Six harmonies in a sangha community

A talk given at Thösamling Institute, Sidpur, India.

Before we actually begin let’s take a moment and cultivate our motivation. Let’s think that we will listen and share the Dharma today so that we can identify and apply the antidotes to our mental afflictions and faults, so we can recognize and practice the methods to enhance our good qualities. Let’s do this with an awareness of how interdependent we are with other living beings, how we depend on the kindness of others to live and to practice the Dharma. Thus, as a way to repay their kindness we want to progress on the path to full enlightenment in order to be of the most effective benefit to all sentient beings. So take a moment and generate that motivation in your heart.

I am happy to be here again. I have taught at Thösamling a few times in the past. It is wonderful to watch the community here develop and to see so many nuns come here to train their minds and practice the Dharma. Venerable Sangmo has done a terrific job making this place come into existence and planning it. I hope all of you support her in her work and feel like this place is your own. I hope you feel committed to the Dharma and to developing the Dharma here, not just for yourself but also for all the future generations, for the people who will come here in the future to practice. We are setting up the Dharma for Westerners or for non-Tibetans, so we have to work together and cooperate. Everybody has to have a big mind and a long-term vision and think about all the people who are going to come after you, who are going to benefit.

Sometimes we are shortsighted in our practice and think only about what’s good for me. Where can I go to study? Where can I have a good situation to practice where the schedule is what I need, and the food suits me, and the people are nice to me, and I can learn what I want to learn. I want a place where I can meditate on love and compassion for all sentient beings when I want to meditate on love and compassion for them, a place where I can study the texts that interest me. I, I, I, me, me, me. I want to be in the most fantastic conducive place for my Dharma practice—for the benefit of all sentient beings!

It is so easy for us to get into a mental state that thinks only about my Dharma practice. We are used to that mental state because our whole life we have thought predominantly about, “Me, I, my, and mine!” Thus when we move into a Dharma center or a nunnery, we still think, “Me, I, my, and mine,” and expect everything to revolve around me. We don’t think about the repercussions of this self-centered way of thinking on the other people we live with, on the broader community around us, or on the rest of the world, let alone the repercussions of our self-centeredness on all the future generations of people who are going to come.

It is important to have a long-term vision that includes establishing a place that is conducive for Dharma practice and training our mind. Both of these activities will be of great benefit to future generations. How long are we going to live? A hundred years from now none of us will be here. But hopefully this place will be here. At that time, this place will have been imbued with the energy of people who have sincerely practiced the Dharma. Then in future lives we might be fortunate, have another human rebirth, and be able to come here and practice the Dharma. The conditions will be even better than they are now because the people who were here at the beginning worked so hard.

So let’s pull ourselves out of that mind that just thinks about my Dharma practice and think about the existence of the Dharma on this planet. It is not about my Dharma practice, it is not all about me. That I that keeps thinking, “My Dharma practice,” and “Good conditions for me!”—that I is the object to be negated in our meditation on emptiness. If our whole Dharma practice revolves around serving the dictates of that tyrannical I-grasping, then we have lost the point of the Dharma. Let’s soften the sense of I: there is no me here practicing the Dharma who needs the most wonderful conditions. There are just the aggregates, no independent me who is the owner or controller of this body and mind. Let’s do what is possible to enhance our good qualities and purify our mind while we have this opportunity, and to do it for the long- term benefit of all sentient beings. Forget about the I that clings to my enlightenment; and when I become a Buddha. Instead, consider the long-term benefit of all the generations of people who are going to follow.

I first came to Dharamsala in 1977, about thirty-two years ago. Since then so many people have come and gone. The opportunities that Westerners now have to practice depends upon what the people who were here before them did. We are much interrelated. Let’s carry that awareness when we practice.

The six harmonies: living in community with mindfulness

I was asked to talk about living in a community with mindfulness. The six harmonies that are spoken of in the Vinaya outline this perfectly. These are six ways of keeping harmony in the monastic community that help the community as a whole and help us as individuals. The purpose of being a monastic—of keeping the Vinaya, the monastic discipline—is to attain nirvana and in the Mahayana traditions specifically the non-abiding nirvana of a Buddha. A temporary goal is to create a community that facilitates the practice of the individual members, so that everybody can progress towards enlightenment.

