Developing a relationship with Vajrasattva

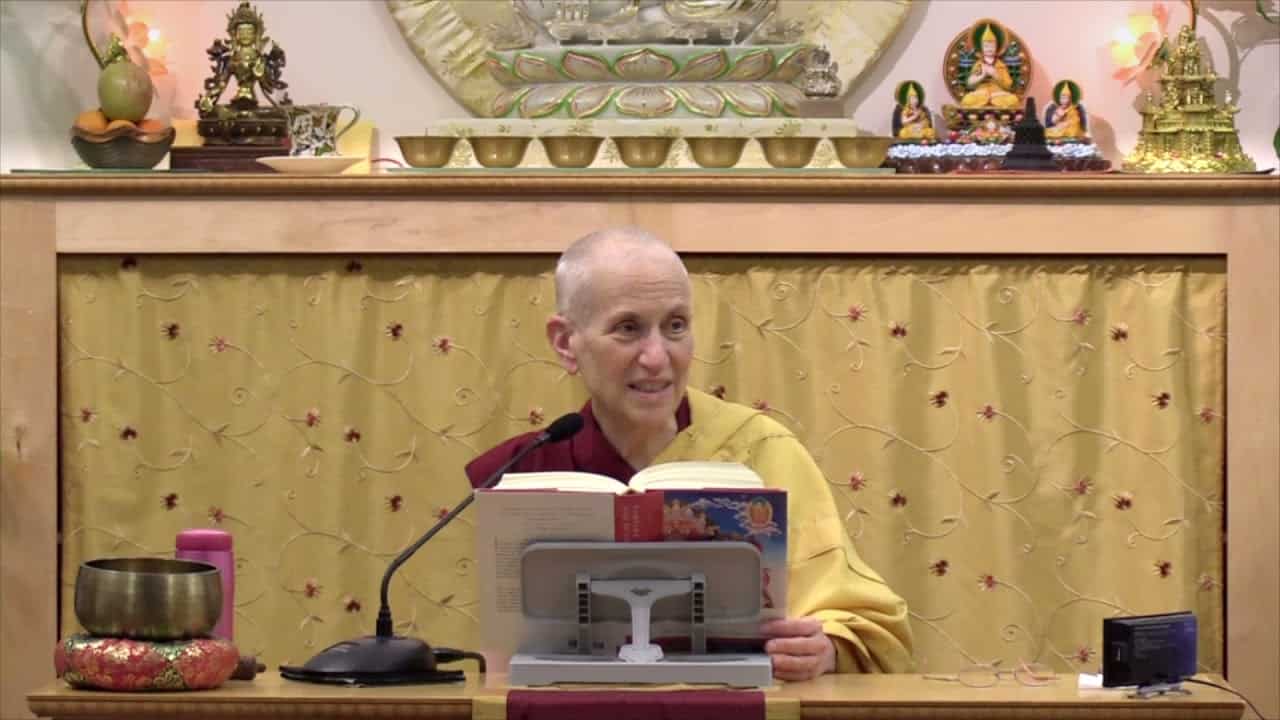

A talk given during the 2022 New Year’s Vajrasattva Purification Retreat at Sravasti Abbey.

Happy New Year, Happy Old Year—what makes this a new year? It’s just our mind. If you didn’t have a calendar, you wouldn’t know what day was New Year because all the days are the same. So, we might as well make all the days good days.

We’re here to have a little vacation with Vajrasattva over the weekend. Vajrasattva is actually all around us, even physically. You can think of all the snowflakes as small Vajrasattvas, and if we get snow today and tomorrow, just think of Vajrasattva like in the Sadhana. You can think of all the snowflakes coming in your body and purifying. They’re going to come outside your body, but it’s the same idea of purification. It is a nice way, really, to remember the practice when you’re going around doing your daily life activities. Even when you put salt or sugar on your food, you can think, “Vajrasattvas.” [laughter] It’s very helpful. It sounds funny, but it reminds you of the Dharma, and that is always very useful to our minds to be reminded.

