What is Happiness? (Part 1)

Part 1 of 3

A series of talks on the theme of "What is Happiness" for the Mindscience Academy. Read the full article into which these talks were compiled on MindscienceAcademy.org.

Wherever we are in the world, we are in relationship to each and every sentient being. Why? We may live far away, and we may not see one another, but our actions influence the people around us who then influence the people around them. Through the ripple effect, things go out into the universe. Just being concerned about our own welfare and happiness, when we exist in relationship to all sentient beings who want happiness and not suffering, is a very limited view. When we open our minds and see how we’re related to everybody and care about them, then automatically we want to gear what we think and say and do towards the welfare of all beings. From a Buddhist perspective, the best way to do this is to attain Buddhahood. Thus, we aspire to complete the path and become fully awakened, and that is our bodhicitta motivation.

What we think is happiness

I’m very happy to be invited to contribute to this forum of discussion between scientists and Buddhists. The present theme, as I understand it, is What is happiness? This is a very interesting topic because we all want happiness and we don’t want suffering, but I think there’s a lot of confusion in the world about what exactly happiness is.

In one of the Buddhist recitations that we do on the Four Immeasurables, we talk about love, compassion, joy and equanimity. The first line of love says, “May all sentient beings have happiness and its causes.” We say that, but what is happiness and what are its causes? This is where I think there’s a lot of confusion in the world because our main view is that happiness comes from outside of ourselves. It comes from sense objects. We see things or people that we like, and that’s happiness. We hear music and sounds and sweet words of encouragement and love and so on with our ears, and that’s happiness. We smell sweet smells, and that’s happiness. We taste good food—especially good Italian food because it’s delicious—and that’s happiness. We feel nice things on our body, the right temperature and so on, and that’s happiness. So, we usually think of happiness as sense pleasure.

The difficulty with that is that first of all, we’re relying on external objects, and we cannot control everything in the world. We try to, and we want to control our own immediate environment so that the sense objects we like come our way and the ones we don’t like get pushed away. We try to control that, but we can’t because people do what people do and things have their own system of cause and effect that we can’t control. That’s one problem with relying on external things. A second problem is that even if we could get everything we wanted, all those things are impermanent: they’re changing moment-to-moment, and they go out of existence. So, if we make our happiness dependent on things we can’t control and on things that by their very nature are changing all the time, how are we ever going to arrive at the happiness that we want? That’s one problem.

Another problem is what is the feeling of happiness? When we talk about love, which is wanting sentient beings—ourselves included—to have happiness and its causes, we often think that the feeling of happiness is this kind of giddiness. It’s like, “Oh, I won a prize! I got a promotion! Somebody acknowledged how wonderful I am! Things turned out the way I wanted! This is exciting!” It’s this giddiness. From a Buddhist viewpoint, that might feel good for a while, but again, it’s relying on external things, so it’s impermanent. The more we rely on that, the more problems we have when it changes. We look at external things that make us happy and you have your daydream about how if only this would happen then I would have happiness. But imagine having that thing that you think is happiness all the time.

In our culture falling in love is often viewed as the ultimate happiness. This person loves you. They think you’re fantastic, and you have your daydream where you go skiing, or you lie on the beach or what have you. But the thing is, imagine that person you think is so absolutely wonderful, that’s going to make you happy for ever and ever and ever. Now imagine being with that person for 24 hours straight—no breaks. You’re chained together. After 24 hours, are you still as happy as you were in the first few minutes of being with them? Or are you thinking, “I’d like a break. I need some time to myself. I need time to think”? This isn’t really happiness. And anyways, this person also does all these things I don’t like. So then your happiness falls apart.

Another problem with this kind of happiness that depends on external things is that in our minds we think “more and better” is the way to go. “I want more money. I want more esteem. I want more status. I want more love. I want more appreciation. I want a better house. I want a better partner. I want a better this and a better that.” So, even when we get what we want, the mind is in a state of continual dissatisfaction because our mantra is “More and better, more and better: I want more and better.” And even if we get more and better we’re still dissatisfied because we still want more and better. Do you know anybody who has enough money? Nobody has enough money. You can always use more. So, there’s this state of dissatisfaction.