The Buddha spoke about six harmonies that the members of a sangha community share. They enable us to fulfill the long-term benefit of enlightenment and the temporary benefit of creating a community that facilitates the practice of the individual members. I’ll list them and then will go back and explain them. Personally speaking, I always found this topic inspiring as well as helpful on a practical level. The six harmonies are:

- to be harmonious physically

- to be harmonious verbally

- to be harmonious mentally

- to be harmonious in the precepts that we keep

- to be harmonious in the views that we hold

- to be harmonious in how we share the requisites we receive

The first harmony: to be harmonious physically

Living together harmoniously physically is a respecting the physical well-being of other people—not physically harming other people in the community and taking care of each other. If somebody is sick, we take care of them. There is a story in the Vinaya about when the Buddha went to visit a group of monks and there was a quite a bad smell coming from somewhere. He went into that hut and there was a monk there who was ill and was lying in his own faeces. The Buddha asked him, “What is happening?” The monk said he was sick but nobody came to help. So the Buddha himself cleaned this monk and fed him. Then the Buddha told the other monastics, “You have to help each other. When somebody is sick, attend to him, and take care of him.” This is important when we live in a community. We all have human bodies, so our bodies go up and down and they have problems. Sometimes we have our agenda for what we want to do that day, and somebody else in the community is sick. Our self-centered mind think, “Couldn’t they get sick another day! It is so inconvenient today. I don’t want to take care of them because I was going to study this and do that, to go here and there. But now I can’t because someone is vomiting.” It is easy for us to have this thought, “It’s so inconvenient. I don’t want to take care of this person. Can’t somebody else take care of him? I have other important things to do, such as meditate on compassion!”

If we remember these harmonies, then we have to work with that mind that is saying, “It is inconvenient and I don’t want to.” Instead, we train our mind to see this as an incredible opportunity because just to live together with other monastics who are practicing the Dharma is a wonderful and rare opportunity. Thus caring for each other should be seen as a privilege. Especially if we are trying to develop love and compassion on the Mahayana path: to do something active to benefit other Dharma practitioners, let alone other sentient beings, is certainly within the scope of our practice. Sometimes we talk a lot about benefiting sentient beings, but when push comes to shove, sometimes Theravadins do a much better job than we do. But we go around with our nose in the air, “I am a Mahayana practitioner. I am aiming for full enlightenment, not the selfish enlightenment of the Hinayana!” That’s such a poor way of looking at things.

One time I was invited to a place to teach by a Tibetan center, but when I got there they didn’t want to pay the airfare. The monk at the Theravada center heard about the situation and offered the airfare. I was so surprised but it woke me up and made me think, “What love and compassion are we practicing? Are we doing it? Or is it just at the level of our mouth?” So this first harmony of living harmoniously together physically involves our mind as well as our body. So we take care of each other and respect people’s property, care about their well- being. We don’t hit them, beat them up, or do anything that would make them suffer physically.

The second harmony: to be harmonious verbally

Creating harmony verbally is more difficult than physically. I don’t anticipate people getting so upset in a monastery that they start chasing each other with a stick, slapping each other around, or beating each other. However, we easily use words to harm others. We have our own little arsenal of verbal weapons of mass destruction, don’t we? These weapons are located within our mind and cause great damage when used. They include saying just a few words exactly at the time we know will hurt somebody’s feelings. Sometimes we put somebody down, or make someone feel guilty, or denigrate a person—there are so many ways that we intentionally and unintentionally can harm people verbally.

Sometimes when we lack mindfulness, we do not have the motivation to harm someone, but other people misinterpret our words. But other times we intentionally deceive others by lying so that we look better or get something we want. Sometimes we cover up our own mistakes or blame others for them. We bad-mouth people behind their back, ridicule them to their face, gossip about them whenever we can. Wherever there is a group of people using our speech to create disharmony is easy to do. For example, we form a clique and gather together with our friends, saying, “So-and-so arrived late for morning meditation. They’re always doing that. How bad!” We get together with certain people and scapegoat someone or we speak badly about people in the Dharma community.

Careless or malevolent speech creates many bad feelings among people, and it makes it quite difficult to practice Dharma. Everyone in the community can easily become involved, thinking, “That person is criticizing my friend, so I have to defend my friends and attack my enemies.” We become very attached to our reputation, craving praise and not wanting blame. We become totally embroiled in the eight worldly concerns and Dharma practice goes out of the window, because we are all busy with harmful speech. We think that friends are people who side with us during a dispute, whether we are right or wrong. When we hear painful words, we want our friends to back us up to retaliate. In this way, we drag innocent people into the cesspool of our negative speech, our verbal weapons of mass destruction.

