The noble eightfold path

Part of a series of talks based on Taming the Mind given at Sravasti Abbey’s monthly Sharing the Dharma Day from March 2009 to December 2011.

- The fourth noble truth, the path to cessation, in terms of the noble eightfold path

- How the noble eightfold path is organized under the three higher trainings

- Practices related to each of the eight limbs

Taming the Mind 03: The noble eightfold path (download)

Let’s rejoice in our great fortune in having this precious human life with all of its freedoms and fortunes, in having bodies and minds that function well, in having all of our physical necessities met, in meeting the Buddha’s teachings that are present in our world given to us by qualified Mahayana teachers, and in having a supportive circle of friends. Let’s rejoice in that and open our hearts to the Buddha’s teachings, making a commitment, an aspiration, to integrate them into our lives to the best of our ability for the long term goal of freeing ourselves, for good, from the unsatisfactory conditions of cyclic existence. And let’s commit to freeing ourselves from the cycle of aging, sickness, death, and rebirth over and over, with the final goal of our enlightenment for the sole purpose of benefiting all living beings and bringing them to that same permanent peace.

We are going to continue working with Taming the Mind, a book Venerable Thubten Chodron wrote a few years ago. It’s a lovely, very accessible book about how we live and bring meaning to our lives, how we transform our minds into peace and wisdom. And it starts from the very practical basis of having to deal with our aging parents, wild children, difficult colleagues, and an environment that’s changing moment-by-moment.

Today, we’re going to spend some time talking about the noble eightfold path. Venerable Tarpa gave a lovely sharing last month on the fourth noble truth, and today we’re going to focus on when the Buddha reached enlightenment and saw, through the truth of duhkha, which is our situation here in this world: the causes of it, the fundamental ignorance causing us to perceive our reality as concrete, independent, permanent, and unchanging, and our continual maneuvering, planning, and strategizing to find happiness in something that doesn’t exist. Also, we’ll discuss this experience of finding the way of liberating ourselves from this cycle of unsatisfactory conditions and setting up a very beautiful structure that gives us the possibility of attaining exactly what we seek—which is a peace that does not end—for the benefit of not only our own wellbeing but also to bring all living beings along with us to that final goal of enlightenment.

The three higher trainings

It’s the fourth noble truth that we’re going to be spending time with today, and in our tradition it’s called, as Venerable Jigme put it beautifully in that analytical meditation, the three higher trainings of ethical discipline, concentration or meditative stabilization, and wisdom. A number of traditions—and Venerable Chodron goes through it in nice detail in this book—call this the Noble Eightfold Path; the Mahayana call it the Eightfold Noble Path. And those eight factors are organized into the three higher trainings. So, we’re going to split them up today one-by-one and see how they work together and relate to one another and build on each other; we’ll be able to have, perhaps, more clarity on those three very focused questions that Venerable Jigme put into the meditation because this is a lot about the eightfold noble path, which is a response to those questions specifically.

Ethical discipline

I’m going to use an analogy, because we have Gotami house in our mindstreams these days, and I’m going to take the three higher trainings and put them into the analogy of building a nice building that’s going to last. The first three of the Eightfold Noble Paths come under the higher training of ethical discipline. And my analogy is that ethical discipline is like the foundation, the framing, the roof and the siding of a well built house. This is what everything else is really going to rest on. And so it is with the foundation of any spiritual practice because it improves the quality of our lives from the get-go. There is a Theravada monastic—a Westerner—named Bhikkhu Bodhi who wrote the book The Noble Eightfold Path, and I used his book in correlation with Venerable’s book here. In his book he states:

The observance of ethics leads to harmony in our lives in four particular ways.

This leads to social harmony because any family, community, or society that lives by the principle of ethics would—if not eliminate—subdue all conflict, all wars, all misunderstandings, and all miscommunications. So, socially, ethical discipline is a fundamental way to find harmony. Psychologically, it brings us a peace of mind, a kind of peace where we can actually sleep at night knowing that we are practicing right action, right speech, and right livelihood. Karmically, doing so creates the causes and conditions for us to have future rebirths where we can continue to cultivate all the virtuous qualities in our mind and subdue all the negative qualities. And then as far as contemplation, by practicing ethical discipline we then get to have a mind that is much more focused, much more clear, and goes into these very subtle stages of awareness that we require to actually transform our minds and to develop wisdom.

