The four seals

Part of a series of teachings on the tenet systems given at Sravasti Abbey in 2008. The root text of the teachings is Presentation of Tenets written by Gon-chok-jik-may-wang-bo.

Out of the numerous teachings the Buddha gave, these four teachings which we are going to talk about today are referred to as the “Four Seals” of the Buddha’s teachings. You may wonder, why be so selective of these four? These four are known as the Seals. There could be some teachings of the Buddha which may not hold true in some other time frame, or with some other individuals they may not hold true.

Say there is someone who is less interested in generosity, then the Buddha encourages the person, saying, “Oh, generosity is the best of the virtues, so why don’t you do that, otherwise you are going to miss the best opportunity for one’s own benefit.” Here, to encourage the person in a very skillful way, the Buddha said that generosity is the top, most important practice. Whereas, for someone else who is keen on the practice of generosity but yet not so keen on observing ethical discipline, then the teaching that the Buddha gave to the first person may not hold true in the case of the second person, because for them, there is no need to encourage generosity, but rather to encourage ethical discipline.

In that same case, you might say, “Oh, look, generosity is so good, but what’s the use if you don’t observe ethical discipline, because not observing ethical discipline will result in you taking rebirth in the lower realms?” So, the insufficient level of practice of generosity that you have developed—with some effort—may ripen in rebirth in the lower realms. In that case, you are unable to really further invest in the practice of generosity because, in the lower realms, you do not know how to multiply the virtues. You will simply be consuming the results of the virtue you have previously accumulated, and then, eventually, that virtue is going to be exhausted; therefore, in this current rebirth, ethical discipline is the top priority. Again, you see, there are different teachings that come out, so these teachings may not necessarily be in line with everyone’s interests, and may not hold true in all contexts.

However, the four teachings that you see under the heading, “The Four Seals of the Buddha’s Teachings” hold true in all respects—whether you are in the twentieth century, the twenty-fifth century, the thirtieth century, the ninth century, or the first century—and these four teachings hold true at all times. And not just for one individual but for everyone; therefore, these four teachings are known as “The Seals of the Buddha’s teachings” or “The Buddha’s Seals,” in that there is never any concession, there is never any kind of alteration required for these teachings. This is what is fixed: these four teachings will be as beneficial and true at all times for everyone at any place. These four teachings form the whole framework of Buddha Shakyamuni’s teachings for the benefit of oneself and all other sentient beings.

The four teachings

What are these four teachings? If there could be more teachings which hold true, which are also beneficial to oneself and others, then why only four? Again, if the number is many, we can easily get discouraged, or we become hopeless students. These four, in terms of number, are so small, and on top of that, these four can rightly encapsulate the complete form of one’s practice. That’s the beauty of this teaching.

What are these four seals? As we all know, there is going to be a little bit of difference in terms of translation, but, generally, we say:

- All composite things (some translators can offer you the translation “compounded;” these two just mean the same) are impermanent.

- All contaminated things are of the nature of suffering.

- Everything is of the nature of emptiness and selflessness.

- Transcending sorrow is peace and ultimate virtue.

Let’s see how these four teachings encapsulate the entire path and spectrum of the practice so that we can get to the state of nirvana or enlightenment. The teaching on these Four Seals can be expanded to all other teachings, and all other teachings can be abbreviated or shortened into these Four Seals of the Buddha’s teaching.

All composite things are impermanent

Before delving into this point, we need to know the reason that we practice the Dharma. Well, why are you sleeping? Why are you taking your breakfast? Or why do things that you like? Eventually, the answer is going to boil down to “I want happiness.” This is the ultimate answer. Obama and McCain are fighting for votes. If you ask them this question over and over, eventually they will come up with the answer, “I want happiness. I think this is how I’m going to gain happiness.”

If you ask a bodhisattva, “Why are you giving away your limbs, why are you giving everything away to everyone else?” They will say, “It makes me happy to see others happy.” Finally, the ultimate answer is again, “It makes me happy.” If you ask the Buddha the same thing, “Why do you destroy so much for three countless eons, ready to give up everything?” Again, it’s the same answer:“To benefit all other sentient beings.” We may respond, “Why is it that when you’re able to benefit all other sentient beings you are happy?” The bodhisattva replies, “Well, this is the greatest gift that I can expect. I am more happy to see others happy.”

