General characteristics of karma

Verse 4 (continued)

Part of a series of talks on Lama Tsongkhapa’s Three Principal Aspects of the Path given in various locations around the United States from 2002-2007. This talk was given in Missouri.

- Karma and the faults of cyclic existence

- Four aspects of karma

- How karma results correspond to their causes

Verse 4: General characteristics of karma (download)

To generate the determination to be free, we eliminate clinging to any kind of happiness in cyclic existence.

In talking about the three principal aspects of the path, we were talking about renunciation or the determination to be free. That has two aspects to it. First is eliminating the clinging to this life, and then eliminating the clinging to future lives—to any kind of happiness in cyclic existence. We finished talking about how to eliminate the clinging to this life. Remember clinging to this life is attachment to the happiness of only this life—as exemplified by the eight worldly concerns and all of their marvelous manifestations that we practice so diligently and with great conscientiousness and perfection. The methods to do this, as Je Rinpoche says in The Three Principal Aspects of the Path, are first remembering the freedoms and fortunes (or leisure and endowments) of our precious human life. Then second is remembering the fact that we’re going to die—our mortality.

The meditation on death that we’ve talked about a couple of times is a very important one. It makes a huge difference if we remember death every day. It makes our life really vital. We really appreciate our life. We really live it. We don’t coast along and live on automatic. We also get more of a sense of purpose in our life.

We’re going to move on now to the second sentence in the fourth verse:

By repeatedly contemplating the infallible effects of karma and the miseries of cyclic existence reverse the clinging to future lives.

The two ways to generate renunciation for all of cyclic existence (including happy rebirths) is by remembering karma and by remembering the faults of cyclic existence. I thought to talk about karma today. There’s a lot of interesting stuff in the topic about karma. I don’t want to make it too detailed. We could spend three, four, five sessions on karma. As I was preparing for this class I decided that it’s better if we have a special course sometime just about karma. This time we’ll hit on some highlights of the topic. But you know me, how I get distracted and never finish stuff on time. We’ll see how far we get.

Actually observing karma is the core of the whole path—the foundation of the whole path. It’s the first thing we have to do. Without doing this there’s no way to build and get higher realizations. This is incredibly important because the whole topic of karma is speaking about ethical discipline and really getting our life together. As you’ve probably heard me mention so often, some people come to the Dharma and want very high fantastic practices and experiences. But they don’t want to change their ordinary habits on a day to day basis that create harm for themselves and others. Whereas what the Buddha really advises us to do, the foundation of our practice is to get our daily life together. So the teachings on karma really go into that in great depth. I personally find them very interesting. This is because when you apply the teachings on karma to our own actions, then what we do on a day-to-day life basis takes on a whole new significance. It’s very interesting.

There are four general characteristics of karma that are helpful to understand. Before we get into them remember karma means action. It means actions that we do physically, mentally, or verbally. In particular it’s volitional actions. In other words, it’s actions done with some kind of intention. The word karma is also often used for actions that are done accidentally without any intention—some karma is created with those. But generally when we’re talking about karma, it’s the karma that brings full results. A full result refers to what we’re reborn as and the other three results. With these then we’re talking about volitional actions with a definite motivation.

Karma isn’t anything magical or mysterious. Karma is actions and those actions bring effects. It’s talking about cause and effect. Scientists talk about cause and effect in terms of physical properties. Buddhists talk about cause and effect in terms of actions and their results. So this is more on a mental level so to speak.

I should say karma also means, at least sometimes the way the word karma is used nowadays, it means, “I don’t know.” Like why did this happen? Well, it’s his karma. In other words, “I don’t know.” Often we use the word karma in a very flippant way. Like when we can’t explain something we just say, “It’s just their karma.” I think that’s really flippant. It’s not really considering the fact that anything that occurs had prior causes and conditioning—and to think about those causes and conditions that come together to cause a certain event. So not to use karma in a flippant way like, “I don’t know why that happened, it’s karma,” meaning like magic. I say this because once a word appears in Time magazine, then you know you have to start defining it more accurately.

Karma is definite

Karma is definite. In other words, happiness comes from positive actions, unhappiness comes from destructive actions. Now this first one I find very interesting because Buddha did not make up this law of karma. Buddha did not say these are positive actions and you’re going to get rewarded for doing them; and these are negative actions and you’re going to get punished for doing them. Buddha didn’t say it that way and he didn’t make up the cause and effect to be like this. Buddha only described it.

The way the Buddha did this is first he looked at the effects. Buddha had great insights and clairvoyant powers due to the elimination of defilements on his mindstream. He looked and whenever he saw sentient beings experiencing happiness, he was able to see what actions caused that happiness. Those karmic actions were called positive. They were labeled positive because the result was happiness. When he looked at sentient beings suffering and the actions that caused them, those actions were called negative or destructive. That’s the label given to them because they brought unhappiness.

