A pilgrimage to Tibet

Many people have asked about my pilgrimage to Tibet this summer, but while one person wants to hear a travelogue, another is interested in the social and political situation, another in the Dharma, another in the mountains. So where do I begin? How about with the taxi ride from Kathmandu to the Nepal-Tibet border? The taxi broke down about 30 kilometers from the border—the fan belt was shredded. When the driver took out a piece of yellow plastic cord and knotted it together in an attempt to make a new fan belt, we decided not to wait for him and to hitch a ride to the border. That we did, and lo and behold, the taxi pulled up 15 minutes later!

Due to landslides, the road up the mountain from the Nepali border to just beyond Kasa, the Tibetan border town, was impassable. We trudged up the steep trails and mounds of rocks to the Chinese immigration office. From that moment on, it was clear that we were in an occupied country. The baggy green Chinese army uniforms don’t fit in. The Tibetans certainly don’t want foreign troops occupying their country as the Red Chinese have done since 1950. Judging by the attitude of the numerous Chinese I came in contact with there, they don’t seem too happy living there. They came to Tibet either because the Beijing government told them to, or because the government will give them better salaries if they go to colonize the more geographically inhospitable areas. Generally, the Chinese in Tibet aren’t very cooperative or pleasant to deal with. They are condescending towards the Tibetans, and following government policy, they charge the foreigners much more than locals for hotel accommodation, transportation, etc. Still, I couldn’t help have compassion for them, for they, just as we all are, are bound by previously created actions.

But to return to the travelogue—the next day we caught a bus ascending up to the Tibetan plateau. The bus ride was bumpy, with a mountain on one side of the road and a cliff on the other. Passing a vehicle coming from the other direction was a breath-taking experience (thank goodness, it wasn’t life-taking!). We ascended to the Tibetan plateau, headed for Shigatse. What a change from the lush greenery of lower altitudes! It was barren, with much open space and beautiful snow-capped Himalayan peaks. But what do the animals (let alone the people) eat? It is the end of May, but hardly anything is growing!

The bus stopped for the night at a Chinese military-operated truck stop near Tingri. It was an unfriendly place, but I was already feeling sick from the altitude and didn’t pay much attention to the controversies the other travelers had with the officials. I slept the next day on the bus, and by the time we arrived in Shigatse, felt okay. At first it is strange to be out of breath after climbing one flight of stairs, but soon the body adapts.

