Teaching in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union

Part 1

- Vividness of war in the Eastern Europe

- Economic difficulties following the fall of communism

- Psychological loss in former Soviet Union countries

- Problems in adapting Buddhism philosophy

- Looking into the negative effect of the fall of communism

- Poverty in Romania

- Ethnic hatred in Transylvania

Travels in Eastern Europe 01 (download)

Part 2

- A sectarian approach to Buddhism

- Underground spiritual practice

- Meeting Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo in Krakow

- The need to adjust monastic vows to modern times and circumstances

Travels in Eastern Europe 02 (download)

Part 3

- Remnants of infrastructure of the holocaust

- The disintegration of the Jewish section of Auschwitz

- Hardships endured by the occupied countries during the war

- Different versions of history

- Visiting monument of the Warsaw uprising

- Disorganization of the former Soviet Union

- A controversial lama

- Comparing Chinese Communism in Tibet with the situation in Russia and Lithuania

- How Tibetan Buddhism is viewed in former Soviet Union

Travels in Eastern Europe 03 (download)

Note: The text below is a separate write-up about the same trip. It is not a transcript of the above audio talks.

Planning for the trip to Eastern Europe and former Soviet Union (FSU) was an adventure in itself, with my passport getting lost twice in the U.S. mail, the Ukrainian embassy refusing my visa, and the travel agent keeping my urgent itinerary at the bottom of the stack of papers. I called the places in Eastern Europe to let them know the dates of my visit, and a man in St. Petersburg was supposed to organize the part of the tour in FSU. But I soon learned that organizing a 16-city teaching tour in former communist countries made travel in India look like a piece of cake.

My first stop in Eastern Europe was Prague, a beautiful capital whose buildings were comparatively unscathed during World War II. I stayed with Marushka, a delightful woman with whom I’d been corresponding for a number of years, although we had never met. She had been hospitalized twice for emotional difficulties and told me hair-raising tales of being in a communist mental institution. Juri, my other host, showed me around the city, one memorial site being the exhibit of children’s art in the Jewish museum. These children, confined in a ghetto in Czechoslovakia during the war, drew pictures of the barbed wire compounds in which they lived and the cheerful houses surrounded by flowers in which they formerly lived. Below each drawing were the child’s birth and death dates. Many of these little ones were taken to Auschwitz to be exterminated in 1944. All over Eastern Europe and the FSU, the ghost of the war reigns. I was constantly reminded that the demographics of the area changed radically in a few years and that people of all ethnic groups suffered.

My talks in the Prague were held downtown. They were attended by about 25 people, who listened attentively and asked good questions. Jiri was an able translator.

The next stop was Budapest, where spring was just beginning. Most of the city had been destroyed by door-to-door fighting at the end of the war. I stayed with a lovely extended family, two members of whom had escaped during the communist regime and gone to Sweden to live. The talks were at the recently-established Buddhist College, a first in that part of the world. But I was surprised when entering the principal’s office, to see on the wall behind his desk not a picture of the Buddha, but a painting of a nude woman!

I also visited a Buddhist retreat center in the countryside where ten people had just begun a three-year retreat. Over lunch, the Hungarian monk explained the difficulties that people raised under communism have when becoming Buddhists. “You don’t know what it’s like to learn Marxist-Leninist scientific materialism since you’re a child. This does something to your way of thinking, making it a challenge to expand your mind to include Buddhist ideas,” he said. True, I thought, and on the other hand, people in Western Europe and North America have to undo years of indoctrination of consumerism and if-it-feels-good-do-it philosophy when they encounter Buddhism.

Oradea, a town in Transylvania (Rumania) that is renowned as Count Dracula’s home, was the next stop. Rumania was much poorer than Czech Republic and Hungary, or rather, it was more neglected. As I later found in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, people had things, but they were falling apart and left unrepaired. The roads, once paved, were now rutted. The trams, once brightly painted, were now dilapidated. There was no idea of fixing things, or if there was, no money to do it. Transylvania was traditionally inhabited by Hungarians and in recent years, there has been an influx of Rumanians. The Dharma group was mostly Hungarians and took every opportunity to tell me how awful the Rumanians were. I was shocked at the prejudice and ethnic hatred, and found myself talking passionately about equanimity, tolerance, and compassion in the Dharma talks.

The people I stayed with were kind and hospitable, and as in most places, I felt real friendships develop. However, they knew little about etiquette around monastics, and at a gathering in someone’s flat after a talk, I was surrounded by couples making out. They would take turns talking to me and then resume their (obviously more pleasurable) activities. Needless to say, I excused myself as soon as possible and went to my room to meditate.