But, the way you try to gain your goal—the happiness for one’s self—differs among the different individuals. Some, the least intelligent ones, the more ignorant ones, think that by pushing others away, they gain the benefit; they gain the happiness. Whereas, the more intelligent ones, like bodhisattvas and buddhas, know the reality; they know that it is not by pushing others away, but by embracing others, that we receive the greatest benefit. Eventually, we see that our ability to help others results from our own innate desire for happiness.

This is the beauty of Buddhism; you always keep asking questions. We come to know that happiness is the ultimate driver for everyone to move here or there; it is what drives the buddhas to work for the welfare of sentient beings, it is what drives the robbers to steal others’ things, and so on.

If you want to have a very sound meditation practice, the next question you should be able to ask yourself is, “I see that actually, deep down, what I am seeking is happiness for myself. What degree of happiness am I seeking: 10 percent? 20 percent? 50 percent? 100 percent?” If possible, we seek 100 percent happiness. But is it possible that 100 percent happiness is what you’re going to achieve?

You’re asking questions and the answers you get become so candid and clear, right? To resolve this question about whether or not you can get 100 percent happiness, the Buddha said that, first of all, we have to know what the obstacle is to achieving that 100 percent happiness. Do we have 100 percent happiness now? No, we don’t, which means that it’s so obvious that the obstacle is within us. This is a clear indication. Now our job is to explore, “What is that obstacle which gets in the way to achieving 100 percent happiness?”

We see that it is not just a physical body which gets in the way of achieving 100 percent happiness; it has to do with the mind. You’re in the same house, you’re with the same companions, and yet sometimes you feel so happy, and other times you feel so sad, so low spirited. Why is that? It’s not the physical body that is determining that mood, rather it is your own mental thinking. It must be something within the mind; the obstacle must be there within the mind. So, what is that? Again, we have to examine.

Say, just for a simple example, there is a rosary on the table, and you perceive it as a snake. Then naturally there is going to be fear in your mind. Even if there is a real snake there, this watch in my hand is not going to be afraid of the snake, whereas human beings are afraid. So, what is the difference? Humans have a special faculty known as “mind,” which can sense phenomena, which can cause fears, or which can feel happy when there is no threat—no snake—there. So, it is a mind, and on top of that, when you start perceiving the rosary as a snake, then there’s a fear arising in you.

This fear is what we dislike. It’s so painful. Just imagine someone about to be hanged. Look at his physical appearance: it’s so sad; it’s so desperate. We don’t like to even just have the appearance of it. You feel pity and such compassion for him. Similarly, his sadness is nothing but the fear of losing himself. With this example, this fear has arisen by this misconception of himself. The Buddha said that all fears, all dissatisfactions, all unhappinesses—the opposite of happinesses—are eventually rooted in what is known as ignorance or misconception of our own mental thinking.

For this question as to what is the obstacle that gets in the way of achieving 100 percent happiness, the Buddha points to ignorance as the final obstacle which gets in the way of achieving that. As soon as this misconception of mistaking this rosary for a snake is eliminated, removed, the fear automatically disappears. You see this rosary as a snake and then there’s a fear in you. It is useless for me to simply pray to make this snake go away so that I will not have fear. The wisest thing to do is to come to know that this is not a snake. If you come to know that, if you’re able to cultivate this realization—the knowledge which realizes that this is not a snake but rather this is a rosary—then the fear immediately dissolves. You don’t have to do anything else to remove this fear. Simply remove the cause of that fear and the fear will diminish on its own.

