Chocolate frosting and garbage

We hear the great masters say, “Practicing Buddhism is good. It will bring you happiness in this and future lives,” and we think, “Umm… This sounds interesting.” But when we try to do it, sometimes we get confused. There are so many kinds of practice to do. “Should I prostrate? Should I make offerings? Maybe meditation is better? But chanting is easier, perhaps I should do that instead.” We compare our practice to that of others. “My friend just made 100,000 prostrations in one month. But my knees hurt and I can’t do any!” we think with jealousy. Sometimes doubt comes in our mind and we wonder, “Other religions teach about morality, love and compassion. Why should I limit myself to Buddhism?” We go around in circles, and in the process, lose sight of the real meaning of what we are trying to do.

To resolve this, we need to understand what following Buddha’s teachings means. Let’s look beyond clinging to the words. “I’m a Buddhist.” Let’s look beyond the external appearance of being a religious person. What is it that we want from our lives? Isn’t finding some kind of lasting happiness and helping others the essence of what most human beings seek?

One does not have to call him/herself a Buddhist in order to practice the Dharma and receive benefit from it. Interestingly, in Tibetan, there is no word, “Buddhism.” This is noteworthy, for sometimes we get so caught up in the names of religions that we forget their meaning, and busy ourselves defending our religion and criticizing others’. This is a useless venture. In fact the term “Dharma” includes any teaching that, if practiced correctly, leads people to temporal or ultimate happiness. It doesn’t exclude teachings given by other religious leaders, provided that these teachings lead us to the attainment of temporal or ultimate happiness.

Examples are readily available: moral discipline such as abandoning killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct and intoxicants is taught in many other religions, as is love and compassion for others. This is the Dharma, and it is beneficial for us to practice such advice, whether we call ourselves Buddhist or Hindu or Christian or whatever. This is not to say that all religions are the same in every respect, for they aren’t. However, the parts in each of them that lead us to temporal and ultimate happiness should be practiced by everyone, no matter which religion we identify with.

It is extremely important not to get bogged down in words. Sometimes people ask me, “Are you Buddhist, Jewish, Christian, Hindu or Muslim? Are you Mahayana or Theravada? Do you follow Tibetan Buddhism or Chinese Buddhism? Are you Gelu, Kargyu, Sakya or Nyingma?” To this complexity of concepts, I reply, “I am a human being searching for a path to discover truth and happiness and to make my life beneficial for others.” That’s the beginning and end of it. It so happens that I have found a path that suits my inclination and disposition in such and such a religion, and such and such a tradition. However, there is no use in clinging onto the terms, “I am a Buddhist of the Tibetan variety and practice the Gelu tradition.” We already have made enough simple words into concrete concepts. Isn’t this grasping at fixed and limited categories what we are trying to eliminate from our minds? If we cling to such labels in a close-minded way, then we give ourselves no choice but to quarrel with and criticize others who happen to have different labels. There are already enough problems in the world, what is the use of creating more by having bigoted religious views and conceitedly defaming others?

A kind heart is one of the principal things we are trying to develop. If we run around childishly telling others, “I’m this religion, and you’re that religion. But, mine is better,” it is like turning chocolate frosting into garbage: what was delicious becomes useless. Instead, we would be much wiser to look inside ourselves and apply the antidotes to intolerance, pride, and attachment. The true criterion of whether we are a religious or spiritual person is whether we have a kind heart toward others and a wise approach to life. These qualities are internal and cannot be seen with our eyes. They are gained by honestly looking at our own thoughts, words and actions, discriminating which ones to encourage and which ones to abandon, and then engaging in the practices to develop compassion and wisdom in order to transform ourselves.

While we are trying to practice the Dharma, let’s not get entrenched in superficial appearances. There is a story of one Tibetan man who wanted to practice Dharma, so he spent days circumambulating holy relic monuments. Soon his teacher came by and said, “What you’re doing is very nice, but wouldn’t it be better to practice the Dharma?” The man scratched his head in wonder and the next day began to do prostrations. He did hundreds of thousands of prostrations, and when he reported the total to his teacher, his teacher responded, “That’s very nice, but wouldn’t it be better to practice the Dharma?” Puzzled, the man now thought to recite the Buddhist scriptures aloud. But when his teacher came by, he again commented, “Very good, but wouldn’t it be better to practice the Dharma?” Thoroughly bewildered, the exasperated man queried his spiritual master, “But what does that mean? I thought I have been practicing the Dharma.” The teacher responded concisely, “The practice of Dharma is to change your attitude towards life and give up attachment to worldly concerns.”

The real Dharma practice is not something we can see with our eyes. Real practice is changing our mind, not just changing our behavior so that we appear holy, blessed, and others say, “Wow, what a fantastic person!” We have already spent our lives putting on various acts in an effort to convince ourselves and others that we are indeed what in fact we aren’t at all. We hardly need to create another facade, this time of a super-holy person. What we do need to do is change our mind, our way of viewing, interpreting and reacting to the world around and within us.

The first step in doing this is being honest with ourselves. Taking an accurate look at our life, we are unafraid and unashamed to acknowledge, “Everything is not completely right in my life. No matter how good the situation around me is, no matter how much money or how many friends or how great a reputation I have, still I’m not satisfied. Also, I have very little control over my moods and emotions, and can’t prevent getting sick, aging and eventually dying.”