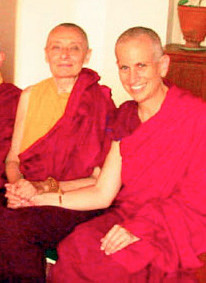

With Venerable Tenzin Palmo.

Then on to Krakow, Poland, the site of Schindler’s List. Venerable Tenzin Palmo, a British nun who meditated 12 years in a cave in India, was also teaching in Poland at the time, and our schedules were arranged so we could meet in Krakow. It was lovely to see her again, and together we discussed the recent tragedy that had befallen many Polish Dharma centers. Years ago, a Danish teacher in the Tibetan tradition had set up centers in many cities. But in recent years power struggles developed, and the teacher, becoming involved in the Tibetans’ dispute over the new Karmapa, forbade his centers to invite other teachers from even his own Tibetan tradition. As a result, the centers throughout Poland split into opposing groups, with the Danish man and his followers retaining the property. The tragedy is that many friendships have disintegrated and much confusion generated about the meaning of refuge and relying on a spiritual mentor. Venerable Tenzin Palmo and I did our best to alleviate the confusion, encouraging people in the new groups to go ahead with their practice, to invite qualified teachers, and to practice together with their Dharma friends. This experience intensified my feeling that we Westerners need not and should not get involved in political disputes within the Tibetan community. We must remain firmly centered with a compassionate motivation on the real purpose of Dharma practice and check teachers’ qualifications well before establishing a teacher-student relationship with them.

The Poles were warm and friendly, and we had long, interesting and open talks. “As an American, do you have any idea what it’s like to have your country occupied by foreign forces? Can you imagine what it feels like to have your country carved up and your borders rearranged at the discretion of powerful neighbors? Do you know how it feels when citizens are deported to foreign lands?” they asked. All over Eastern Europe, people remarked that their countries were the walking grounds of foreign troops, and indeed so many of the places were alternately occupied by the Germans and the Russians. The smell of history lingers on in each place.

Inter-religious connections

I enjoy inter-religious dialogue and while in Prague met with the novice training master at a monastery. In Budapest, I met with a monk from a monastery with its church carved as a cave in the rock along the river in Budapest. In both these conversations, the monks were open and curious about Buddhism—I was probably the first Buddhist they had met—and they shared their experiences of following their faith despite the fact that their monasteries had been shut down during the communist regime.

In Krakow, Venerable Tenzin Palmo and I visited some sisters of St. Francis at their cloister in the center of the city. Two sisters in full traditional nuns’ dress sat behind the double grill as we exchanged questions and answers about spiritual life and practice. One topic of interest was how to keep our religious traditions alive and yet adapt to the circumstances of modern life, challenges that both Buddhist and Catholic monastics face. Our discussion lasted two hours, and by the end 13 Catholic nuns (half of the monastery’s inhabitants) were crammed into the tiny room. With much laughter we showed them how our robes were worn and they peeled off layers of black and white cloth to show us how to assemble their robes. We traded prayer beads through the grill, like teenage girls sharing secrets, and parted with a sense of love, understanding and shared goals.

Later, in Russia and Ukraine, I tried to meet with Orthodox nuns, but could not find any. One large Orthodox nunnery we visited in Moscow is now a museum. Fortunately, in Donetsk, Ukraine, a young Orthodox priest and a Catholic woman attended my talk at the Buddhist center. We spent a long time talking about doctrine, practice, and religious institutions. I explained to the priest that many people in America who had been raised Christian suffered from guilt. From their youth, they were told that Jesus had sacrificed his life for them and they felt they were too egotistical to appreciate or repay this and asked how this could be alleviated. He explained that many people misunderstand Jesus’ death—that Jesus sacrificed his life willingly, without asking for anything in return. He also said that women played a greater role in the early Church than they do now in Orthodoxy, and that slowly, he would like to see them resume that place.

Venerable Tenzin Palmo and I also visited Auschwitz as well as the Jewish neighborhood, the ghetto, and the cemetery in Krakow. It was rainy and cold those days, the weather illustrating the horror of what human beings’ destructive emotions can perpetrate. Coming from a Jewish background, I had been raised knowing about the tragedy there. But I found it odd, and all too familiar, that people were now vying for their share of suffering and pity. Some Jews objected to a Catholic nunnery being built near the concentration camp, and some Poles felt that the fact they lost a million Polish patriots at Auschwitz wasn’t adequately recognized by the world. The importance of meditating on equanimity became obvious to me—everyone equally wants to be happy and to avoid suffering. Creating too strong of a religious, racial, national, or ethnic identity obscures this basic human fact.