It’s now 2022. Last night, New Year’s Eve, people got very excited, and today they slept late and will watch football games. And we’re still in samsara. So, New Year or no New Year, samsara continues on. What propels it is the ignorance, the afflictions, in our own mind, and the karma that we create due to them. Again, New Year or no New Year, if we want happiness, we have to counteract the ignorance and the afflictions. There is no way to sweet talk them into leaving us alone. There is no way to appease them so that they back off. We have to see them clearly, know them for what they are, and—wishing for our own happiness and the happiness of others—not follow them. Saying the words is easy, but we need some help in actually doing it, and this is where Vajrasattva comes in.

But Vajrasattva doesn’t say, “Oh yes, I’ll take care of it all for you.” He says, “If you want my help, the first thing you have to do is have the aspiration to take care of all other living beings because that’s the dearest thing in my own heart.” So, let’s generate that bodhicitta attitude that wants not just to take care of sentient beings suffering in this life, but wants to do whatever we can to help free them from samsara and help them to attain full awakening. Let’s make that our motivation for this weekend and for our entire life.

Taking refuge in Vajrasattva

I was reading someone’s request to take refuge, and one of the first questions that was asked was, “What do you usually take refuge in?” And the person answered, “My partner.” I think that’s pretty common in samsara to take refuge in our partner or another family member or a best friend. We think that person is the one who will protect us, who will always be there for us, but that person is impermanent. Their mind is under the influence of afflictions and karma, and we already know that whatever comes together must separate. So, taking refuge in other samsaric beings is not going to really fulfill our need. That’s why we turn to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and, especially in this retreat, to one manifestation of the Buddha’s omniscient mind: Vajrasattva.

Vajrasattva is going to be a much more reliable friend. He’s not moody. Our regular friends are moody, aren’t they? You’re never quite sure what you’re going to get when you meet them each day because they may be in a good mood, or they may be in a bad mood. Vajrasattva’s mood is quite constant, and his attitude towards us is always one of keeping our best interests, and the best interests of all living beings, in his heart. When ordinary beings approach us, there’s always a little bit of attachment: “What can they get out of us?” and “What can we get out of them?” Whereas with Vajrasattva, he’s not trying to get anything out of us, not even those tangerines and apples that we offered on the altar. He doesn’t care about that.

If we miss his birthday, he’s not going to cry. If we miss our anniversary of learning Vajrasattva practice, he’s not going to accuse us of being unfaithful. So, establishing a relationship with the holy beings is quite important in our own life. We’re the one who is responsible for doing that. And how do we establish a relationship with the buddhas and bodhisattvas and meditational deities? It’s through our practice. That’s the way we establish the relationship.

We may think of it as, “Oh, I’m doing this practice as something outside of myself that I’m doing,” but we are actually establishing a relationship with a buddha. There is the external buddha that Vajrasattva is, a being who attained awakening in the form of Vajrasattva, and actually there are many beings who attain awakening in the form of Vajrasattva. But we’re also connecting with the Vajrasattva that we are going to become in the future.

And so, that Vajrasattva is the culmination of realizations of a buddha that we want to have in the future, and that we’re creating the causes to have right now. Turning to Vajrasattva for refuge is also turning to one part of ourselves that we very often ignore or don’t appreciate. And we’re learning to establish a relationship with that part of ourselves that has really noble aspirations, that has wisdom, that has compassion. These attributes are still in their baby phases in us now, but we can make them grow through establishing the relationship with the external Vajrasattva who is already enlightened and the Vajrasattva we will become in the future. Those are two ways that we can think of Vajrasattva—as an actual being and as the Buddha we will become.

An embodiment of excellent qualities

Another way to see Vajrasattva, which is very helpful, is to see Vajrasattva as the embodiment of all the excellent qualities. Seeing Vajrasattva that way—as a collection of excellent qualities—helps us to avoid grasping Vajrasattva as inherently existent. Because we tend to see other people as if they were real: “Okay, there are their qualities and their body, but then there’s a person there, a real person.” And actually, there are just all these qualities, and in dependence on these qualities, the name “I” or “person” or “Vajrasattva” or whoever it is, is imputed. But there is no separate person somewhere mixed in with those qualities, mixed in with our psychophysical aggregates.

