Physical prison versus samsaric prison

Part of a series of teachings given at the Winter Retreat from January to April 2005 at Sravasti Abbey.

Here we are again—two thirds of the way through the retreat. It’s incredible, isn’t it—hasn’t it gone quickly? One of the things that is apparent to me is the harmony in the group—all of you. Barbara noticed too, how much people take care of each other and how sensitive and caring you are with each other. I think that makes a huge difference in how the retreat goes for everybody—for you, the people serving it and for me. It’s quite remarkable. I’ve been reading some of the sutras in the Pali cannon and in one of them the Buddha goes to visit Venerable Anaratna and two other monks. He noticed how harmonious they were and he asked them, “What are you doing that you are so harmonious?” Venerable Anaratna said, “I consider it a very great privilege to be here with these other people and to be able to practice. They are so much support and help to me.” The other monks felt similarly. Whenever they went out on their alms round, whoever came back first set things up for the others and whoever came back last cleaned up, and when a water jug was empty whoever saw it, filled it and if he needed help and asked for help, somebody gave help. Somehow people were just really cooperative. Actually something in the monastic community that is very important is called the Six Factors for Harmony and this is what Venerable Anaratna mentioned:

- Physical harmony—doing kind actions to the people who you live with physically.

- Verbal harmony—speaking kindly to them.

- Mental harmony—appreciating them and having kind loving thoughts about them.

- Harmony or equality in the virtues or precepts that they kept. Here at the retreat, applying to our situation, you’re all keeping the Five Precepts. Some of you are keeping the Eight Precepts, for two weeks you all were keeping the Eight Precepts—harmony in your precepts.

- Harmony in your views—the views that you have about the Dharma and sharing that.

- Harmony in sharing your requisites—all the food, clothes, the different things people share amongst each other. Nobody keeps a big stash of the best stuff in their own room—or if you are you’re doing a real good job of hiding it. That kind of thing creates jealousy and so on.

You can really see that when each individual feels that gratitude for the group and acts accordingly, it creates such a nice ambiance for practice. I really want to congratulate all of you in what you’ve done because it’s really very, very nice.

A letter from Lama Zopa Rinpoche

Another thing that is quite nice is that I received two postcards from Lama Zopa Rinpoche; which is kind of extraordinary because he doesn’t write—at least to me. I’ll just read you a few parts of what he wrote.

“My very dear Chodron, I was very happy to visit. I think the spot you chose for the Abbey is wonderful—a place for awakening! It seems you lead with the practices from sutra, so that is very, very good—community practice. Of course, later on, people take Bodhisattva vows and enter tantra, etc. and there are other prayers that have deeper benefit. As Westerners they might not like so much gatherings and prayers [he means, the community, doing things together]. Other traditions, like the Chinese have a very strong tradition of prayers in group—this is very good and powerful; helps every one together to collect merit and purify. It is mentioned in the Kadampa teachings [I’m going to paraphrase because the English here wasn’t too good] between doing prayers in your room alone and in community, it’s a hundred times more powerful doing the prayers and practices together in community. So I was very happy to see those group practices and group discipline”.

“Regarding the Heart Sutra, with the Chinese the tune is better than ‘blah, blah’ in English. I remember His Holiness the Dalai Lama asking you and others to chant. [This was in 2002 when His Holiness was teaching in Los Angeles, the different Buddhist traditions would come up and chant the Heart Sutra, the Theravadan’s did some other sutra chanting. On the last day, English speakers came up but we couldn’t chant, we just read it. Rinpoche remembered that, and so he’s very happy now that we have a chant, with the Chinese tune—that’s the wooden fish [percussion instrument used to keep the pace when chanting]—that’s much better than blah, blah reading in English.] There were other cultures chanting also at that time [in the year 2002]. I think it would be good to develop chanting for English. I am sure that can be done—my suggestion! If it is difficult to make English chanting then you can do Tibetan tunes in English, but it would be better to develop English chanting [I think he means English melodies]. You did the mantra of the Heart Sutra very nicely, so you know how to do it. This is just my thought, an idea.”

That was nice, wasn’t it? [Referring to the above postcard.] I thought you would like that and your chanting clearly made an impression, I thought especially with the Mandala Offering.

Appropriate use of food at the Abbey

Speaking of sharing requisites, one of the harmonies—this morning I did a little tally of what there was out for breakfast: seven different juices and milk to drink, plus the teas and water. Mind you, there are ten people. There were five different kinds of cereal, different kinds of yogurt, fruit; three kinds of bread (usually there are four or five); two kinds of cheese, peanut butter, eggs and other things. [some laughter]. I’ve been wondering for several weeks whether I need to say something about this or not. Because those of you who live here (Nerea and Nancy) know that I am constantly emphasizing that this is a monastery, where we practice simplicity. We are not a retreat center or hotel, where we have extravagant things for people. During precept time, I didn’t say anything. I thought well, they are only having two meals a day (and I know some of you are still doing that—and it’s wonderful, those of you who are keeping precepts for a long time, it’s really, really wonderful, thank you.). But I wonder if we need to be… if there were only two kinds of cereal out and it wasn’t your favorite and you had to eat another kind of cereal, I’m wondering if it would cause incredible hardship in your meditation? [laughter]. I’m wondering… it was interesting… when we all did precepts—there were 5-6 bottles of juice downstairs. I had different ones at different times… they all tasted the same because they’re all sugar water. So I am wondering if we need so many kinds of sugar water out, or if maybe one or two would be sufficient. Susan is doing a marvelous job with the meals and I am concerned that the people who live here permanently are going to get spoiled; because normally we don’t eat like this; normally, there is one grain or pasta, one vegetable and protein and salad… that’s what we have. Susan’s doing this incredible job; and I told her not to change that. But, on top of that, do we need half of the refrigerator out on the counter? [laughter]. Maybe people could manage with a quarter of the refrigerator? I am just wondering about that.