In Warsaw, I went to the site of the Jewish Ghetto where now a monument stands for those who died in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. The area is a park surrounded by socialist flats, but old photos reveal that after the uprising it was nothing more than leveled rubble. At the Jewish cemetery, we overheard an older woman visiting from America say that she had been in Warsaw at the time of the uprising and came back to look for the graves of her friends. It seems to me that Caucasians haven’t completely come to terms with the atrocities committed under Hitler and Stalin (to name a few)—they view these as flukes or aberrations, because white people could never cause such heinous events. I believe that this is why we have such difficulty grappling with events such as the situations in Bosnia and Kosovo in the 1990s.

From time to time on the trip, I met some Jewish Buddhists, in Eastern Europe and the FSU, where so few Jews are left! They are generally assimilated into the main society now, and although they say, “I am Jewish,” they don’t know much about the religion or culture. It’s similar to many people from my generation of Jews in USA. In Ukraine they told me that since so many Russian Jews in Israel can get Ukrainian TV, that there are now advertisements in Hebrew on their TV! They also told me that since things opened up in the FSU, that many of their Jews friends have left for Israel and the USA. It was interesting that the people I met didn’t want to leave, given how chaotic and directionless those societies are now.

The transition from Communism to ??

As I traveled northward, spring disappeared, and I entered the countries of the former Soviet Union, where winter lingered on. I realized that the person in St. Petersburg who was supposed to organize this part of the tour had dropped the ball. Some places didn’t know I was coming until I called them the night before to give them the arrival time of the train! People told me this was normal—since the disintegration of the Soviet Union, ties had been broken, there were now border checks and customs in what used to be one country, and things were not well organized.

All over Eastern Europe and the FSU, people told me how difficult the change from communism to free-market economy and political freedom had been. First there were economic hardships due to the changing system. Then there was the change in mentality required to cope with it. People said that under communism they lived better—they had what they needed—while now they had to struggle financially. Under the old system, things were taken care of for them, and they didn’t have to take personal initiative or be responsible for their livelihood. They worked a few hours each day, drank tea, and chanted with their colleagues the rest, and collected a paycheck that allowed them to live comfortably.

Now, they had to work hard. Factories were closing down, and people losing their jobs. Although the markets had plenty of Western goods, in the FSU hardly anyone could afford them. Even people who were employed were not paid well, if their employers had money to pay them at all. Many educated and intelligent people, especially in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine left their jobs to do business, buying and selling from one place to another. The poverty was real. In the Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine we basically ate rice, bread and potatoes.

In Eastern Europe, the situation was not so grave, and the mood was upbeat. People were glad to be free from communism and from Russian domination. Circumstances were difficult, but they were confident they would get through them. The people in the Baltics felt the same and were especially happy to have their independence. In all these areas, which had been under communism only since the war, the people removed the statues and symbols of communism as quickly as possible.

But in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine, areas that were communist since the early 1920s, the atmosphere was different. Economically, they were more desperate, and socially, more disorganized. Their great empire was lost and their confidence destroyed. Only one woman I met in Moscow saw the present situation optimistically, saying that Russians now had the opportunity to develop an economic system which was neither capitalist nor communist, a system which could fit their unique cultural mentality.

But others I met felt confused. With the advent of perestroyka, things snowballed, changing so fast in ways that no one had expected, with no advance planning or firm direction for the society. Now clever people are profiteering from the chaos, and the gap between rich and poor is growing. It broke my heart to see old grandfathers in St. Petersburg begging outside the churches and old grandmothers in Moscow with their palms held out in the subways. Such things never happened before, I was told. But when I asked people if they wanted to return to the old system, they replied, “We know we can’t go back.” Yet, they had little idea of what lay ahead, and most did not have confidence in Yeltsin’s leadership.

The Baltic countries and the former Soviet Union

Back to my time in the Baltics. I taught in Vilnus (Lithuania) and Riga (Latvia), but had the best connection with the people in Tallinn (Estonia). They were enthusiastic, and we did a marathon session on the gradual path to enlightenment, after which all of us were elated and inspired.