If we practice seeing Vajrasattva as the embodiment of these qualities, and really focus on what the qualities are—and then understand the name “Vajrasattva” is imputed on that basis of imputation—then that helps us to avoid grasping inherent existence. And it helps us avoid thinking of Vajrasattva as some kind of god, especially those of us raised in a Judeo-Christian culture where there is some supreme being out there, and your job is to propitiate that being—to please them and so on. Then they judge you and determine what happens to you. Vajrasattva is not like that.

So, we have to be very clear when we’re meditating on Vajrasattva; don’t confuse the Judeo-Christian notion of a god who’s a creator, and the controller, and the manager of the universe with Vajrasattva who is a buddha. These are two different concepts of what a holy being is. This is quite important, because if we confuse it and think of Vajrasattva as God and pray to Vajrasattva like we used to pray to God when we were kids, then do we really understand what the Buddha taught if we have that kind of way of relating to the buddhas and other holy beings? We want to really shift that, and understand there is a merely labeled person, a merely designated Vajrasattva. But when you search for some real person that he is, there is nobody there.

Who is this “I?”

And that is how we exist, too, despite the fact that we feel like there is a real “me” somewhere floating around in here. We feel like there is that “I,” but when we search for what the word “I” refers to, what are we going to find inside our body and mind that is what the word “I” refers to? You can see that I-grasping very clearly when we get into thinking, “I want to be happy. I’m so tired of suffering. I want happiness.” Do you ever have that desperate feeling of, “I want happiness?” It feels like, “I can’t stand this suffering. I want happiness! I can’t stand suffering!” And at that point, the “I” feels so real, and it’s so big it feels like it even goes beyond our body and it just consumes the whole universe, reverberating with “I WANT HAPPINESS!”

But when we question who that “I” is, what are we going to point to? There is a person there, but we can’t find it. And there is Vajrasattva there, but we can’t find Vajrasattva with ultimate analysis, so it’s this combination of emptiness and dependent arising. There is a dependently arising Vajrasattva, but it’s empty of an inherently existent Vajrasattva. And it’s the same for us. There is a dependently arising “me,” but there’s no inherently existent “me.” Yet, we still feel like there is an inherently existent me because we wonder, “If I’m not all that stuff, then what am I?” Then you see, we go to the extreme of nihilism. We go from grasping an inherently existent “I” to saying, “Well, if that doesn’t exist, then I don’t exist.” We flipped to nihilism.

But you do exist. You know, we’re sitting here in this room, aren’t we? We exist. We just don’t exist in the way we think we exist. But we tend to go from the extreme of, “There is a real me, I’m sure of it, and I want what I want when I want it, and I deserve it, and everybody should do what I want otherwise I’m going to freak out!” There is that one, and when we search for it and don’t find it, then we flip to the other extreme of, “Then I don’t exist!” And then we freak out even more, “I DON’T EXIST!” But that is the empty inherently existent “I” screaming, “I don’t exist!” And then this feeling of terror arises if “I don’t exist.” But both of those are extremes; neither of those are the way things actually are.

It’s helpful to come back to remembering that there is a collection of qualities, and, in dependence on those, Vajrasattva is designated. Same with you—there is a body and mind here, and in dependence on those, “I” is designated. But we can’t leave it like that; that self-grasping is quite sneaky, so we have to keep working at it, keep reminding ourselves, and watch when it comes up during the day. Because there is not only “I” but also there is “mine.” So, “mine” is kind of the aspect of: “It’s an I. It’s a person—that makes things ‘mine.’” But then we see other things as “mine,” and if those other things are people and something happen to them, then that ‘I” becomes very strong.