True Happiness

I just shot down everything we all thought was happiness, so then what does the Buddha say? There’s got to be happiness somewhere. Here we’re looking at a sense of happiness that comes from two factors. One is having a peaceful mind, and two is having a sense of purpose in our life.

So, when it comes to having a peaceful mind, what makes us peaceful? More and better doesn’t, but what makes us peaceful? When I look at my own experience, when I act according to my own values and my own principles, when I live an ethical life, then my heart is peaceful. When I don’t live an ethical life my heart is not peaceful. And the thing is that no matter how much other people praise us and tell us how absolutely wonderful and magnificent we are, and no matter how much another group criticizes us, at the end of the day we’re the ones who live with ourselves. We’re the ones who know what our actual motivation is. We know when we have a rotten motivation, when we’re being self-centered, when we’re manipulative, when we’re taking advantage of other people to get what we want. We may get what we want on the outside, temporarily, but inside, the mind isn’t peaceful.

When we act according to our own values—when we’re honest, when we are truthful, when we speak with kindness, when we go out of our way to help others—then we feel good about ourselves. If we refrain from harming others and act with kindness toward them, but we do it expecting a thank you then we’re falling into the same trap of relying on something external to ourselves. But from a Buddhist viewpoint, when we live according to our own values then there’s a sense of internal peace and kindness to others. It’s the feeling that we get from connecting with them and making a positive difference in somebody’s life. That feeling is its own reward. We don’t need external thank yous and plaques and certificates to be announced in front of the world about how wonderful we are, because there’s this sense of peace inside our own heart.

And the second factor is having a sense of purpose. This is not just any sense of purpose, because we can have a sense of purpose of “I’m going to swindle somebody to get what I want” also. No, I’m not talking about that. When we have a sense of purpose of making a positive contribution to society or making a positive contribution to somebody else’s life, even if it’s something small, that sense of purpose brings a good feeling to our heart. We’re not wandering all around in our life questioning, “What am I doing?” We know what we’re doing. What we do in Buddhist practice is we set our motivation as soon as we wake up. We say, “Today, as much as possible, I’m not going to harm others. Today, as much as possible, I’m going to benefit them. And today, as much as possible, I’m going to try to increase my love and compassion for every being in an equal way.” This is not just people I like, but it’s to have a sense of our place in the world even with living beings who we don’t know.

In other words, we are aware that our own actions matter and they influence the people around us who in turn influence other people and so on. You have the ripple effect. So, when we have a sense of purpose to create joy in this world and to alleviate misery in this world, then we know what we are doing is something beneficial and that sense of purpose brings fulfillment. I think from a Buddhist perspective, the sense of fulfillment is what we mean by happiness. It’s not the giddy feeling of, “Oh, good! I’m mentioned in a journal. I got an award. I got a promotion. This is fantastic! The person I love called me—yippee!” No, it’s not that. What brings that sense of fulfillment is having a purpose that goes beyond our own limited welfare. It’s having a purpose to contribute to the well being of others.

You might ask, “What in the world can I contribute?” We all have our own talents. We all have our own fields of knowledge, and contributing to other’s welfare in that way gives us a sense of purpose. Even having the purpose of being kind on a moment-to-moment level with the people around us is a sense of purpose, and that can make a difference.

Here’s just a small story to illustrate this because we don’t actually always know how our actions are going to affect others. Sometimes we can do things that really have quite a profound effect. A friend once told me that when she was younger she was very confused about life. She was very depressed, and she was almost to the point of considering suicide. She said one day she was just walking down the street, and somebody who she didn’t know was coming the other way. That person smiled at her, and she thought, “Wow, somebody I don’t know smiled at me.” She said that all thoughts of suicide vanished at that moment because there was a connection with another human being who she could tell wished her well even though that person didn’t even know her. So, these small things that we can do on a moment-to-moment basis can really create happiness and peace in other people’s minds and bring us a sense of fulfillment. What we do—even these small things—has a positive effect on other people.