So, right off the bat, ethical discipline is a win-win situation, not only for ourselves but for everybody around us. Within the first of the three factors of the Eightfold Noble Path, following ethical discipline is right action. And Venerable Chodron has given these teachings about how to abandon the ten non virtuous actions and how to cultivate the ten constructive ones, but putting them under ethical discipline, for me, gave them much more power, much more importance and much more significance because this is where I get to integrate them into my life on a daily basis. So, right action covers abandoning the three destructive actions of killing, stealing, and sexual misconduct.

Abandon intentional killing

To abandon intentional killing in any form, not just with other human beings, is where we as a family of human beings have got to step up to the plate and bring this virtue of nonkilling to a whole other level, because this includes animals and insects. We have a multimillion dollar industry in this country that gives us the tools and the mechanisms and services to basically annihilate and eliminate most of the animal and insect realms. And if we’re going to practice this particular life action, we’ve got to take into account that every living being, regardless of size or what it does to us, deserves more than anything to be happy and not suffer. The animal and the insect realm don’t have possessions, status, fame, chocolate cake, or beautiful houses. They have little lives that sometimes last only a few days or sometimes last decades. That’s the only thing that they have, and for us to cultivate right action, we’ve got to bring them into our lives as something to respect, to take care of, and to honor.

So, the virtuous counterpart of killing is to have a loving, kind, and considerate respect for all living beings; it’s to actually protect them—not just to stay out of their way, but as much as we can, to protect them.

Abandon stealing

The second of the right actions is to abandon stealing, which is taking things that are not freely given. And this one is not as apparent, so our culture kind of gives us a little bit of an unspoken permission to do this—sometimes in our places of employment and especially now with the economic downturn. Our health insurance is getting taken out of our paycheck, and our our 401s, and sometimes we find a way to justify taking things from the places where we work because we’re not getting paid enough, or we’re not getting a vacation, or the retirement that we want. There’s this unspoken condoning of taking things that are not given, particularly from our workplaces. We think, “The government is taking way too many taxes, so if someone wants to pay me $300 to clean the house or to work on the yard, or a $1000 dollars to remodel my house, and they want to pay me cash, I don’t have to tell the government about that.”

This is a place where we have an opportunity to practice caring for other people’s possessions and cultivating the mind of contentment with what we have. That’s the counterpart of stealing—to be content with what we have, and to honor not only our own but all others’ possessions.

Abandon misconduct

The next of the three right actions is abandoning sexual misconduct, and this generally refers to adultery: having sexual relationships with others who are in intimate relationships or marriage with another, or stepping outside of our intimate relationships and having sexual relationships with others. But on a bigger, deeper level, it’s refraining from any type of sexual misconduct that can cause physical and mental harm to ourselves or to others.

And the virtuous counterpart of this is fidelity, faithfulness, and staying in the commitment that we’ve made if we are in a continuous relationship with others. Right action brings us into an awareness of how we affect other people. “I want what I want when I want it,” gets totally reconsidered when we first think about how our actions affect other beings. And bringing that into our body and our speech—before we step into action—is to think, “How this is going to affect other people?”

Right speech

The second item under the factors of ethical discipline is right speech, and this is in regards to abandoning lying, slander, harsh speech, or idle talk. Sometimes the effect of our speech on others is not as apparent as the actions of our body, but this one is extremely slippery, and a part of it includes (and this is what Bhikkhu Bodhi shared, and I agree with it) the written word. The power of the written word, as far as lying, slander, harsh speech and idle talk are concerned, is just as crucial, and with our communication and technology that we have, the non virtuous words that get written can be heard and seen throughout the world. They are the cause of conflict and misunderstandings; they create enemies, and they break lives. The virtuous counterparts of these create harmony; they create peace, and they heal divisions. So, speech is a very powerful tool as far as cultivating ethical discipline.

Abandon lying

We begin right speech with lying, which is not just a word, but it could also be a shrug, a nod—anything that indicates an intention to deceive. And we know that while living in a family or a community or a society, we can only live together well if there is an atmosphere of trust in which we can say, to the best of our ability, what we understand to be true. And we know that with distrust and suspicion—when it becomes widespread—lying, by its very nature, proliferates. If you tell an untruth, you have to cover that with another untruth, which then escalates to another untruth, and there goes trust, and there goes confidence and people’s wanting to confide in you. It really does build a lot of distrust and suspicion in the world.

