Prologue

From Blossoms of the Dharma: Living as a Buddhist Nun, published in 1999. This book, no longer in print, gathered together some of the presentations given at the 1996 Life as a Buddhist Nun conference in Bodhgaya, India.

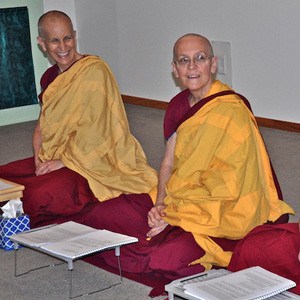

An important chapter in the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings to the West is the development of a Buddhist monastic community. (Photo by Sravasti Abbey)

An important chapter in the transmission of the Buddha’s teachings to the West is the development of a Buddhist monastic community. The Three Jewels to which one goes for refuge as a Buddhist are the Buddha, his teachings (Dharma), and the spiritual community (Sangha). The latter traditionally refers to the ordained community of nuns and monks. While the sangha has been the center of the Buddhist community in traditional societies, its role in the West is a work in progress.

A small number of Western Buddhists have chosen to ordain as monks and nuns. Giving up the householder life, they take a precept of celibacy, shave their hair, don monastic robes, and enter into what is, in most Buddhist traditions, a lifelong commitment in which their daily activities are guided by the system of precepts know as the Vinaya.

Theirs is a challenging undertaking. On the one hand, they take on the full measure of the Buddhist teachings, accepting the definition of a full-time practitioner offered from within the tradition itself. On the other hand, as Westerners, they enter into a monastic system which has until recently existed only in Asian societies, where the Dharma and the culture are intricately interwoven. In addition, the precepts that guide and structure their lives originated during the time of the Buddha, more than twenty-five hundred years ago. Many of these rules are timeless and relevant; some are difficult to abide by in the modern age. Naturally, questions of modernization and adaptation arise.

Western monastics also face the challenge of entering into a life in which no readily available “slot” for them exists. Buddhist cultures have a place and an expectation for the nuns of that culture. Without addressing the question of whether or not Western women want to fit into that slot, the fact is that it is not easy for them to do so given the great differences of background, language, and culture. And Western society does not yet have a slot for them. Its expectations of monks and nuns are largely shaped by the Catholic tradition, which differs in many ways from the Buddhist one. Thus, Western nuns must live creatively, often training in an Asian cultural context and later living in a Western one.

Finally, for women, another set of challenges is present. Although many people can and do make the case that Buddhism is at heart an egalitarian religion in which women’s equal potential for enlightenment has never been denied, the actual situation of ordained women has, more often that not, been far less than equal. In fact, in many Buddhist countries women do not, at this time, have the opportunity to receive ordination of the same level as that of men, although such an ordination for women has existed since the time of the Buddha. An important movement in the Buddhist world to change this situation has been spurred in large part by the interest and work of Western women.

This books comes out of a conference at which women from around the world, representing a variety of Buddhist traditions, met to grapple with these issues, to find ways to refine and improve the choices they have made, to encourage each other, and to become a sangha. What shines through in these pages is the power and force of an ordained life, the fact that despite the difficulties—and for this pioneer generation of Western Buddhist nuns, there are many—the life they have chosen offers a clear and meaningful path of full-time commitment to spiritual endeavor.

Having that choice is important. From their own side, women need the opportunity to choose to devote their lives to spiritual rather than worldly pursuits. In our excessively materialistic culture, the existence of a visible counterbalance is critical. The presence of those who have chosen to live in a way focused on the aims and values of the spiritual, rather than the material, both confronts and inspires society as a whole. This book offers a meaningful window into their pioneering world.

Elizabeth Napper

Elizabeth Napper, PhD., a scholar of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism, is author of "Dependent-Arising and Emptiness", translator and editor of "Mind in Tibetan Buddhism", and co-editor of "Kindness, Clarity and Insight", by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. She is co-director of the Tibetan Nuns Project and divides her time between Dharamsala, India and the United States.