The suffering of “MINE”

I love MY kitty–actually all four kitties. But I love them in order of the one who pays the most attention to me and not the one who scratches. I have to admit it. And I love MY family, and I love this thermos—I take it everywhere with me. It’s so useful. Who wants to be caught anywhere without a thermos?” [laughter] Every time I sit down here, the first thing I do is pick up the thermos and take a drink: “MY thermos, mmm.” And MY book. MY clothes. MY house. All of Sravasti Abbey is MINE. MINE. Okay, we share it, but it’s really MINE. [laughter] And I should be able to govern everything that happens in it, not you! [laughter]

So, whenever something that we consider MINE is threatened or something happens to it, the sense of I we have comes up very strongly. “The kitty who usually purrs scratched me!” Or, “She died! Oh no!” Or, “My house burned down!” Now, some of the people who have actually had this happen to them in this life are going to say, “Stop making fun of us.” I’m not making fun, okay? I’m trying to make some examples of how that “I” manifests in our life and how—through attachment to that I and seeing that I as more important than anything else—we suffer.

When other people get scratched by their kitties, when their pets die, I do not get so overwhelmed with misery as I do when it’s MINE. In Colorado there were just horrible fires and many people lost their homes. I think over ten thousand people had to be evacuated, and over a thousand homes were just burned like that. I’m sorry that happened to them, but I don’t have a reaction to that like if this place burned and I had to evacuate.

You can see right there the favoritism towards “I” and how that grasping at a real “I” makes us suffer. Because the more we’re attached to something, the more we cling on to it as “mine,” then when something happens to it, we suffer. And something surely will happen to it because everything changes and nothing lasts forever. As long as we cling then when something happens we freak out. My thermos looks really permanent, and it’s strong. Look how strong it is! [laughter] But if something happens to MY thermos, and I am on a transoceanic flight without my thermos, there’s going to be a lot of suffering.

I’ll write everybody about how my thermos got lost before I got on the flight, and I had to do this whole flight drinking out of little paper cups—that they don’t even bring around when you’re thirsty! They bring them around when you’re asleep! [laughter] So, we can see how much that grasping narrows our perspective. We can barely see other people—only in terms of how they relate to me. And everything is how it relates to me.

There’s a whole huge, infinite universe with countless sentient beings, and I’m going through life blocking everything out except one tiny little spot in front of me. And, of course, when I’m blocking almost everything else out, and the one thing that I see right in front of me all the time is ME, I, MY and MINE, then I’m going to be quite miserable. And I’m going to create more causes to be reborn in samsara, and so here we are—2022—and still in samsara.

So, what we’re trying to do through the Vajrasattva practice is to learn to see what is reality. That was the big question in—what was that movie? It was some kind of musical or film when we were young with the big question of “What is reality?” Anybody remember what it was? I’m just trying to share another oldie but goodie with some of you. [laughter] I can’t remember the name of it. It was kind of like a musical.

Audience: Hair.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Hair! Yeah, Hair. You don’t know Hair? I think it was part of that, or it was the Meaning of Life—something like that.

How did we get off on that? [laughter] Oh yes, what is reality? That’s what we’re trying to see when we do the Vajrasattva practice, and what we’re trying to understand. And so, in order to see reality, we need to get rid of a lot of the obstacles that we have. One of the big obstacles we have is that whole compilation of negative karma that we’ve created. All of those first few links of the different sets of twelve links that we’ve accumulated—and all the other karma that’s not propelling karma that pushes us into a rebirth, but completing karma that determines or influences what we will experience in that rebirth.

We need to do some big purification about that, and of course, meditating on emptiness is the ultimate purification. Seeing reality is the ultimate purification. But before we can even do that, then there are these other methods to help us cleanse our mind and really get rid of a lot of the garbage. It’s kind of like our mind is like a garbage dump.

Have you ever been in a city in a developing country where there’s a garbage dump outside the town, and the garbage is just overflowing completely in a whole big area? Our mind is kind of like that. And when there’s a lot of garbage, you can’t see very clearly. It’s like when your glasses are dirty and you can’t see. So, the Vajrasattva practice is very much one of trying to cleanse a lot of this gross stuff away so that we can begin to see things clearly.

Vajrasattva is not judging us

Vajrasattva is our friend in helping us do this. And this is very important because especially people who came from a Judeo-Christian idea of God, if you make Vajrasattva into God, then what’s Vajrasattva going to be doing? He’s going to be outside looking at you, judging you. That’s because we’re imputing the Judeo-Christian concept of God onto Vajrasattva.