The counterpart to that is to be as truthful as possible, to keep confidences well if they do not harm—to be as truthful as we can.

Abandon divisive speech

The second item in right speech is abandoning divisive speech, which causes people who are struggling to quarrel or causes people not to be able to reconcile. Bhikkhu Bodhi addresses the motivation of slander. It took me a little bit to think that what motivates us to slander is usually jealousy at another’s successes or virtues. If we are infatuated with someone who’s in a relationship that is faltering, that sometimes motivates us to cause even more division in that relationship because we really want one of those two people.

There’s a strange glee in the human family of actually seeing friends having difficulty, which is a hard thing to actually admit to. But I can admit that at certain times in my life, the jealousy would come out as wanting things not to succeed in my friends’ lives. So, this is talking about perpetuating a sense of failure in that relationship.

Its virtuous counterpart is to bring people together with harmonious speech, which originates in the mind as kindness and empathy. It wins the trust and affection of others who then feel that they can trust you with their deepest, heartfelt wishes and aspirations. And the karmic results of harmonious speech are that you’re going to have trustworthy friends in the future. They are going to care and respect you very much.

Abandon harsh speech

The next one under right speech is harsh speech, which harms, ridicules, humiliates, and insults people. So, we want to abandon this. This can be done with a growl or this can be done with, as Venerable Chodron says, a very sweet, innocent smile on our faces. It’s praising people, or so it seems on the surface, when in fact we’re demeaning them by putting a little bit of sarcasm or shame into the process.

The counterpart of this is to be tolerant of blame and criticism that comes your way, to be tolerant of other people’s shortcomings, and to be open to other people’s points of view.

Abandon idle talk

And then lastly, as far as right speech goes, there is abandoning speech about things that are inconsequential, that have no value, that are meaningless. I think, particularly in the Western world, this is one that we have a hard time with. We have an industry, we have newspapers, we have television shows that make billions and billions of dollars a year and which fill our minds with all the things, particularly the bad things, that are happening to movie stars, sports heroes, and political figures. These meaningless things fill our newsstands and they fill our television channels with what’s going on in the lives of all of these people.

Now, Venerable Chodron is very clear that there are relationships in our lives that we make a connection—with our families, with our friends, with our colleagues—when we talk about the weather, “How’s Uncle Joe doing after his surgery?” “How are the kids doing in school?” These conversations are part of the way in which we connect with one another. Those relationships that are intimate or not so intimate, we make connections by talking about things that on the surface don’t have any value, but it keeps us connected to our larger society.

However, we need to be careful because this can so easily slip into nice, juicy tidbits about people’s lives that you heard from a friend of a friend of a friend, and then we get into divisive speech and harsh words. So, on one hand, it connects us to the world in a certain way, but we have to be very careful. The virtuous counterpart of that is to talk about Dharma, to talk about things that directly benefit others. And to speak about other people’s good qualities behind their back is a wonderful way to counteract idle speech.

Right livelihood

And then the third point underneath ethical discipline is right livelihood. I find this a helpful one. Since we all need to sustain our lives, to put a roof over our heads, to put food on our tables, take care of our families, and support our friends, we need to choose a livelihood that does not harm others. The obvious ones are butcher, hunter, manufacturer of weapons or chemicals for warfare, or any kind of substances that can harm living beings such as making illegal drugs. Those are the apparent ones. We’re only able to choose the livelihoods that we feel that we can do ethically.

We have no control over what members of our family do, what societies, or what our countries do. We can only—to the best of our ability—choose a livelihood that will benefit others and not cause harm. There are some circumstances and situations where you live in a small town, and the biggest employer is a casino or a prison. If that’s how you put food on the table, do the best you can. You come into the livelihood with a sincere motivation not to harm, and you do the best you can.

Underneath this Bhikkhu Bodhi also shares that there is a part of the Thai tradition treatise on right livelihood titled “Rightness regarding action, rightness regarding persons, and rightness regarding objects.” Underneath this heading is that workers need to fulfill their job diligently and honestly, conscientiously, not hanging around idly talking, claiming hours you haven’t worked, or pocketing the company’s goods. So, if you’re going to work for a company as an employee, this means to really do it the best you can, as honestly as you can. The rightness of persons is respect and consideration for employees, employers, merchants, and customers. The employer is to actually give their employees jobs that they have the ability and capacity to do well, to pay them adequately for their efforts, to promote them when they can, and to reward them when possible so the employees, in return, can be diligent and conscientiously do the best they can. Colleagues should cooperate rather than compete, and merchants must be fair in dealing with customers. That’s regarding persons.

