What is Happiness? (Part 2)

Part 2 of 3

A series of talks on the theme of "What is Happiness" for the Mindscience Academy. Read the full article into which these talks were compiled on MindscienceAcademy.org.

I would like to do a case study, so to speak, of what is happiness. On the flight back from Taiwan to the States, the film Oppenheimer was playing. I’m never going to go to a movie theater to watch this, so I put on my headphones and watched the movie. It’s a real study of being conflicted. It’s a study of when your mind is conflicted about your purpose, your ethics, your motivation, and your intention. There are a couple of scenes that really stick in my mind. The first one is when they actually exploded the bomb at Los Alamos to see if it would work. They were all hunkered down, and everybody was nervous. There was one guy with his thumb over the button to call it all off, but he knew everyone was excited to see if all their work was going to lead to an explosion. So, he doesn’t call it all off, and then there’s a countdown, and—boom! You see this huge mushroom cloud go up, and everybody is shocked at first and feeling the force of the wave of energy. And then they all cheered. “What we did worked! Look what we did! This is a magnificent scientific discovery of the energy of the atom. We’re going to use it to stop the war!” Everybody cheered, but Oppenheimer wasn’t sure. He had an idea of the damage that this thing could do, and so he was like, “Oh, now the world is in a different place. We have the ability to destroy ourselves. What in the world have we done?” But when everybody else around him was cheering then he started cheering, too. So, at first there was this sense of conscience, this uncertainty of what he had done. But when everybody else was happy and cheering then he got involved with cheering, too. But the thing is, at the end of the day we have to live with ourselves, and it was hard for him to live with himself after that.

The next scene that influenced me was when he was in a huge auditorium and there were all these people cheering for him because they were all so proud of what he had done. The film shows how before he went in he was not happy, because he was aware of how many people were killed in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At that point they didn’t even know the long-lasting effects of the radiation on the area. They didn’t even know the effects of exploding the bomb in Los Alamos, or how all the testing of the hydrogen bomb in the Marshall Islands would affect the health of those in the area. They didn’t even know any of this at the time. So, he was again conflicted: “Yes, we won the war, but at what cost did we win the war?” But then everyone in the auditorium was shouting for him and standing up and applauding, and it’s the kind of thing that anybody would love because everybody thinks you’re wonderful. “Look what you did! You won the war.” Then they were saying they wished they could have done that to the Germans as well. Everybody was so happy and shouting, and then because of attachment to reputation and because others were telling him he was so wonderful, he got into it as well. Then he felt good—temporarily. But again, at the end of the day, in his own heart, he was conflicted.

That really made me stop and ask, “What does a good reputation matter when you’re not at peace in your heart?” It doesn’t matter how many people applaud you and shout your name. We’re a living being, and we have a conscience. We often bury our conscience, or we often don’t even call up our conscience or our sense of ethical principles, but they are there. So, when we act contrary to that, there’s no peace in our heart. We start to question what our purpose is and what we have done. We see that our actions influence others, and in the case of these scientists, their actions certainly did influence others.

We’re at a similar point in history right now with artificial intelligence, which like the internet, everybody was so excited about. “It’s going to bring people together and allow us to share information and revolutionize everything. It’s going to make everything so much better. AI is so fantastic!” And what do you have as a result? Yesterday I was reading an article about how you can take a picture of a woman or girl at school and there are AI programs that will show what that person would look like naked. So, teenage boys are putting things on social media of their female classmates that show what they would look like naked. The girls are upset, of course. And there’s no control over this.

Does this bring happiness? And what else are we going to use AI for? Who knows what else. They might use AI in warfare thinking of how they could approach the enemy, how they could kill someone else. They might start out thinking of how to win a war, but then things might get out of control. I wonder how much AI is being used in what’s going on with Israel and Hamas right now. Israel bombed some cars that were bringing food into Gaza from The World Kitchen, and seven aid workers were killed and all the food and cars were destroyed. I wonder if AI was involved in that miscalculation. Israel later said there was a mistake, there was misinformation. They acknowledged making a mistake. I wonder if AI was involved. That’s just my thought. I’m not accusing them of anything because I don’t know.

Keeping an ethical focus

What I’m saying is that when we look at scientific discoveries and so on, we need to call forth our sense of morality, our sense of ethical conduct. We shouldn’t be so entranced with what we as human beings can discover about the natural world. If we don’t think about what these discoveries can be used for, and if we don’t have ethical conduct in place in our societal institutions, then these magnificent discoveries will be abused and will damage people. If we’re talking about happiness in the long term, which involves everybody’s happiness, then we have to think about the consequences of what we’re doing in science. Then the question comes up of “Why should we care about everybody’s happiness?” Like in the film, they won the war. There was the view that we were the morally correct people who defeated the bad guys, so why should we care? But what were the lasting effects of those things, and were we peaceful in our own hearts? When we harm other living beings do we then create a peaceful society?

Having grown up in the middle of the Vietnam war where we were told we were killing people so that we could grow up free of communism, as a young person I thought that didn’t sound right. We were harming people so we could be happy. What? How does that work? When we harm people then we live surrounded by people who are miserable, and people who are miserable let us know they are unhappy. As a society, when we don’t take care of the most vulnerable people, and those people are miserable, we live in a society where we are influenced by those unhappy people. And that infringes on our own happiness. That’s why His Holiness the Dalai Lama always says, “If you want to be selfish—if you really think that self-centeredness is the way to happiness—the best way to be selfish is to take care of others.” Why? Because then we live near people who are happy. They help us, we see happy faces, and there is peace in society. When we take advantage of people then we live near people who are unhappy.