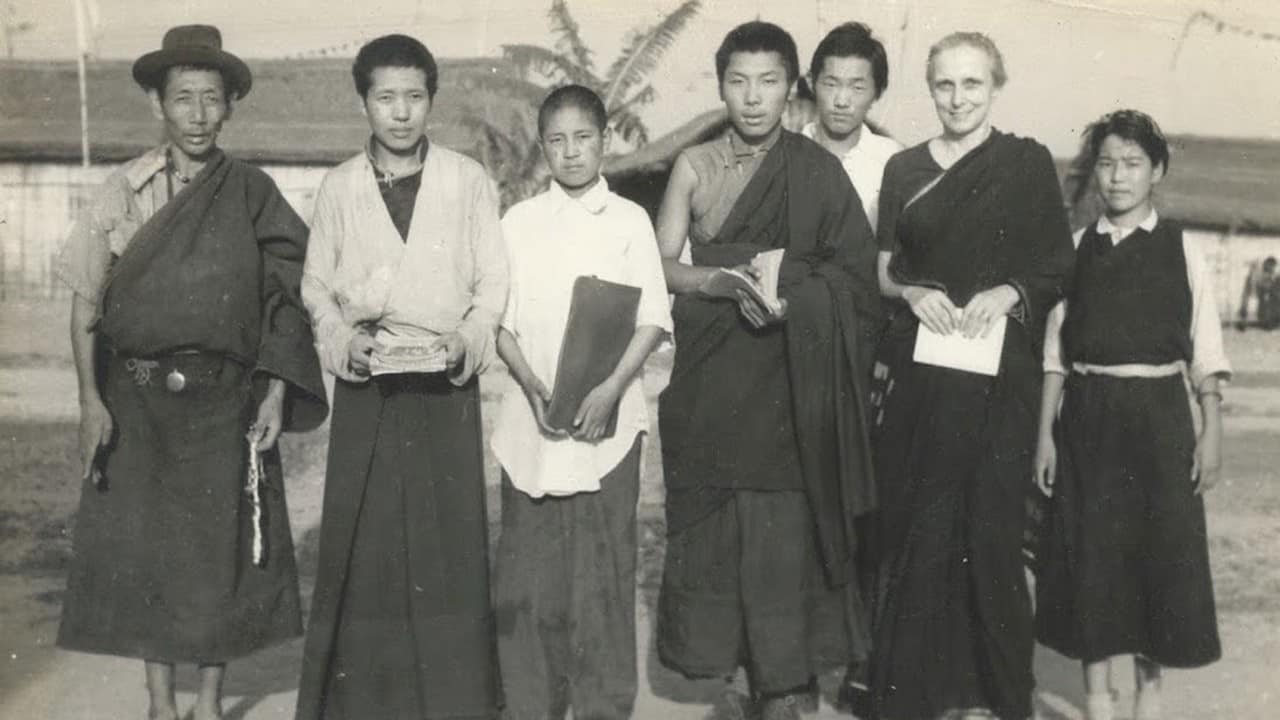

Tibetans’ warm welcome of Western monastics

Walking down the streets in Shigatse was quite an experience. People looked at me, some with surprise, most with happiness, for they are overjoyed to see monks and nuns after so many years of religious persecution in Tibet. Generally, the people know very little about other countries and peoples (some had never heard of America), so the sight of Caucasians is new. But a Western nun was almost beyond belief to them. As a young Tibetan woman later explained to me, the Chinese communists have been telling the Tibetans for years that Buddhism is a backward, demon-worshipping religion that impedes scientific and technological progress. Since Tibet has to modernize, the communists were going to liberate them from the effects of their primitive beliefs. This they did very efficiently by destroying almost every monastery, hermitage, temple, and meditation cave in the country, and by making the Tibetans lose the feeling of the dignity and value of their religion in a modern world. Although internally, most Tibetans never abandoned their faith and desire to practice the Dharma, the communist society around them makes that difficult. Thus when they see Westerners—who are educated in modern ways and come from a technological society—practicing the Dharma, they know that what they have been told during the Cultural Revolution was wrong.

Many people came up to ask for blessed pills and protection cords as well as for hand blessings. At first this was rather embarrassing, for I am far from being a high lama capable of giving blessings. But I soon realized that their faith had nothing to do with me. It was due to my monastic robes, which reminded them of His Holiness the Dalai Lama and their teachers in exile. Thus seeing anyone in robes made them happy. The closest many Tibetans can get to contacting His Holiness in this life is seeing Buddhist robes. Although they desperately wish to see His Holiness—I often had to choke back tears when they told me how they longed to see him—His Holiness cannot return to his own country now, and it is very difficult for the Tibetans to get permission to visit India. It began to dawn on me that my pilgrimage to Tibet was not just for me to receive inspiration from the many blessed places where past great masters, meditators, and practitioners lived, but also to act as a sort of link between His Holiness and the Tibetans. Again, this had nothing to do with me, it was the power of the robes and of whatever encouraging words I could say in garbled Tibetan.

Many people would give the “thumbs up” sign and say “very good, very good,” when they saw an ordained Westerner. This appreciation for the Sangha reminded me of how much we, who live in places with religious freedom, take that freedom for granted. We can easily go to listen to His Holiness teach; we can study and practice together without fear. Do we appreciate this? Do the Tibetans in exile appreciate this? As much as those in exile have gone through difficulties in the past, now they enjoy religious freedom and are far better off materially than those who remained in Tibet. It saddens me to recall Tibetan families in India who go to teachings with a thermos of butter tea and bread, and then chat and enjoy a picnic while His Holiness teaches.

