Scars and catharsis

By R. C.

An account of the Impact of Crime on Victims program, which brings together incarcerated people who have committed a crime and victims of similar crimes so that both can learn, grow, and heal.

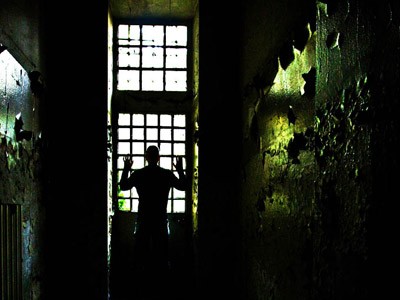

At about 12:30 in the afternoon, after one last morning filled with anxiety, a corrections officer calls over the intercom for the eight of us to go to the visiting room. Once there, we change from our personal clothes, mostly t-shirts and sweat pants, into standard dress-out clothes: grey canvas pants with only an elastic band to secure them and white button-up shirts, stiff from too much starch. Then, we wait. Some of the men smoke cigarettes just outside the door while others engage in a light banter that sounds forced under the circumstances.

Hands, the hands of men convicted of vicious murders in Missouri courtrooms, are shaking. Finally, after nearly an hour of our own private thoughts and fears, we receive a call instructing us to enter a prepared classroom. Time to face the victims …

The class on the Impact of Crime on Victims originated as a joint effort between the California Youth Authority and Mothers Against Drunk Driving. The state of Missouri adopted the program statewide for its bulging prison system. In August 2000, a group of men incarcerated at the Potosi Correctional Center participated in the initial two-week, forty-hour trial program which culminated in an emotionally charged visit with the victims of various crimes. Thanks in part to enthusiastic support of the initial group, interest in the class has flourished. Now, more than one hundred men in this prison have completed the class. I am one of those men. The following report is based on my experience in the class. Out of respect for their privacy, the names of Impact Panel members have been changed.

In October 2000, nine of us entered the classroom on a Tuesday night; no man among us had a conviction of less than second degree homicide. The majority of us, myself included, were serving sentences of life without parole for first degree murder convictions. We came with notebooks and pens; our intention was to learn. The class took place three or four nights a week for two weeks, four to six hours a night, so it was fairly intense. At each successive meeting, all of which lasted well past the scheduled four hours, we received a stapled lesson packet and watched a video on each of the following topics: property crime, drugs and society, drunk driving and death injury, domestic violence, child maltreatment, assault and sexual assaults, victims of gang violence, violent crime, robbery and homicide. The facilitators, three or four members of the prison staff, encouraged open discussion and it didn’t take much for everyone to get involved. After these classes, we were to meet with the families of crime victims – not the victims of our particular actions, but those who had suffered similarly at the hands of others.

The consensus expressed by the imprisoned participants during these discussions, both discussions amongst ourselves and those with the families of victims, contradicted much of what is commonly believed about convicts doing time in a maximum security prison. Many of the men in that room will never see the outside again. They spoke with absolute candor, which took the form of ideas anyone else in our society might express: the drastic need to reduce crime, especially its escalation among juveniles and approval of police interventions. For these men, a desperate need for atonement and a deep sense of regret for past deeds motivated them to volunteer for the class.

Much discussion stemmed from the deft handling of each night’s topic by the facilitators. The videos provided the emotional impact. Understanding how the effects of crime ripple outwards like concentric circles—from a decline in the victim’s physical and mental health to increased financial burdens, to the effects on the larger community—carried its own educational and moral value, but witnessing the real human face of agony affected us on an even more profound level. Crime does not discriminate on the basis of gender, social strata, culture, or race. Each video presented an unflinching realistic look at people who are suffering the consequences of it.

