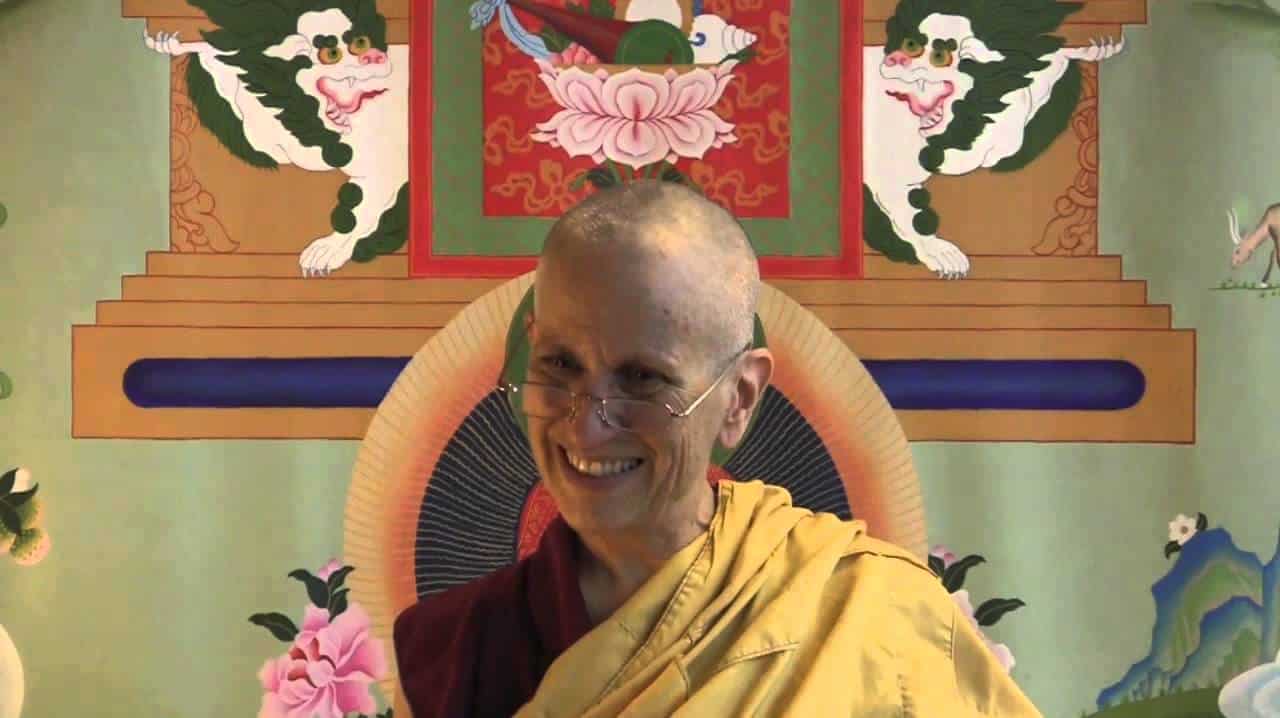

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.