And the right liveliness regarding objects is to always represent what you’re offering—whether it be a service or goods—as honestly as you can and to not have any deceptive advertising or misrepresenting of the quality or the quantity of what you offer. These are the subheadings under right livelihood. If we take some of these into account when we’re looking for work, it will certainly narrow the field, and it may open up some possibilities that you may not have considered.

Three destructive actions of mind

Then there are the three destructive actions of mind which we want to abandon: covetousness, maliciousness, and wrong views. These are not generally under right action and right speech, but Venerable Chodron says it’s very important to cultivate goodwill, once again being content with what we have, and not figuring out how to get something that somebody else has. To have questions about the Dharma is to cultivate a good sense of curiosity while wrong view is to have a vigorous skepticism and a lot of anger, and an attitude of, “Show me; I don’t believe you,” and “I don’t believe in rebirth. I don’t believe in the Buddhadharma or in liberation.” It’s not the kind of doubt that arises from wanting to know the answers to your questions and a heartfelt way to of being open minded to understanding, rather it’s the kind of wrong view that just wants to disagree and argue for the sake of arguing. It has no intention of changing one’s mind. So, as Venerable Chodron says, “We want to cultivate open heartedness and contentment, and to rejoice in others’ good fortune.”

Higher training of concentration

The analogy that I think about for the second set of factors that fall under the higher training of concentration is the plumbing, the heating, the electrical systems, the sheetrock, the flooring—the stuff that on the surface you may not be able to see, but if they weren’t there, the house wouldn’t be useable, wouldn’t be livable. Concentration is kind of like that. We’re talking about cultivating qualities of the mind that on the surface, on the outside, people don’t know are there, but without them we cannot have a livable environment.

The first of these, concentration, is a vital part of the path because without it we won’t be able to focus on a virtuous object for any period of time. If we’re going to cultivate wisdom realizing emptiness, we need to have a mind that is subdued, clear, stable, and focused enough to be able to do that as long as we want.

Right effort

So, the first factor underneath right concentration is right effort, and this is an important factor along the path. Ethics, wisdom, and concentration all contain this, but it’s particularly put under the higher training in concentration, and it is a wholesome kind of energy which arises from wholesome states of mind. Once again, Bhikkhu Bodhi explains that the Buddha stressed this quality over and over again in his teaching for forty five years. He used the terms “diligent exertion,” and “unflagging perseverance,” because he realized very clearly that the path to liberation and enlightenment is a long one, and that he could only point the way; he couldn’t do it for us. It is our responsibility to work our way out of the cycle of existence. And having an unfaltering, unremitting energy for the path is the way to succeed.

At the starting point is our deluded, confused minds; the goal is liberation and enlightenment; and the space between those two is long and arduous. Without right, joyous effort, it’s not going to happen. The task is not easy, but the Buddha and 2600 years of realized practitioners and teachers have verified as living testimonials that it is possible. This particular quality—the one that His Holiness phrases as “Never give up”—is right effort. They are our living proof that if you’re practicing the path with great perseverance and stamina, you will accomplish the goal.

Right mindfulness

The second of the factors under concentration is right mindfulness, which is a mental factor that enables you to remember the virtuous object that you are focused on. Mindfulness of the ten constructive actions brings the virtue of ethical discipline into a deeper level of understanding. It also helps in meditation because it counteracts the minds of forgetfulness, laxity, and excitement. This is the remembering aspect of meditation; it continually brings the mind back to the virtuous object, whether it’s the Buddha, loving-kindness, ethical discipline, compassion, love, etc. Over and over again, it remembers the object and keeps coming back and back and back.

And there is another whole explanation of mindfulness—in the Theravada tradition—which I didn’t get into, and which is a lovely piece. But this is what we’re going to focus on today: this repeatedly returning our attention to a virtuous object, over time, brings stability and strength to our meditation. It sounds very simple, but it’s very difficult. Over time it brings us strength, and it is the stability—the ability to not wander off every after every distracted thought that walks by or floats up. Mindfulness keeps us totally focused on the object by remembering it over and over again.