In previous decades a few people from the Baltics and St. Petersburg had learned Buddhism, either by going to India or to Buryatia, an ethnically Buddhist area in Russia just north of Mongolia. Some of these people were practitioners, others were scholars. Yet, the public has many misunderstanding about Buddhism. I was asked if I could see auras, if Tibetan monks could fly through the sky, if one could go to Shambala, or if I could perform miracles. I told them that the best miracle was to have impartial love and compassion for all beings, but that wasn’t what they wanted to hear!

I met people who had learned a little about tantra from someone who knew someone who knew someone who had gone to Tibet in the twenties. Then they read Evans-Wentz’s book on the six yogas of Naropa, invented their own tummo (inner heat) meditation and taught it to others. They were very proud that they didn’t have to wear overcoats in the icy Russian winter, while I was relieved that they didn’t go crazy from inventing their own meditation. It brought home to me the importance of meeting pure lineages and qualified teachers, and then following their instructions properly after doing the necessary preliminary practices.

The teachings in St. Petersburg were well attended. While there, I visited the Kalachakra Temple, a Tibetan temple completed in 1915 under the auspices of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. In the 1930s, Stalin had the monks killed, and the state took over the temple, turning it into an insect laboratory. In recent years the Buddhists were allowed to return, and there is now a group of young men from Buryatia and Kalmykia (between the Caspian and Black Seas) who are training to be monks. The women at the temple, some European, others Asian, were enthusiastic about Dharma, and we talked for hours. With excitement, they kept saying, “You’re the first Tibetan nun who’s been here. We’re so happy!”

In Moscow, the teachings were organized by a new-age center, although there are many Buddhist groups in the city. Before leaving Seattle, I met with the Russian consul, who was interested in Dharma. He gave me the contact of his friend in Moscow who was a Buddhist. I looked him up and had an impromptu meeting with some of the people from his group. We discussed Buddhism from the point of view of practice not theory, and there was a wonderful and warm feeling at the end of the evening.

Then on to Minsk, Belarus, where the trees were barely beginning to bud and the Dharma group was earnest. Again, people were not very familiar with etiquette for monastics, and I was housed at the flat of a single man who had a huge photo of a naked woman in his bathroom. Fortunately, he was kind and minded his manners, but it put me in an awkward position—do I ask to stay elsewhere even though everyone else’s flats were crowded?

On the way from Minsk to Donetsk, we stopped for a few hours in Kiev and met a friend of Igor, the man translating for me. She and I had a good connection and I was touched by how she shared the little she had with us. She and I were about the same size, and the idea popped into my head to give her the maroon cashmere sweater that friends had given to me. My ego tried to quench that idea with all sorts of “reasons” about my needing it. A civil war broke out inside me on the way to the train station, “Should I give her the sweater or not?” and I hesitated even after she got us sweet bread for the trip, although she had little money. Fortunately, my good sense won out, and I reached into my suitcase and gave her the beautiful sweater minutes before the train pulled away. Her face lighted up with delight, and I wondered how I could have considered, just five minutes prior, being so stingy as to keep it myself.

Donetsk, a coal mining town in eastern Ukraine, was the last stop. Here I stayed at a center begun by a Korean monk, where the people were friendly and open to the Dharma. The town had little “Mount Fujis” all around it. When the mines were dug, the excess earth was piled in hills of pollution around the town. Nevertheless, the town had trees and green grass—welcome sights after the dreariness of Moscow—and spring was again present. In addition to speaking at the center, the public library, and a college, I gave talks to two large groups at a high school, with many students staying afterwards to ask more questions.

With a good sense of timing, after finishing the last talk of this six-week tour, I promptly lost my voice. On the train from Donetsk to Kiev, I was coughing and sneezing, and the compassionate people who shared the train compartment, two slightly tipsy Ukrainian men, offered to share their precious vodka with me, saying that it would definitely make me feel better. But being unappreciative of their generosity, and using the (in their eyes) lame excuse that drinking was counter to my monastic vows, I refused. In an effort to overcome my ignorance, they kept repeating their offer, until I finally feigned going to sleep to have some peace.

As a final touch to the trip, on the flight from Kiev to Frankfurt, I sat next to an evangelical Christian from Seattle who had just been to Kazakhstan, Moscow, and Kiev to spread the “good news.” He was a pleasant man, who meant well and wanted to help others. But when I asked him if the Muslims who converted to Christianity faced difficulties with their families, he said, “Yes, but it’s better than going to hell.”

By the time I arrived in Frankfurt and my friend, a German monk, picked me up at the airport, I felt like Alice reemerging from the hole, wondering about confusing and wonderful experiences, the kindness and the complexity, that others had just shared with me.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.