One woman in Shigatse told me of the plight of her family after 1959. Her father and husband were imprisoned and all the family’s property confiscated. Living in poverty for years, she was sustained by her devotion to His Holiness during those difficult times. I told her that His Holiness always has the Tibetan people in his heart and constantly makes prayers for them and actively works for their welfare. Upon hearing this, she started to cry, and my eyes, too, filled with tears. Little did I know, after being in Tibet only two days, how many times during my three-month pilgrimage people would tell me even more woeful stories of their suffering at the hands of the communist Chinese government, and of their faith in the Dharma and in His Holiness.

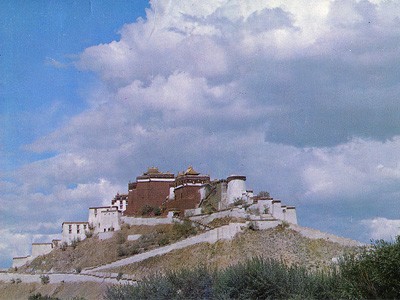

Potala Palace (Photo by Paul)

Then we went on to Lhasa, to meet Kyabje Lama Zopa Rinpoche and a group of approximately 60 Westerners doing pilgrimage with him. Like pilgrims of old, I strained to catch the first glimpse of the Potala and was elated when it came into view. Such a strong feeling of His Holiness’s presence arose, and I thought, “Whatever else happens during this pilgrimage, no matter what difficulties may arise, compassion is all that is important.” Several days later, when about 35 of us Westerners were doing the puja of the Buddha of Great Compassion at the Potala (to the amazed gazes of Tibetans, Chinese and Western tourists), this same feeling arose again. Compassion cannot be destroyed, no matter how confused and evil people’s minds become. There we were, Buddhists coming from a variety of countries thousands of kilometers away to meditate on compassion in a land that has endured incredible suffering, destruction, violation of human rights, and religious persecution since 1959. But anger at this injustice is inappropriate. It was as if people had gone crazy—what happened during the Cultural Revolution is almost too bizarre for comprehension. We can only feel compassion, and humility, for who amongst us can say with certainty that, given the conditions, we would not inflict harm upon others?

Early in the morning of the day celebrating the Buddha’s enlightenment, Zopa Rinpoche led a large group of Western Dharma students in taking the eight Mahayana precepts at the Jokang, Lhasa’s holiest temple. The crowd of Tibetans gathered around us were surprised, yet joyful to see this. As the days went on, we visited the Potala, Sera, Ganden, and Drepung Monasiteries, Ta Yerpa, Pabongka Rinpoche’s cave, and many more sights in the Lhasa area. Suddenly all the stories about great masters that I had heard for years became alive. I could envision Atisha teaching on the sun-drenched hillside of Ta Yerpa, and felt the peace of the retreat house above Sera where Lama Tsongkhapa composed texts on emptiness. In so many places figures of Buddhas have naturally arisen out of stone. At times, the stories of miracles, footprints in rocks, and self-emanating figures were a little too much for my scientifically educated mind, but seeing some of these broke some of my preconceptions. To tell the truth, some of the statues had so much life-energy that I could imagine them talking!

Destruction of Tibetan society and lack of religious freedom

My mind alternated between the joy of the inspiration of these sites, and the sadness of seeing them in ruins. Ganden Monastery was the hardest hit of the major monasteries in the Lhasa area, and it lies almost entirely in ruins. It is located at the top of a huge mountain, and as our bus laboriously chugged up there, I marveled at the perseverance of the Red Chinese (and the confused Tibetans who cooperated with them) in leveling the monastery. Especially years ago when the road was not so good (not that it’s great now), they really had to exert effort to get up the mountain, tear down a building made of heavy stones, and cart away the precious religious and artistic treasures. If I had a fraction of the enthusiasm and willingness to overcome difficulties that they had in destroying Ganden, and used it to practice Dharma, I’d be doing well!