This is important to remember. Something is not positive or negative, virtuous or non-virtuous inherently in and of itself because God, or Buddha, or somebody said so. Nothing is positive or negative by its own nature, independent of everything else in the universe. Something becomes labeled positive because it brings the result of happiness, and is labeled negative or destructive because it brings the result of suffering. This gives a totally different flavor to the talk of cause and result than you get in some theistic religions—where a supreme being invented the cause and effect and dishes out the rewards and punishments. In Buddhism there are no rewards and punishments—things just bring results. Again this is important to remember.

I’ve seen some Buddhist texts that have been translated by people who use Christian vocabulary. I remember reading a translation of the Medicine Buddha sutra and it talking about people getting punished for this and that. This totally gives the wrong meaning. It’s a translation done by somebody who used Christian vocabulary and who didn’t understand the Buddhist meaning. I say this because there are no rewards and punishments in Buddhism, there are just results. The results correspond to their causes. If you plant carnation seeds you get carnations, you don’t get roses. If you plant rose seeds you get roses, you don’t get carnations or chilies. Things correspond to their result but they aren’t rewards or punishments. So remember that we aren’t rewarded or punished, we just experience results.

I think psychologically that’s a very important thing to remember. It’s especially important to remember that the Buddha is not a supreme being dishing out rewards and punishments. Buddha just described the system. If the Buddha was a supreme being dishing out rewards and punishments, and controlling this whole thing, then we should definitely protest. Tell the Buddha to do a better a job because there is no reason for sentient beings to suffer. But that’s not what’s happening at all. We are creating our own future by the actions that we do now.

This teaching also comes back to why Buddhism is a practice (or religion if you want to call it that) which is one of personal responsibility. This is because we create the causes for what happens to us. This means that if we want happiness, the responsibility is ours to create the causes and the power is ours to create the causes. We don’t have to propitiate somebody external to us to rearrange the conditions in our life so that we’re okay. What we need to do is create the causes for them.

Karma is expandable

The second quality of karma is that it’s expandable—in other words, a small action can bring a big result. The analogy is often given of a small seed or a small cutting which can grow into a big tree that bears many fruits. Sometime you might look at the small thing, like when we planted trees a little while ago. Remember when we got 1,200 trees and they arrived UPS. They looked like twigs. That twig later on can become a huge tree with a lot of different fruits and things going on. Similarly in terms of our action, a small action has the potential to bring a big result. This is important to remember because it makes us more alert.

Let’s say that we’re tempted to do something—a harmful action. Sometimes ego mind says, “Well, it’s just a little harmful action. It’s just a little white lie. It’s not so important.” We make up these excuses to ourselves on why it’s okay to do this. But if we remember that a small action can bring a big result, and a big painful result in this case, then we’ll have more energy to abstain from that action.

Similarly in terms of positive actions, sometimes we’re a little bit lazy to create them. Especially we have the practice of getting up in the morning and making three prostrations, taking refuge, and generating our motivation when we get up in the morning. We might think, “Oh, that’s just a little positive action—doesn’t really matter. I don’t need to do it.” If we remember that small actions can bring big results then we’ll take the opportunity to integrate that positive kind of action, behavior, and mentality into our life—because we’ll see that it does have a profound effect on our life and lives.

If the cause hasn’t been created, the result won’t be experienced

The third quality of karma is that if the cause hasn’t been created, the result won’t be experienced. In other words things don’t happen accidentally without causes or randomly. If we haven’t created the cause for something to happen we won’t experience the result of that thing happening.

This can be used to explain many things that we see in our lives. I remember hearing one story that really made a profound imprint on me. In Seattle a number of years ago there was big fire in a warehouse. A number of firefighters went in and were killed in the fire while they were trying to put it out because the floor collapsed. There was one squad of firefighters or group of firefighters—about four of them. They were supposed to go in. They were on their way into that building that was burning before the floor collapsed. Then one of the firefighters, his suspenders broke. Now how often, if you’re a firefighter, how do your suspenders break? I mean come on! It’s not the average thing that happens. Because this one guy’s suspenders broke he couldn’t go in, and because he couldn’t go in that small group of firefighters couldn’t go in. These guys didn’t die in that fire. To me that was an incredible story. If you haven’t created the cause, you don’t get the result.

Now here the cause, if we look in terms of karma, this is an example of when people die an untimely death like these firefighters did. In other words you die before the extent of your life span has been lived out. It’s generally due to a very heavy negative karma created in previous times. It ripens as this heavy event that cuts off one’s life prematurely. But if one hasn’t created that cause, even if you are so close to a big accident that could kill you, you don’t wind up being killed in that accident. Do you get what I’m saying? It could be some kind of situation. Now here I’m randomly guessing—I have no ability to know. Maybe in a previous life all these guys were soldiers in an army together and we’re doing an assault. While some of the soldiers went in and were really savage attacking others, another small group of them decided, “Hey, we don’t really believe this. We’re not going to do this.” So they didn’t do that action. It could be because of that, then in this life there they are together but in a different configuration. The ones who did the savage attack are the ones whose karma ripens by their lives being cut off prematurely. The ones who decided not to and even risked court martial because of it? Then the suspenders broke and they didn’t go in the burning building. It’s hard for us to know. We don’t have the clairvoyant powers to know exactly who did what/when that brought about some specific result.

