Some challenges of changing religions

Some of us come to Buddhism having been brought up in another religion. The conditioning we received from our previous experiences with religion or religious institutions affect us. Being aware of this conditioning and of our emotional responses to it is important. For example, some people were brought up in religions with a great deal of ritual. Due to personal dispositions and interests, there’s a wide variety of responses to this. Some people love ritual and experience it as soothing. Others find that it doesn’t suit them. Two people may experience similar situations or live in the same environment, but due to karma and to their personal dispositions, they may experience these very differently.

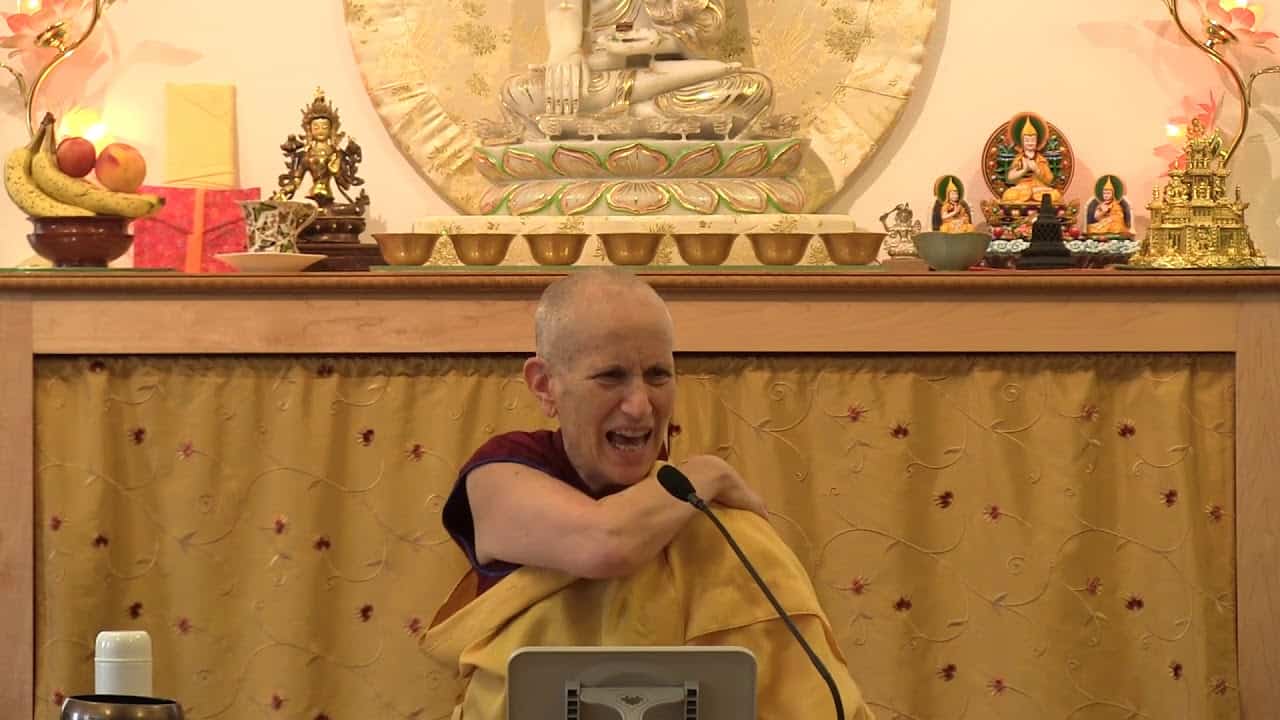

The conditioning we received from our previous experiences with religion or religious institutions affect us. (Photo by Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston)

There is nothing inherently good or bad about ritual. The quality of our response to it, however, is important. Some people become attached to rituals or thinking that the mere performance of a ritual is sufficient. Others greet ritual with aversion or suspicion. Either way, the mind is bound up in emotional reactivity that impedes spiritual progress.

