Offering precepts in prison

Recently, I went to visit Michael, an incarcerated person in Ohio with whom I’ve been corresponding for over a year and a half. He first wrote to me in the autumn of 1997, expressing interest in the Heruka and Vajrayogini practices.

I wrote back, “It’s great you want to do those practices. Let’s start with lamrim.” And so we did.

Over the months, I sent him books and tapes, as well as gave him questions to think about in an effort to understand his life, his actions, and the workings of his mind. He would write sometimes quite lengthy replies, slowly opening up and gaining insights about how his mind worked.

At Dharma Friendship Foundation (DFF), people join a refuge group in which they meet and discuss the meaning of refuge and the five precepts for a few months before taking them. Michael wished to do this, and joined one of the DFF refuge groups, corresponding with the people. They all took refuge and precepts together last February: the DFF people at the center in Seattle, and Michael calling us at the appointed time from Ohio. The telephone was on the table in front of me, and two thousand miles away, he knelt on the floor beneath an open wall-phone in the prison dorm, having made a little altar with photos of the Buddha and his teachers he pasted on the phone.

He faithfully does his daily practice, which is a real refuge for him, as life in prison is not easy. He also tries to practice thought transformation in the various circumstances he encounters in daily prison life. Recently he wrote a long, touching letter about how he practices with the people he meets daily. I’ve asked him to add some anecdotes to it, and he’s given his okay for this to be shared with others when it’s ready.

Our correspondence continued, and I asked him more and deeper questions, which he answered as best he could given that letters are read and phone calls overheard by prison officials. He requested to take the eight precepts for life and responded thoughtfully to my pointed questions, asked in order to ensure he was ready to take this commitment. But how and when would the precepts ceremony be?

As things worked out, I went to Madison, Wisconsin, to study with Geshe Sopa for the summer, making it relatively easy to get to eastern Ohio where the prison is. Michael, his mother, and Randi, a volunteer leading the Buddhist group at the prison, went to great lengths to make preparations for the visit—there were paperwork, bureaucracy, and many arrangements to make, even though I would only be at the prison for four hours.

Last weekend I flew to Cleveland and was met at the airport by Randi and Michael’s mother, at whose home we stayed. The next morning Randi and I drove two hours to the prison, and after going through elaborate security, we entered the compound.

I saw Michael—6″5″ tall, with a shaven head—pacing down the walkway. His mother, sister, and the chaplain all said that he had been excited for weeks about the visit. Earlier that morning, Michael had set up altars, meditation cushions, and so forth in two otherwise stark rooms in the chapel area: one where Randi would meet with the Buddhist group and the other where Michael and I would be.

It was simultaneously familiar and strange to meet this person that I felt I already knew well. Michael had prepared several offerings—goodies he had bought from the prison commissary, wrapped in white handkerchiefs, and offered to me respectfully. Randi had brought him a kata, which I showed him how to fold and to offer, and he did.

After making offerings to the Buddha, we talked for about two hours, and he related to me some of the things that he could not previously say or write. It was a “splitting open of negativities,” which he did earnestly and trustingly, and which I listen to with similar attitudes. Just as we began to do Vajrasattva practice, someone in another room turned on incredibly loud music. But we continued as if nothing happened: that was the only time we had to practice together and it was already very short, so we just did it. Having completed Vajrasattva puification, we did the precepts ceremony, and Michael formally received the eight precepts, including celibacy, for life.

He had been able to arrange for me to give a talk to the Buddhist group, something not usually allowed on a private clergy visit, so we joined Randi and the others in the next room. There the men asked me, among other things, about working with anger, the meaning of enlightenment, how to practice daily, and why I chose to become a nun. When the chaplain gave us the times-up signal, we quickly ended. As the men left, they smiled happily, bringing me much joy: if I could bring some happiness and clarity to people in these circumstances, my life was worthwhile.

Michael called us at his mother’s that evening, and I asked him how he felt. “Very clean inside,” he responded. Trust has built up over the time we had corresponded. He trusts the Dharma and the guidance he receives, and I trust him to look hard at difficult issues and to put what he learns into practice.

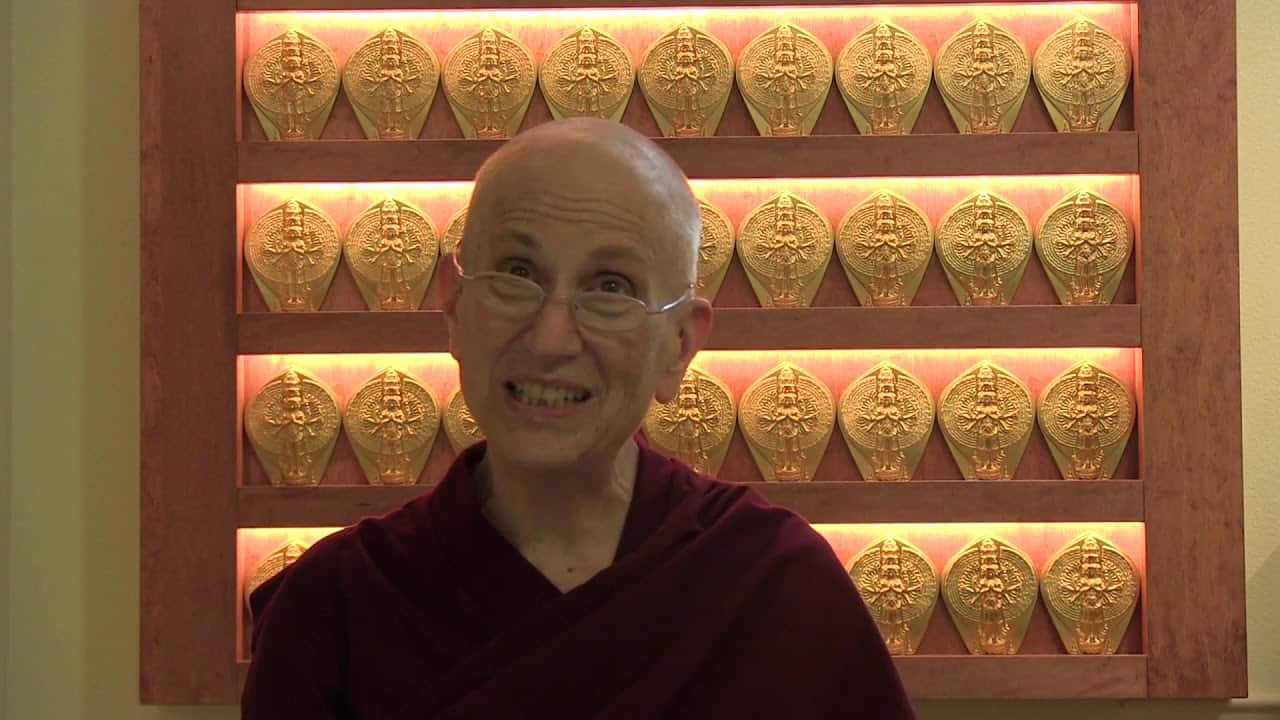

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.