Vajrasattva is not sitting outside looking at us, judging us. Vajrasattva is an enlightened buddha. Do enlightened buddhas judge sentient beings? Is that a quality of enlightenment—that you judge other sentient beings and that you send them to hell or you send them to heaven? Is it a quality of enlightenment that you create suffering for them? Is any of that a quality of a buddha? Do you work enough for three countless great eons to become a buddha and then all you do is sit there and judge other people and send them to hell or heaven or create problems for them to test them? No. So, don’t put that on Vajrasattva.

Remember, Vajrasattva is on your side. He’s trying to help us. And he doesn’t judge. So, it can be kind of a new experience for us to try and open up and have a dialogue with somebody who is not going to judge us—somebody who we trust in that way. When we’ve been taking refuge in other living beings, we can’t always trust them not to judge. We can try to be open, but there are certain things we do not want to acknowledge, because if other people know them then they could use that against me. And that attitude keeps us tied up, doesn’t it?

It makes those things that we don’t want to admit more powerful because we have to put so much energy into concealing them. It ties up a lot of our energy. Whereas when we realize that those things are not inherently existent, we understand that we may have done egregious things, but they can be purified. And our having done those things does not make us a bad person. The action and the person are different. We can talk about what we’ve done or what we’ve experienced, and we acknowledge it, but at the same time, we know that we are not bad people. And we can purify those things. Plus, those things that we did, that we’re trying so desperately to stuff away and not admit to anybody, they are not happening now. So, why are we so afraid of them? They’re not happening now.

What’s happening is our memory. Is our memory the same as the actual action? No. A memory is just conceptual images in our mind, but that event is not happening now. So, we don’t need to be afraid of it, and we can open up and trust Vajrasattva and acknowledge whatever that was. Vajrasattva is on our side, and he’s going to help us to to let go of that. Whatever negativity is still hanging around from our previous action, or from something other people did with us as the object, all of that is getting cleansed away.

We don’t need to spend our time trying to sequester it so that nobody knows about it, because all the buddhas and bodhisattvas already know. We’re not keeping anything from them. The buddhas are omniscient, so why are we trying to keep something from them? That’s ridiculous. It can be quite a new experience for us to open up in that way, to have that level of transparency. But try it. Maybe you can’t open everything up instantly, completely, but do it little by little, little by little, and develop some confidence. And remember, Vajrasattva—when he’s on the crown of your head or if you visualize him in front of you—is looking at you with compassion. And you have to visualize him looking at you with compassion.

Some people may find that difficult because their first thought is: “If other people are really looking at me, they’re going to see how awful I am. They’re not going to look at me with compassion.” So, already our whole MO, our whole way of approaching other living beings, is with suspicion, because they’re going to judge me. “I’m not safe—not safe. They’re going to judge me. I can’t open up. They’ll use it against me.” All of that is coming from our own mind. It’s not coming from outside. Remember, Vajrasattva is sitting with the vajra and bell. He’s not sitting with his hand on his hip saying, “Tell me the truth: did you steal the bubble gum from your sister?”

We don’t need to hide like that. And when we were four years old stealing bubble gum from our sister, it may have been a big thing in the family because our parents were trying to teach us what the word “steal” meant because we didn’t understand it. When you’re a baby, you don’t understand the word “steal.” Everything is there and you want to touch it, and there’s no idea of ownership. Can you imagine not having an idea of ownership? And when you’re a baby, people are okay if you grab everything. They don’t say, “That’s mine!” It’s an interesting thing, isn’t it? And then we develop this idea of an “I” who is the owner of “mine,” and other people have this I, too, and they own things. And then the tug of war starts.

So, we can trust Vajrasattva and admit, “Okay, here’s the most awful thing I did.” But like I said, you don’t have to start with the most awful thing you did. You can start with stealing the bubble gum when you were five years old. Admit something simple and then work up to it. But I find it helpful to say, “Okay, here it is, and I’m not going to deny it. And I want to purify because I don’t want to do that again.”