Clarity that comes from introspection is needed. Reviewing our past experiences with ritual is the first step. What were our previous experiences? How did we react then? Were we reacting to the ritual or rather to being forced to sit and listen to it when we wanted to do something else? What really are our issues with it? This type of reflection is extremely beneficial for making conscious what our actual issues are. Once we can identify the issues, it’s possible to look at them more clearly and ask ourselves, “Was my reaction at that time appropriate? Was it the response of a child who couldn’t understand what the adults around him or her were doing?” Then we can reflect, “Is my current response based on clarity or bias?” In this way, we can bring to light our previous conditioning, observe and be understanding of our responses to those experiences, be aware of our present responses, and then choose what is reasonable and beneficial given our personal disposition.

It’s helpful to look at other events in our early exposure to religion as well. For example, perhaps we are very skeptical of organized religion, believing it to be corrupt, manipulative, and damaging. What conditioning were we exposed to previously that led us to that conclusion? Perhaps as children we saw adults saying one thing in church and acting in another way outside of church. Perhaps, as students in school, we were scolded by those in positions of authority in the church. How did we react? It could have been with disdain in the first case or with rebelliousness in the second. Then our mind made a generalization: “Everything that has to do with organized religion is corrupt and I don’t want anything to do with it.”

But looking a little deeper, could that generalization be a bit extreme? It’s helpful to distinguish between religious principles and religious institutions. Religious principles are such values as love, compassion, ethical conduct, kindness, tolerance, wisdom, respect for life, and forgiveness. These principles and the methods to develop them were described by wise and compassionate people. If we practice them and try to integrate them into our minds, we will benefit, as will those around us.

Religious institutions, on the other hand, are ways of organizing people that were developed by human beings whose minds are obscured by ignorance, hostility, and attachment. Religious institutions are by nature flawed; any institution—social, economic, political, health care, and so forth—is imperfect. That doesn’t mean institutions are totally useless; all societies utilize them as ways to organize people and events. However, we need to find a way of working with institutions that brings the most benefit and causes the least harm.

Being aware of the difference between religious principles and religious institutions is crucial: The former may be pure and admirable, while the latter are lacking and sometimes, unfortunately, even harmful. That’s the reality of cyclic existence, existence under the influence of ignorance, attachment, and hostility. Expecting religious institutions to be totally pure simply because religious principles are uplifting is not reasonable. Of course, as children principles and institutions may have been mixed together in our minds and thus we may have rejected an entire religious philosophy because of the harmful actions of a few people.

During retreats, we sometimes have discussions with people breaking into groups according to their religion of origin. I ask them to reflect:

- What did you learn from your religion of origin that has been helpful to you in life? For example, were there certain ethical values that you learned from it that have helped you? Did some people’s behavior inspire or encourage you? Let yourself acknowledge and appreciate these positive influences in your life.

- What experiences did you have with your religion of origin that conditioned you in a detrimental way? If you harbor resentment, trace its development, examining not only the external events but also your internal responses to them. Try to understand the development of these negative emotions and let them go. Find a way to make peace with those experiences, learning what you can from them while at the same time not letting them control your life or make you unable to see the goodness that comes your way.

The result from such reflection and discussion is healing. People are able to have a more comprehensive and balanced view of their previous religious conditioning and are able to appreciate what is valuable and let go of resentment about what wasn’t useful. With their minds clearer, they are then able to approach Buddhism with a fresh attitude.

Another challenge of becoming a Buddhist after being raised in another religion is mistakenly interpreting some Buddhist words or ideas as having meanings as in our previous religion. Here are some common misinterpretations people form:

- Relating to the Buddha as we would to God: thinking the Buddha is omnipotent, thinking we need to please and obey the Buddha to avoid punishment

- Praying to Buddhist meditational deities as we would to God

- Thinking karma and its effects are a system of reward and punishment

- Thinking that the realms of existence spoken of in Buddhism are comparable to heaven or hell as explained in Christianity

- And many more. Be aware of these when you discover them in yourselves. Then contemplate what the Buddha said about these topics and be aware of the differences.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.