To abide in harmony verbally is especially important. This takes a lot of careful attention. It requires mindfulness on the part of the individual people in the community. Additionally, we have to set a positive tone for how we are going to live together as a group. At Sravasti Abbey, the monastery that I started in the States, we have weekly community meetings. We don’t use these to plan and organize events, but to talk about what has been going on in our minds and in our practice in the last week. We sit in a circle and each person talks, one at a time, sharing what he or she has been thinking about or feeling during the past week. This has been helpful to us for keeping harmony. We realize that we are all basically the same: we want happiness and not suffering. We see that each person in the community is doing his or her best, and we learn how to support them in doing this. We learn to acknowledge our faults and to admit when we haven’t followed the guidelines of the community.

Learning to acknowledge our mistakes is part of Dharma practice, and it’s important to do this not just when we do confession. Purification is not reserved to applying the four opponent powers at the end of the day, but to becoming more transparent in daily life. It is psychologically healthy to say, “I have done that, and I am sorry,” when we have gotten upset, haven’t been polite, or whatever. Who are we joking by denying our faults? In a community, we all live in close contact with each other, so everyone knows everyone else very well. We know each others’ talents as well as each other’s blunders and bad habits. So honestly acknowledging our faults is healthy and requires much less energy than denying our mistakes, especially when everyone else knows we made them.

When we live in community, we learn to ask for help. For example, many people come to me asking me to decide this or that. Some days, I’m full up to here. I can’t think about one more thing or make one more decision. So I say to people straightforwardly, “Please excuse me; I can’t make any more decisions. Please save it for tomorrow.” They understand and help me by taking some of the responsibilities. I trust the other people in the community well enough so that if I speak in a straightforward way, they will know that I need help. Developing the ability to communicate well with others—to apologize, to forgive, not to hold grudges—all these are so important for a harmonious community.

When the community is harmonious, it becomes so much easier for all of us to practice, because there isn’t energy going outwards wondering, “What do other people think of me? What is this person saying about me?” and so on. We can then use this energy for Dharma practice. A harmonious and supportive monastic community sets a good example for other people. This is important because people want to come to the Sangha and to the place of the Sangha for inspiration. If they come and see people who respect each other and help each other, they are inspired. But if they come and they see bickering, blaming, and quarrelling, they say, “Who needs the Sangha community? Why should we support them?” They are right. If we are not acting properly, then what is happening in our practice?

The third harmony: to be harmonious mentally

Conflicts arise and differences in opinion are natural. But having differences in opinion doesn’t mean that there has to be conflict. It’s strange how our mind thinks. Sometimes we think if somebody does things differently from the way I do them then we have to quarrel. “Those people have to think like I do because my ideas and opinions are correct!” When we investigate the reason why our ideas and opinions are correct, the only reason we can come up with is “Because they’re mine.” That is, we believe, “If I think it, it must be right.” What kind of logic is that?

That actually brings the third harmony, mental harmony. We think, “Everyone has to think exactly like me for us to be harmonious.” But where can we go in the whole world where somebody, even one person is going to think exactly like us in every way? We can’t find that place. And you know what? We don’t even think exactly in the same way we used to think a year ago. Have you ever thought about that? Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to meet the person I was in the past. What I would think about her? Would I like her or would I think she was rude, bossy, inconsiderate, and so forth?

Even within our own mind we don’t agree with ourselves all the time. We change and have different views. So of course with other people there will be differences of opinion. But having different opinions doesn’t have to mean conflict. When there are differences of opinion in a community, it gives us the opportunity to make a better decision, because when you hear everybody’s perspective you see things from a variety of sides, and that gives you the ability to form a more informed conclusion and to come to a better decision.

I try to learn from the Catholics, as well as from the Tibetans, in how to set up monasteries. In the rule of Saint Benedict, Benedict was quite clear that everybody in the community should have the opportunity to offer their ideas. However, not everybody makes the decisions. The Buddha set it up this way too. The seniors (the people who are fully ordained or in the case of a community of novices, the senior novices) make the decisions because they have been around longer, and they understand the Vinaya better. They understand what a monastic mind is like better. But the decisions that are made by those people should be informed by everyone’s perspectives. This is because sometimes the people who are brand new might have a good idea that everybody else doesn’t see. But the decision-making power doesn’t belong to everybody in the community—because the people who are new don’t know the Vinaya well or they don’t know the Dharma well. So it’s not beneficial for the community if everyone has an equal vote or say in all the decisions. The juniors have to trust of the seniors in making decisions because it takes time to learn how to be a monastic, and the seniors must practice well and be worthy of that trust. It isn’t that we just put on robes and shave our head and we know what it means to be a monastic. Especially the first year of your ordained life, it’s crucial to be with senior monastics and teachers and to live with a community.