Ignorance is the root of unhappiness

What is the opposite of 100 percent happiness? It is 100 percent pain, or less than 100 percent happiness. What is that triggered by? What spurs that non-happiness? It is nothing the Buddha points to except the ignorance, which is the root cause of all these dissatisfactions. Our job is to simply get rid of this ignorance, and dissatisfactions will diminish on their own. Diminishing the dissatisfaction, at all degrees, is what is known as “accomplishing 100 percent happiness.” It becomes so clear now. Our job is to eliminate the ignorance within us. The next question is, “What is this ignorance?”

Once we know what this ignorance is, the next question is, “How do we eliminate it?” The Buddha points to this ignorance as the root cause of all pains, dissatisfaction, suffering, jealousy, attachment, aversion, anticipation, and so forth. The actual practice is not as simple as what I said. In terms of the actual practice, it’s not as beautiful as the blueprint that is put up there on the screen during the teaching, you know? In reality, there are all different things, different details, involved.

Similarly, although I name everything as just “ignorance,” in a true sense, there are various degrees of ignorances. One of the worst of the ignorances that traps us in all these dissatisfactions is viewing impermanent phenomena as permanent, viewing all composite things as permanent—primarily viewing one’s self as so permanent and everlasting.

Say I came here just for a few days or a week: what would you think if I tried to buy refrigerators and other things for this small cabin? What would you think? “Is he mad? Is he insane? He’s here just for a few days! Just to install these things will take a few weeks!” So, what point is there? You’re there just for a few days, so if you’re not insane you’re not going to do these things, because you know that you are simply a traveler. You are simply there as a guest for a few days.You’re not going to do things which will take you weeks and months when you’re only going to be there for just a few days. It’s just foolish, right?

But I might think I’m going to be here for more like ten years. Actually, I’m here just for a few days, but I don’t know that. And then I start complaining about the cabin. “I need a refrigerator, I need an air conditioner and these things.” Then, whatever money I have, I request Alec to get something from Spokane or Seattle. Then the contractor says that the A/C will take two weeks to get there and then another week to fit it, so I say, “Okay, I’ll be here for ten years.” Then, I spend all the money, and it’s non-refundable, and then before the A/C actually arrives here, someone tells me, “Oh, tomorrow is your time to leave, the car is ready. You are just here for a few days.”

When I think that I’m really going to stay here for a prolonged period of time, then I’ll start planning. In the course of planning, if I ask Peter to do something and he says, “No, I have some other obligation,” then I get really agitated. Whereas if I ask Venerable Jampa to do something, and she enthusiastically does it then I feel so happy. So, there’s a sentiment of attachment or of aversion. In the course of planning, all these negative emotions arise, and because of these negative emotions, karma accumulates. These karmas will all eventually arise in the form of suffering. It will keep going in the form of chains of suffering, ripples of suffering.

So, the suffering has arisen by the karma which was accumulated by my negative emotions, such as dislike for Peter because of him not being considerate enough to do something for me, and a sense of liking for Venerable Jampa for doing things so efficiently. In the course of planning, I accumulate karma because of these negative emotions arising. And why do these negative emotions arise? Because of my misconception that I’m going to last here for a few months, for a few years, for the next ten years.

It’s because of this misconception that all negative emotions are given rise to, which in turn give rise to karmas, which in turn give rise to the next suffering in samsara. We eventually see that it’s rooted. But rooted to what? Rooted to my remaining here for ten years. Similarly, worse than that would be, “I will be eternally existent.” This is not just for a few years—eternally existent. I am permanent. This triggers all negative emotions. You would then tend to plan to live for a thousand years. You know that we’re not going to live for the next eighty years. Intellectually, we know that, but on the experience level, on the feeling level, we don’t agree with that. We think that we’re going to live for a thousand years, two thousand years—like that.

And, accordingly, we plan. It is because of this misconception that we feel so permanent, eternally existent. For example, I might expect myself to live for another forty, fifty, sixty years, but in a true sense, who knows? I might disappear from this world tomorrow, who knows? Some of you might be leaving tomorrow. We don’t know. It’s a fact. So, if you know this, and if you really reflect on it, and then integrate this on an emotional level, an experiential level, then we see that just as someone who knows I’ll be here just for a few days, I don’t even think of getting a refrigerator, or A/C, or these things for this small cabin. I’m not going to plan this, and because I don’t plan this, the afflictions which can potentially arise associated with planning will not be there. Because of that, karma is not accumulated, and I don’t have to experience the pain of this karma.