Then we check up why and how we are in this predicament. What are the causes of it? By looking at our own life, we come to understand that our experiences are closely linked with our mind. When we interpret a situation in one way and get angry about it, we are unhappy and make the people around us miserable; when we view the same situation from another perspective, it no longer appears intolerable and we act wisely and with a peaceful mind. When we are proud, it’s no wonder that others act haughtily to us. On the other hand, a person with an altruistic attitude automatically attracts friends. Our experiences are based on our own attitudes and actions.

Can our current situation be changed? Of course! Since it is dependent on causes—our attitudes and actions—if we take responsibility to train ourselves to think and act in a more accurate and altruistic way, then the current perplexed dissatisfaction can be ceased and a joyful and beneficial situation ensue. It is up to us. We can change.

The initial step in this change is giving up attachment to worldly concerns. In other words, we stop fooling ourselves and trying to fool others. We understand that the problem isn’t that we cannot get what we want or once we do get it, it fades away or breaks. Rather, the problem is that we cling to it with over-estimating expectations in the first place. Various activities like prostrating, making offerings, chanting, meditating and so on are techniques to help us overcome our preconceptions of attachment, anger, jealousy, pride and closed-mindedness. These practices are not ends in themselves, and they are of little benefit if done with the same attachment for reputation, friends and possessions that we had before.

Once, Bengungyel, a meditator doing retreat in a cave, was expecting his benefactor to visit. As he set up offerings on his altar that morning, he did so with more care and in a much elaborate and impressive way than usual, hoping that his benefactor would think what a great practitioner he was and would give him more offerings. Later, when he realized his own corrupt motivation, he jumped up in disgust, grabbed handfuls of ashes from the ashbin and flung them over the altar while he shouted, “I throw this in the face of attachment to worldly concerns.”

In another part of Tibet, Padampa Sangyey, a master with clairvoyant powers, viewed all that had happened in the cave. With delight, he declared to those around him, “Bengungyel has just made the purest offering in all Tibet!”

The essence of the Dharma practice isn’t our external performance, but our internal motivation. Real Dharma is not huge temples, pompous ceremonies, elaborate dress and intricate rituals. These things are tools that can help our mind if they are used properly, with correct motivation. We can’t judge another person’s motivation, nor should we waste our time trying to evaluate others’ actions. We can only look at our own mind, thereby determining whether our actions, words and thoughts are beneficial or not. For that reason we must be ever attentive not to let our minds come under the influence of selfishness, attachment, anger, etc. As it says in the Eight Verses of Thought Transformation, “Vigilant, the moment a disturbing attitude appears, endangering myself and others, I will confront and avert it without delay.” In this way, our Dharma practice becomes pure and is effective not only in leading us to temporal and ultimate happiness, but also in enabling us to make our lives beneficial for others.

Thus, if we get confused about which tradition to follow or what practice to do, let’s remember the meaning of practicing Dharma. To cling with concrete conceptions to a certain religion or tradition is to build up our close-minded grasping. To become enamoured with rituals without endeavouring to learn and contemplate their meaning is simply to playact a religious role. To engage in external practices like prostrating, making offerings, chanting and so forth, with a motivation that is attached to receiving a good reputation, meeting a boyfriend or girlfriend, being praised or receiving offerings, is like putting chocolate frosting into garbage: it looks good on the outside, but it’s unhealthy.

Instead, if everyday we center ourselves by remembering the value of being a human being, if we recall our beautiful human potential and have a deep and sincere longing to make it blossom, then we’ll endeavor to be true to ourselves and to others by transforming our motivations, and consequently, transforming our action. In addition to remembering the value and purpose of life, if we contemplate the transience of our existence and of the objects and people that we are attached to, then we’ll want to practice in a pure way. Sincere and pure practice that leads to so many beneficial results is done by applying the antidotes that Buddha prescribed when afflictive attitudes arise in our minds: when anger comes, we practice patience and tolerance; for attachment, we recall transience; when jealousy arises, we counter it with sincere rejoicing in others’ qualities and happiness; for pride, we remember that just as no water can stay on a pointed mountain peak, no qualities can develop in a mind inflated by pride; for closed-mindedness, we let ourselves listen and reflect on a new view.

Looking holy and important on the outside brings no real happiness either now or in the future. However, if we have a kind heart and a pure motivation free of selfish, ulterior motives, we are indeed a real practitioner. Then our lives become meaningful, joyful and beneficial for others.

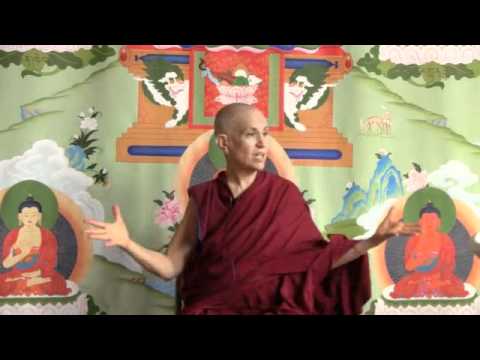

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.