And I am wondering, what mental state is this coming from? I am not talking about cutting down on the quality of the food; or changes for people who have different health (allergy) needs. Of course, that’s going to work; we wouldn’t cut that out. But I am wondering what mental state is feeding this action of filling the kitchen with such a diversity of choices? And I am sure not all the things get used each day, because there are only 10 of us here. So, I thought I would put that out for the group to think about… what mind state is feeding your relationship to food during the retreat? And then just consider that it might be something useful for you to practice with in only having two choices of cereal, or two choices of drinks?

Then another thing, I know some of the people who are doing precepts (and again, it’s fantastic that you are doing that)… but do you think, well, “I am only having two meals a day, so the rest of the time, I can load up on sugar.” There’s candy and chocolate and sugar water under the name of fruit juice and all this other stuff. And again, what mind is that coming from; that sugar is going to make me happy? In our lunch verses, we say, “By contemplating this food as wondrous medicine to nourish my body…” Is sugar wondrous medicine to nourish our bodies? Now, I have a sweet tooth too, so I am not advocating the abolishment of all sugar. But I am saying maybe, on an individual level, we need to practice a little bit of restraint here. Especially when we say, by contemplating this food as medicine, I will consume it without attachment or hatred—attachment meaning, oh I want it and hatred meaning, yuck, I don’t like it.

How are we practicing in regards to food; are we substituting sugar as a comfort food when we are skipping a meal? And what does that do our body and our health? And what does it do to our ability to function smoothly, because you get a sugar high and afterwards, you are very lethargic. So you get this high on sugar and go into the meditation session or sit to read a book or something else and you are lethargic afterwards. Because that’s how your body metabolizes sugar, you get active and then like this [she gestures downward]. So, we need to see our bodies as precious vessels that we need, to practice the Dharma and so we need to eat in a very healthy way. And due to Susan’s [the cook] kindness, we’re eating incredibly healthy. Again at the Abbey we usually don’t eat so much organic food, it’s quite expensive. We don’t have that much organic, we don’t have that diversity and so on. So, this is just something to think about in your practice; to think about your health and how to really keep your body healthy for your own benefit and for the benefit of all beings. Ok? So, we can all have chocolate at the end… no I’m joking [laughs]. Like I said, I’m not advocating eliminating everything, but just to look what is happening.

Ok, what was next on my list? Did anyone have a comment about that? About anything so far?

Susan: I appreciate what you’re sharing and what is difficult for me to know is that I think I’m the one putting out the food. So I make those decisions I’m not clear what that means.

VTC: Ok, how should we do this? Because it does put the burden on Susan because she is the one who sets up, for what to put out and what not to put out.

Nanc: The food might be able to go through a cycle. One morning we have hot cereal, some fruit and maybe some protein source and the next maybe bread and cereal? Maybe it cycles around, because I know that Susan, is responding to the amount of food that we’re… I mean the appetites that come to the breakfast table are pretty hardy, especially with the precepts. For me, I know my appetite is hardy in the morning so I think you’re (Susan) responding to that. It’s your response to wanting to feed us.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Or, because some people like cereal and some people like bread, or if we had all of that out, but maybe we only have one kind of bread and two kinds of cereal, the fruit basket is there, everybody can take what they want. You know?

Aida: Venerable Chodron, one problem with the bread for example is that one of us needs the whole wheat bread, but for the vegan people that doesn’t work—they need another kind of bread. So if there is only one kind it doesn’t work for both.

VTC: Ok, what if we had two kinds of bread rather than three or four? How would that work? One that works for the vegans and one that works for the whole wheat people? And then instead of having the rice dream, milk and all the varieties of soy milk, if we just have soy or rice milk, plus regular milk—just two kinds? And maybe two juices, you know? Would that meet people’s needs at breakfast time? Because I’m also thinking, that not only for the time it takes Susan to set up but the time it takes all of you to clean up. [mild laughter]. Do people think that you could manage with that?

Kevin: Absolutely.

VTC: Everybody ok with that? Ok. And if anyone has difficulties let Susan know and she’ll put out the special thing that you need—that you NEED, not that you want. It is a good opportunity to see, what does my body need, and what is my preference for how I’m going to get the most pleasure out of samsara? Ok? So, learn to differentiate between: a dietary need, which some of us have, and just what we feel like eating and our preferences. Is that ok?

Susan: Sure.

VTC: And I really want to thank you for the wonderful job that you’re doing Susan. I want to say that the last three month retreat that I did, I had a lot of difficulty with the food for a variety of reasons. But, one of them was that the food didn’t have “umff” to it. And I realized that the food wasn’t being cooked with love. You know? And what I feel very much in what you’re serving is the love and kindness behind it. And that gives, when you’re meditating it makes a big difference. The people who take care of you, especially with your food make a BIG difference and if the food is prepared with kindness…

Discussion of a letter from a prison inmate: Attachment and the disadvantages of attachment.

Ok, the next thing is Bo’s letter.

[Note: The following discussion refers to a letter written by an inmate, named Bo. In the letter, he told Venerable the list of activities that he referred to as “nonnegotiable,” activities he is yearning to do upon his release from prison next year, such as skiing, having a home of his own, dating, surfing and riding his motorcycle. He indicated he could not consider becoming a monastic because of these “nonnegotiables”. Venerable asked all of us to read the letter and think about it and how it applied to our own lives… ]

Now, I have to say that I have not asked him personally if I could show this specific letter to everybody. I do have a general OK from him to share what he writes with others, ok. So you [turning to Miles] mentioned that you have written him a reply; before you send it, I should let him know that I showed his letter to everybody, OK?

There were other parts of the letter that were more personal that I didn’t share with you. Ok? I shared this part of the letter because I thought it would be something very helpful for you on retreat. That it would be something for you to think about and to use for a kind of mirror for yourself. What I would like to do is for each person to comment what your reactions were. But I want you to really think now what your reactions were so that when it is your turn, you say exactly what you think without it being influenced by what people before you said. Because people may have very different opinions and there is often a tendency, if I don’t want to disagree to say something other than what I am really thinking. So I would really like people to say what your ideas were about what he wrote and what it meant to you and if you face any of those similar things in your practice and so on and so forth. But, you don’t have to tailor it to fit what other people in the group say.