If you realize how transitory you are, then you don’t plan for the sake of yourself. But what about planning for the benefit of other sentient beings? Of course, do it! The bodhisattvas, when it comes to themselves, can simply reflect on the transitoriness of themselves. Whereas, when it comes to others—“others” is not just one individual person—one person goes, and then a second person will come, so you plan not just for one person but for the benefit of all the other beings bound to come. For the bodhisattvas, in terms of one’s self, you should be well aware of the transitoriness of one’s self. And in relation to other beings, you plan, you do everything. An example of this is Sravasti Abbey that Venerable Chodron is taking care of; this is how the bodhisattvas really should be doing. There is no qualm.

The basic foundation of Buddhism, the teaching of the Buddha, says that it is the first misconception, which thinks that you are permanent, that you are non-transitory, that you are eternal, which will then lead to planning for one’s self. Because of this, all afflictions, all delusions, attachment, aversion, and so forth, can arise. And the corresponding karmas are accumulated, which you have to account for in future lifetimes. Therefore, the First Seal says, “All composite things are impermanent.” In a true sense, as opposed to what we feel, the reality is that all composite things, including yourself, are impermanent, which means, “undergoes changes.” They are of the nature of transitoriness. And this impermanence has two levels, the gross level and the subtle level.

Gross impermanence

The gross level of impermanence is in terms of discontinuing the continuum. For example, the tree grows, and after ten years or a hundred years, the tree dies. It becomes dry, and then it’s over. There is a discontinuation of the tree after a hundred years or one thousand years. That discontinuation, a discontinuation of the continuum of a particular object, is what is known as the gross impermanence. For example, let’s say a child is born forty years ago and now is a middle aged man or woman, and then after ten, twenty, thirty more years, they are going to disappear from this earth. Say the person dies at the age of eighty or sixty; the person discontinues to remain as a person. So, there’s the discontinuation of the continuum of the person. This is what is known as gross impermanence.

When the Buddha says, “All composite things are of an impermanent nature,” we have to reflect on both the gross impermanence and the subtle impermanence. If we reflect on the gross impermanence first, then the subtle impermanence will make sense. And because of this, there will be a very strong desire, a strong urge, for the practice of Dharma.

First, we have to meditate on the grosser level of impermanence, which is our death, the death of ourselves. One day there is going to be our coming to an end. So then what will happen to you? Are you prepared for the next life? There are all these questions, right? Say a tree was planted in the year 1000, and now it is 2008, which means 1008 years have elapsed, so the tree is as old as 1008 years. Now it dries, and it is no longer green. So, a tree which lasted for 1008 years has now ceased to live as a fresh tree. This discontinuation of the continuum of this fresh tree is what is known as the grosser level of impermanence of the tree.

Now, in order to have that grosser level of impermanence, then it must be because of the presence of subtle impermanence. How? 1008 hundred years ago this tree was just a seedling, but now, not only has it grown into a gigantic sized tree, it has also dried. Now imagine this tree grew to the size of ten feet in 1000 years. It’s not as though for the last 1000 years the tree always remained as a seedling, and then today it all of a sudden grew to that size. Is this the case? No.

If it is a hundred feet tall, then for the last 1000 years, it grew from a seedling to a 1000-foot tall tree, which means that every ten years it grew one foot. Which means in a hundred years, it’s ten feet tall. In 1000 years, it’s a hundred feet tall. So, for one foot to grow, it took ten years. Is it the case that, for the last nine years and 364 days, it remained as a seedling and then all of a sudden the next day is going to be ten years, so it grew to one foot? No. Every year there is, say, one foot which you divide into ten pieces. The first piece took one year. It took one year to grow to that first foot. And then you go on like this. Then you see that the changes are happening within years, within months, within days, within hours, minutes, seconds, milliseconds. You can still go on like that. We see that change means that it’s not remaining static. If the changes are there from second to second, there are small divisions. Milliseconds are even smaller.