In the last few years, the government has allowed some monasteries to be rebuilt. Living amongst the rubble of Ganden are 200 monks, who are now endeavoring to restore not only the building, but also the level of study and practice that once existed at this famous place, which is the site of Lama Tsongkhapa’s throne. Of those 200 only 50 are studying, the rest have to work or to help the tourists. The situation is similar in other monasteries. I also noticed that in most monasteries, the number of monks that were quoted exceeded the number of seats in the prayer hall. Why? I was told because they had to go outside to work or were at private homes doing puja. They must have stayed away for a long time, because I did not see them return although I stayed in the area a few days. When I inquired at the monasteries what texts they were studying, those few monasteries that had been able to reinstate the philosophical studies were doing the elementary texts. They had been able to start the study program only recently.

In spite of the recent liberalization of government policy, there is no religious freedom. Lay officials are ultimately in charge of the monasteries, and they determine, among other things, who can be ordained, how many monks or nuns a monastery can have, what building and work are to be done. In a few places I had occasion to observe that the rapport between the monks and the local officials in charge of the monastery was not relaxed. The monks seemed afraid and wary of the officials, and the officials at times were bossy and disrespectful to the monks and nuns. When I saw Tibetan officials like this, it saddened me, for it shows the lack of unity amongst the Tibetans.

After 1959, and especially during the Cultural Revolution, the Red Chinese tried to suppress the Dharma and harm Tibetans by violent means. Some people call it attempted genocide. But the effects of the recent, more liberalized policy is even more insidious. Now the government offers jobs to young Tibetans, although their educational possibilities and job positions are inevitably lower than those of the Chinese. In order to get a good salary and good housing, Tibetans have to work for the government. Some get jobs in Chinese compounds, where they then abandon Tibetan dress and speak Chinese. So slowly, in the towns, young people are leaving aside their Tibetan culture and heritage. In addition, this diluting of Tibetan culture is encouraged by the government sending more and more Chinese to live in Tibetan towns.

The fact that some Tibetans have government positions of minor authority divides the Tibetans in general. Those not working for the government say that government employees are concerned just with their own benefit, seeking money or power by cooperating with the Red Chinese. In addition, because they don’t know when the government may reverse its policy and begin gross persecution of Tibetans again, the Tibetans who don’t work for the government cease to trust those who do. They start to worry about who may be a spy. The suspicion that one Tibetan has for another is one of the most destructive forces, psychologically and socially.

The future of Buddhism in Tibet faces many obstacles. In addition to the mass destruction of the monasteries and texts that occurred in the past, the monasteries are now controlled by the government, and since l959 the children have had no religious instruction in school. Save for what they learn at home, people aged 30 and younger have little understanding of Buddhist principles. Many people go to temples and monasteries to make offerings and pay their respects, yet among the young people especially, much of this is done without understanding. Without public Dharma instruction available, their devotion will become more and more based on undiscriminating faith rather than on understanding. Also, monks aged 30 to 55 are rare, for they were children during the time of the Cultural Revolution. After the remaining teachers, who are already quite old, pass away, who will there be to teach? The young monastics will not have learned enough by then, and the generation of monastics that should be the elders doesn’t exist. Many monks and nuns do not wear robes: some because they have to work, others because of lack of money, some because they don’t want to be noticed. But this is not a good precedent, for it eventually will lead to a weakening in the Sangha.

While Tibetans in exile blame the Chinese communists for the destruction of their land, this is not the whole story. Unfortunately, many Tibetans cooperated with them in destroying the monasteries, either because they were forced or persuaded to or because they harbored jealousy or animosity towards the religious establishments. Many Tibetans came to see the Tibetan friend from India with whom I traveled. In tears, some of them told how they had joined in desecrating the temples years ago and how much they now regretted this. This was sad, but not surprising to learn, and I believe that Tibetans must acknowledge and heal the divisions existing in their own society.