Actually that’s why the Buddha set it up so that for the first five years new bhikshus and bhikshunis must stay with the community and with their teacher. If this applies to those who are fully ordained, it is even more important for sramaneras and sramanerikas, who are novices. In the ordination ceremony, there is a part where you actively take dependence upon your preceptor. Taking dependence means you say to that person, “Please train me!” You are voluntarily offering yourself to be trained, knowing that you can trust the wisdom and skill of somebody who is senior to you, such as your preceptor, to train you. This involves giving up our own “know it all” mind and trusting the seniors who have studied and practiced longer than we have. When we first ordain, we don’t know what we are doing. Some people make it through the first year and then think, “Well, I have made it one year. I know all about being a nun.” No! Many times, when we haven’t had a good situation around us, we have developed many bad habits in that first year because we haven’t been near our own teacher, we haven’t been in a community, or we haven’t wanted to listen to seniors. But because we made it one year alone as a monastic, we thank that our bad habits are good ones and that we know what we are doing. And that is not it! This training process in the sangha community is quite important.

To benefit those of you who are new in your ordination: you are so fortunate to have seniors that speak English. When I ordained, the only Westerners that had been ordained longer than me were only one to three years senior to me in ordination. The other examples I had were the Tibetan nuns. But thirty years ago the Tibetan nuns didn’t have much of an education. They were quite shy. So it was difficult to find senior nuns that I could rely on to help and guide me. This is the beauty that you’ll find in the traditions where there are bhikshunis: Korea, China, Vietnam, and so on. There are many people who have been around for a number of years and who have trained well. If you are near them, you receive the benefit of seeing how they act and how they do things. Especially if you have trust in the teacher and in your seniors, then they know they can actively tell you things even when a situation is happening. That can be helpful in your practice.

But we have to have the mind that is willing to be admonished. That is a hard one for Westerners, we don’t like to be admonished, we don’t like our faults pointed out. We like to point out other people’s faults, we are good at that. But we don’t like other people to point out things about us. But this is what training is about. We need to allow that to happen and to welcome it, knowing that it is for our own benefit. At the Abbey, I will sometimes point something out to someone while the situation is happening or just afterwards. That can be very effective in our training because our affliction is right there and we are acting under its influence. This way we learn to stop and think, “That’s true, how am I speaking to this person?” So it can be helpful.

Sometimes somebody talks to you later on because they see that right there in the moment you are not going to be open, you aren’t hearing anything. So they come to your room later on and say, “I was listening to how you were talking to so-and-so, and it seems that you weren’t happy.” They then give you the chance to talk about what was going on. In this way, we learn how to apply the Dharma to our daily life. But we have to be willing to have things pointed out to our. Our instant instinct is to get defensive, “No, what are you talking about? I am not doing that. I am not angry. I am not stressed. Just mind your own business. I just got done meditating on compassion. I am perfectly calm and talking to everybody nicely.”

Sometimes our mind is resistant, and we have to be careful. In that case, others have to be particularly skillful and talk to us at the time when we are going to be a little bit more open. Having the same Dharma goals and helping each other actualize them is mental harmony.

Mental harmony also involves appreciating and supporting each other. If we do that, community life goes better and our individual practice goes better too. One time one of my teachers said (because we sit in ordination order), “You sit there and look up at the row and think, ‘This person has this fault” and you look down the row and think, “That person has that fault.” In other words, no matter whether someone is junior or senior to us, we pick faults with them all! We go on and on, mentally listing others’ faults and defects. If we want to see faults, we’ll see them. Whether they exist or not is another question, but when our mind wants to see faults it definitely can find some to see, or it will fabricate some. But when we do that to each other, especially in a community, we’re unhappy and we make our relationships with others very sour.

Whereas if we train our mind to look up the row and think, “That person does this well, and this person does that well, and this one is good at this.” We look down the row, “This one has that talent, that one is sincere in this area, and this one is excellent in that.” When we train our mind to see peoples’ good qualities, there is much more harmony in the community and as individuals, we feel happier.

Living in community is an important practice for generating bodhicitta. If we think that we are going to our room, lock everybody out and then meditate to generate bodhicitta, forget it! It is easy to see peoples’ good qualities when you lock yourself in your room and you don’t see anyone. But the real thing is to actively notice peoples’ good qualities when you are with them, to train your mind to see their good qualities, and to train your mouth to speak about them.