Kathleen: I want to go skiing with him when he gets out! [much laughter]. He really sounds like he goes to good places [continued laughter]. Really, I spent a lot of time in my meditation yesterday and today on this, because of what came up for me from the letter. First of all, I have my samsaric list also, but I wasn’t so clear about it until he just wrote, “This is not negotiable! 1, 2, 3, 4, 5!” And I thought, “Hmm, what do I have that’s like that?” You know, my son, being a grandma, writing fiction, are all things that I want and they feel not negotiable to me. So, I started looking at all that. And when we read the Three Principal Aspects after lunch each day, the phrase, “The pleasures of samsaric existence”, what’s the phrase… ?

VTC: Yeah, does somebody want to get a copy of it?

Nerea: “Without the determination to be free from the ocean of cyclic existence there is no way for you to pacify its pleasurable effects; thus from the outset seek to generate the determination to be free.”

Kathleen: yeah, that phrase just jumped out at me! Because of everything he listed and everything I had listed myself; I mean—there they are (the pleasures of cyclic existence). So then I started thinking about the “determination to be free” and what does it mean, you know? If you go skiing a lot, if I get my short stories published and then I die? [laughter] It just made me look at all that. At why those are not negotiable and what does that mean? So then, I thought of writing you two different letters. One is a “Bo” letter, saying, “These are not negotiable: and put being with my grand child, etc.” and then writing this other letter that says, “Ok, I’m giving them all up and am going to be a nun!” [much laughter]. And in my mind—it was very good meditation. Just doing that one and seeing what happened and then doing the other one and seeing what happened. You know there is no answer, it just brought all that out.

And there was one other thing that was a very good insight for me when I was working on attachment with my son and I had this different thought: I say I really love him—what does that mean? Am I just wanting him to be a certain way or do I want his enlightenment? And if I want his enlightenment, how do I need to be? And that was a new thought for me around this attachment. If I really love him, why wouldn’t I want his enlightenment? And if I want his enlightenment—what does that mean? And that was so scary!

VTC: Scary…?

Kathleen: I got so scared… I don’t know, it just brought a fear that I’m still exploring. You know, what does that mean, for what I need to do? So I’m still exploring, just this fear came. I really don’t know too much about it, but it was like “whoooosh” like that.

VTC: Good! Keep on exploring.

Kathleen: Ayeeeeeh! [laughter]. I want to go home. [laughter]. No… it has been very helpful.

Kevin: Well, it was quite a fascinating process. I took a long walk yesterday, right after you put the letter out and just spent the whole time with it. It was very rich. I have my list of non-negotiables, but what I realized in the way he presented it is… I can’t go back to where he is.

VTC: To where?

Kevin: It is like, all of the things that are my non-negotiables are crumbling. In that, I mean I love the beach, but, it is changing. I can still enjoy that, but it is less nonnegotiable. I guess it is an evolution that says I’m hooked (on the Dharma). Even though I struggle with my non-negotiables—my attachments—it’s kind of like there are a lot of freedoms in giving up the things that were non-negotiable in my life. Initially, especially those things that remain non-negotiable. I find myself with the clinging, the Eight Worldly Concerns with everything that he said—I thought about my house, I thought about my relationship, I thought about my kids—all the things that just seem so solid, and then I think about the places where I’ve let go of some of those things, and am keenly aware of other places where I’ve not (let go). What I meant earlier is that I can’t go back there, I’ve followed along too closely … to you. [much laughter]. It’s like the Twilight Zone, where you slip over to another dimension—Whoops, I can’t go back. It doesn’t mean the same thing anymore to me. I can still go the beach and enjoy that, appreciate that but it’s not a big deal. I don’t mean that I don’t have those attachments—I still love that—but it’s different.

VTC: It’s negotiable now.

Kevin: It’s negotiable now, and being able to watch that and distinguish between what is and what isn’t negotiable gave me a picture of the places and things that I have to work on. My goal really is to have them all be negotiable—I’m committed to that. So, what do I need to do for those other things to be negotiable? And how to be able to do that as Kathleen just said in terms of relationship stuff—how to integrate that and along with that, being able to let go. And like she was talking about, the enlightenment of her son… being able to act in a skillful way that’s best for everybody that I am attached to.

VTC: So how can I do something that benefits the people I’m attached to instead of my attachments setting the rules about what they should be—good.

Flora: I am in the middle of a mandala of things Bo wants… the ocean, the mountains, the lands Bo wants to see. It’s a balance between his freedom and his confinement. And he is projecting all this positivity onto the things he doesn’t have now. For me, I am in a struggle to integrate the Dharma into my life, into what I do, who I am. In this negotiation, my life is sometimes contrary to the Dharma. It’s not just eliminating what I am attached to; it’s transforming myself to where I am not attached anymore. I identify with Bo when he keeps explaining why he can’t be a monk; as though someone is asking him to do that. And I identify with that because my mind also is struggling with this as though there is someone or something pressuring me to do that.

VTC: There is no one on the outside (of your mind) asking him or you to ordain… is there? [laughter]

Flora: For him to be able to take that first step towards a better quality of life, to recognize not harming people is remarkable. Fifteen years ago I would have felt the same about his non-negotiable list. I would want to go mountain climbing, have a business, do martial arts, this and that, and now 15 years later, I’m still here. I don’t know how many times he will go after the things that aren’t really freedom; things out there.

VTC: Out there… I don’t understand. Nerea, can you translate what do you mean?

Flora: For him, he sees that list (of things he wants to do) as freedom and fifteen years ago I would have said the same thing and I would keep looking for it, out there. Now, I can see that it’s not really out there.

VTC: OK, so you’re realizing that the freedom and happiness isn’t so much with those things.