The change that the tree was undergoing is not like this a slow division. The changes are happening much faster. Similarly, our body, our mind, are changing quickly. If you really reflect with this logic, you try to shorten the length of the time, you try to break the length of the time into smaller and smaller pieces for its growth or for its maturation. Then we see that eventually, like some of the digital watches, minutes move at one speed. Then you imagine that in terms of seconds, it will move much faster. Then you break that into milliseconds, and it will go even faster yet. It becomes even more subtler with more divisions; I cannot even demonstrate it. [Laughter]

In a true sense, our body, our mind, our selves, everything is going at this pace. This is what is known as subtle impermanence. If you reflect on it so well, then a sense of fear arises in you. There’s nothing to hold onto as “I” or “self.” By the time you try to hold on to yourself as “I,” it already disintegrates into something else—that’s why this is a really very powerful meditation.

Say I feel so attached to this watch, so this attachment is primarily rooted to my misconception that it remains permanent and unchanging. But the reality is that, through the logic that I have given you, just as that tree is undergoing change, this watch also is undergoing change. Likewise, myself, the agent, is also undergoing this change. So, when you feel attached to it, this means that you would like to have it. You grasp the first moment you attach to that watch, but, by the time your hand reaches there, the first moment of the watch is no longer there.

This means that in a true sense, the reality is that it is impermanent. It makes no sense; it is totally contradictory to the reality of the watch and how our attachment looks at the watch. By the time your hand reaches there, what you really desire has already disintegrated. It is not there anymore. And likewise for the agent, yourself—you reach for the watch and put it under “your possession,” thinking that you’re permanent. You think you are the same person who thinks you’re going to get it and who already got it. You think that it’s the same person, but in a true sense, by the time you stretch your arms to get it, the person who wants to have that watch has also disintegrated. So, what’s the point? The impermanent agent is ignorant of the reality of one’s self and the watch, thinking that both the self and the watch exist as permanent, and then you try to get it. So, actually in terms of yourself as the agent, it also disintegrates by the time you reachfor it. And the watch also, what you really want to have, has also disintegrated.

The impermanent agent is wanting to have an impermanent object. This is the kind of logic put forth in Shantideva’s text. What sense is there when an impermanent agent wants to have an impermanent, transitory object? This attachment has no basis at all. Similarly, this needs to be extended to the second point, and third point, and so forth. This is how we need to reflect on the impermanent nature of all composite things, on the grosser level and on the subtle level.

But, of course, we need to know that in terms of the person, you cannot think of mind in general. We cannot think of the grosser level of impermanence, because a mind, in general, will never come to an end. There’s no discontinuation of the continuum of mind. Do we think the mind will come to an end? No—for the time being, no. It will never come to an end. It is Vaibhashika who believes that after achieving nirvana, when you die, the mind will annihilate. Otherwise, the Cittamatra and Madhyamaka—the two high schools—from their point of view, the mind always continues. Therefore, if you take the Madhyamaka into consideration, you can think of the subtle impermanence but not the gross impermanence.

If you come to know that all composite things are impermanent, what is there? Even Buddha Shakyamuni is also impermanent. But why should we feel so sad? Buddha Shakyamuni is also impermanent, but the thought of Buddha Shakyamuni has also delighted us. Even if you think about the subtle impermanence of Buddha Shakyamuni, there’s nothing that we should feel sad about. Then why should we when we meditate on this impermanence of composite things?

What kind of boss do we have?

The next point is “All contaminated things are of a suffering nature.” This statement leads to the next teaching. If all composite things are impermanent, simply don’t fantasize about yourself, the Buddha Shakyamuni and these things. Think of yourself as under a very kind boss. If you are under a very kind boss then you’re happy. And the boss leaves for holiday, and he is coming up in two days. The moment you think of him returning to work you feel more happy, thinking, “I have someone to complain to about all these things.”