Or I can ask for Vajrasattva’s help if something negative happened to me, and I don’t want to be involved in that situation because I don’t want to hate the people who did the something to me. I don’t want to go through my life hating people. I don’t want to go through my life fearing people. So, I’m asking for Vajrasattva’s help to wash away the anger, the hatred, the fear. And Vajrasattva is kind, and he helps us. He doesn’t say, “I’m getting off your head and going somewhere else! I’m not going to help you!” [laughter] And then Vajrasattva stands up and walks over to somebody else’s head and sits down. [laughter] That’s not going to happen.

This is quite a beautiful practice when we can ease ourselves into it. And things will come up. You can’t really keep everything hidden from a buddha because they already know it. So, when we try to hide stuff, we’re really keeping it from ourselves. And that just takes a whole lot of energy. So, we establish a relationship with Vajrasattva, and he becomes our best friend—a trusted friend, and a friend that always gives us good advice, not a friend who gives us bad advice.

He gives us good advice. And then when you’ve heard a lot of teachings and run into a problem and need some help, you do a quick mental call—911—up to Vajrasattva. He says, “Yeah, what do you need this time?” [laughter] No, he doesn’t say that. And we say, “Vajrasattva, my mind is going berserk, and I am overwhelmed by attachment. I am overwhelmed by spite. I am overwhelmed by dissatisfaction or loneliness or whatever it is—help me.” And when you’ve heard a lot of teachings, then something comes into your mind telling you, “This is what I need to practice right now.”

So, Vajrasattva is on the other end of the line, and he gives you good advice and then you practice it. And that’s very helpful because then whatever’s going on in your life, you have access to what is actually your own wisdom. We’re thinking of it as Vajrasattva’s wisdom because we’re very used to everything being outside of us. This is a way to get us to access our own wisdom, by thinking that Vajrasattva is giving us the teaching on what to practice.

It’s very helpful to do that. I usually find that when my mind is just unruly, I get very short and sweet advice in the form of: “Keep it simple, dear.” Because what am I doing when my mind is all confused and angry, or filled with desire, or dissatisfied? What am I doing? I’m elaborating on things, making things better than they are, making things worse than they are—projecting, elaborating, this mental factor of distorted conception or inappropriate attention. I’m just fabricating, and then getting all upset about what I fabricated.

Lama Yeshe would come out with these really pithy things, like “Keep it simple, dear.” Because he called everybody “dear.” So, now I think: “Oh yeah, keep it simple. Stop the proliferating mind. Stop telling myself lies”—lies like impermanent things are actually permanent; that things that are of the nature of duhka are actually going to bring me real pleasure; that things that are foul are in fact beautiful; and that things that lack a self have a self. That’s part of what I’m fabricating that then makes me afraid.

I fabricated and then projected on somebody. I overestimate the good qualities of somebody, and now they’re permanent, now they’re pleasurable, now they’re pure. There is a real self in them. I feel that I’ve got to make a relationship with that person. And then I suffer because they don’t look at me, or they look at me in the way I don’t want to be looked at, or they look at me a whole lot and I’m tired of it already. [laughter] Or they also look at other people, not just me. Or they look at me and tell me I’m fat and that I should look different than I look, that I should be different than I am. So, I suffer. I fabricate and then project it outward, bump up against whatever I’ve created someone—or an opportunity or a situation or an object—to be, and I’m not happy.

Those are some of the big elaborations we put out there, but then there are all the other ones. We are not simply thinking, “Oh, I’m seeing everything as permanent—yeah, yeah, yeah, what else is new?” We’re thinking, “This thermos is REALLY permanent, stable, and it is MINE forever. And it was given to me by my mother, so it’s SPECIAL. My mother’s love is permeating this purple—or pink or whatever color this is. It’s permeating this, so when I hold my thermos, I think of my mother.” Do you have things like that, where you think of somebody else that you love when you have that object? And then somebody on the plane runs over my thermos with that cart. [laughter] They run over it with the cart with the water that’s supposed to go IN the thermos, and the cart goes ON the thermos, and my thermos is shattered!

It’s important to look and see how we project. We create a reality that isn’t there and then react to it. Vajrasattva says, “Keep it simple, dear.” Or maybe Vajrasattva says, “Remember, it’s impermanent.” Or maybe Vajrasattva says, “It’s not just you in this universe.” [laughter] “Oh, God! I have to be reminded of that!” Oh yes, sometimes Vajrasattva needs to remind me that I’m not the only person in this universe. My parents told me that, too, but somehow I didn’t internalize it.