Right concentration

And then right concentration is a single-pointedness on the object of meditation. This factor arises slowly through right effort and right mindfulness. Concentration, in and of itself, is something that Buddhists and non-Buddhists do. This is something that any focused mind requires, whether it be a potter throwing a vessel, a sniper, or a scientist in a lab trying to put together a complicated theory. All of that requires very focused, undivided attention. All the sense consciousnesses are not distracting you; you’re not hearing anything because you’re so focused on the object. In the Buddhist tradition this is the state that we want, but we also want to have a deliberate attempt to raise the mind to a very subtle, pure level of bare attention.

And this is sustained by virtuous thoughts of refuge, the determination to be free, bodhicitta—these are like the food of this particular one pointedness, the motivation behind this sustains this level of concentration. Many non-Buddhists find this place. Apparently it is that deep, single pointed level of concentration that with a very subtle mind that generates an extreme level of bliss in the mind; this is something that they say is not even comparable in the world of the senses. We want to get to that, but that’s not the goal. The goal is to use that subtle level of single-pointed concentration to realize the wisdom, the ultimate deeper mode of existence. So, we get to that place, but then we go farther, because we want to realize the emptiness, to attain liberation and enlightenment.

These are the factors involved, the level of concentration we need to transform our minds into realizing emptiness directly. The mind has to be refined, stable, focused, subtle, and free of any distractive thoughts for a long, long period of time.

Higher training of wisdom

And then finally, the last two factors of concentration, which are right intention or thought and then right view, are subsumed under the higher training of wisdom. And the analogy that I continue with is that wisdom is the windows and the doors, the ones that open up to the moonlight, the sunlight, the fresh air, the ones with the panoramic view of all things. We are living ethically to eliminate the non virtuous actions, the distractive, discursive thoughts. Concentration subdues those afflicted states of mind, but without wisdom there is no way to liberate ourselves. We’ll just continue with rebirths in cyclic existence.

To eliminate the cause of all of the duhkha, the ignorance, the fundamental misunderstanding of how things really exist, we need to realize the emptiness of the inherent existence of ourselves and all phenomena to recognize how things really exist. To do this, we have to practice special insight—called Vipassana—which is the discriminating wisdom that arises from the deep analysis of the modes of existence.

We’ve got these beautiful, profound, analytical meditations in the lamrim around emptiness and dependent arising. The piercing study, understanding, and contemplation of how things exist by understanding the emptiness of inherent existence of the self, the dependent arising of all phenomena—the wisdom that arises from understanding that intellectually, inferentially—that is the Vipassana, the special insight. It’s one of the pieces in the wisdom practice.

The other one then is Samatha, which through this deep concentration we get into subtle states of mind, but until we realize emptiness, those two things don’t live together. The analysis, the deep analysis, brings us to a level of understanding, but it disturbs the level of concentration because one is on a more conceptual level, and then the other one is more the direct experience inside the mind. These two things we learn simultaneously, but initially they don’t go together. It’s one or the other.

And then when we get to the point where those two conjoin: the deep piercing understanding of how things are inferentially focused with a mind that is stable, focused, subdued. When they conjoin together, that’s where this direct perception of emptiness arises. This is my understanding of what I read, because I have no—even no intellectual—understanding of either of those two things. I basically took it right out of the book. It says:

To do this, we practice special insight, which is a discriminating wisdom, that joins the pliancy and stability achieved through concentration induced by the power of that analysis.

Until we attain Vipassana—this powerful, discriminating wisdom—whenever we do analytical meditation, our concentration is disturbed. We’ve got to do this thinking, this understanding, and this deep level of awareness; they don’t reside together in the beginning. This Vipassana makes the mind very powerful as far as the level of understanding.

When this powerful state of mind is concentrated on looking at the emptiness of inherent existence of the self, it then cleanses our mindstreams of the ignorance, this misperception, as well as all the afflictions, the karma, and the imprints that follow.

We’ve talked about this inference of understanding emptiness—that it’s still on the intellectual, deeply intellectual, level of the mind. And then there’s the state of the mind itself that can stay on a virtuous object, focused on a very subtle level, and then somewhere along the line, those two interconnect. And that’s when the direct perception of emptiness arises—someday.

Right view

The right view or understanding is the understanding of the Four Noble Truths. It’s the wisdom that opposes the deluded views, such as the concept of inherent existence and the grasping at a solid I—the body and mind being solid and existing independently from their own sides. The right view is understanding that this is not true, it opposes the deluded view.

