Ordination of buddhist nuns

The ice seems to be broken

For forty years, His Holiness the fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet has stood firmly in support of the revival of the ordination of nuns. In a forward written recently for a booklet on Tibetan nuns,1 H.H. the Dalai Lama explains how, in the eighth century, when the Indian master Śāntarakṣita (725–788) brought the ordination lineage for monks (bhikṣus) to Tibet, he did not bring nuns (bhikṣuṇīs), thus the ordination lineage for nuns could not take root in Tibet.

“It would be good if Tibetan bhikṣus were to agree upon a way in which the Mūlasarvāstivāda bhikṣuṇī ordination could be given… We Tibetans were very fortunate,” the Dalai Lama continues, “that after a decline during the reign of King Langdarma in the ninth century, we were able to restore the bhikṣu lineage which was on the verge of extinction in Tibet. As a result, many people have been able to listen, reflect, and meditate on the Dharma as fully ordained monks, and this has been of great benefit to Tibetan society and sentient beings in general. It is my hope that we may also find a way to establish the bhikṣuṇī saṅgha in the Tibetan community as well.”

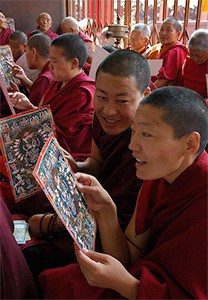

Several important events preceded the Dalai Lama taking this clear position. On April 27, 2011 Lobsang Sangye was elected as the new Prime Minister of the Tibetan Central Administration. On that same day, the German novice nun Kelsang Wangmo became the first woman in the history of Tibetan Buddhism to receive the title of “Rime Geshe.” In May 2012 Phayul, the Tibetan press association in exile, citing official Tibetan government authorities in India, reported, “After years of debate and careful deliberation, Tibetan Buddhist nuns are finally set to receive Geshema degrees (the equivalent of a Ph.D. in Buddhist philosophy).” Today, twenty-seven nuns of five different monasteries are preparing themselves for the Geshe exams, which are scheduled to take place from May 20 to June 3, 2013 in Dharamsala. Previously, it was necessary to study the full Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinayasūtra texts in order to qualify for the Geshe degree. By not having access to full ordination, women were also not allowed to study Vinaya and therefore blocked from obtaining the Geshema degree. Now, full ordination and complete Vinaya studies are no longer required in order to complete the academic training. Although obtaining the Geshema degree is a big step forward, as long as the nuns are not fully ordained and have not studied the Vinaya in its entirety, their Geshema degrees cannot be considered the full equivalent of the Geshe degree, and they cannot perform all of the rituals.

Nevertheless, it is a big step forward. Progress has also been made on the issue of full ordination of nuns. In November 2011 the religious heads of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism decided to form a subcommittee of experts representing all the traditions, “in order to reach a final conclusion as to whether or not there is a method to revive the bhikṣuṇī lineage and to make a clear statement.” This “high-level scholarly committee” consists of ten Geshes—including two representatives from each of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism and two additional scholars representing the nuns. The committee convened on August 6, 2012 in Dharamsala. The opening speech was delivered by Professor Samdhong Rinpoche, the former Prime Minister of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile, himself a monk and the founder of the Central University of Tibetan Studies in Sarnath/Varanasi. In his speech, he summarized the current state of research and suggested questions for the committee to concentrate on.

For more than three months, the monk-scholars met at the Sarah Institute in Dharamsala and worked through all thirteen volumes of the Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, taking note of every place in the texts that referred to nuns and their ordinations. Unlike previous meetings, which only lasted a few days, and did not go beyond presenting contradictory interpretations in the commentaries to the Tibetan texts, priority was now given to the canonical texts themselves.