There are many stories in the scriptures where the Buddha was often asked about unusual things that happen. People said to the Buddha, “What did these people do in a previous life to cause this?” He would tell these different stories. If you read the Jataka tales, the story of the Buddha’s previous births before he became the bodhisattva and the Buddha, then you see lots of these kinds of stories. Stories of how people meet repeatedly in different lifetimes. According to how they related in one lifetime effects what they experience together in another lifetime.

It’s quite interesting. We hear stories of people, like on 9/11. People who normally go to work in the World Trade Center, and that day they didn’t go to work. Or people who usually don’t work in the World Trade Center but that day they had a conference or a symposium. So they went there. All that kind of stuff happens because of our previous actions. If the causes aren’t created, the results won’t be experienced. That was an example in terms of experiencing negative result.

In terms of experiencing positive one results it’s similar. If we don’t create the cause for happiness we’re not going to get happiness. If we don’t create the cause to gain realizations of the path, we’re not going to get them. If we don’t create the cause for liberation and enlightenment, they’re not going to come. This is really emphasizing again our own responsibility. It’s not up to the Buddha to practice for us or make us enlightened. We’re the ones who have to create the causes for that.

Remembering this—that if the cause isn’t created the result isn’t experienced—we meditate on this. Make a lot of examples in our lives. This really helps us to be very vigilant about the kinds of causes we create and the kinds of things that we engage in. This is because we know that if the cause isn’t created, the result won’t be experienced.

Karma doesn’t get lost

The fourth quality of karma is that it doesn’t get lost—it doesn’t vanish. Our computer files sometimes vanish without our knowing what happened to them, but our karma doesn’t vanish. Something that we do in one life can plant seeds in the continuity of our mind—our ever-changing mind. Those seeds may not ripen for many lives or eons, it’s hard to say. But those seeds don’t get lost. They don’t fade away with time like our laundry fades when we hang it out in the sun over time. It doesn’t happen like that.

Now that doesn’t mean that things are fated and predetermined and that there’s nothing we can do. It doesn’t mean that karma doesn’t get erased, like, “Okay I did a negative action. Well, then I’m doomed.” It doesn’t mean that because there’s a lot of flexibility within the system of karma. Karma is cause and effect, so it talks about conditionality. It doesn’t talk about predestination and rigid things.

In the case of negative actions if we counteract our negative actions by purification then we cut the energy of the negative action. In terms of our positive actions, if they get opposed by our getting angry or generating very strong wrong views that impinges on the ability of our positive actions to bring their results. There is this kind of flexibility. Things aren’t doomed or predetermined. Understanding this gives us some energy to do purification practice. I don’t know about you but just looking this life I’ve created a ton of negative karma. Now that’s not going to vanish over time. I have to do something that actually manages to cleanse that from my own mindstream. We do that by the four opponent powers which I‘ll speak about a little bit later.

In a similar way when we do create positive actions it’s important to protect it. This is because our positive actions aren’t concrete. They can be affected by other causes and conditions like anger or wrong views. So we want to protect them so that anger and wrong views don’t impinge upon them. We do that through dedicating the positive potential or the merit. Also through realizing that ourselves as the agent of the karma, the karma itself, the action itself—the object we did, and the result that we’re going to experience—all these things are empty of inherent existence. Dedicating with an understanding of emptiness helps us protect the seeds of our positive karma so they don’t get damaged.

Remembering this fourth one gives me more energy to do purification. I really review my life, and clean things up, and regret the things that need to be regretted. It also gives me more energy to pay attention to dedication at the end of positive actions. It gives me more motivation to try and avoid getting angry. This is because when I think of anger as a conditioning factor that interferes and dampens the effects of my constructive actions, then I don’t want it to do it. Then that gives more energy to avoid getting angry and hostile.

Those are the four general characteristics of karma. When we meditate on this or even discuss it with each other, it’s really helpful. It’s interesting to make examples from our own lives, and from what we hear about and read about. It can then really help us understand the teachings of karma. It can help us understand our lives and why things happen the way they happen.

Often when somebody gets sick one of things that comes up is, “Why me? Why do I have kidney disease? Why do I have cancer? Why me?” People ask that a lot and they feel like victims, “The universe isn’t treating me right. Why did this happen to me?” Well, if we have an understanding of karma then we understand that things happen due to causes and conditions. Some of the causes and conditions might be this lifetime in terms of diet and activities but we also have conditioning from prior times—whatever our actions were. So things aren’t without causes. We created the cause. It can be very helpful when we’re experiencing some suffering instead of saying, “Why me?” and rejecting the suffering. Instead of saying, “This is unfair. The universe should be different” to say, “I created these causes so I’m getting the result. If I don’t like this result then I have to be careful not to create the causes that bring it in the future.”

This way of thinking is a thought training practice. It can help us avoid getting angry when we experience suffering. We see there is no sense blaming anybody outside of ourselves because we were the ones who engaged in the negative actions. It also helps us really reflect on our actions and begin to change because we see that our actions bring results upon ourselves. If we don’t like these results then we need to clean our act up. I think that can be incredibly helpful.