So, in brief, that is what happiness is. Love is happiness. Love is thinking, “May all sentient beings have happiness and its causes.” That feeling of fulfillment is happiness, and it lasts. It isn’t open to the upheaval of the atmosphere that we’re in and the circumstances that we’re in. So, again, the causes of happiness from a Buddhist viewpoint are acting in an ethical way, living according to our values and principles, caring about other people, and opening our hearts to other people. That causes happiness now. It brings a sense of purpose and a sense of peace, and then it creates happiness in the future for not only others but also ourselves. This is really something to think about in our lives.

Part 2 of this series:

Part 3 of this series:

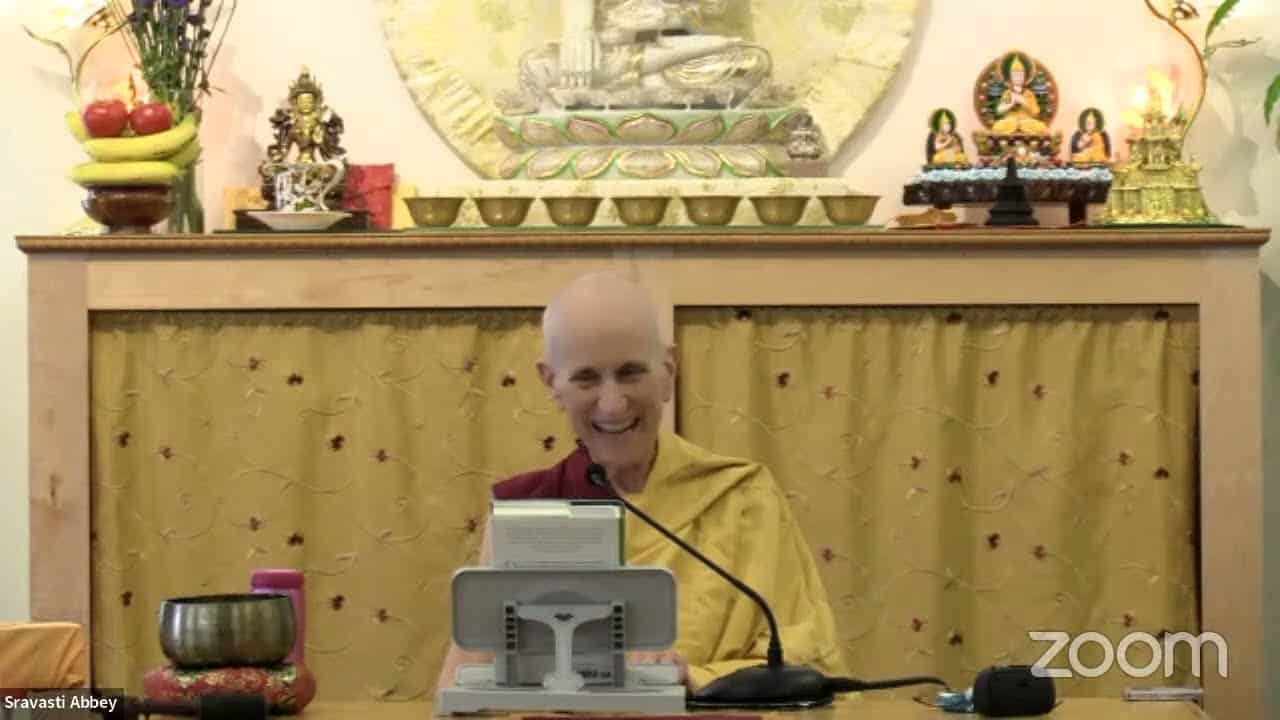

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.