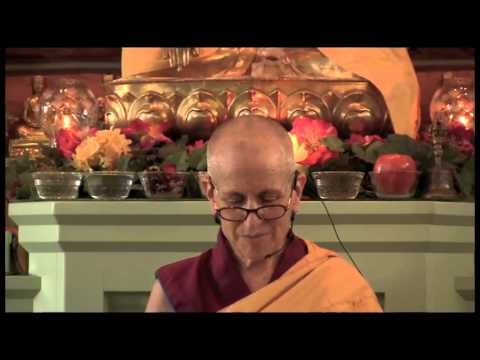

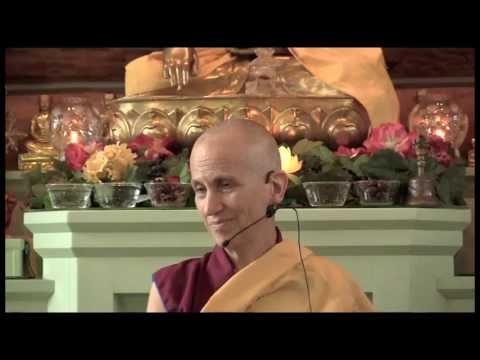

In October 2012, accompanied by Bhikṣuṇī Thubten Chodron, the abbess of Sravasti Abbey (USA), just prior to the finalization of the committee’s 219-page report, I was invited to table my research. Unlike previous meetings, such as an important seminar on the issue in 2006, the atmosphere of this meeting was quite friendly and constructive. The monks were seriously interested in finding the solution and pledged that no references would be withheld.

Also present at this meeting was Geshe Rinchen Ngodup, a great supporter of the ordination of nuns, representing the Tibetan Nuns Project in Dharamsala, together with another Geshe. Although this was the first time that I held an academic talk in Tibetan, which was quite a challenge, my presentation was followed by intensive discussion and a very lively exchange of different references.

The following day, a group of Tibetan nuns joined us at the conference, along with Bhikṣuṇī Tenzin Palmo. Bhikṣuṇī Thubten Chodron discussed what kind of changes to Tibetan Buddhism could be expected if the full ordination for Tibetan nuns were introduced. She also presented the scholarship that suggests the two Chinese monks who helped to restore the Tibetan lineage after the death of Langdarma must have belonged to the Dharmaguptaka, a different lineage from the Tibetan lineage (Mūlasarvāstivāda), yet the monks’ lineage today could only be kept alive by having an ordination ceremony performed by Mūlasarvāstivāda monks supported by Dharmaguptaka monks (in order to fulfill the required number of monks for the ritual).

Bhikṣuṇī Tenzin Palmo spoke mainly about the methods used in recent years to revive the ordination of nuns in the Theravāda tradition in Sri Lanka. Thereafter, the ten monks delivered insights into the topics of their own research, which is expected to be published in the near future and made available to all monks so that they can draw their own conclusions on the issue.

In January 2013 I was invited to speak at the first “International Buddhist Sangha Conference” in Patna about the revival of the ordination of Buddhist nuns. The conference was inaugurated by H.H. the Dalai Lama and the Prime Minister of Bihar. In addition, another fifteen high-level representatives of Buddhist countries in Asia came to Patna, in particular from the Theravāda countries, where similar challenges exist regarding the ordination of nuns. In Sri Lanka, the monastic orders died out in the eleventh/twelfth century and, although the monks’ order was revived, the nuns’ order was not. According to existing records, the Theravāda bhikkhunī order was not transmitted to other Theravāda countries. It was, however, transmitted to China, Vietnam, and Korea. Modern scholars confirm the closeness between the Theravāda Bhikkhunī Pātimokkha in Sri Lanka and the Dharmaguptaka Bhikṣuṇī Prātimokṣa in East Asia, one of the reasons the East Asian bhikṣuṇīs and bhikṣus were called upon to help restore the nuns’ order in modern-day Sri Lanka, together with the Sri Lankan Theravāda bhikkhu sangha. Subsequent ordinations have been carried out by a dual sangha of Sri Lankan Theravāda bhikkhus and the dually ordained Sri Lankan bhikkhunīs. The lineage re-established in Sri Lanka has grown over one decade and bhikkhunīs in this lineage have already participated in ordinations for Theravāda women in other countries, including Thailand and the United States. Thus the bhikkhunī order in the Theravāda tradition is now over one thousand in Sri Lanka, more than fifty in Thailand, Nepal, Indonesia, Singapore, Europe, and North America, and therefore, a few steps ahead of the Tibetan tradition.

The theme of the conference in Patna was the “Role of the Buddhist Saṅgha in the Twenty-first Century.” The issue of the “ordination of nuns” could not be ignored at this conference, not least because just an hour’s drive away, hundreds of women from more than thirty countries had gathered for the thirteenth “Sakyadhita International Buddhist Women’s Conference” in Vaishali, the place where the Buddha is believed to have founded the order of nuns.

The Patna conference was the first time any such conference held a panel on the revival of bhikkhunī ordination, consisting of Bhikkhunī Dhammananda (Thailand), Bhikkhunī Ayya Santini (Indonesia,) and myself (incidentally, the only three fully ordained nuns invited as speakers to the conference). During that panel, three monks from the Theravāda and Mahāyāna traditions bravely expressed themselves positively regarding the issue. Following the panel, during a workshop on the same topic conducted by Bhikkhunī Dhammananda, several Tibetan monks requested information from her and expressed their goodwill for the reintroduction of the ordination of nuns. Thus, the ice seems to be broken, as indicated by more and more monks daring to openly discuss the issue. This is very encouraging.