I know for myself that way of thinking really helps. Say if I feel that I’m being treated unfairly. I usually start out doing that and complaining, but then eventually I realize how miserable I am. Instead of blaming other people I have to say, “Well, I created the cause for this, and since it’s an unhappy result, it was a harmful action I did. I did that action under the force of my own selfishness.” I say this because we don’t create negative actions when we’re acting for the benefit of others, we create them when there’s selfishness. “So I have nothing to blame basically but my own self-centeredness and my own ego-grasping—my own self-grasping. I’ve got to do something about those and I’ve got to refrain from harmful actions.”

This helps me a lot especially in things like somebody talks badly behind our back, and then we feel hurt and we feel angry. But if I look and I say, “Well, when I feel that it’s unfair that somebody talks behind my back,” but then when I look? Again, just forget about previous lives. Even this life, have I ever talked behind anybody else’s back? Well, yes lots of times, many times. If I’ve done that why am I so upset when somebody is talking behind my back? Why do I get so mad at that person for doing this and think it’s all unfair when I’ve done the very same thing many, many times. It’s kind of like, “Chodron, look at yourself and clean yourself up and stop blaming others.” So that technique, that way of thinking and understanding karma can be very helpful in our practice.

This thing of saying, “Why me?”—we very seldom do it when something good happens. We very seldom have happiness and say, “Why me?” We all had food to eat today, didn’t we? Do we ever say, “Why me? Why did I have food today and there are so many starving people in the universe?” Sometimes we ask that question. But very often we just take our food for granted, or we take our friends for granted, or we take the buildings we live in for granted. We take every thing we have for granted. The food offering we do at the beginning, “I contemplate how much positive potential I have accumulated in order to receive this food given by others.” That’s a reflection on karma helping us to realize that even something like one meal comes because of our own positive karma. It reminds us not to take the efforts of other sentient beings for granted, and not to neglect being generous ourselves because generosity is the cause of receiving.

Now I’m not saying we should just be generous just in order to receive food. We really want to be generous for higher purposes: to benefit others, to attain enlightenment and so forth. Yet it can be helpful on some level for us to remember that our food does come because we were generous. It comes through the kindness of others who worked very hard but it also came because of our own karmic action of being generous. If we remember that, then when there’s an opportunity to be generous we’ll take that opportunity to be generous rather than be lazy about it. That’s why I feel that it’s important to make offerings and to share things that we have in a proper way—for the benefit of others, and as a way of reminding ourselves that the happiness we experience doesn’t come out of nowhere.

Similarly when we have friendships—I think friendship is very important to all of us—or harmonious living conditions, to remember that it doesn’t come just by accident. It depends on what we do in this life and how we relate to people. But it can also depend on previous lifetimes. I remember one time—this is very cute—His Holiness the Dalai Lama was teaching about karma in Dharamsala. He was going through the ten destructive actions and one of them is unwise sexual conduct. In explaining the result of unwise sexual conduct one of the results was you have bad relationships. Your spouses are unfaithful. Of course that’s clear that it happens in this life, doesn’t it? But when we were walking away from that teaching one of my friends said, “Now I understand why my marriage didn’t work out.” In other words instead of just blaming her husband for what he did, she realized, “Hey, probably in a past life I had some unwise sexual behavior, and this caused the discord in the marriage that led to the separation.” For her that was very helpful thinking in that way. It was like, “Okay, got to clean things up and stop blaming other people.”

When we’re thinking and meditating about karma in this way, it’s very helpful to make many examples in our life. The question often gets asked, “Why sometimes do good people have unhappiness, and people who are harmful have good results?” Well, there are certain conditioning factors in this life—social systems and stuff like that. But there are also karmic things. A person who does a lot of harmful actions this life but experiences some degree of fame or wealth is consuming their good karma that they created in previous lives. They’re consuming it by having fame and wealth, but they’re also creating a ton of negative karma that’s going to lead them to unhappiness in the future.

Sometimes we see very wonderful people experiencing suffering in this life. Some of that suffering may be due to diet and external conditions, social systems, and so forth. But some of it may also be due to negative actions they did in a previous life. This way of understanding can be very helpful.

I do not recommend explaining this to people when they are in the middle of grief when they have no understanding about karma. This is not a skillful way to introduce karma to people who are grieving and who don’t have faith in cause and effect. I say this because they very easily misinterpret it to mean we’re blaming the victim and saying they deserved to suffer. We‘re not blaming the victim and saying somebody deserves to suffer. We’re just saying causes bring results and results happen because of causes. Nobody deserves to suffer, nobody is worthy of suffering. As much as possible we should do what we can to alleviate suffering.

Similarly sometimes you hear people who don’t understand karma very well say, “Well, somebody’s experiencing suffering and if I try to help them I’m interfering with their karma. So I should just let them suffer and they purify their karma that way.” I think that’s a gross misinterpretation of what the Buddha said, and a very big excuse for not being compassionate and not helping. Can you imagine somebody gets hit by a car and they’re bleeding in the middle of the road and you stand over them and go, “Tsk, tsk, tsk, poor thing this is the result of your karma. I’m not going to take you to the hospital because then I’m interfering with your karma.” That’s a bunch of hog wash.