After my teacher spoke about looking up and down the row of sangha and pointing about everyone’s faults, I realized that I had some work to do because I was good at finding peoples’ faults. Some years later, a group of international nuns was in Bodhgaya. I realized at that time that I was able to look up the row and see the good qualities of those nuns. Previously, I had criticized many of them. I had been jealous of their good qualities. I had been jealous of the people who spoke Tibetan, I had been jealous of the people who got to do retreat. Whatever somebody else did that I wasn’t able to do, I had been jealous of—even when they created virtue! This was not a good state of mind. So I was pleased to see that by working at it and training my mind, my mind had changed so I felt happy at others’ good qualities and could rejoice in their virtue, rejoice at their opportunity to practice, rejoice in their knowledge, rejoice in their study. It’s so much nice to appreciate others than to criticize them!

Training ourselves to rejoice at the good qualities of people in the community and to appreciate them is the preliminary for training ourselves to do that with all sentient beings. The people we live with in the sangha community are making an effort to be good people. They are trying hard. All sentient beings aren’t necessarily making that effort. We’ve got to start with the people who are making that effort, it will definitely be easier to see their good qualities. Then from there, we extend it to all other sentient beings who don’t know anything about Dharma and who sometimes are totally overwhelmed by their afflictions. Practicing like this is involved in creating mental harmony.

When I went to Taiwan to receive the bhikshuni vows—there is a one-month program in which they train you and give the sramanerika, bhikshuni, and bodhisattva vows. There were 550 monastics and two of us were Westerners. We didn’t speak either Mandarin or Taiwanese, which were the main languages there. I was wearing Chinese robes, which I had never worn before, and I find it hard enough with Tibetan robes, keeping them straight and looking nice. The Chinese nuns would walk by and my hands would be like this (pointing out) and your hands were supposed to be like this (pointing upwards), so they would move my hands into the correct position. When you walk into the meditation hall you are in line and walk with your eyes down. But I wanted to look around and check out what was going on around me. The seniors had to remind me, “Keep eyes down, you are being humble.” Then there was my collar—try taking an ex-hippy and making it so that her collar is always nice and her clothes tidy! The senior bhikshunis continually came to me when we were standing in line to straighten my collar and robes. Initially one part of my mind thought, “I am not four years old! I know how to put my clothes on!” But then I realised, “They are doing this for my benefit, to help me be more mindful, and to help me learn to be more humble.” My ego had to let go of its trip. That was a good practice for me.

The fourth harmony: to be harmonious in the precepts

The fourth one is harmony in the precepts: we observe the same precepts and guidelines. We have the pratimoksha precepts, we follow the same ones even if we are in a community where some people are fully ordained and some people are novices. The purpose of being a novice is to train yourself in the vows of somebody who is fully ordained without yet having taken all of those precepts. In a sangha community, everybody is training in the same way. You follow the precepts as well as other Vinaya guideline. In addition, we all follow the rules or guidelines of that particular community—each community will have different guidelines, different rules, different ways of doing things—and we should respect and follow those as well. In a sangha community, we can’t just do our own trip, doing what we feel like doing when we feel like doing it. Instead, we’re training ourselves to go beyond that self- centeredness.

It’s not wise to enter a community and say, “Well, my teacher says it’s okay to do things this way,” which is a different way than how the community is doing it. We don’t do that! We are coming in to be part of the community and to be trained. We don’t come in waving our own flag saying, “My teacher let’s us do this and that so I am not going to follow the rules of this community.” That doesn’t make for much harmony. It is important to follow the community’s guidelines.

When we come into a community, we may want to redesign the guidelines so that they suit us. I have talked with some Catholics and they say that there are three things that are continually the topics of discussion that everybody wants to alter. The first is the liturgy—the prayers, recitations, and practice that the community does together aloud. The second is the daily schedule. The third is food, the kitchen. It’s the same in Catholic and Buddhist communities: people are dissatisfied with and want to change the public prayers and practices, the daily schedule, and the food. Someone new joins the community and before long they’re saying, “Why do we recite refuge three times at the beginning of each practice. Isn’t once enough?” Plus “The chanting is too slow,” and “Why do we have to meditate for an hour? I want to meditate for 45 minutes and then do prostrations.” Then, “The schedule says that we start meditation at six o’clock, but I want to start at 6:15. So I think we should change the schedule.” Then, “Why do we have rice every other day? Let’s have more noodles. And by the way, we need more protein. Plus, the spices aren’t added correctly.” When you are new in a community those are not your decisions to make. You are coming into the community to be trained. The schedule has been set up by seniors who have more experience and do things in a certain way for specific reasons. In addition, all our complaints center on the eight worldly concerns. They come down to the basic principle by which we live our samsaric life, “I want what I want when I want it.” Isn’t this the mind we are trying to free ourselves from? So when we come into a community, we follow the ways things are done without complaining and wanting to change them all.