The idea to initiate an independent research team with the task to reveal all references, without being tasked to make a final decision, seems to be wise, because it allows the researchers to concentrate on the facts without having to fear any criticism from conservative circles if they discover supportive sources in the texts. It is possible that every monk who studied the Vinayasūtra of the Mūlasarvāstivāda together with its Indian and Tibetan commentaries carefully, knows that from a legal point of view the revival of the Mūlasarvāstivāda ordination lineage for nuns is definitely possible. As long as the ordination lineage of monks is alive, the ordination lineage of nuns is latently alive too, and thus it can be revived at any time.

It is clear from the texts that if there are no existing Mūlasarvāstivāda bhikṣuṇīs to revive the order, Mūlasarvāstivāda monks can perform the ordination procedure instead, since the very first nuns at the time of the Buddha were ordained by monks. Gradually, the Buddha gave nuns more responsibilities to lead the ordination procedures themselves. The first stages of the ordination of nuns, i.e. that of a female lay follower (upāsikā), the pre-novice admission to the community (pravrajyā), the stage of a novice nun (śrāmaṇerikā), a female trainee for full ordination (śikṣamāṇā), as well as the approval of the trainee’s readiness for keeping a lifetime vow of chastity (brahmacāryopasthānasaṃvṛti), can be carried out by the nuns alone, while for the full ordination (upasaṃpadā) the order of monks has to be involved.

As the Dalai Lama explained, the reestablishment of his own Gelug ordination lineage was made possible with the help of two Chinese Dharmaguptaka monks. And in many instances through history, monastics of other lineages have made exceptions and stepped in to help revive or revitalize lineages which were in decline. In a similar way, scholars believe that Dharmaguptaka monastics (bhikṣuṇīs) could be invited in, alongside Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda monks, to revive the lineage of nuns, who would then carry the Tibetan lineage. What decides the lineage that the bhikṣuṇīs will hold is the lineage of the participating monks (bhikṣus). Monks in Sri Lanka have demonstrated how to proceed. It is only a question of time for the Tibetan tradition to follow the example and find its own way to proceed. The importance of women’s ordination is greater than ever for the survival of Tibetan Buddhism and Buddhism in the world.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama seems to have an even greater vision, namely, to see that Buddhist monks of all traditions form a council and together—to unanimously or at least with great majority—speak officially in favor of the reintroduction of the full ordination of nuns. While Tibetan nuns, out of fear of being stigmatized, keep their full ordination a secret, nuns from Sri Lanka and Thailand still struggle to have their monastic names and bhikkhunī title entered into their identity papers. In Western countries, where it is very common for Christian nuns to have their monastic names entered into the passports, it is no longer an issue for the Buddhist nuns either. Since Buddhism is relatively new in these countries, the ordination of nuns was established fairly early on, and for newcomers very often is a matter of course today. If necessary, the nuns will travel to countries where bhikṣuṇī ordination is available, but an increasing number is asking to hold the ordination in the respective countries in their local language. Furthermore, practitioners living in the West who come into contact with Buddhism take for granted that as described in the ancient texts, the four groups of followers of the Buddha (catuṣpariṣat)2, including fully ordained men and women, was introduced by the Buddha himself in early times and is a basic principle of Buddhism. By contrast, in the countries where Tibetan and Theravāda Buddhism have developed over many centuries, a gap remains between what the Buddha established and the social realities, which have been allowed to penetrate the Saṅgha.

In summary, the developments in the last year and a half indicate that the Tibetan tradition is close to a breakthrough. If a decision is made as to which of two options are preferred, namely, the ordination by bhikṣus alone or with the assistance of bhikṣuṇīs of other living traditions, then there is no longer any obstacle to the next step, which is to host an international dialogue on the matter, as desired by His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Article appeared in Awakening Buddhist Women, a Sakyadhita: International Association of Buddhist Women blog on May 27, 2013.

For the English draft version see http://bhiksuniordination.org/issue_faqs.html ↩

Tib. ‘khor rnam pa bzhi, see Lhasa Kangyur, ‘Dul ba, 43a6-7 ↩

Venerable Jampa Tsedroen

Jampa Tsedroen (born 1959 in Holzminden, Germany) is a German Bhiksuni. An active teacher, translator, author, and speaker, she is instrumental in campaigning for equal rights for Buddhist nuns. (Bio by Wikipedia)