A person who thinks like that? It just shows their ignorance of karma. They don’t realize at that moment they’re creating a ton of negative karma by being so callous to somebody else who’s suffering. To be clear, we’re not at all saying stuff like that. Then also to clarify that karma does not mean predestination. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama says, “You never know the future until it happens.” There are many things that can modify karma and can affect how things ripen.

If we look, cause and effect is such an incredible complex thing. Remember how they talk about the butterfly in Singapore that flapped its wings and it has this ripple effect that goes on and on? How our karma ripens depends on so many different things. Sometimes in the scriptures or sometimes you might hear simplistic explanations of karma saying, “Okay, if you kill, then you’re going to get killed”—black and white like that. Or, “If you steal, then your house is going to get broken into.” Like predetermined results in very black-and-white kind of thinking. But it’s not like that at all because one action can bring many different types of results. Exactly within each type of result, exactly how and when and where something ripens is mitigated by so many other factors.

I told you on Monday the story of my friend Theresa who was killed in Bangkok by the serial murderer. Well, I thought she had some kind of heavy negative karma to have her life cut off in her early twenties by being killed. But if she had not gone to this party and not met this guy it wouldn’t have happened. Or even if she met this guy at the party and she said, “I don’t like going out alone with guys who I don’t know in a strange city,” and not gone out with him, that karma wouldn’t not have had a chance to ripen. Perhaps she could have gotten to Kopan, purified it, and then it wouldn’t have ripened or would have ripened to something much less. So there are all sorts of different things that affect how something ripens.

We can notice this in our lives. When we put ourselves in certain situations, either mental or physical situations, we can see it’s much easier for negative karma to ripen. We can see if you go into a situation where there’s a lot of violence for example. Or if you go into a bar at 2:00 AM you’re going to have different karma ripen than if you go into a monastery at 2:00 AM—provided you’re not a thief in the monastery. The environment that we place ourselves in can affect what karma ripens at a certain time. Similarly what choices we make, what mental attitudes we have, what motivation we have affects what kind of karma ripens at any particular moment, and how any particular karma ripens in the whole scheme of things. What I’m getting at is we have to have a really vast big mind in terms of understanding karma and not see it as a simplistic thing. That’s why they repeatedly say in the scriptures that only the Buddha has the clairvoyant powers to see who did exactly what action when, where, how, with whom that ripened in this specific thing that happened today. Only the Buddha can say that. The rest of us are speaking in generalities as a way to help us understand principles.

It can be helpful when we’re watching television—on the few times you go watch television or go to the movies or when we read the newspaper—it can be an incredible meditation about karma. When you read these incredible things that people do, you start thinking about, “What are the karmic results of what these people in the news are doing? What kind of result are they going to experience in future lives based on what they’re doing now?” If you think about them it helps generate compassion for people who are so ignorant in that way, and it helps us really think about more specifics of cause and effect.

For example, one of the terrorists on 9/11 premeditatively going and trying to kill people. Now what kind of situation is that person likely to find themselves in the future? They may die saying, “For the glory of God” or for the glory of whatever it is. But what situation are they really going to find themselves in the future due to the ignorance and hatred that caused them to do that kind of negative act? If we think of the suffering that they’re going to experience then it can helps us have compassion for them instead of wanting to retaliate and get revenge. Both of these create more karma for us to experience bad results too.

Similarly sometimes when we read the newspaper and we see the kinds of things that people experience right now and the weird stories you read about. Then we start to think, “What kind of cause could a person have created to have this happen to them? Why in the world would that happen to somebody? They’re just walking down the road and then all of a sudden their life changes dramatically.” We hear stories like that, don’t we? Some small thing happens and the person’s life is forever changed. Well, why? Again it’s due to previous causes—positive causes, negative causes, whatever. It can be very helpful as a practical application of these general principles of karma to think of it in terms of what we read in the news.

I was going to finish my whole talk on karma today. I only got through the first section of talking about the four general principles so we’ll carry on the next time. I wanted to leave some time for questions and comments and some discussion.

Audience: I always wondered why it is that when you read about high status and definite goodness, they say that people on the bodhisattva path who are engaging in the six or ten perfections create the causes for high status with wealth and a lack of hunger. But those are the types of situations that seem to exacerbate the negative qualities of attachment and greed because you’re surrounded by wealth and opulence. Those seem like the ideal situations for people to be in power and abuse those powers and create really enormous negative karma. I’ve also heard it said that you don’t want to be born with too much wealth; you want to be somewhere in the middle because it’s better for your mind in that sense.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): So when they talk about bodhisattvas, as one result of their deeds experiencing temporal pleasure, wealth, fame, or whatever—and wouldn’t that create the cause for more defilement to arise in the mind? Let’s talk about bodhisattvas. This kind of person has generated bodhicitta. Their ultimate aim in their actions is full enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. That’s what they really care about. The side effect of their actions is that they get wealth and renown. But their motivation for doing the ten or six perfections isn’t to get wealth and renown. That’s not their motivation because that’s a very worldly motivation. Those things come as a byproduct because when you have bodhicitta if you have some wealth you can use it to benefit others. If you have some renown then people might come to hear your teachings. For bodhisattvas, even if they have those things, in their mind because they are opposing selfishness, they’re not going to use those things to generate defilements. They’re going to use those things for the benefit of other sentient beings.