Now imagine the boss is so cruel, and simply seeing you, he slaps you all the time. [laughter] Would you be happy? No. Say he goes away on holiday for two days. Would you be happy or unhappy? You would be so happy! [laughter] And then it’s just one hour before he’s coming back, would you be happy? No. You become sad. Similarly, if the boss is cruel and so bad, why are you unhappy? Because you know that you’re going to suffer under this boss. Whereas, if the boss goes away for good, would you be happy? Yes, you don’t have to be sad anymore because the boss has left you permanently. But, unfortunately, the boss is coming in one hour.

Similarly, we are impermanent, and impermanence means we undergo change. Change means changing by dependence on causes, and the causes are our bosses. The causes determine where you are going. If you eat good food, you will have a healthy body. If you eat poison, you are going to die. So, what you eat determines your next state. Similarly, the result is going to be determined by the cause. So, the causes are our bosses. In our case, we are in the state of transitoriness; we are in the state of change. Changing means we are determined by our causes. There is something which transforms into a result, which transforms into something else, so this result should necessarily be determined by the causes. So, what is the cause that determines our next destination in our case? It is our mental state.

The mental state is our boss which determines our next state. Is it virtuous or non virtuous? Is it kind or cruel? If our boss is kind, we will be so happy. Whereas, if that boss is unkind, so unruly, so harsh, so cruel, will you be happy? No. This means that if the boss is cruel, if our mental state is predominantly negative, what result are you going to expect? Pain.

All contaminated things have the nature of suffering

The second teaching is “All contaminated things are of suffering nature.” Contaminated means our minds are contaminated by delusions and give rise to a suffering nature. Whereas, if we were permanent, even if our mind was negative or deluded it would be fine, because in that case we’re not going to change into something else. So, if that were true, then we’re not under the power of our cause. But unfortunately, the first teaching says that all composite things are of an impermanent nature, which means we have to undergo change. This is our nature. It is not that the Buddha created it that way. It is our nature because we are composite.

If we are to undergo change, then what determines the next state? Change means going from an original state to a new state, so what is that new state going to be like? That is going to be determined by the first state, so what is that first state or what is that cause? What is that boss? This is, in our case, a contaminated mental state. So, as long as you are under a contaminated mental state, the result is going to give rise to suffering. All contaminated things are of the nature of suffering. This means that, because of our realization of impermanence, we come have a very clear picture of what we’re going towards. We’re going so fast towards what? We’re going towards suffering, because the causes that we are in contact with is something so defiled and contaminated.

We are going so fast towards suffering, but don’t be discouraged. The Buddha said that this is the reality that we are in; we should know about it. Unless you know you are sick, you won’t look for a cure. If you know that you are sick, then you look for a cure. Similarly, knowing the kind of plight that we are in, with no exceptions—every one of us is in this plight—once we know that, then what is the cure? Then the Buddha comes with the cure. It’s not that the Buddha only gives you the bad news; the Buddha also comes in with the good news. The good news is that there’s a cure for this sickness, this unbearable pain.

All phenomena are selfless and empty

The Buddha said that all these problems are created by this foolish thing called ignorance, which misconceives the reality, which views things totally incorrectly, totally contradictory to reality. The reality is that things simply come into being by interdependency. Things come into being by means of dependent origination. There is no absolute, independent nature. But this ignorance that resides in us so strongly, that is so well ingrained, thinks and views things to be existing as independently and inherently existent. This is the ignorance.

Because of this wrong perception, all this contamination and delusion has been in us. And because of these delusions, they give rise to ignorance and then propel you in this very fast paced state to suffering. What do you do to control something’s cause or boss? What is this boss? This is ignorance. So, you control that ignorance. You remove that ignorance, and then you’ll have a new boss. You’ll have the wisdom that, as your boss, is so compassionate, so nice, so kind to you, and who will not lead you to suffering. This state of impermanence, transitoriness, momentariness is just the same, and you don’t have to worry. It will not lead you off the precipice; it will lead you into a wonderful paradise.