Take the time when you’re doing meditation to build up this relationship with Vajrasattva. People who are doing the Medicine Buddha retreat in the winter develop a similar kind of relationship with Medicine Buddha. And don’t think, “Well, Vajrasattva won’t judge me, but Medicine Buddha might. Medicine Buddha might look at me and say, ‘I told you to take your vitamins when you were little, and you didn’t listen, and now you’re sick.’” I don’t think Medicine Buddha is going to say that.

My left eye is very weak. When I was little they had a way to correct it. You know how they correct weak eyes? You wear a patch over your eye. That’s what they wanted me to do. I had no intention of looking like a pirate in grammar school. I refused to wear a patch over my eye, weak eye or not. I was not wearing a patch. And so, my whole life I have had a weak eye. Do you think Medicine Buddha is going to look at me and say, “Kiddo, I told you to wear that patch when you were little. Why didn’t you listen?” No, Medicine Buddha is more likely to say, “Now, I’ve been trying to lead this one to awakening for a long time, and she doesn’t do even the simplest thing I tell her to do that would be beneficial for her, BUT I’m still going to keep trying. I’m not going to give up.”

The buddhas and bodhisattvas keep trying to help us, and we keep saying, “No, I’m not going to wear the patch on my eye. No, I’m not going to give up what I want! No, I’m not going to do what I don’t want to do!” And we think, “I can’t stand when other people don’t do what they’re supposed to do! I’m not going to give up being mad at them because they’re not doing what they’re supposed to do—even if they don’t know what they’re supposed to do. But they should know what they’re supposed to do, and they’re not doing it. And I can’t control them!”

They are the buddhas. They don’t give up on us. They don’t say, “Ciao, Kiddo, I’ve been trying for countless eons to help you, and I’m fed up already.” And then they walk out. They don’t do that. They keep trying, so we have to keep trying. Now that we have this kind of rebirth—it’s a kind of special rebirth—so we have to keep trying to open up, to connect with them. Because when you’re born as a kitty cat, or a flea, or a gopher, or an anteater, or a kangaroo, or a hell being, or a preta, or spaced out in the formless absorption realms, you can’t create that kind of relationship. So, this is our chance.

Questions & Answers

Audience: Can a person do Vajrasattva practice without any tantric initiations?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yes, you just keep Vajrasattva either in front of you or on your head, and at the end, he melts into light and dissolves into you and kind of settles at your heart. But you don’t visualize yourself as Vajrasattva.

Audience: In the meditation, we purify our body, speech, and mind, imagining Vajrasattva is in us instead of purifying our body with our own powers. Is this because we are not able to acknowledge our weakness?

VTC: When we’re doing the practice, Vajrasattva is above our head—or in some sadhanas he’s in front of us—and we imagine the blissful wisdom nectar, which is the nature of compassion, flowing into us. When we say that we’re purifying our body, it means that we are purifying the karmic imprints—the karmic seeds of negative actions that we’ve done physically with our body. That’s what it means. When you’re sick, you can also imagine the light and nectar from Vajrasattva going to the area where you are ill, or if there is pain, the light and nectar goes there and you can imagine it healing that area.

Audience: Regarding selflessness, once we open ourselves up, we become less attached to ourselves. Does letting go then become easier through this practice? Is this how this practice helps us to practice emptiness as well?

VTC: Yes, yes, and yes! [laughter] You’ve got it.

Audience: The way I understand the practice works is that by repeatedly engaging the practice with close attention, it brings a more embodied understanding of the three principal aspects of the path. Is this so?

VTC: Doing the purification removes obstacles to our understanding of the three principal aspects of the path, but to develop those understandings in our own mind we have to meditate on them. They’re not going to appear magically, so we have to do the meditations to generate the determination to be free. We have to do the whole series of meditations to generate bodhicitta and apply the reasonings to realize emptiness. It’s not just purification.

Audience: What is the difference between healing and purifying?

