My prison education

By R. C.

Ron has been in prison for over 25 years for a murder he committed as a teenager. He is a model imprisoned person now, making videos for the Department of Corrections in his state and teaching classes on Impact of Violence on Victims and Criminal Thinking to other incarcerated people. Venerable Chodron asked him what is the foremost thing he has learned while incarcerated.

The biggest lessons I’ve learned are about empathy; how to cultivate it, how I define community, what is my place in it. I should probably start this elaboration with a slight clarification: When I said “learned,” I probably more accurately mean “learning.”

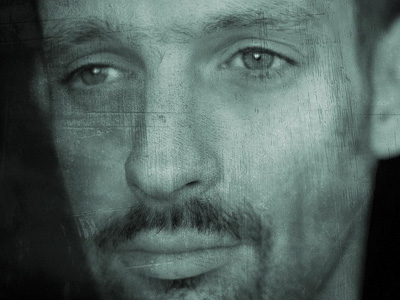

Not only is empathy something to be learned, but the process of cultivating it is a painful, uncomfortable one. (Photo by Merrill Leo)

A lot of my learning is based on listening to conversations in a classroom setting, either Impact of Crime on Victims classes or the class on Criminal Thinking. Many times people think empathy and sympathy are the same thing. Many class participants have only a casual or superficial understanding of empathy. It seems like it’s some easy thing or something that’s taken for granted that everyone does, like being able to talk. But people forget that they had to learn how to talk. My opinion is that not only is empathy something to be learned, but the process of cultivating it is a painful, uncomfortable one. For me, empathy has to do with really experiencing another person’s suffering–as much as one person to another can–opening up to someone else’s pain. It can be an awful lot to ask, and it would be enough for some people to open themselves up just enough to say, “I feel your suffering.” I would liken it to standing in a strong wind with someone.

Empathy should be like trying to stand up in a tornado instead, especially if the suffering of the person in their experience is like a tornado, metaphorically speaking. This is not an intellectual consideration; this is a deliberate attempt to get as close as possible to what that person is experiencing. That’s why it is such a painful, uncomfortable thing to do, to be empathetic, and empathize.

If you can open yourself up to another person’s suffering, you are quickly motivated to alleviate it. That’s what I mean by empathy. For me, the dynamic of talking to families who have endured the murder of a loved one has been a powerful motivation to cultivate empathy, especially when I draw a parallel between what happened to them and what I did. In my limited understanding of the four noble truths, it seems to me that you have to look directly at suffering before you progress to an alleviation of it. The cultivation of empathy means always being open to another person’s suffering, however painful it may be, because you can respond compassionately. I don’t know what it’s like to be a refugee from another country, but it’s important for me to approximate their feeling, to feel their hardship as much as possible. We should do the same with any person, so you can move forward with a compassionate solution.

Many times after listening to these same families who’ve survived a loved one’s murder I’ve asked them if talking about their son/husband/daughter/mother/ etc. to a room full of strangers has helped them. I have never heard any of them say anything other than “oh yes,” usually emphatically. That response has renewed my efforts to work with restorative justice on many occasions. It helps those families to know that they can talk openly about these tragedies to people who are not only listening, but are actively listening, not to mention opening themselves to the pain of such loss.

All of that shapes my definition of community. I want my community to be empathetic. I want my role in it to be one of service, “How can I help you?” It seems to me that that is how one becomes a bodhisattva, to move with active compassion to alleviate suffering. To me it means less to stand in the midst of that tornado, unless to do so is to help another person. Tonglen, the Buddhist meditation of imagining taking others’ suffering and giving them happiness, is probably a perfect example of what I’ve tried to describe.

Read R. C.’s journal on the first series of classes he attended.

Read R. C.’s account of his experience meeting victims in person as part of the Impact of Crime on Victims program.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.