You will know that the faster it is, the better it is for you, because the one who is leading you is so kind. It will lead you so fast into a land of paradise: nirvana, enlightenment. How do you deal with this ignorance, the cruel boss? It is by telling him that he’s not been kind, he has been deceiving us. How do we tell him that he has been deceiving us? “You have been deceiving us because you have been telling us that the reality is something else, but in a true sense, this is not the case. That reality is not independent. There is no independent reality. Everything exists in ways of interdependency, in ways of dependent origination.” When you get a very clear picture as to how everything is of the nature of emptiness and selflessness, as taught by the Buddha in the third statement of the teaching, then you come to know the reality. Once you discover the reality, then you will say no to the ignorance.

When you say no to the ignorance, this means you have to combat this ignorance, and surely you are going to win because you have a sound basis. You are being backed by the reality. You correspond to reality; you represent reality. Whereas, the ignorance is totally baseless. As you strengthen this realization of the reality, then ignorance will be eliminated. What will happen if the ignorance is eliminated?

Transcending sorrow is peace

The fourth teaching is, “Transcending sorrow is peace and ultimate virtue.” Eliminating this ignorance is the transcendence of sorrow. Once you eliminate the ignorance, once you transcend the ignorance, you will transcend sorrow, because all sorrow is based on this ignorance. When you eliminate the sorrow, then you achieve the ultimate peace and ultimate virtue, which is 100 percent happiness.

Ultimate peace and happiness is our goal. Our mission is accomplished. This is the basic foundation for someone seeking personal liberation as well as for someone seeking full enlightenment. This is common to both, but for someone particularly interested in full enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings, this needs to be a little bit elaborated, expanded. It’s the same teaching but a little bit expanded.

Bodhicitta and the Four Seals

So, you think about the first teaching, “All composite things are of impermanent nature,” but instead of simply thinking about yourself and the objects you feel attached to or aversion towards, think about the impermanent nature of all other sentient beings, and all the objects which create afflictions in other sentient beings. Meditate on the impermanent nature of all those things.

The second teaching states, “All contaminated things are of the suffering nature.” Here, you think about how other sentient beings are being tormented by suffering because of the ignorance and delusions present in them. Then the third one says, “Everything is of the nature of emptiness and selflessness.” Again, just as my knowledge of the emptiness helps me eliminate the ignorance, how I wish that all beings discover this fact that everything is of the nature of emptiness and selflessness, so that the ignorance in these beings as well will be eliminated. And what will happen if they discover this same thing? Then there’s going to be transcendence of sorrow, not only in you, but in all other sentient beings as well.

To be more courageous in expanding this mental reflection towards all other sentient beings, you must be motivated by a sense of genuine affection, a genuine closeness and compassion, towards all sentient beings. And to accomplish that is by the practice of the two techniques: the sevenfold cause and effect relationship to cultivate bodhicitta and the matter of equalizing and exchanging oneself and others to cultivate bodhicitta.

In a practical sense, in your daily life, whether you are at Sravasti Abbey or doing your daily job, one should lead a life of honesty. Always be honest. This will help you cultivate ethical discipline. And always be compassionate. This will help you nurture the seed of bodhicitta within yourself. This is what we can do even while we are engaged in our daily works; it is not necessary that you should be at the Abbey or at a monastery or a nunnery to practice these virtues. Even while you are doing your daily work, always be honest, truthful, and warmhearted.

Don’t give in to anger or hostility under any circumstance. Of course, there’s going to be instances where anger, hostility, and so forth can arise in you, but from your side, don’t ever give in to them. Even if it arises, you give yourself a chance in that moment to question if that is correct, and then you don’t say “yes” to those emotions. Simply say, “No, I’m wrong in having felt this.” If you realize, if you at least have said “No” to your own negative action of anger, this, in itself, is a great remedy to anger. If possible, try to make a commitment that henceforth you are not going to repeat this anger: “Henceforth, I’m not going to submit myself to this anger.”