VTC: They probably come to kind of the same thing, just depending how you look at it. Vajrasattva would emphasize the purifying aspect. Medicine Buddha would emphasize the healing aspect. But when you really plumb both of them, they kind of come to the same point.

There was also a question from yesterday about whether the Vajrasattva prostrations are another version of the Vajrasattva practice, or if they are another option, or if that is a different level of practice. Usually, when we’re doing the Vajrasattva meditation—especially if you’re doing it as a preliminary practice and counting the mantra—we do it seated, and Vajrasattva is on our head, and we do the recitation that way. But it’s also very nice during the break times or even when you’re not in a retreat situation, if you want to do prostrations, you can visualize Vajrasattva, prostrate, and say the mantra when you’re prostrating.

Audience: Sometimes I feel like I have less of a fear of being judged but more of a fear of the recognition that I’m going to be here for a lot longer in cyclic existence. Is there a way to recognize my own faults without getting so caught up in the consequence of the karma and being stuck in samsara itself.

VTC: When we meditate on karma and so on, and we see the disadvantages of destructive karma, the purpose is to invigorate us so we want to be free of samsara. If you’re meditating on that and then just thinking, “I’m afraid of being in samsara for a long time,” and you get stuck just with being afraid, then you haven’t gotten to the conclusion that Vajrasattva wants you to get to. The conclusion is, “If I don’t practice, I will be in samsara a long time, but now I’ve found the method to practice. I want to get out of samsara, so now I’m going to put my energy— joyfully, enthusiastically, willingly, and voluntarily—to create the causes for liberation.” Because just sitting and thinking, “I’m going to be in samsara for a long time,” what does that get you? “I’m going to be in samsara a long time. I’m going to be in samsara a long time”—that’s your new mantra—”I’m going to be in samsara a long time.” If you think like that, you will be in samsara a long time, but that’s not the conclusion that Je Rinpoche wanted when he wrote The Three Principal Aspects of the Path. It was for us to develop our courage and our enthusiasm to really engage in the practice, so we won’t be in samsara for a long time.

Audience: Do we purify ourselves depending on our own powers and abilities ultimately? Can you elaborate on this?

VTC: They say that it’s kind of like a joint effort—one of those projects that is a joint effort between Vajrasattva and you. There are holy beings, and they do wish us well and they do try and help us. But the amount of help that we can receive from them is dependent on the amount that we’re open, so we have to help ourselves open, help ourselves purify. At the same time, the buddhas and bodhisattvas are trying to help, but Buddhism does not work if we think, “I’m hopeless. I can’t do anything, so I’m just going to pray to Vajrasattva and let him take care of it.” No, Buddhism very much requires our effort: “I’ve got to be responsible for my own welfare and for the welfare of others.”

Audience: Why do we change between different deities in winter retreat from year to year? Isn’t it better to keep to one?

VTC: What we do here at the Abbey is we change the deity from year to year because we’re reaching out to the public, and there may be different people that prefer one deity more than another. But in terms of your own practice, if there’s one deity that you feel an especially strong connection with, do that practice every day. Don’t just do a long retreat and then think, “Okay! I did my 100,000 Vajrasattva—been there done that, got the t-shirt. I never have to recite that mantra again! Forget about Vajrasattva. Now Medicine Buddha’s going to be my favorite.” And then you meditate on Medicine Buddha for one month or two years or whatever it is, and think, “Okay, I’ve recited the mantra for that—been there, done that. Bye, Medicine Buddha. I’m done with you; I’m on to the next one.”

You know these people who have serial partners? [laughter] You fall in love with one person, you break up with them, and the next day you’re in love with somebody else—it’s not like that. If you want to develop a relationship with a buddha, you don’t treat them like that. You do the retreat, and after the retreat, you don’t just stop the practice cold and go on to another one. You do maybe a modified, abbreviated version of the practice, or if you really resonate with that deity, you continue using that one as your main practice. And so, maybe Vajrasattva’s your main practice, so you do that every day, but then it’s fine to do Medicine Buddha retreat, too. You still do a short Vajrasattva practice while you’re doing your Medicine Buddha retreat.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.