The four seals of Buddhism

We may wonder: how do we determine whether a particular doctrine of tenet system is Buddhist or not? This is by assessing if it follows the four seals—four basic principles shared by all Buddhists. These four are:

- All conditioned phenomena are transient.

- All polluted phenomena are dukkha—unsatisfactory or in the nature of suffering.

- All phenomena are empty and selfless.

- Nirvana is true peace.

One of the chief factors that cause us difficulty in our lives, and thus in cyclic existence, is that we and everything around us is transient. Whatever we cherish as bringing us happiness—our body, possessions, friends and relatives, reputation and social status, love, honor, and appreciation—all these things arise due to causes and conditions, and thus by their very nature, they change.

When we reflect deeply that by their very nature, things change and nothing can prevent this, we come to understand that whatever enjoyments, relationships, success, and facilities we have at our disposal in cyclic existence do not last long. Although we may have these things now, because they are impermanent by nature, they cannot be totally relied upon or trusted. They do not have the ability to give us long-lasting happiness or to bring real security. Such transient phenomena in cyclic existence are the objects in relation to which we experience suffering. Our suffering, however, is not due to the objects or people we encounter, but is rooted in ignorance, the chief affliction that causes cyclic existence.

Transience, or impermanence, is of two types: gross and subtle. Gross transience refers to an object ceasing to exist. The death of a human being or the breaking of a car are examples of this. Understanding this type of transience is not too difficult. Subtle transience has two meanings. The first is that things change from one subtle moment to the next; they never remain the same. The second is that the subtle transience of phenomena occurs because things arise due to causes and conditions. In other words, the very nature of produced phenomena is that they do not last from one moment to the next. They are produced in the nature of change; their nature is to disintegrate in that very moment. A new cause is not needed to make something disintegrate in the very moment it exists. In other words, it is not the case that things are stable and contact with an external factor makes them change. Rather, their existence is governed by causes and conditions and their very nature is momentary. The causes and conditions that brought that thing into existence are the very causes for its disintegration. This is the meaning of “All conditioned phenomenon are impermanent,” the first of the four seals that make a doctrine Buddhist.

True dukkha, the first noble truth, is comprised of two factors: those in our external environment and those that are the internal world of sentient beings. Not only the feeling aggregate is considered dukkha, so too are the primary minds and mental factors with which it is concomitant and the sense faculties that are causes for these minds. All these have the potential to bring dukkha and so are considered true sufferings.

The external environment is called true suffering because sentient beings’ afflictions and actions influenced its creation and evolution. Since all sentient beings within our world enjoy or use the things within it, they individually, as well as collectively, contributed to its coming into existence. However, once someone has eliminated the afflictions and actions, she is liberated from cyclic existence although she may continue to live in the external world which is a true suffering. In other words, the criterion for being in cyclic existence is not the environment in which a person lives, but her state of mind. All these internal and external factors that are conditioned by afflictions and polluted karma are true dukkha. This is the meaning of the second seal, “All polluted phenomena are dukkha.”

But the story does not stop here because there exists an antidote powerful enough to eradicate these afflictions and karma totally. That is the wisdom realizing the emptiness of inherent existence. Thus the third seal is “All phenomena are empty and selfless.” When selflessness and emptiness are realized directly and non-conceptually and the mind becomes habituated with them through meditation over time, then all afflictions and karma causing rebirth are eliminated. In this way, cyclic existence is ceased and the fourth seal, “Nirvana is peace,” comes about.

The Buddha spoke of the mere “I”—the merely designated self that is in cyclic existence and that goes on to liberation and enlightenment. The distinguishing mark of whether we are in cyclic existence is if the mere I is under the control of afflictions and actions; that is, whether the aggregates in dependence upon which the “I” has been designated is produced by these undesirable causes. If the aggregates are under the control of afflictions and polluted karma, the person who is designated in dependence on them is bound in cyclic existence.

As soon as that person eliminates the afflictions, she no longer creates polluted actions that propel cyclic existence. In that way, cyclic existence ceases, and that person, that mere “I,” is liberated. Gradually, a person can also remove even all obscurations to omniscience, and when this is done, that mere I attains Buddhahood, the state of full enlightenment or non-abiding nirvana, in which the person abides neither in either cyclic existence nor the personal peace that is an arhat’s nirvana.

In summary, the psychophysical aggregates of whatever realm into which we are born in cyclic existence are called the appropriated or the “clung to”1 aggregates, and they result from afflictions and polluted actions. Because they have such inauspicious causes, our body and mind are incapable of bringing us ultimate peace and happiness in the same way that a plant that grew from a poisonous seed will surely make us ill. Identifying the causes and nature of our existence enables us to better understand the various types of unsatisfactory circumstances we experience. By strongly meditating on these faults of cyclic existence and its origins, we will generate an aspiration to be free of them and to attain the state of lasting peace and happiness, nirvana. In describing his own spiritual journey before attaining awakening, the Buddha said:

…before my awakening, while I was still only an unawakened bodhisattva, I too, being myself subject to birth, sought what was also subject to birth. Being myself subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, I sought what was also subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement. Then I considered, thus: “Why being myself subject to birth, do I seek what is also subject to birth? Why, being myself subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement, do I seek what is also subject to aging, sickness, death, sorrow, and defilement? Suppose … I seek the unborn supreme security from bondage, nibbana. Suppose … I seek the unaging, unailing, deathless, sorrowless, and undefiled supreme security from bondage, nibbana.2

While subject to the unsatisfactory circumstances of cyclic existence, we ignorant beings take refuge in other people and things that are also subject to the misery of cyclic existence. What if we were to turn to the Dharma for refuge and seek nirvana instead? The actual Dharma path begins with this aspiration to be free from cyclic existence and to attain nirvana. With it some people seek the personal peace of nirvana, while other people also generate bodhicitta and proceed on the path to supreme awakening.

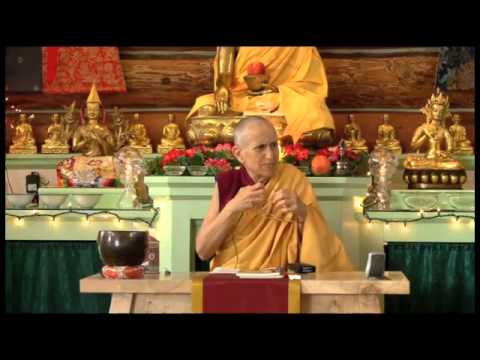

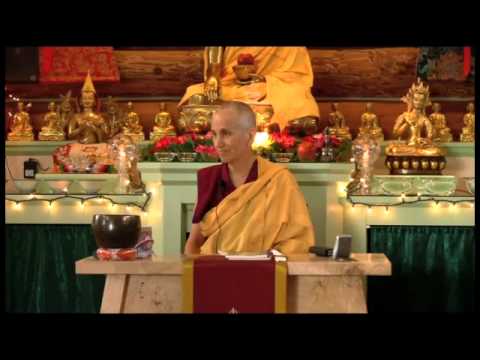

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.