Next time, when anger arises, again do the same thing, “No, no, no, no. I’m supposed to be a practitioner, and I’ve committed myself to not give in to the anger.” If you do give in to anger, tell yourself, “No, no, what a coward you are.” Tell yourself this, and make another commitment: “I’m not going to give into anger again. What a shame it would be to give into anger while I claim to be a practitioner.” Say this, and make another commitment that you are not going to give into anger again. You will see that over time anger diminishes in strength. When there is a situation when anger is arising, do you think there’s joy accompanying it? No. It’s a mental disturbance. So, when there’s the situation for anger to arise, but instead of anger arising there is a sense of joy instead, this is an indication of your success—your victory over anger!

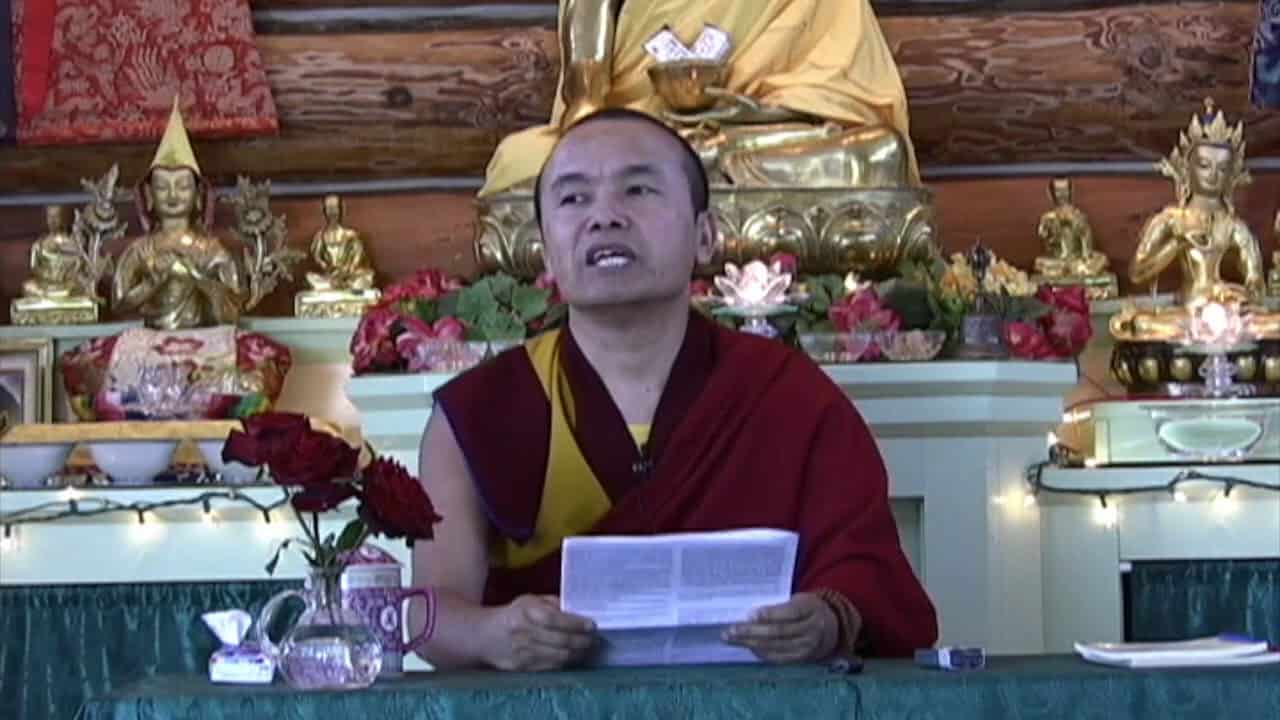

Geshe Dorji Damdul

Geshe Dorji Damdul is a distinguished Buddhist scholar whose interest lies in the relation between Buddhism and science, especially in physics. Geshe-la participated in several conferences on Buddhism and science, Mind and Life Institute meetings, and dialogues between His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama and Western scientists. He has been official translator to His Holiness the Dalai Lama since 2005 and is currently director of Tibet House, the Cultural Centre of H.H. the Dalai Lama, based in New Delhi, India. Geshe-la gives regular lectures at Tibet House and many universities and institutes. He travels widely within India and abroad to teach Buddhist philosophy, psychology, logic and practice.