Now of course if there is something that contradicts the Vinaya, you can go to one of the seniors, comment on it, and suggest a change. There are all sorts of small Vinaya points that are done for particular purposes that can be quite helpful.

I tell people who want to come live at Sravasti Abbey, “No one like the way the practices are arranged in the meditation hall. No one is happy with schedule. Everyone thinks the food needs to be improved. And you know what? Even if we changed the schedule, not everyone would be happy with it. Even if you were able to be abbess for the day and make the daily schedule the way you wanted it to be, you’re still not going to happy about it. So just know that and be prepared. You’re not alone.”

From day to day we want something different, don’t we? One day we don’t want the meditation at 6:00, one day we want it at 5:30. The next day we want it to be at 6:15. One day we want the meditation to be longer; the next day we wanted it to be shorter. One day we want to do prostrations before meditation, next day we want to do prostrations afterwards. Our mind is so changeable and fickle. Just know that you are never going to be satisfied with the prayers that are recited. They are always going to be too slow or too fast. Or the chant leader is going to chant too high, or they are going to start too low. Because why? Look at our mind: how often are we satisfied with anything? Our mind always wants to tweak everything to make it the way we want it to be, we are always complaining about something. So we might as well get used to that and know that our self-centered thought will not be happy in the monastery. But isn’t it precisely this self-centered thought that is our enemy? Isn’t getting rid of it and the eight worldly concerns our reason to ordain?

Basically what I am saying is the problem is not the structure, the problem is our mind. For example, at the Abbey, we do some chanting after lunch. We do the preta offering and the dedication for our benefactors, and then we also chant another text: the Heart Sutra, or the Three Principal Aspects of the Path, or the Thirty-seven Practices of Bodhisattvas. People take turns leading the chanting, and some people chant too high for me, I can’t chant that high. But when they start lower, it’s too low for another person. We never get it right for everyone, so let’s give up. When it’s too high for me, I just whisper the verses without interfering with their chanting. They are doing it in a certain speed, so I just give up and do it at their speed. Sometimes they are doing it too slow, too fast.

We train ourselves to follow the guidelines of the community instead of saying, “But I want things done like this. I want to change the rules.” All of us practice following the same rules and precepts. This is being in harmony due to keeping the same precepts and guidelines.

This brings a real peace in the community, and that’s an important way to support each other. Let’s face it, individually would we be able to keep our precepts as well as we do when we live in a community? Individually, would we always be up every single morning without fail to meditate? There are a few people who are self-disciplined. But most people, “Oh, I am tired tonight. I am not going to meditate.” Or, “I’ll do my meditations,” but they press the snooze button on the alarm clock. When you live in a community, because we all follow the schedule together, then everybody does the same thing at the same time. Instead of sleeping in, we get up. The amazing thing is that you often discover that you can function on less sleep than you thought you needed. Whereas if we are left on our own, we obsess, “Oh, I have got to have so many hours of sleep, otherwise I just don’t function.” We get rigid.

But we live in a community, we adjust and do what everyone else is doing and in the process, we discover that we can function just fine with fifteen minutes less sleep. Everybody doing the same things at the same time is so beneficial for our own energy. It makes it easy to practice because the schedule is set up for Dharma study and practice. Everyone helps everyone else by keeping the schedule.

The fifth harmony: to be harmonious in views

The fifth is harmony in views, which means having the same world view. It doesn’t mean having the same political view or the same view on social issues. We are training our mind in the Buddhist world view, and one important aspect of this is that our happiness and suffering come from our mind. They don’t come from outside; they don’t come from objectively existing people and things because such inherently existent things do not exist. One way our mind creates our happiness and suffering has to do with karma. Our afflictions create negative karma, which brings the result of suffering. Virtuous mental factors create constructive karma, which brings the result of happiness. Another way that our minds create our happiness and suffering is by means of how we interpret events. When we look at things from a narrow, selfish viewpoint, we are miserable. When we look at the same situation and practice thought training, we are happy.