For ordinary people who aren’t aspiring for our liberation and enlightenment but who motivate, “I’m going to offer lunch to the sangha because then I’ll be rich in the future.” Well, they may get richness in the future. But because they have no motivation to really overcome their attachment, that richness in the future could lead to them becoming more greedy, or more selfish, or something like that. That’s why it’s really important to create positive actions with a really good motivation. Even if people are doing something with the intention to experience a worldly result in a future life, like wealth, at least then for them to say in their minds, “When I receive that wealth I don’t want to be attached to it. I don’t want the wealth to cause problems. I want to use the wealth in order to help others and to practice.”

People have different levels of how they can practice. For some people thinking about liberation and enlightenment is just too far away. Say they have a firm belief in future lives and that’s all they want, “Liberation is for the monastics. I can’t aim for that. I’m just going to think about having a good rebirth. This lifetime I don’t have a lot of money, so I’ll give dana so next lifetime I’ll have some money.” Well, it’s certainly better than having a negative motivation and being greedy in this lifetime. There is some kind of understanding of karma and some kind of willingness to help. Still, because their motivation is for their own pleasure (even if it is in a future lifetime), that karma will only ripen in terms of their wealth in that lifetime. If they haven’t done any cultivation to eliminate their anger and attachment that wealth could lead to many problems. They could create negative karma protecting that wealth in a future lifetime or get very greedy to have more.

But for people who have a different mental capacity at that particular moment of the path, they may say, “My ultimate aim is liberation and enlightenment. That’s my ultimate aim. I’m doing this action and I want it to ripen like that. In future lives I will need food so if it ripens in terms of food I’m certainly not going to complain.” But that’s not their chief motivation and so there’s less likelihood having those fortunate worldly circumstances and misusing them. Clear?

Audience: Can I comment?

VTC: Sure.

Audience: I don’t quite believe that people get wealth; that some magical law of karma provides wealth so that they will be able to do good with it. It seems to me quite natural however if people are generous, kind, spend a lot of time and effort helping other people —so they’re really practicing a bodhisattva path—then people are thankful. When people are thankful they give things. Some give stuff: money, food, clothing. Others like governments or kings give status, they can give titles. Or in monastic systems they create elaborate hierarchical structures and some people play the power system but some people are more pure and are just recognized by those systems. For me another way to look at it is that if you’re practicing Dharma starting with generosity, kindness and all that, then people give you stuff. So those things are going to come to some extent—that’s another angle that makes sense to me. I think it’s also good or important not to take all these things too literally. I say this because those kinds of things which you brought up reflect the social conventions of that time. We see this throughout the scriptures, and we see this in Christian stuff as well, and probably other religions. Or even in the Lord of the Rings all the good women are beautiful—that’s a stereotype from many societies that the sign of inner virtue is outer good looks, wealth. There are a few ‘prince and the pauper’ kind of things, but you’re a prince, you’re a great warrior. Some of that is the literary convention to make an impression on people, and so sometimes it doesn’t have to be taken so completely literally.

VTC: It doesn’t mean that because someone is wealthy that they’re more virtuous.

Audience: That’s the problem that has happened in many Buddhist countries where the Buddhist ideal (at least in the Pali tradition) is that a king is a king because of the good karma done in previous lives. That karma ripens into many things like becoming a king. But that belief was also used to justify tyrants who were kings or had power but who were not good people. They did not keep sila [ethical conduct], they killed lots of people. They were one of the reasons Buddhism was wiped out in India because a lot of Buddhist kingdoms were filthy corrupt. So these teachings if they’re mystified can and have been used to legitimize. It’s happened in the West too, “You’re rich because you deserve it.” I think that’s a bastardization of the teachings but it’s happened a lot.

Audience: [inaudible] … a ripening of positive karma with wealth … often times the greediest people are the most destructive … [inaudible]

VTC: Well that’s the thing, in one lifetime, somebody could have created positive karma through being generous and that results in the wealth. But that doesn’t mean that that person has well-developed generosity and kindness implanted in their mind over many lifetimes that is going to automatically appear in that lifetime. It just means that they did at some point some action of generosity but it doesn’t mean that their mind has that habit of being generous.

Audience: So would you say that karma refers mostly to external circumstances? It’s almost like you’re emphasizing that quite a bit.

VTC: I think that actually where karma ripens most is upon the aggregate of feeling. The aggregate of feeling are the experiences of happiness and suffering that we have, so karma chiefly ripens on that aggregate of feeling.

Audience: Regardless of externals?

VTC: Yes. I think the external circumstances are given as an example because some people when they’re born in a situation of poverty—most people when they’re born in a situation of poverty—suffer. I think that’s an easy way for people to understand. The real way that the karma manifests is on the feeling aggregate of the experience of suffering and some people can be born poor and not suffer and it’s because of creating the cause for happiness.