In spite of all this, the monasteries are being rebuilt and many youngsters request ordination. The lay Tibetans are remarkable in their devotion. I marvel at how, after 25 years of strict religious persecution (one could get shot or imprisoned for even moving one’s lips while reciting mantra or prayer), now, given a little space, such intense interest and faith in the Dharma blossoms again.

Most Tibetans still have the hospitality and kindness for which they are so well-known. Lhasa, unfortunately, is becoming touristy, with people trying to sell things. But outside of Lhasa, especially in the villages, people are as friendly and warm as ever. They still look at foreigners as human beings, which is a pleasant relief, for in India and Nepal, many people see foreigners and think only of business and how to get money from them.

Pilgrimage and meeting people

When Zopa Rinpoche and the other Westerners went to Amdo, I went to the Lokha region with the attendant of one of my teachers. There I really felt Tibetan hospitality and warmth as I stayed in the homes of my teacher’s relatives and disciples in small villages. One very old man inspired me with his practice. He would do various Dharma practices the entire day, and I loved to sit in the shrine room with him and do my prayers and meditate in that peaceful atmosphere.

While I was staying at his house near Zedang, his son returned from the Tibetan-Indian border where there was much tension between the Chinese and the Indians. The young men in Zedang and other areas had been divided into three groups, which rotated doing one-month work shifts in the military installments at the border. The government gave them no choice about going. They had virtually no military instruction and were sent to the border unprepared. The son told us that part of his job was to look across the river to see what the Indian army was up to. But who was in the Indian army stationed at the border? Tibetans in exile. So Tibetans in Tibet could potentially have to fight against Tibetans in exile, although both groups were working in foreign armies.

For years I had wanted to go to Lhamo Lhatso (the Palden Lhamo lake) and to Cholung (where Lama Tsongkhapa did prostrations and mandala offerings). Both are in Lokha. Six of us did this pilgrimage on horseback for five days. (Incidentally, for some unexplainable reason, the government does not allow foreigners in this area. But somehow we managed to do the pilgrimage anyway.) I hadn’t ridden a horse in years and was quite relieved when they gave me a docile one. However, her back got a sore after two days, and so I was to ride another horse on the day we were making the final ascent to the lake (at 18,000 ft.) I got on, and the horse immediately tossed me off. It was on soft grass, so I didn’t mind too much. Later, when the saddle slipped and he reared up, I fell onto rocks. I decided to walk after that. But all this was part of the pilgrimage, for pilgrimage is not just going to a holy place and maybe seeing visions (as some people do at Lhatso). Nor is it only making offerings or touching one’s head to a blessed object. Pilgrimage is the entire experience—falling off the horse, getting scolded by a traveling companion, eating with the nomads in their tent. All this is an opportunity to practice Dharma, and it is by practice that we receive the inspiration of the Buddha.

As we neared Lhatso, my mind got happier day by day, and I thought of the great masters, those with pure minds, who had come to this place and seen visions in the lake. It was here that Reting Rinpoche had seen the letters and house that indicated the birthplace of the present Dalai Lama. After the long walk up, we sat on the narrow ridge looking down at the lake below. A few snowflakes began to fall—it was July—and we meditated. Later we descended the ridge and stayed the night at the monastery at its base.

The next day we headed towards Chusang and Cholung, places where Lama Tsongkhapa had lived. Even someone like me, who is as sensitive to “blessed vibrations” as a piece of rock, could feel something special about these places. Places like these exist all over Tibet, reminding us that many people throughout the centuries have followed the Buddha’s teachings and experienced their results. Cholung, a small mountainside retreat, also had been demolished. A monk living there had been a shepherd during the difficult years of the Cultural Revolution. He had also done forced labor under the Red Chinese. In the last few years, as government policy began to change, he raised funds and rebuilt the retreat place. How much I admire people like this, who kept their vows during such hardship and have the strength and courage to return to devastated holy places and slowly rebuild them.