Everyone in the sangha is training in the Buddhist view. Everybody is working on realizing that we are stuck in samara and that we are all under the influence of ignorance and karma. All of us want to get out of samsara and to help others get out as well and we know that mental transformation through Dharma practice is the means to do that. In other words, we share that world view of the Four Noble Truths.

We are all training our mind to think that future lives are more important than this life. This is another view we have in common. Instead of just looking out for the benefit of this life, we try to help each other create the causes for happiness in future lives. We share the view that liberation is possible through eliminating ignorance, afflictions, and karma. We share the view that enlightenment is possible though developing bodhicitta and wisdom realizing emptiness. We accept that there is rebirth and multiple lifetimes; we accept that our actions have an ethical dimension and that our actions bring results now and in future lives.

Sharing these views helps us in our communal practice. It changes the dynamic of how we function together as a community. When we make decisions, we do not make them from the viewpoint of what’s going to benefit us in this life. We make decisions from the viewpoint of what will benefit the existence of the Dharma in this world, what will facilitate the enlightenment of all sentient beings, and what will enable us to abandon non-virtue and create virtue. Community decisions are made from a viewpoint that is quite different from the usual societal, worldly criteria. We share these views and train ourselves in these views, and this supports our practice.

Now the question comes up, “Does that mean that everybody in the community believes in rebirth?” Some of us may have a deeper understanding of rebirth and a deeper conviction in it. Other people may not have such a deep conviction and may put it on the backburner, so to speak, so that they can learn more about the Dharma and take the time to develop an understanding of rebirth. But we still keep to the general view that rebirth exists even if we ourselves personally are 100% convinced and don’t have a strong feeling for it yet.

In other words, we don’t negate things that the Buddha taught. I say this because in the West, even amongst Buddhist teachers, you find those who do not understand or agree with something the Buddha clearly taught and so they say, “The Buddha didn’t teach this.” Rebirth is an excellent example of this. It is clear in both the Pali suttas and the Sanskrit sutras that the Buddha taught rebirth. If you don’t have strong conviction in this, don’t force yourself to believe it, but think,”I will train my mind and think about it. In that way, slowly I will come to an understanding.” Don’t enter the sangha and then say in a hostile, sceptical way, “You can’t prove there is rebirth. It doesn’t exist. This isn’t the Buddha’s teaching. You should follow the view I have which is xyz.” Doing this is what is called abandoning the Dharma. Abandoning the Dharma isn’t just quitting your practice. It’s abandoning the teachings that the Buddha gave, teaching something that the Buddha didn’t teach, and saying this is the Dharma. So that’s something very detrimental to do. So maintaining harmony in our views gives us a lot of strength, energy, and support.

The sixth harmony: to be harmonious in welfare

The last harmony is to be harmonious in welfare, which means the community shares the requisites together. This is a practical issue and involves the distribution and use of the four requisite—shelter, food, clothing, and medicine. It involves how we handle donations and offerings to the sangha. In the Chinese, Thai, and Korean monasteries, members of the community share things quite equally. This means there is not a “class” of rich monastics, but everyone shares the resources and requisites equally. Offerings are distributed equally, and sangha members all have the same level of living standard.

Unfortunately, you don’t necessarily find this in the Tibetan monasteries. Even in old Tibet—pre-1959—there were different economic classes of monastics. If you read Geshe Rabten’s autobiography, it’s clear. He was very poor and often didn’t have enough to eat. Then there were other monks who had a lot to eat. We see the discrepancy now in the Tibetan monasteries too. In southern India, the monastics who have private sponsors often build their own house, which is considerably nicer than the standard accommodation. Khamtsens with lamas abroad who send back donations have nicer living quarters than khamtsens that don’t. We see the discrepancy in the Western monastics: some people have money. They can travel around, and go to all of His Holiness’s teachings. They can do retreat when they want to, go to this teaching and that teaching. They can buy air tickets easily, pay for hotels when required to attend a teaching, and so forth. Meanwhile, other Western monastics have very little money. They stay in the Dharma center and work while others are off attending teachings or doing retreat. I don’t think that that’s the best way to do things. In the early years, I was one of the poor sangha who had very little money, so I know what it’s like. Sometimes I couldn’t attend teachings because Dharma centers charged sangha and I didn’t have the money. I don’t think it’s good for Dharma centers to charge the sangha and hope that as centers realize the benefit of having sangha, they will stop doing that. That’s why in setting up Sravasti Abbey, I did it differently. We share the resources equally and so can attend teachings and do retreat equally.