This is coming up in the news a lot because now many localities are making laws against encampments of people who are homeless. Society does not take care of people when they lose their job and then they can’t pay rent or their mortgage, so they end up on the street. We don’t take care of people with mental and physical illnesses, so they also end up on the street. So then you are surrounded by people who are unhappy. The last time I was in Seattle, I saw tents and homeless people sleeping near the highway, and when I visited Santa Monica I saw homeless people on the beach as well. Now localities are saying that homeless people are getting in the way of our happiness, so they are making laws that criminalize sleeping on public grounds. They are going to start arresting people who are homeless and giving them fines.

There was an interview with one woman who was homeless, and she got tickets for sleeping out in public. Each ticket was three hundred dollars. She’s homeless. How can she afford a three hundred dollar ticket, especially when she gets one every day for sleeping somewhere? Then people complain that they don’t want homeless people around them because they will steal from us or harm us. We have to walk over them to get into the businesses where we want to do our shopping, so we criminalize homelessness. Something is very wrong about that. When we don’t take care of others, when we don’t have a sense of responsibility, it adversely affects us here and now in our society right away. And then what do we do? We’re meaner to them. Instead of doing something to help them we are meaner, and then what happens? They move from one homeless place to another, or they break into houses and steal because they need to get some food.

My point in discussing all of this is that when we act with a sense of ethical conduct, a sense that our actions influence others and therefore we care about others and act accordingly, then we do things that can bring peace in other people’s lives. Then just in terms of this life only, we’re better off. And in terms of the karma we create and future results we will experience, we have a sense of peace in our own hearts because we will know that what we’ve done is good, and we’ve connected with others. There’s a sense of satisfaction and fulfillment that doesn’t need other people’s applause and awards in order to be felt. So, helping others also helps ourselves. That sense of happiness is much more significant than the giddy happiness of “I got what I wanted!” That’s something for us all to think about.

Part 1 of this series:

Part 3 of this series:

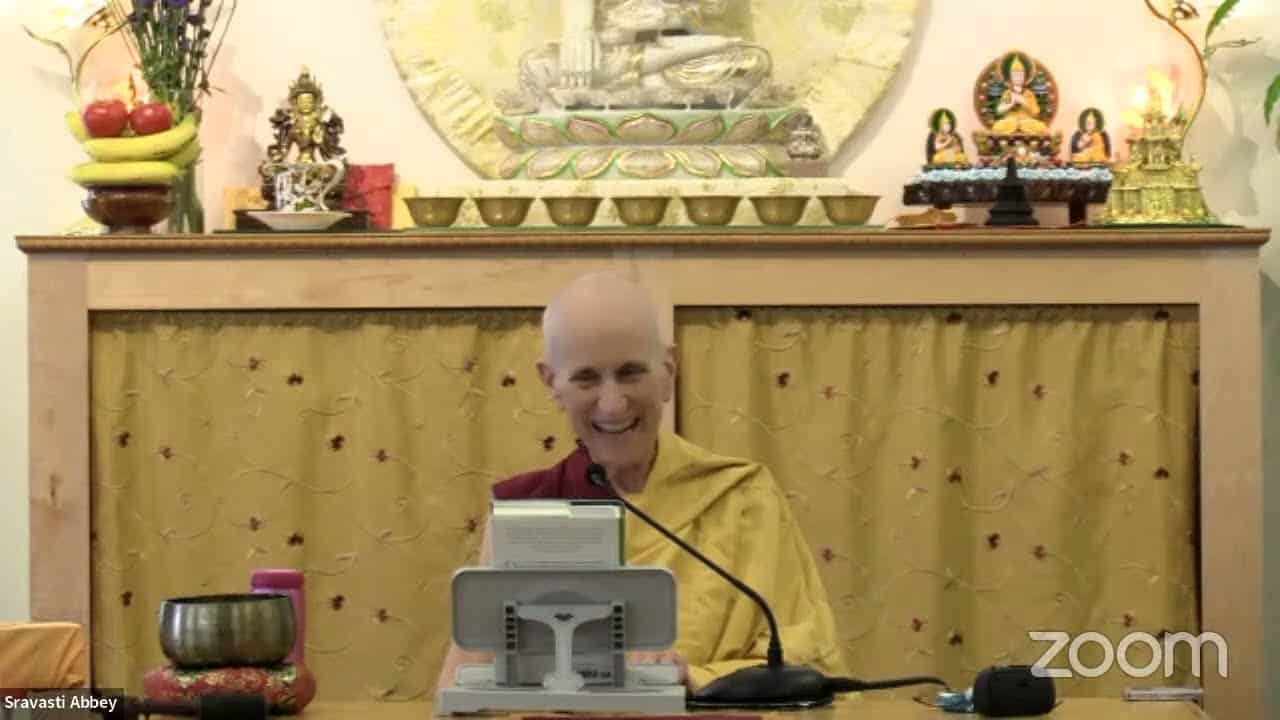

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.