Flora: You can see the troubles that come up with money, partners… that’s all.

Aida: I wrote some things, so I will have Nerea translate. Basically, I’m not entirely agreeing with Bo, but through observing my mind and being honest with myself; I do think that I have my own list. In my mind it seems kind of obvious that happiness is out there, and that I look forward to getting it. Happiness lies in the objects, persons, animals and situations. And that happiness either was or will be, but hardly ever is now. For the past few days I haven’t been able to see Vajrasattva nor the light entering my body. The only thing that my mind can process is attachment of all sorts that are going to be what I have, when I get back to Mexico. It is like my mind denies that I can be happy and be complete right now—in every instant in my life, even if I’m separated from the things, people, animals and situations I enjoy. So then I asked myself, “Why is it that my mind doesn’t want to concentrate on Vajrasattva and the light? Why does my mind want things that it doesn’t have now and why doesn’t it appreciate what it has now?” So, to a certain aspect my mind goes along with Bo’s, but the only thing is that I don’t defend them consciously even though unconsciously they’re there.

VTC: Susan, did you want to join in on this?

Susan: I did read the letter. One of the things that I was struck by, and I only did basically read it, is that I appreciated that I felt I was reading something from people I know. I suppose for myself, I know that the thing I’m most attached to is myself, and, I’m not sure if that is negotiable or not.

Miles: Pretty much what came up for me was, that I felt your guys’ meeting [VTC and Bo’s met recently at the prison] must have been very powerful for him to express what he expressed so vividly. In the previous letter that he wrote he was talking about feeling like a walking, talking dichotomy and in my letter back, I said that Venerable has a way of doing that. [laughter]. And what I wanted to share with him in this next letter was how much impact he has had with just his words; on me, my friends and their families’—and people that I don’t even know [they have been corresponding since before retreat]. And I asked him if he could add something to his list of attachments. I suggested that he use his gift when he gets out to be a counselor for teenagers or something, to help show kids that they don’t need to do what he did. This thought has made me want to aspire to develop bodhichitta more by seeing that helping others has so much more impact and lasts, rather then any of the other attachments. It is really obvious when you compare the two.

Lupita: When I first read the letter I didn’t like it. I was expecting to hear something different but the only thing that I was hearing was the same thing that was coming from me and all the people I’m around. [laughter]. I don’t know much about his life, but what would I say to him? I went to the two extremes: very samsaric life, or monastic life. I’m living these two extremes in my practice now—he’s like me. I can see that there is a middle way. What would I say to him? Welcome to samsara’s prison. You’re just leaving one prison to enter another. The cell you were in before, that you could physically see and that you are determined to leave, but in this life (outside of prison) you have a harder life because you cannot see the bars. This might help you feel free. But you have to realize you’re still in a prison. And I hope you establish the wish to be truly free. You have the fortune to meet the Dharma. And my friend, this is the key—the master key to open all the doors. So remember it doesn’t matter where you may be physically. You have the key to either make yourself into a prisoner or to be free. That’s what I think to myself. So hopefully, some day in the future we’ll realize that we both have the key in our pocket.

Nerea: My initial reaction was, oh that’s my mind; wanting this, or wanting that, or grasping on, those thoughts about things that I couldn’t live without. Almost the same list: the music, the skiing, the this, the that, that I absolutely loved. And now that I have kind of had to give some of that up (to live at the Abbey)—music was the biggest one to give up, and it’s ok now and I am finding out why. So going from that extreme of knowing that that is how I used to be and now knowing how I am, with that and seeing what the change was and how imprisoned I was when I went to that. Now I am making up a new list of attachments and asking how can I do the same thing with those? And how do they actually affect me—just always looking for happiness out there [points around]. Just the point that he said, “I don’t want to get rid of my attachments!” He just said it like that and that is a lot of what I’m looking at. It’s like, I don’t want to get rid of them. And a lot of them aren’t material attachments, but mental attachments—ideas. Do I want to get rid of this concept? Do I want to get away from this idea, and a lot of the time I’m like, “No.” I like it because it is comforting, even though it’s self destructive, it’s comforting because it is familiar. I am just working with seeing all that.

Nanc: Well, I had two responses. I mean almost instantaneously, the first one was, “Bo, you’re heading for a fall.” And the next one was, “And I absolutely understand where you’re coming from.” You know, the mind, I could taste in his letter the sense of deprivation, the lacking, not having. The crappy, filthy, noisy prison that he talked about that he is going to be leaving and how he is going to be creating this pure land for himself; out of his senses being so neglected. And knowing, and understanding that I have my own list of attachments even though most of my worldly belongings have been given away. My attachments have been demons in the past week and a half on my cushion—how addicted I am. They’re more just the qualitative sort of attachments of reputation, and being right, being admired, being respected, things like that. And also, I could feel that he is just salivating right now—just chomping at the bit. I have many concerns for him. And one of them is that his incredibly non-negotiable, high expectations. This man has been incarcerated, he hasn’t been out in the world. He’s over fifty years old. Where’s he going to get the money? I mean I went into the practical aspect of it. You know, is this possible for Bo to get his happiness here? He’s got a lot of things working against him. And the other concern is that his repeated goal, “above all else, I want to be a good person and I want to do the right thing!” And in the search for the happiness of this life how much that goal gets tested; how hard it is to sustain your ethics when you are going after the happiness of this life—they just don’t live in the heart at the same time.

So, my feeling about the whole letter—and also it was colored through my relationship to Michael Powell [another inmate who she wrote to]. You know the, wanting to do it right and be so good. And once they get out of prison and into samsaric life, it is like throwing them to the lions. So, I have a lot of concern for Bo and that I have a lot of compassion for the both of us. Because I’ve been working on my list, but I absolutely understand and I was very, very delighted to see how he’s clear about what his attachments are. He wasn’t pussyfooting around. I guess he has had a lot of time to think about it. But, yeah, I’m worried for him; wanting to be this business man, wanting to support the Abbey. But what happens, I mean if none of this happens—if none of it transpires, would he be ok? If he doesn’t get the happiness of this life what will happen to Bo? Will he be able to cope? Will he have the support, the strength inside to say, “All right, no surfing today. I can’t afford the house, my girlfriend left me.” You know, is he going to be ok? Or is he, going to fall down?

