The courage to be happy

A Crown Ornament for the Wise, a hymn to Tara composed by the First Dalai Lama, requests protection from the eight dangers. These talks were given after the White Tara Winter Retreat at Sravasti Abbey in 2011.

- Miserliness is based on fear: if I give then something bad will happen

- The things we can be miserly about

- Relaxing the mind and giving brings us peace

The Eight Dangers 14: The chain of miserliness, part 3 (download)

Okay, so we’re still on miserliness.

Binding embodied beings in the unbearable prison

Of cyclic existence with no freedom,

It locks them in craving’s tight embrace:

The chain of miserliness—please protect us from this danger!

Miserliness is the mind that doesn’t want to share, that doesn’t want to give, the mind that says, “I want, I have, I need, you can’t have.” And it’s often very fear-based, because if we give there’s a feeling of poverty afterwards. That’s why in the mandala offering it says, “I give without any sense of loss.” So to create the mind that can give without feeling impoverished afterwards. But miserliness can’t do that, it holds on and it feels, “If I give, I won’t have.” And then, “If I don’t have, something bad’s going to happen to me.” And so we hold on to stuff, clutching, clutching, you know?

So we can be miserly about material things. That’s what we usually think of is that. But we can also be miserly about our time. You know? And it’s like, “This is MY time. I’m not going to do that for you. Don’t ask me to do anything for you. I’ve done enough. This is MY time. *I* need a break.” You know that mind? Or it could be MY space. You know? “I need MY space.”

That’s a very interesting concept to actually investigate. What do we really mean when we say, “I need my space.” Is it outside space? Is it inside space? What is this space we need? But you know, it’s like, “I’m not going to give up my space. I need MY space.”

And we do that, of course, with physical things: “This is MY book, you can’t have it.” Yes?

And so, with time, our space, our material things … So it’s very interesting to look at that mind of miserliness, because it is very fear-based. You know? “If I don’t hold on to this, something bad is going to happen to me.” Yes? And that’s not a very pleasant feeling. And so we hold, but the holding doesn’t really remove the fear. Because the fear is always kind of lurking there in the back. “Somebody could take this away from me. Then what?” Okay?

So we use miserliness as a protection, but how well does it really work? Versus what kind of mental state do we have when we just drop the miserliness—and really drop it, not pretend to drop it, but still cling, but really drop it—and be able to give just because we like to give. Because when we’re not possessive in that way then there can be a real sense of peace and joy in our mind. You know? Somebody needs something, I give. And it feels good. And then the whole thing is over. Whereas with miserliness, they ask it, and, “No, I don’t want to give. You can’t have my time. You can’t have my energy. You can’t have my stuff. I’m keeping it because I need it and I’m important, and everybody always exploits me and it’s time for me to stand up for myself and say what I want.” And we clutch and cling. And so we say no. But then do we feel peaceful afterwards? No. We feel miserable.

And I remember this so clearly when I lived in Dharamsala, and I was very poor when I lived in Dharamsala. I mean really, really poor. But the beggars were poorer than I was. And when I walked to town to buy vegetables I would go past these certain beggars that lived in the community and it was so difficult for me to offer 25 paise—which at that time was about four cents—to them, so that they could get a cup of tea. To give four cents was like so excruciating. You know? And so I would try and think of all these rationales why I shouldn’t do it and couldn’t do it and blah blah blah, so I could walk past them. But I would keep my four cents, and I didn’t feel very happy. Even though the miserliness was supposed to make me happy.

So you see so clearly here how that afflictions causes pain. Whereas, if we relax and just decide to give— It doesn’t mean we need to give everything and bend over backwards and, you know, be a martyr. But just relax the mind and share. Then there’s peace in the mind, there’s joy in the heart, and nothing hurts afterward.

So I think Tara’s protecting us from the danger of miserliness by helping us learn to have the courage to be happy.

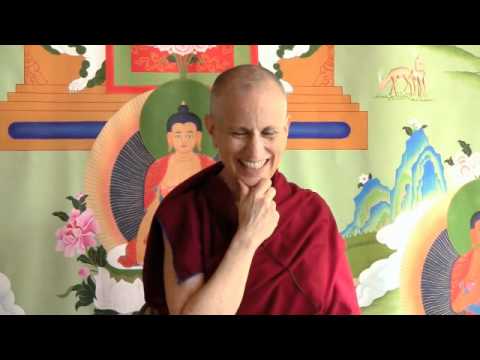

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.