When robbers invade one mother’s home, she has to choose which son to protect. A six-year old girl begs a 911 operator for help while her father murders the rest of the family one by one, audibly in the background. While one mother mourns the death of her daughter, an inadvertent casualty of gang retaliation, another mother has to endure the indignity of her son’s funeral being dominated by the members of his gang. A son seeking answers to his mother’s death finds his resentment deepening during a meeting with her killer; while in another prison visiting room, a man extends his hand in friendship and forgiveness to his assailant. Although poignant, these videotaped stories could only convey to us an inkling of what actually meeting crime victims would be like for us.

On the fourth night of class, our group shrunk to eight. To paraphrase the man who dropped out, “It was more than I bargained for.” The unadorned honesty of this class intimidated many men. In fact, some liken the experience to a court hearing. Perhaps this man foresaw the intensity of the moment when we would meet victims face to face. True, the facilitators, who we considered fellow participants, helped prepare us, but that wouldn’t make the visit any easier.

Then, the Saturday afternoon came, when after 40 hours in the classroom and a morning filled with private thoughts and fears, we met the victims. Our facilitators, along with the assistant superintendent and the prison psychologist, had arrived before us. The desks in the classroom, usually set in a horseshoe pattern, were now arranged in two rows facing one another. We sat in one row, a fairly young culturally diverse group. The panel of victims silently entered a door and sat down directly across from us. Also culturally diverse, they presented a greater age range and were mostly female. One by one, they told us how violent crimes had shattered their lives.

Kevin’s parents began. Both were middle-aged and had quiet demeanors. Kevin’s father described coping with the loss of Kevin to an apparent highway accident, only to learn later from the mortuary that shotgun pellets were discovered in Kevin’s head during the preparation of his body for the funeral. The police could find no motive for his murder.

Two women followed. Bonnie was twice a victim of rape at the hands of acquaintances. Sheri was a victim of incest when she was a young girl and of gang rape later in her life. Bonnie’s husband provided gentle unspoken support with his presence. Sheri relied on her own diamond-hard anger and admirable will. “I do not consider myself a victim,” she stated. “I consider myself a survivor.”

Trish and Carol then shared how their sister was discovered drowned in the bathtub, murdered by her own husband. The legal proceedings over the murder were frustrating and difficult. Then they described how the husband is challenging them over the right to mark their sister’s grave. He continues his efforts to block them from doing so from behind penitentiary walls, where he is serving a sentence with possible parole.

Eighteen years after the murder of her daughter, Ellen still feels the loss. She works closely with families of murdered members and heads up the Impact Panel. Ellen shared how a stranger abducted her daughter from work, raped and then killed her with a tire iron. Ellen and her husband discovered the body. The white hot pain still lives in her, but Ellen has channeled it into efforts to improve the often ignored rights of victims. She works to promote tougher laws with longer sentences and to keep better track of perpetrators who sometimes slip through the legal system due to errors, as did her daughter’s killer.

The simple straightforward manner in which these people recounted their tragedies delivered the real impact. Despite certain similarities they had—universal pain, frustration and adjustment to the sudden void where a loved one once existed—the individual loss for each speaker stood out with clarity. Maybe we could not fathom just how deep that void was, but we certainly felt sorrow for these courageous people, who shared their personal suffering with a group of convicted felons. “Now,” Ellen said, “tell us why you are here.”

She was asking not why we were incarcerated, but why we had come to the Impact of Crime on Victims program. This was the only real statement put to us, so most of our responses didn’t go into much detail regarding the events leading up to our imprisonment, though participants in some cases certainly elaborated, but instead focused more on getting an idea of the victims’ perspective or expressing sorrow for the crime we committed.

Every man responded with obvious difficulty. The small glimpse into the private hell that these people endure every minute, hour, and day triggered profound reactions in us. Compassion rose up naturally among us in the face of their naked suffering, but serious introspection came with reluctance. We had preyed on, taken away, and destroyed others’ lives, and we had to live with the awful truth of these selfish past deeds. Staring into honesty so bright can be a shock to the system. I understand now why some men refuse to sign up for this program. Still, the level of the honesty was incredible, and some told of their own victimization in prison.