VTC: hmm. Want me to tell you how I felt? [laughter]. It is very interesting listening to your comments, I really appreciate it. I don’t know if I should say how I felt or not? Umm, my first reaction was, Bo, you’re going to crash; that this samsaric pleasure doesn’t cut it, and setting that as your vision and goal of happiness is like setting oneself up for disappointment—setting oneself up for unhappiness. So, I wrote down some of the things I thought. I said, “It’s sad, because your life is intoxicated with seeking pleasure outside of yourself and I’ve never met anybody who could fulfill all their attachments to get all that they want. It’s natural after being locked up for so many years that you want to do all the things that you have longed for and dreamt of doing but you are living in your head. And then, I am glad that you say being a good human being is your chief priority, that’s the most important thing. But I am wondering, as you pursue your attachments, will the people and situations you encounter be conducive with this priority? Or will they spark the seeds of greed and anger that could make you go against your number one priority, which is to be a good person. The five precepts would be a very good protection.

It’s that same thing, you go out on your motorcycle and then your buddies want to stop and have a beer. Then you have a beer, then what do you do? Then they want to have a smoke and they want to have some drugs. You go skiing and then you know… When you’re seeking sense pleasures you’re coming in contact with people who have that as the purpose of their life too. You can often wind up going against your deepest held wishes; to do what’s right and to be a good person is very difficult, just because of the pull of the people you’re with when you’re seeking all that stuff. I also felt sad because there’s so much beauty inside of you that you and others won’t be able to see, because you’ll be busy 24/7 chasing after pleasure.”

After I thought about this for awhile, I was really glad that he was so straight forward and honest because most people aren’t about the things that are non-negotiable—they dress it up in other language like, “Oh, I’m going skiing this weekend with the family because it’s very good for the family and it creates a good opportunity for us all to be together”—leaving out the fact that nobody else except you in the family likes skiing. We usually present our attachments as if we’re doing something for the benefit of others. We’re not as frank and square as he is: “this is what I’m attached to and this is what I want”. It profoundly affected me—I found myself reacting to the intensity of the attachments and the fact that he said they were non-negotiable. First of all it was setting himself up for a crash and second of all this incredible human being, who I’ve come to see through the course of our correspondence, was nowhere present in that list of nonnegotiable things. He had written me this beautiful letter during the Iraq war where he had been watching Spanish news (which he said was more real than American news) and one time he saw this little Iraqi girl who was missing limbs and was completely a mess and his heart just went out to her. A few days later he was watching the news and they were showing some shots of a hospital and he saw her again. They had given her an artificial limb and he started to cry. I was so touched by this story of this human being caring for a little girl who was a total stranger.

Other things that he’s said and shared with me in his letters and the letters he has written to some of you—somebody I think could do so much good in the world like working with youth at risk, or in an old folks homes or working with kids with cerebral palsy; there’s some compassionate being in there. I was so sad and hurt inside, that that person was nowhere to seen in his list of non-negotiables. Attachment completely blows that wonderful person we are to the winds—attachment doesn’t let our compassion come out because we’re too busy looking out for me, me, me, me and what gives me pleasure. Another reaction I had was “wondering if you’ll be disappointed because your body is older and you won’t be able to do all those things.” I wrote some of these and some other stuff in a letter that I haven’t sent to him yet. But another thing that I was thinking but I wasn’t going to say but I’ll tell you. I was glad that I was able to meet him that one time—because if after he gets out all he wants to do is pursue his list of non-negotiables, I’m never going to see him again; he’s going to be too busy with all that. Then I was sad because “all you want to pursue is all about what will make you feel good and that self-centered attitude won’t bring you or others happiness and sad like watching the sun of your kind heart sink in the ocean of attachment.”

Those were my initial reactions, when I wrote to him. Afterwards I had some other thoughts and I realized what some of you had said, that he is putting it out as two extremes and it doesn’t need to be two extremes. The situation he’s facing is what we’re all facing—which is how to chip away at our attachments in a way that we can actually do. Like picking out the things that are most important and really chipping away at those. I realized as I was writing, that, one’s goal has to be “I want to get rid of my attachments!” And if your goal isn’t, “I want to get rid of my attachments”, then Dharma might help you be a little more peaceful or help you with your anger—but there’s no space for liberation if we don’t want to work at ending our attachments. And so, I wrote that our aspiration, if we are really interested in the Dharma is to let go of all these attachments, because the attachment is bondage. Not because it is bad—it is bondage. And so, that is our aspiration and we go there slowly, slowly—each at his or her own rate, dealing with things in a way that’s comfortable.

And this situation of being a walking, breathing dichotomy—for everyone who has a Dharma aspiration—this is what their life is like. If you have no Dharma aspiration, you are not a dichotomy. You want to pleasure of this life and you go for it. But when you think of beginningless rebirths; that we have been doing that since beginningless time. Where are the Three Principle Aspects [by Lama Tsong Khapa] again—because some of those lines came to my mind: [VTC reads from the text]: “For you embodied beings bound by the craving for existence, without the pure determination to be free from the ocean of existence, there is no way for you to pacify the attractions to its pleasurable effects, thus from the outset, seek to generate the determination to be free”. That’s really having the destruction of your attachments as something that you want to do; because you realize that will bring happiness and make your life meaningful. The other thing that really hit me [she reads again]: “Swept by the current of the four powerful rivers; tied by the strong bonds of Karma, which are so hard to undo; caught in the iron net of self-grasping egoism; completely enveloped by the darkness of ignorance; born and reborn in boundless cyclic existence, unceasingly tormented by the three sufferings; by thinking of all mother sentient beings in the condition, generate the supreme altruistic intention”.