It was at Cholung that Lama Tsongkhapa did 100,000 prostrations to each of the 35 Buddhas (3.5 million prostrations total) and then had a vision of them. The imprint of his body could be seen on the rock where he prostrated. I thought of the comparatively comfortable mat on which I did my meager 100,000 prostrations. I could also see figures of deities, flowers, and letters on the stone on which Je Rinpoche did mandala offerings. They say his forearm was raw from rubbing it on the stone.

Upon returning to Zedang, I saw some friends who had gone to Amdo. They had been to Kumbum, the large monastery located at Lama Tsongkhapa’s birthplace. It is now a great Chinese tourist place, and they were disappointed, feeling that the monks were there more for the tourists than for the Dharma. However, Labrang Monastery made up for it, for the 1000 monks there were studying and practicing well.

They said that demographic aggression had set in in Amdo. It seemed hardly a Tibetan place any more. The street and shop signs in Xining were almost all in Chinese, and in the countryside, one finds both Tibetan and Chinese Muslim villages. Some friends tried to find the village where the present Dalai Lama was born, but even when they learned its Chinese name, no one (even monks) were able to direct them to it.

Bus and boat led me to Samye, where the traditional pujas and “cham” (religious dancing with masks and costumes) during the fifth lunar month were in progress. People said that in the past it would take over a week to visit all the temples and monasteries in this great place where Guru Rinpoche (Padmasambhava) had lived. Certainly that is not the case now, for within half a day, we had seen all of it. I was dismayed to see animals living in one small temple and sawdust and hay piled up against the faces of Buddhas and bodhisattvas on the walls of another. Another temple was still used for grain storage, as so many had been during the Cultural Revolution.

Arising well before dawn one day, I walked up to Chimbu, where Guru Rinpoche and Yeshe Tsogyal had meditated in caves. There are meditators now living in the many caves up and down the mountainside. As I went from one to the other to make offerings, the meditators greeted me warmly, and I felt like I was meeting old friends.

With a few friends, I then traveled back to Lhasa and on to Pembo and Reting. Tourists usually go there in hired jeeps as no public transportation is available. However, a friend and I hitch-hiked (in Tibet, you call it “kutchie”), walked, and rode on a donkey cart. It was definitely slower and not so luxurious, but we got to know the people. The first night, after wallkng through wide valleys ringed by multi-layered mountains where the colors of the rocks varied from red to green to black, we finally persuaded the teachers at a village school that we weren’t Martians and we would appreciate being able to sleep in a spare room. The children, however, continued to think we were people from outer space and 50 or 60 of them would cluster around us to watch us do such interesting things as eat a piece of bread. Being able to go to the toilet in peace was considerably more difficult. This, too, was the first place I encountered children ridiculing us and being generally obnoxious. Unfortunately, similar episodes were to be repeated in other places. The good thing about it was that it made the I-to-be-refuted appear very clearly! Later I asked a Tibetan friend why the children were so rude to travelers, especially if they were Sangha. It hardly seemed to fit in with what I knew about Tibetan friendliness. “Because they don’t know the Dharma,” he replied. It made me think.

By this time, I was accustomed to the wide-open spaces and lack of trees in Tibet. How startling and enriching Reting appeared, situated in a juniper forest, which is said to have sprung from Dron Dompa’s hair. This area, where the previous Kadampa geshes had lived, had been leveled during the Cultural Revolution, and just in the last year, rebuilding the monastery began. Up the mountain was the site where Lama Tsongkhapa wrote the Lam Rim Chen Mo. Amidst manifold nettles, we prostrated to the simple seat of stones used to commemorate his seat. Further up the mountain is Je Rendawa’s abode, and around the mountain, Drom’s cave. Up, around, and up again we climbed until we came upon a boulder field. It was here that Lama Tsongkhapa had sat in meditation and caused a shower of letters to fall from the sky. I had always been skeptical about such things, but here they were in front of my eyes, many letters Ah, and Om Ah Hum. Veins of different colored rock inside the boulders formed the letters. They clearly hadn’t been carved by human hands. At the nunnery further down the mountain was a cave where Lama Tsongkhapa had meditated, and his and Dorje Pamo’s footprints were etched in the rock. Because I have deep respect and attraction for the simplicity and directness of the Kadampa geshes’ practice, Reting was a special place for me.