Right thought

And then the right thought, or intention, has three explanations: there are the factors of nonattachment or renunciation, benevolence or goodwill, and harmlessness. When the thoughts are wholesome, or the intention is right, the actions will be right. This is very important when we want to generate the right view. We’ve got to have these three factors involved in our intention. And I would put in, probaby, the deep intention of bodhicitta. On a deeper level, right thought refers to the mind that subtly analyzes emptiness, which in turn leads us to perceive it directly. And in the book, Venerable Chodron says, “I’m going to talk about this later,” so she was very general in the wisdom training in this chapter.

By taking care of our bodies, watching our speech, and training our minds, we can practice the Eightfold Noble Path. It’s called noble because those who have practiced these eight factors and achieved liberation and enlightenment are called arya beings: those who have perceived emptiness directly. The noble in “Four Noble Truths” and the noble in “Eightfold Noble Path” refer to the mind of these arya beings who have taken each and every one of these eight factors and have lived them, integrated them into their lives, and realized them completely in their mindstreams.

This is the first time I’ve seen it just so beautifully laid out as a systematic, organic structure. I’ve always wondered how the Eightfold Noble Path had anything to do with the three higher trainings; now I know. And the Buddha said that practicing the Eightfold Noble Path will give rise to vision, will give rise to knowledge, and will lead to peace, direct knowledge, to enlightenment, and to nirvana. So, he has signed on the dotted line and said that if you follow the Eightfold Noble Path and integrate it into your life, I can guarantee—I can assure you unequivocally—that you will attain liberation and enlightenment.

I did want to share something that Venerable Chodron has said a number of times. When I first heard the Four Noble Truths, I thought, “You know, I’m not sure about this Dharma because it talks all about this suffering stuff. It’s so pessimistic.” It said, “Yeah, life is suffering; death is suffering.” But, Venerable Chodron remembers that—even when she was a little girl—she had questions. My niece asked these questions of me one time, too: “What is the meaning of life? Why are we here? What is this all about?” Being raised in a world that said, “Well, you get married, you have a family, you buy a house, you buy a car, you get status, fame, and reputation is normal.” Her story is that though she kind of went through that, she didn’t get the answers to her questions.

When she first heard the teachings on the Four Noble Truths—and I don’t know when she saw that flyer and went to that meditation course, whether it was Lama Yeshe or Lama Zopa—when they talked about the four noble truths Venerable Chodron experienced a deep sense of relief because she finally said somebody was telling her the truth. Because her experience of her life was that happiness is not about having a car, getting married, having a job, a profession, or an education. There was something deeper that she was missing, and life was just unsatisfactory.

To have this Tibetan lama come in and say, “That’s right, child, dear. Life is dissatisfaction, but there’s a way.” There is a teaching in this world that validates, says that’s true, and there’s a way out of it. I think the whole karma of her life with the Dharma came from that teaching. I have been able to turn my mind—particularly over the past five years—to seeing the Four Noble Truths as one of the most liberating, life-affirming, and empowering teachings of the Buddha; and this is why he stepped into the world with that teaching; the first thing that ever came out of his mouth was the Four Noble Truths—and how empowering and how liberating that is.

The Eightfold Noble Path is the way in which we achieve liberation and enlightenment. I found this particular sharing of this today very inspiring for my own practice, and it has brought the four noble truths into my top teaching to integrate into my life.

Questions & Answers

Audience: I had a question about right thought. Like on a deeper level, how is that any different from right view? How does it fall under there?

Venerable Semkye: I have the same question. Venerable Chodron says that will be discussed more in depth in the section on wisdom. I don’t know the answer to that question of why right view isn’t the higher training of wisdom in and of itself. And also I had some of the same questions when we got into right concentration, as a higher training that has these three subheadings—you can see how they build on one another, but yet there’s similarity in there. I just don’t have the ability to see the differentiation between right concentration as the Eightfold Noble Path factor and the higher training, how they’re different as far as the subtleties. So, I would very much like to ask that same question.

Audience: Kind of towards the end, defining the word “noble” that we use with liberation and enlightenment: my understanding is that’s not correct, that noble is an arya being but not an enlightened being under this?

Venerable Semkye: Yes, thank you. It’s the mind that realizes emptiness directly. Enlightenment is another whole thing.

Venerable Tarpa: They use that word differently in different traditions. I think in the Pali tradition they use the word enlightenment or nirvana, but we would not. We make quite a distinction. Nirvana, the Buddha, enlightenment—the whole deal: you see that very differently. So, it’s kind of confusing.