Prisons condition already apathetic people to care even less, but caring is what makes us human. Inside that classroom, I felt I cared. And it hurt. I felt not only the pain of lives taken from loved ones, but the sometimes overwhelming burden of my regret. I felt so ashamed of myself. Maybe I didn’t have the family of the person I killed before me, but these men and women had experienced similar losses. I couldn’t tell my victim’s family how sorry I was, but I was compelled to tell this group of people who deserved so much more than an apology. Each man expressed similar sentiments to the panel, not as pleas for forgiveness, but as admissions of honest sorrow in tears.

Buddhists refer to sangha or spiritual community. Sangha arises when people come together for a greater purpose, an awakening of the sacred. For those involved in this program—prisoners, victims, and families—healing and humanity are the greater purpose. No one embraced afterward, but a change in the atmosphere filled the room. Does this program help speed the healing process for these wounded families? Many members I have talked to say that it has. As we prepared to leave that day, Bonnie’s husband told us, “If what you said is sincere, then you’re obliged to make a difference. Take what you feel back into the prison and help prevent violence.”

Customarily, after this meeting, there is one follow-up meeting with the families of crime victims, and it has a much different dynamic. Whereas the initial meeting is really intense and doesn’t feature a lot of dialogue—mostly one side speaks, then the other—the follow-up is more about sharing back and forth on both sides. Personally, I’ve made an effort to continue to meet with some of these families and have seen many of them up to a dozen times or more. It has been a way for me to give back to society.

Though this program could not happen as anything less than a true collaborative effort with victims from the community and people behind bars, the words here can only express what the program means to me. It gives me a reason to live after robbing someone of their life. I can do nothing to replace that life, but this program provides a way for me to give back something of what I have taken. This program can reach more than just incarcerated people. Anyone can lose their humanity. Anyone can lose a loved one to crime. The trick, which lies at the heart of this class is to feel it. Feel for your neighbors. Show compassion for your fellow human beings. Simply feel.

A few years later

The staff for Impact of Crime on Victims trained some of us incarcerated people to be facilitators for new groups. We were also able to revise the curriculum. Several years later, we had a chance to use the curriculum we wrote in its entirety and to run almost every aspect of the class ourselves. We were in many ways breaking new ground for the program. Another first was that this was a protective custody group, and we were all in general population—policy says that the two should never come into contact—so I thought it was awesome that they trusted us to do this.

This was probably the single best class I’ve ever been in, and in a lot of ways the hardest. It was a definite challenge for me to hear some of the things I heard. The level of honesty in this group was completely open from almost the first night of the program. The fact that they opened up like they did to us, a relative group of strangers, was a real privilege. I never thought I would see the day where I would sit in a room in a level five, maximum security prison and cry unabashedly with my head on another man’s shoulder from hearing about the suffering in his life. It was such a growing experience for me and for all the facilitators.

Although I was not the main person who facilitated this class, I did have a moment to speak. For many years, it has been a luxury to not have to talk about the life I took, and I think that in many ways, I’ve deliberately tried to put distance between the present moment and the man I am today and that moment and that teenage boy I once was. My reason for that, I believe, was a way of saying that person wasn’t me, even though I recently wrote a letter of apology to my victim’s family. I feel that I have always taken responsibility for the crime I had committed, but if the topic didn’t come up, that was fine with me.

During the homicide chapter in this class, I stood up in front of everyone and told what I had done and how many people I had hurt by my actions. It was so difficult, but in a way very liberating. The acknowledgement of what I had done and the fact that I could see just how many people I had hurt was a necessary part of my growth as a compassionate being. I believe it is important for the facilitators to be wiling to speak up and take responsibility for their actions so that participants will be more likely to do the same and will be more willing to look at how their actions affect others. Sometimes it’s easy for me to lose sight of what goes on in this program, seeing only the participants as the students who learn from it. But I experience constant growth through this program if I am mindful.

Dedicated to S. N.

Read R. C.’s journal on the first series of classes he attended.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.