And so then, I read his letter in the evening and the next morning, when I was doing my daily practices, which I often do like we all end up doing—probably like you when you do Vajrasattva a lot—you know—“Oh yeah, I take refuge in… Buddha, Dharma and Sangha—oh yeah, I generate the altruistic intention—oh, there’s Vajrasattva and VajraDhatu, oh yeah, I’m glad they’re still here—yeah there they are in their celestial silks—hmmm—I wonder what we’re having for lunch today—Oh yeah, there’s the OM at their heads—oooh—it will be so nice to get outdoors—oh yeah, the AH at their throats—I really want to go to the shopping center and oh yeah, a HUM at their hearts—and I wonder what movie I will go see—you know how meditation often is… OK? [lots of laughter of recognition].

Well, the morning after I read Bo’s letter, my prayers and practices had a whole new meaning for me. And I was visualizing the merit field and saying to myself—Yeah, these are the people I want to be around. I want to hang around the lineage lamas and the Buddhas, Boddhisattvas, Dakas and Dakinis. I don’t want to hang around—for me it was dancing… and other stuff… I don’t want to hang around the people I did those things with. The people I want in my life are the Buddhas and Boddhisattvas. So it made my practices different; very affirming—this is what I want—I have done all that other stuff. That’s another thing that hit me; all those things Bo is dreaming about doing—he has done them before and where did they get him? For all the pleasure they gave him; he’s been sitting in prison for almost 16 years. So how does that stuff bring him happiness? He’s done it all before.

And I was like, “Yes, Buddhas and Boddhisattvas—come here, I want to hang around you. I don’t want ski buddies. I don’t want my beach friends, my dancing friends”. It’s not like I am pushing them away but more like setting what my priorities are. Because, it’s like, those old friends… well, in my case, I’ve been in the Dharma 30 years now, so a lot of it has changed just by time passing, but it comes around to what we we’re saying at the beginning of this session about cherishing our Dharma friends and the people that you do practice with. They understand and support that side of you. When your own mind and the people you are around are only seeking pleasure, pleasure, pleasure from external objects… that kind of mutual love and respect isn’t to be seen in those kind of relationships. Do people have other comments?

Aida: This comment is not very clear… but I will try to say it. I think I am realizing that Bo is making a strong difference between two parts: on one side, he wants to be a good person, but this is disconnected from getting rid of his attachments. It’s like there were two completely different things; unrelated, so you can choose this and that. But the thing I want to say is that this is the common way we see things, disconnected. It’s the easy way to see things. He’s not realizing that everything is inter-connected. So, as you were telling us, if you ride your motorcycle, what’s the next step? To get a beer and then on and on and this is not very conducive to being a good person. So it’s interesting to notice that.

Susan: I just want to share, it was very interesting what I shared tonight with you. And I appreciate that you started by saying for everybody to hold their own piece. I, obviously, did not. I shouldn’t say “obviously”. I did not. And that’s very interesting and what was very good for me personally was that the people before me did talk about the non-negotiables and that was very interesting; because I obviously did get in touch with that piece of myself.

VTC: Right, and I think that’s an important thing and that is one of the reasons I shared the letter. So that we could all ask ourselves, what are my “non-negotiables”? And, do I want to make them negotiable? Or am I going to keep them as non-negotiable?

Kathleen: There’s something kind of haunting in the phrase, “the determination to be free”—that kept coming up when I was reading his letter. How do I say this? If the determination to be free gets strong enough, I think people do become monastics. Because, even living a good Buddhist lay persons life, there’s not time to really go in depth and to understand. I was reading the Introduction to Tantra by Lama Yeshe and he’s talking about tummo and all that and I’m thinking, Oh, I want to know that, and then thinking it would take so much time to even begin. And when I get home, if I can do my hour and a half a day… I mean, I fight to do that… I do it, but I have to push and negotiate and shut the phones off and say, “No, I won’t!” Just to do an hour and a half, my one little practice. So, it seems to me that monasticism is intrinsically tied with this determination to be free. Is it?

VTC: I think it is. I think it is. It doesn’t mean that if you are not monastic, you don’t have any determination to be free; because the determination to be free is something… it’s that light switch that you turn on. It’s like refuge, you know, it’s the turning light switch. Refuge isn’t on or off. You take refuge and you start small and you increase it and increase it and the light gets brighter and brighter and it’s the same with bodhichitta. It’s the same with wisdom; it’s the same with the determination to be free. All of the realizations on the path aren’t on and off. You start small and you slowly develop them. But my way of looking at it is, that I think the monastic lifestyle is indicative of a stronger determination to be free because you want the time to devote to the path. Also, when your priorities shift, you’re not so interested in doing the things you used to do. They don’t seem quite so interesting anymore and what’s more interesting is your Dharma practice. But I really want to stress that it is not an “on/off” light switch. Lay people can have very strong practices and some monastics can have very weak practices. It’s an individual thing.

But the lifestyle itself, I think, is much more conducive. It’s clear in the sense that… Ok, take something like sexual desire; Ok, everybody has sexual desire, right? I mean, we might as well admit it. Now, if you have a shaved head and wear the same clothes every day, people aren’t going to flirt with you as much. [laughter]. So, it just makes it easier for yourself not to get into that energy. We each portray ourselves to the external world in terms of how we want to be treated and if you have a shaved head and are wearing robes, that’s different than if you have tight fitting clothing and long hair and perfume and that whole thing. It just makes it easier; because you are sending a message to yourself, first of all. “OK, I am representing the Buddha’s teachings, I better behave myself.” But second, other people are seeing you in a certain way and it’s like, good, I want them to see me that way. I don’t want anybody flirting with me. So then it helps in that way to let go of the attachment. How are we doing time wise? It’s 8:25pm. Are there other comments on this?

Nanc: The other thing is when you asked how does what Bo said relate to your life and your practice… are there any similarities? This practice is all about purifying those negative actions we committed in order to attain the happiness of this life. So for all the good times we had, we are now taking care of all the ways we may have, or I should say I have achieved or acquired those things. It doesn’t feed a positive cycle. It feeds a negative cycle.