Audience: On the ethics stuff, I had a pretty big internal struggle when Venerable Chodron first talked about about not stealing by not paying taxes because when I came to the Dharma, I came out of left-field politics, and I was pretty active in war tax assistance. The government, of course, uses X percent to wage war. Around that time, I was kind of taking X percentage out and giving it to nonprofits or using it for my own family and saying this is a better use of it. So, I talked with her about it, and it’s still a little gray to me, but she gave me some adivce, and so this is what I did after I met her and for the next seven years when I had income like that—self employment, where you could do those kind of things. She said, “Pay all the taxes because that’s what other people are doing, and so the big pool of citizens, that is who you’re kind of taking from, because they’re all paying their share. And then what you do is you put in a letter every time you send your taxes that says, ‘It’s my intention that none of this is used to harm anyone, to wage war, or whatever.’” So I did that, and it felt a lot better, but every time the issue comes up, I still go through that struggle about giving the money over to a government that does some good things—roads and hospitals and education and—but also does some really horrific things. So, I do what she said because she’s my teacher, and I know she’s got clean, pure thoughts about it, but I still have this “grr” feeling about it.

Venerable Semkye: And that is where that little dent appears, where we’re only able to choose our own lives; we’re not able to control what other people in the country do. So, once again, we have other people’s harmful actions affect us to where we create non virtue. On the level that I am at, like closer to home, I would love to be able to control what my country does, but I think that’s where she puts just clarification.

Audience: So, it’s staying in your own square, keeping your own stuff clean. So, it would feel better, because what I was doing before, which also brought some stress and anxiety, thinking what if they audit me, and da da da da da. So, that was not so good. I could see her advice, you know, it became more clear.

Venerable Semkye: Yeah. And I’ve also seen it; I knew some people in my life that also did the same thing, but the mind that arose in discussion with them was a mind that had a lot of hostility and a lot of anger and judgment, too. To be squeaky clean, if you’re going to do that, is to have a mind that is very respectful and very understanding that you’re making a choice.

Audience: I was wanting to make an observation that conscription now is beyond, because military service is voluntary. At the time of conscription, they believed that taxation was a form of conscription, and many of them chose to earn more than the level which they would be taxed.

Venerable Semkye: Which I think—in our government—is about six hundred dollars a year. Oh, $14,000?

Audience: What does the word “ethics” mean? I have a lot of ways to follow ethics but not a clear definition of what it actually is.

Audience: Maybe anything that leads to suffering.

Venerable Semkye: I don’t know what the dictionary says, but for me, it’s practicing things that bring happiness to myself and others. I mean, that’s more like an activity, it’s not a way of thinking. I don’t know what the dictionary meaning is.

Audience: In the world there are people who are pursuing happiness but aren’t very ethical. I guess it depends on your definition of happiness.

Venerable Semkye: That happiness is quite limited. I think that’s why right speech and right livelihood are the guidelines for what ethics actually is. I mean, if I have to guard my speech in the exact way that the Buddha said, and I have to guard my actions in the same way he does in right livelihood, I believe that that is ethics. So, it’s more of a guideline. I’m not even thinking about a state of mind, more of an activity.

Audience: Yes, you have the activities laid out for us, but it’s kind of like a little too clean, and it’s hard to apply that to different situations that might not necessarily fall directly into that. By ethical discipline, in that situation, you have to have a clear understanding of just what ethical discipline is without… Of course the guidelines help me to adapt that to different situations. I think that while I know that in such and such situations this is unethical, I can kind of transpose that into different situations. So, I can understand that this is unethical, so they’re good in that way. I’m just thinking…

Venerable Semkye: I think that’s why the trainings on concentration and wisdom are components of each of the others because in some situations, unless I have a certain level of clarity in my mind, it’s like I can’t be ethical with having some other quality of the other two trainings involved, like discriminating wisdom.

Audience: Yeah, but still at some point in your mind, you have to make a decision about how you’re going to turn your mind. And you should do that based on ethics. So, in an actual situation, even if it’s extremely subtle, in that situation, I guess, you can do it based on wisdom. If you have wisdom. That might be okay, but we don’t all have wisdom.