Audience: Or some people suffer a lot.

Audience: Be careful. There’s some pretty good evidence that poverty as we use the word now is a relatively recent concept. For the situation I know that fifty years ago Thai farmers who didn’t have the modern concept of poverty …

VTC: What is the modern concept versus the old concept?

Audience: The modern concept has become a lot about having certain income. You’re poor if you don’t have a certain income level. You’re poor if you don’t have the trappings of modern Western lifestyle. Many Thai farmers fifty years ago didn’t think of themselves as poor. It was historically—and this has been mapped out—it was after World War II … Truman was the one who gave the speech—but when his brain trust came up with the concept of development—and divided the world into developed and undeveloped, poor and rich, first, second and third world. This was spread throughout the world and then governments like the Thai government bought into that for a variety of reasons, many of them self-centered. Then the Thai farmers were bombarded with TV images and government propaganda saying, “They’re poor.” So then they started to think of themselves as poor where as previously they didn’t—and often before that time poor was more in terms of your virtue. People spoke as much of being poor like Jesus the poverty of the spirit; you were poor if you didn’t have enough to eat and things like that, but you were also poor if you didn’t have virtue. So we have to be real careful in looking for some of our modern concepts were not operative in Buddhist countries 60-100 years ago.

Audience: But aren’t those modern concepts still a convention of karma as well? That somehow if that convention creates suffering in someone’s mind, because they never thought of themselves as poor before and now they know suffering in their mind because they’re thinking of themselves as poor, that also seems to me to be a product of some karma ripening. Something doesn’t come from nothing.

Audience: To me it’s a matter of perception. One doesn’t have to refer to past karma when one perceives their state of being as being poor, then they create suffering out of that. I don’t see that one needs to explain it in terms of past actions ripening.

Audience: But where else does suffering come from?

Audience: From their misperception.

Audience: But where would that come from? To me it just seems like it comes from the same source.

Audience: So the misperception came from government propaganda and they’re not being clear enough about causality, so they buy into the propaganda.

VTC: It could be that there are influences of both. There’s the government propaganda, but then why some people in that situation may buy into the government propaganda and some people may not. The people who buy into it suffer. So karma may have some role there in terms of why some people buy into it and why some people don’t.

Audience: Can I clarify? In the Pali tradition at least, karma is not assumed to be past lives. Karma specifically means “action,” not the results. I think the meaning has gone back and forth between the specific meaning of karma as action, but other times it’s been used in the more vaguely as “karma” which is what some people call the law of karma. I use the word karma to mean action. If we go back to the example of the Thai farmer buying into this notion of poverty, yes there were karmas involved. That farmer had thoughts, that farmer did things, that farmer said things. I can see a process of causality in this life. Causality is bigger than karma so that’s another thing. Karma isn’t the law of cause and effect. Karma is one manifestation, or the law of karma, or the relationship between the karma and vipāka [ripening or maturation of karma] is one manifestation of the law of conditionality. So yes the farmer had to make karma to buy into it, but then there are other causal factors at work that weren’t necessarily that person’s karma. You could say it was the government’s or Milton Freedman’s …

VTC: Or the media.

Audience: If people want to assume that it was karma in past lives you can, but I think it’s good to also examine the karmas that say that farmer could actively remember from the current life.

VTC: Like I was saying before it’s a very complicated system with causes coming from many different directions. So examine what’s going on this lifetime, examine what happened—conditionality from the past. Even what’s going on this life time then you could trace it to all of Thai history, and all the history of the Western countries—how we got this kind of ideology that was then imposed on Thailand. When you start looking at it from the viewpoint of cause and effect there’s just so much inter-related stuff there.

Audience: Would you say that on a personal level that our mission here is to see conditioning and karma as two influences that we’re trying to be free of? Is that what the teachings are about? That these things are sort of imposed on us?

VTC: It’s not that they’re imposed. It’s not like there’s me and then conditionality is imposed on me. I am conditionality. I don’t exist independent of conditionality. I exist only because of cause and conditions. Without them I don’t exist. When we’re talking about emptiness or nirvana, we’re talking about the unconditioned and realizing that is liberating. But then when you talk about the actions of a bodhisattva, or the actions of a Buddha, or even an arhat—an arhat’s compassion or whatever—those are also conditioned factors. All of relative existence is conditioned, it’s all dependent. In cyclic existence what we’re conditioned by is karma and klesha—klesha being the afflictions or the disturbing attitudes and negative emotions. We want to be free of that kind of conditioning, the conditioning that causes suffering. If you’re going to be of benefit and service to others that depends on conditioning too.

Audience: So being free of klesha, in and of itself, involves creating causes. [inaudible] … all those actions themselves are causal?