VTC: Right. One thing that is very important—we shouldn’t say to ourselves, “Attachment is bad—I’m not supposed to be attached.” Or, “If I’m a good Buddhist, I’m not attached. So, I’m attached, therefore I’m not a good Buddhist.” Those are complete wrong conceptions. OK? You can look everywhere in the scriptures; there is no place where the Buddha said you shouldn’t be attached. There’s no place where the Buddha said you are bad if you have attachment. And there’s nowhere where there is a printed catechism that you have to put your thumbprint on in order to call yourself a Buddhist. OK? There’s none of that. We need to be very, very clear in our own minds about this.

The reason we try to diminish attachment is because we are able to see, when we examine our own experience, that attachment leads to suffering and we want to be happy. Because, we are able to look at our own experience and see when attachment is manifest in my mind, right now at that very moment, my mind is not happy. And when attachment is manifest in my mind, to get the things I am attached to, I do the ten negative actions. So then, when I die, all the things I was attached to stay here and what comes with me is all the negative karma that I created in getting them. Because you lie to get what you want. You clock in for time you didn’t work; so you are stealing. You cheat on your taxes. You sleep around with other people. You say harsh words against people who criticize your reputation. You talk bad behind peoples’ backs because you are jealous of them. And we do all these things in order to get the eight worldly concerns; to get our material possessions and money; to get our sweet words of appreciation and love, to get our reputation and good image; to get all the pleasant sense objects that we want, then we create all this negative karma and wind up having suffering in the future because of it.

So, understanding that, from our own experience, the karma we create—and how deceptive going for pleasure is—because it’s so temporary—but the karma continues on. That’s one thing. The second thing I’m really seeing that right now, when attachment is in my mind, my mind is not happy; not free. And this is what is so deceptive about attachment because it creates a bubbly, excited feeling; “Oh I’m going to the beach!” You know, I grew up in Southern California, tell me about the beach. But then, you look at your mind, is it happy when the attachment is there? No, it’s not, because we have a feeling that in this present moment we are missing something—the happiness is either in the past, or the future. So we are grasping at something that isn’t here. So then, there’s frustration because we can’t have what we want, you know, or because we had it and due to its’ impermanent and transient nature we no longer had it; or we got it and it brought problems. Yeah? Like sitting in the traffic jam on the way to the beach, or going skiing and—do you know how many people have died skiing?

So if we look right now, we see that there’s no real peace and joy in the mind; and then how it obscures this whole compassionate, kind, really loving side of us because the attachment is basically self-concerned. So, I think the determination to be free comes through looking at our own experience; not through saying, Buddha said, blah, blah, blah and therefore I have to make myself feel bad. No. Buddha always emphasized; look at your own experience. He just described what his experience was and gave us complete free choice. Look at your own experience. What’s happening in your life? What’s happening in your mind? It’s like in the precepts ceremony that I wrote, “Through my own examination and experience, I see that the taking of lives… this is what it leads to… or I see that unwise sexual behavior… this is what it leads to…” And so, it’s really emphasizing our own experience and making our own wisdom arise. Because you can’t practice a spiritual path if you feel that you are doing it because you should. Buddha said you should or you’re going to Hell if you don’t. You know, we often—and Kathleen it might be nice if you talk about this, because it relates to the note you wrote me—which I brought.

Religious conditioning

Kathleen: Oh, I talked about hell in the motivation yesterday… about hell and bliss.

VTC: What I really got out of your note was that sometimes we grow up with certain religious conditioning when we were kids and we don’t even realize that we’ve had that conditioning. Then we come to Buddhism with those same preconceptions and project them on the dharma. Like, “I have to believe certain things in order to be a good Buddhist.” Well, Buddha never said that. Or, “I shouldn’t be attached.” Well, Buddha didn’t say that either. Or, “I’m going to hell if I have doubts about something.” Well, Buddha is not sending you to hell. We import some of these preconceptions that we don’t even realize we have and then we start to fight with the Dharma. And I think that’s what causes that extreme mind that you were talking about—of either you’re a monastic or you’re completely in the middle of samsara. It’s that way of thinking that creates that extreme mind. Whereas our lives are not like that; it’s not this or that. Did you want to talk a bit about this? Or do you want to read the note you wrote me?

Kathleen: Sure, would it be helpful?

VTC: I think so.

Kathleen: I wrote a note to Venerable because I was having a lot of thoughts one day. So, I wrote: “I want to share with you two recent insights from the practice. They have made me very happy. First, about wrong views—I’ve often glossed over this negative action in my meditations, thinking I am a progressive person who has thoughtful and kind views. Thanks to Vajrasattva, I came upon a disturbing set of views that I was born into—a conservative Catholic family culture and religion, where nearly everyone believed, taught and enforced three ideas: First, we are all born bad, with Original Sin. Second, we cannot get rid of it ourselves. We have to rely on an outside source, God, Jesus or the priest in confession. And three, if we aren’t saved by them, we lose our very soul, eternally in hell and no one can get us out”. Venerable, what I didn’t write to you, but did share in motivation this morning is that a nun in a religion class, when we were only seven years old, told us that our parents would not be able to get us out of hell. And, that was horrific. [Back to the letter]: “This set of beliefs is terrifying and I see how much suffering has come from it. I am still exploring that, it seems endless. So, I am sitting now with what I must have done in previous lives to reap this karma; spiritual abuse is a phrase that comes to mind—forcing wrong, damaging fundamental views on adults and children that keep them from knowing the truth of our basic, essentially pure nature. Of course, the church also gave me many good views too; the ethics of the ten commandments—Lupita and I talked about that—loving God and my neighbor as myself; Jesus life and the saints lives to emulate, but this basic core wrong view was there too and as a child, it seemed I had no way to resist it. This is a core issue for me and I am happy to purify it. It helps me to understand my family so much more. Thank You.” Should I read this next part?