I think it works much better when we are economically equal and share the four requisites. This entails that people are stable members of a community. Here in India, it is different because people come and go, you have visa problems, it isn’t your own country. People are not going to live in India their whole lives. Nevertheless, as much as people can help each other out and live at the same standard, that much it promotes harmony and goodness.

I say this not only because of my personal situation, but also because of the effect it has on monastics who have a lot of personal money. They missed out on a lot of training. For example, when something happened in the community that didn’t suit them, they moved somewhere else. They had the money to do that. They didn’t take the opportunity of working through difficulties because it was so easy to think, “Oh well, I don’t like this place. I’m going to the next place.” When we can do what we like because we’re not a member of a community and have the finances to travel, then we go to the next teaching, go to the next retreat, and miss the opportunity to grow through sticking it out through difficulties. When we live as guests in a community, not as actual members, then we miss out on the training that comes through being responsible for the sustenance and growth of the community and the welfare of its members. When we live as a guest, we are absolved from a lot of responsibility and so we miss out on that aspect of the training. However, when we see ourselves as, “I am a member of this community and I am committed to this community,” your mind changes and you look beyond what conditions are good for your own Dharma practice. You look beyond what is suitable for you and what you feel like doing. Instead, you look out for everybody you are living with. You have the sense of preparing the monastery for future generations of monastics who are going to come.

So that’s a little bit about the six harmonies: physical harmony, verbal harmony, mental harmony, harmony in our precepts, harmony in our views, and harmony in the requisites. Please ask questions and make comments now if you like.

Question: Some of the people who come to Thosamling have had good experiences living in Dharma centers and others have not, i.e. they were forced to say things in community meetings and thus do not now feel comfortable in them. Some want to focus only on their studies, others are more interested in building community. Personally, I like the idea of coming together as a community and talking so that when people come from outside they will feel the warmth in the community and will be encouraged by that. It is my own feeling that it would be beneficial, but others are not as interested. Do you have any ideas?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: People may have had bad experiences in community meetings at Dharma centers in the past because those meeting were not run skillfully. At the Abbey, we make sure that we talk about ourselves. We don’t point the finger at others in a blaming way, although we may talk about how we felt when someone said or did something.

One time, a young man came to visit the Abbey. It happened that we needed to gather together to discuss something, and this person kept saying, “You!” He would say, “You think xyz and you’re doing xyz and things would be better if you did abc.” or “Why don’t you do that?” I had to keep reminding him, “Here we speak about ourselves. Please don’t tell us about our own minds, please tell us about your mind. Please don’t tell us about what we are feeling or thinking, please tell us what you are feeling or thinking.” You need a facilitator who pays attention to this and who everybody in the group respects when they say, “Excuse me, but that’s not the topic. We are not talking about somebody else not cleaning up the kitchen. We are not talking about someone else’s biases. We are talking about our own.”

In community meetings, we talk about our own feelings and experiences to the extent we feel comfortable. Nobody forces someone else to open up more than they wish to. For example, instead of blaming someone else, someone may say, “I went in the kitchen and things weren’t put away properly. I got angry, and my anger is my problem.” Then the point is, “I got angry and my anger is my problem. I am just expressing that so people know that I get angry at these things and I am owning that’s my problem.” Sometimes the discussion later involves into talking about how the clean up of the kitchen is done.

The weather at the Abbey is four distinct seasons, and this influences what work we do when. So in the summer the person in charge of the forest will say, “I need more people to help me this week, because I am alone and all the work that needs to be done isn’t getting done. Can I have some help?” The whole community usually respond, “Yes, how can we help?”

But I think the real key is everybody talking about themselves and not pointing fingers, “You are doing this,” or “You are feeling like that,” or, “You are thinking this.” Some people may not feel so comfortable, so they don’t say much. That’s okay. Just leave people be, let people speak at their own comfort level. Gradually as trust develops, people will feel more comfortable talking about other things.

Dedication

Let’s dedicate the merit that we created as individuals and as a group for the existence of the Dharma in our hearts and in the world forever, for the long life of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and our other spiritual mentors. Let’s dedicate for peace in the hearts of sentient beings and in their environment and for the enlightenment of all living beings.

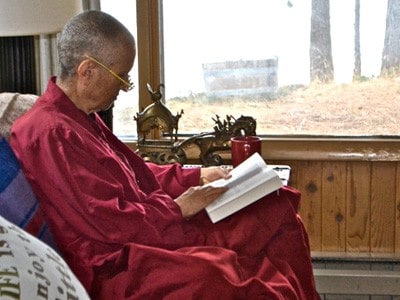

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.