However, being there also made me recall the incident with the previous Reting Rinpoche and Sera-je’s fight with the Tibetan government in the early 1940s. This had left me perplexed, but it seems that it was a forewarning, symptomatic that amidst the wonder of old Tibet, something was terribly amiss. What perplexed me as well was why, after the Red Chinese takeover, some Tibetans joined in the looting and destruction of the monasteries. Yes, the Red Chinese instigated it and even forced many Tibetans to do it. But why did some Tibetans lead the groups? Why did some villagers join in when they didn’t have to? Why did some turn over innocent friends and relatives to the police?

Leaving Reting, we went to Siling Hermitage, perched on the steep side of a mountain. I wondered how it was possible to get up there, but a path led the way to this small cluster of retreat huts where we were so warmly received. Then on to Dalung, a famous Kargyu monastery that once held 7700 monks and the relic of the Buddha’s tooth. Need I repeat that it, too, had been demolished. An old monk there told us how he had been imprisoned for 20 years. Ten of those he was in shackles, ten more chopping wood. In 1984, together with twelve other monks, he returned to Dalung to reconstruct the monastery.

Upon returning to Lhasa, we made an excursion to Rado by hitching a ride on a tractor filled with ping noodles. Very comfortable indeed! A few days later, we got a ride towards Radza, this time in the back of a truck filled with watermelon. As the truck rolled down the road, we rolled among the watermelons.

We then began to slowly make our way back toward the Nepali border, visiting Gyantse, Shigatse, Shallu (Buton Rinpoche’s monastery), Sakya, and Lhatse. At Lhatse I visited the monastery and the family of one of my teachers. His sister burst into tears when she saw me for I reminded her of her brother who she hasn’t seen for over 25 years. But it was lovely staying with his family and meeting the abbot and head teachers who were Geshe-la’s friends.

In Shelkar, I stayed with relatives of another Tibetan friend in Nepal. Amala fed us aplenty and was constantly and lovingly barking out orders like an army sergeant, “Drink tea. Eat tsampa!” She far outshone even my grandmother with her ability to push food at you!

Behind Shelkar is Tsebri, a mountain range associated with Heruka and said to have been thrown to Tibet from India by a mahasiddha. It looks very different from other mountains in the area and has a variety of the most magnificent geological formations I’ve ever seen. This is another place that is spiritually very special for me. Together with an old Tibetan man as a guide and his donkey to carry our food and sleeping bags, my friend and I circumambulated this mountain range. We stayed in villages along the way, most of them making me feel like I had gone back a few centuries in a time machine. But the trip to Tibet was teaching me to be flexible. There were also a couple of tiny gompas with mummified bodies of great lamas that we visited along the way. Along the way we visited Chosang, where the previous life of a friend had once been abbot. The monastery was totally demolished, save a few rocks piled up to form an altar of sorts and a few prayer flags fluttering in the wind. Because this place was special to my friend, I sat and meditated there a while. Afterwards, when I looked up, there was a rainbow around the sun.

On we went to the border, stopping at Milarepa’s cave en route, and then descending from the high plateau of Tibet to the lush monsoon foliage of Nepal. Due to strong monsoon rains, a good portion of the road to Kathmandu had either fallen into the river or been covered by landslides. Nevertheless, it was a pleasant walk. Awaiting me in Kathmandu was a message from my teacher, asking me to go to Singapore to teach. Now at sea level, at the equator, in a sparkling-clean modern city, I have merely the memory and the imprints of this pilgrimage, which has changed something deep inside me.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.