VTC: Yes, I thought that was good too.

Kathleen: [Reading again]. “My second insight was about relying wholeheartedly on a spiritual master (step one in the Lam Rim). I have been working with this idea for a few days and have questions galore. Have I ever relied on anyone or anything in my whole life, whole-heartedly? I see I do most things _ or _ heartedly. So I am exploring what this means to me. This morning, I realized I can and do rely wholeheartedly on the Six Perfections, The Four Noble Truths and the Four Far Reaching Attitudes. It was a relief to find there are some ideas and qualities that I can do that with. I have also thought how successful I have been with various activities even functioning _ or _ heartedly, like: work, parenting, relationships and the Dharma. But I am now asking myself, what happens when someone does whole, with all their heart? And you came to mind. I think, due to your complete commitment to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, all three worlds serve you and the Abbey. And I am looking at what I am protecting or holding back when I am not whole-hearted; and of course, it is my ego. Well, I felt compelled to share these insights with you…”

VTC: Shall we leave your note downstairs in case people want to read it again? I thought it was very nice.

Nanc: I found, when Kathleen shared some of this in the motivation the other day, I had been ruminating about my aversion to some of the practice and finding out that a lot of the issues around confession; as a child going into a confessional [that box] and having that silhouette in there, and saying, “Bless me father, for I have sinned”. And the whole idea of being six years old and having sins that I had to confess to this person in the box and that only by his authority do I get forgiven; so, I somehow brought that into the Vajrasattva practice and anything with prostrations and purifications and negativities bring up this confessional. And I have had this struggle with putting this priestly absolution thing onto Vajrasattva and it’s really gotten me into a little bit of a stuck place right now, with that whole determination to realize that that is happening and that it can happen. So, I could hear Kathleen; it was coming into my heart during the motivation.

VTC: I think all of you were raised Catholic except Miles? Miles, you were raised what?

Miles: Christian.

VTC: Yes. General Protestant. But all the rest Catholic yes?

Kathleen: Yes, everyone. I asked when I gave that motivation because I started thinking… I knew Nancy was and then I thought most likely if people come from Mexico…

Flora: Well, my mother used to be Jewish, but after they married, she became Catholic.

VTC: Yes, and so it is very easy to do what you are saying, and Vajrasattva becomes the priest. But, just as the priest was a projection of your mind, Vajrasattva is a projection of your mind; and look at what you are projecting. It is not there from the side of the object.

Kathleen: I also struggle a lot with the hell realms. Every time I read about the hell realms and I noticed in the Vajrasattva retreat every time I come across them I just go, “Oh I’m skipping those.” [laughter]. No, really—I just noticed it. I go, “Oh, he is going to list all the blah, blah blah. [gesture of flipping pages] where’s the real stuff?” I don’t want to hear it. I go, “Oh, I’m not sure that is real I’m going to skip all that.” It is really interesting to watch my mind.

VTC: I think this is the benefit when you start practicing Dharma, you start observing that. You know? Where’s that coming from? In this case you can see clearly the conditioning you had before and where it is coming from. But, “Well, what does it really mean to me? What do the hell realms really mean to me now?”

Lupita: I remember on one occasion a friend told me, “I make the determination that I don’t bring with me the faults of the other person (original sin)—the action the other person did.” I have a lot of thoughts in this moment, and she said, “Don’t bring the concept of Eve’s fault to me.” Because Eve (Adam and Eve) took the apple and ate it, I didn’t take the apple. Eve took the apple, it is her fault”. [laughter]. Don’t bring that with us to Buddhism, this “fault”.

VTC: Let Eve eat the apples and I’ll eat pears. [laughter].

Flora: I have the experience of Kathleen as seeing it as an obstacle to the practice, but I have another way of being able to see Vajrasattva and being able to connect with the Buddhas; going back to my childhood and invoking the same feeling I had for Christ or Jesus. Being able to see it as a pure being and being able to see the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas through that light. Up until the last couple of days, I’ve been doing a lot of my recitations in the Catholic mode. In the last couple of days I’ve been praying to God to help me see Buddha. [laughter]. “Please, God, I need to understand…”.

VTC: [laughter]—This is good that we see all this.

Flora: My first spiritual experience was Catholic. If I’m thinking about devotion—love for pure beings, my first emotion is toward the pure beings that I knew first. My experience with the Catholic world was nice. It was not enough, but it was not—I don’t think of it as bad.

VTC: You can build on it. So, you all can go in there after this and say, “God, please help me.” [laughter].

Kathleen: Yes, the Catholic nuns used to give us holy cards if we did good work and so Kevin and I have been exchanging these—he gave me a picture of Vajrasattva, like a holy card [laughter] …we really are mixing our pasts in.

VTC: Susan, were you raised Catholic too?

Susan: Yes, it’s all of us.

Flora: But my mother was Jewish and didn’t like the Catholic part so much.

VTC: Yes, I understand. I grew up Jewish and wondered about Christians. And growing up Jewish, you have a whole other set of baggage… [laughter]. Seriously, the reason my family is in America—all four of my grandparents came from different parts of Eastern Europe, Russia, Poland, Belarus and the Ukraine they all came from there to America, because they were getting persecuted. So, to flee, they got on boats and then off the boats in New York and—new language, new everything… they didn’t know anything and they made a life here. That’s why I’m here. The other choice for them was to stay in the old country and get gassed, which is what happened in the areas where all my ancestors lived, Jews were all rounded up and sent to the concentration camps and killed. [Some discussion ensued about Jewish holidays and ways of overcoming their past oppression.]

VTC: So, I think we did enough for this week… Let’s dedicate the merit from this discussion.

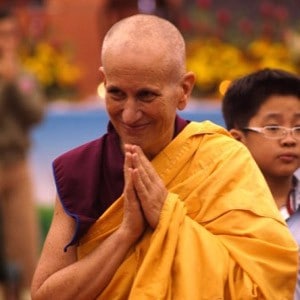

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.