Venerable Semkye: Because even in a situation of right speech, Venerable Chodron said that there were situations in which telling the truth could harm somebody. Let’s say there was a woman who was looking for protection, or a partner who is looking for protection from a violent spouse, and they came to the door, you would have to somehow be able to not tell the truth for the benefit and the safety of that person. So, it’s almost like—like you’re saying—the situation brings up a choice that has to be made to the best of your ability, trying to cause the least amount of harm. I mean, it’s not a black and white situation.

Audience: A definition would be helpful to apply. Not harmfulness sounds more like it.

Venerable Chonyi: Well, that’s why the three practices of ethical discipline in the Mahayana are not to harm, to benefit others, and to accumulate virtue. So, that’s pretty clear. Yeah, it’s more general, but the direction is quite clear.

Audience: I think of ethics, and I think of how we relate socially as interacting with others so all the things of ethics involve what I would think of as “the greater good.” For individuals, so not just one person, but we have ethics where you act ethically in terms of society.

Ven. Semkye: Socially, psychologically, Dharmically…

Audience: I think it goes back to it is there to regulate our behavior, but in a way that we would want it to be for the greater good. Personally, it’s a mutual kind of thing for me, another person, for the family, for society. So, at some point it might be more ethical not to do your meditation. So, you can say your meditation is quite important, but if there’s someone in greater need who could benefit from you.

Audience: In the past, you’ve talked about the difference between those things that are generally ethical. He often talks about things that everyone would consider ethical regardless of spiritual background, things that everyone—

Venerable Semkye: Naturally negative actions.

Audience: We talked about bringing to that your particular Buddhist perspective and he’s talked a number of times. Talking about ethics, everybody has some rules of some kind, and your ethics are based on your mind that we all have. Even drug dealers have ethics of a kind. There is behavior and consequences of following or not following ethics. These are absolutely intertwined. It’s nice to speak of focus, it’s an aspect of it. It’s natural for us to say, “How is this different from that?”

Venerable Tarpa: We can’t divorce it from part of the wisdom that has to do with the wisdom related to karma, the parts of karma that relate to intention. That kind of ties the whole thing together.

Venerable Semkye: Under ethical discipline there is right action, right speech, and right livelihood. Under concentration there’s right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. And then under wisdom there’s right intention, or thought, and right view. It should be right view first and then right intention or thought. Quite a different ordering than traditionally. Now I’m curious; I want to know more about the subtler aspects.

Anyway, thank you for your questions and your comments, corrections. Let’s just spend a minute or two thinking about whatever struck home, or aroused some curiosity, or wanting to know more, or rejoicing. Once again remembering that, as in many of our thangkas, the Buddha’s up in the corner there. He’s pointing at the moon; he is the guide. And we ourselves are responsible for our own liberation and enlightenment. And to add that because of his great compassion, he laid it out in some clear, profound ways, and we have access to that today and can rejoice at that. And we can see how this eightfold noble path very much benefits others.

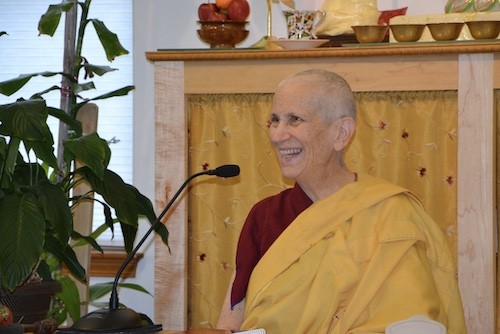

Venerable Thubten Semkye

Ven. Semkye was the Abbey's first lay resident, coming to help Venerable Chodron with the gardens and land management in the spring of 2004. She became the Abbey's third nun in 2007 and received bhikshuni ordination in Taiwan in 2010. She met Venerable Chodron at the Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle in 1996. She took refuge in 1999. When the land was acquired for the Abbey in 2003, Ven. Semye coordinated volunteers for the initial move-in and early remodeling. A founder of Friends of Sravasti Abbey, she accepted the position of chairperson to provide the Four Requisites for the monastic community. Realizing that was a difficult task to do from 350 miles away, she moved to the Abbey in spring of 2004. Although she didn't originally see ordination in her future, after the 2006 Chenrezig retreat when she spent half of her meditation time reflecting on death and impermanence, Ven. Semkye realized that ordaining would be the wisest, most compassionate use of her life. View pictures of her ordination. Ven. Semkye draws on her extensive experience in landscaping and horticulture to manage the Abbey's forests and gardens. She oversees "Offering Volunteer Service Weekends" during which volunteers help with construction, gardening, and forest stewardship.