VTC: Right. We have to create the path and the path is a conditioned phenomenon. It’s actually an interesting thing—we shouldn’t think that conditionality itself is evil or bad. Sometimes it’s presented that way, or that impermanence is bad. Impermanence—there’s no bad or good, there’s no moral thing in it. A Buddha’s omniscient mind is impermanent because any consciousness is changing moment by moment. It’s eternal but it’s changing moment by moment. We shouldn’t think that conditionality in and of itself, or impermanence is in and of itself something that’s evil or afflicted or suffering. It’s sometimes presented like that. This world is conditionality and nirvana is unconditioned. Thinking that, “There are two realms, conditioned and unconditioned with a brick wall between then. So let’s leave this one and go across the brick wall to that one if we’re going to be of service to others.” I don’t think it’s quite like that.

Audience: I want to come back to this idea of what is a ripening effect and what is something that seems outside of a ripening effect of my personal karma. Maybe I’m seeing it too black-and-white or too fundamentalist. I wanted to know what those other conditions are.

VTC: His Holiness the Dalai Lama talks a lot about this. I went and asked him one time actually about this because sometimes in Buddhist circles they say, “Well, everything is karma.” Well, is the thunderstorm karma? Is a thunderstorm due to karma?

Audience: [inaudible]

VTC: No, it’s the pleasure that a sentient being experiences due to the breeze. It’s the feelings of happiness or pleasure that we experience due to those that are the result of karma. But the physical thing itself isn’t necessarily due to karma. This is a silly example but it serves the purpose. You’re standing under an apple tree and an apple falls on your head and goes klunk. The apple doesn’t fall because of karma. It’s not karma that makes the apple fall. But why are you standing under it and experiencing the suffering of a headache after that? That’s due to karma. Why did you happen to be there at that specific moment when the apple fell; and why does your head hurt? Maybe somebody else has a hard head and they don’t get hurt.

Audience: So could you extrapolate and say the people in the World Trade Center just happened to be there?

VTC: No. But why did they happen to be there? It’s their own actions that got them there.

Audience: They took jobs there. Some of them it’s maybe not cool to say this, but some of them were incredibly greedy people, because they were working in a very greedy industry; many of them were stock traders and bond traders and stuff like that. They chose to take jobs there. Some probably competed very hard to get some of these jobs because they’re high paying, high profile jobs.

Audience: I’m trying to figure out …

VTC: Why did the World trade Center collapse? Because steel when melted and encountering fire; that’s what happens on a physical level. What happens to steel is not karma, it’s physical causality. So the World trade Center collapsed, a physicist tells you why it collapsed and they’re investigating …

Audience: Not why but how it collapsed …

VTC: It went down. But the question of why were those specific people in that building at the time and experiencing suffering; and why were some of us outside of that building. We didn’t get killed but experienced a different kind of suffering. So within that one event there are people experiencing all different sorts of things. That’s because of individual actions that they’ve all done. And not one simple action that everybody’s done, but probably multiple actions.

Audience: Earlier you said, “Why me?” question. Ajahn Buddhadhasa felt that the Buddha’s teaching was about how suffering happens and how to get free of suffering. Human beings have the habit of asking why—which is often, “Why me? Or “Why not me?” like when we’re not getting what we want. I think that leads to a lot of confusion about these kinds of things. The broader teaching for all these things is conditionality. Things happen through causes and conditions. That’s a more fundamental teaching of the Buddha than karma. So when people jump in and try to explain everything by karma they’re getting ahead of themselves. It’s a kind of sloppy way of thinking. The starting point is to see it in terms of causality, and then within the causality there are causes that involve human intention. Some of those you can see more collectively and some you can see what other people did. But the emphasis, because karma is about how we get ourselves involved in suffering, is to look at our own actions and how we got ourselves involved in suffering. So I think we need be careful about looking at other people’s actions in terms of karma because it can easily become flippant or judgmental. You gave some examples. So we might say generally that for the people in the World Trade Center their karma got them there or something. But there’s no point in trying to pick that apart very far because we end up just blaming or something. The whole point with all the teachings is to come back to ourselves and, “Why am I still creating suffering?” The answer is because I’m doing things, and I’m doing them with intention and that means I’m doing them egoistically.

VTC: The World Trade Center; now we have such a perfect example every time something happens we use it. It’s true, we often say, “Why did this happen?” or “How did it happen?” or whatever it is. But what karma are we creating now? What conditionality are we setting in motion now by the way we react to what happened to the World Trade Center? So often we space out on that. Our government policy I think is to space out on that. But karmically in terms beyond this lifetime, the causes for what kind of results we create, we often space out on that in seeing that. There’s an event that happens that’s conditioned but our reaction to that event is more conditioning, more karma created. Sometimes we’re so focused on figuring out why that we don’t look at what our present action is. Am I explaining this well enough? Are you getting it?

Audience: Could you plan on next week, not now of course, but saying something about karmic vision? I asked you about it once and you gave a very short experience there. I would be very interested in digging into that more.

VTC: I can’t say it’s 100 percent clear for me but I can give you some of my guesses about what they mean about karmic vision. Remind me next time.

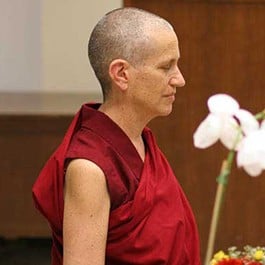

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.