Letting go of identities

04 Vajrasattva Retreat: Letting Go of Identities

Part of a series of teachings given during the Vajrasattva New Year's Retreat at Sravasti Abbey at the end of 2018.

- Meditation on letting go of identities

- Questions and answers

Imagine Vajrasattva on the crown of your head, with his body made of white light. Really focus on him being made of light, not something solid. Then, Vajrasattva melts into a ball of light that comes into you through the crown of your head, and as soon as Vajrasattva, this ball of light, enters you, your whole body dissolves into light. Think that your whole body is simply a ball of light. As a ball of light, you have no race, you have no ethnicity, you have no sex, you have no gender, you have no nationality, you have no sexual orientation, you have no state of being young or old, of being attractive or unattractive, of being fit or unfit, of being healthy or unhealthy. Think, all those identities that you hold onto based on your body are now not there. It’s just a clear ball of light, so those identities are impossible to hold with having a body that’s a ball of light.

Imagine functioning in the world without those identities that are based on your body. Men no longer have extra physical strength or height or louder voices. Women no longer have to be concerned about sexual abuse or about being overpowered in a meeting by men. You have no gender and you relate to the world that way. Think, what would have to change in your mentality to let go of your gender, your identity? Not that you became another gender, but that there just was no gender identity at all in the world. How would your mind change?

Because your body is a ball of light, you have no race, you have no ethnicity, and neither does anybody else. How would your mentality change if you functioned in a society where there was no race? Not where you were a different race, or there are dominant and lower races or anything, there’s just no race, no ethnicity. How would the way you feel about yourself change? How would the way you relate to the world change?

Now look into hearts of all the other beings near and far who all have bodies made of light. What do you see in their hearts? What is most important to each and every living being? It’s their wish to be happy and safe, and their wish to not suffer. Focus on that, because that pertains to every living being, doesn’t matter what kind of living being. It’s the most important thing in everybody’s mind, we’re all completely the same in that regard.

If everybody’s the same in wanting happiness and not wanting suffering, and nobody has any identity based on their body, nationality, or whatever, then can you generate great love and great compassion for all of them without any discrimination between friend, enemy, and stranger? There’s no fear of any other living being at all and no sense of being different than any other living being. Then, think that your body, which is a ball of light, slowly takes the form of Vajrasattva, and as the wise and compassionate being Vajrasattva you relate to the rest of the world.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): What changed in how you saw yourself and how you related to others?

Audience: It didn’t matter which identity I chose, it was like each one came with a script and the script absolutely limits how I can function. It absolutely sort of traps the mind in a certain view, and then the more identities we have—of course we’ve got many—the more we’re squeezed into this little tiny crumple of paper that can barely function. Seeing the world from that point of view that’s so limited is a tragedy.

Audience: What came up for me was very similar to what was just shared, it felt like it kept me in samsara. That was my takeaway. I did have a question this morning and it was off of you sharing your story about deconstructing identities and I’m curious to see, did that also include deconstructing the identity of being a Buddhist?

VTC: Yeah, also your identity as a Buddhist. All the identities.

Audience: I noticed that at first, I was grasping at the identities as they were dissolving and I was thinking, “Oh, well if I’m not young, then I’m old. If I’m not this, then I must be that. And I don’t want to be that.” But it was such a relief. I was looking around, I was imagining the whole room, “Well, I can’t judge people.” I wouldn’t judge people, I wouldn’t judge myself. I wouldn’t be comparing myself to others, and it was just this huge relief and much easier to develop equanimity and love and compassion.

Audience: I noticed a lot of fear and isolation that comes with these identities and the comparing and being completely different, [thinking] there’s nothing that’s common between us. Then I did have this very expansive feeling of equanimity and it was amazing. Once that was dissolved, it was quite an experience.

VTC: It’s amazing that all these identities are made by the mind. They’re all constructed by thought. There’s no other reality to them.

Audience: I realize that a lot of the communities I am part of would kind of lose their boundaries because there would no longer be something to distinguish who can be and who cannot be a part of the community, so all of these walls would come down.

Audience: I have to share this one experience I had. When I was in my early twenties I met a guy named David and I was kind of attracted to David. A few weeks later I saw David and David was Daviade. And I was like, “You’ve changed… I mean, I had a crush on you!” And now it was Daviade and I was really stumped. It was really a confusing thing for me and of course we talked it all out and I decided it was way too confusing for me to get involved with, but it was an interesting thing to have someone change from day to day or week to week.

VTC: Yeah, and how much we relate to other people based on identities that are based on the body.

Audience: I have a question about an identity that is linked to an actual phenomenon, an experience. For example, birthing a child. I had not birthed a child so I’m not a mother in that sense, so I don’t necessarily carry that identity right at this point. Or someone who actually fathers a child. I understand it’s conceptual and somewhat created by our culture, but can you talk a little bit about that?

VTC: Well, there are mothers and fathers conventionally, but again, it’s identities that are formed by conception. A mother is this, a father does this. Am I understanding your question?

Audience: Yeah, I didn’t actually put it in a question Maybe it’s not well formulated in my mind, so I’ll keep listening.

VTC: I haven’t had a child either, but even if somebody’s had a child. You aren’t having a child all the time.

Audience: I thought I’d just comment. I have had two babies and it’s interesting because being here is really hard because I am away from them and they are five and seven, I should be old hat at this. But it’s funny because when I sit and meditate, it is such a strong part of my identity. I’m a mom, I‘ve got two kids, they are waiting for me at home, all these things. At the same time they could disappear, they could not exist anymore and that’s a really interesting, powerful thing for me that I’ve thought about prior to this conversation. I don’t know if that answers your question but yes, they have become a huge part of my identity and being a mom is huge but also at the same time it’s totally conditional and could disappear at any moment. So, it is a strong identity but like Venerable says, we’re not constantly in labor so that part goes away and then even your kids can go away, so it is in the moment a strong part but at the same time very gradual changes.

VTC: The identity as a mother is going to change as you get older and as the kids get older. I think that’s one of the things that sometimes creates difficulties in families, is the actual circumstances change but the mind doesn’t. Your kid is 20 years old and they’re still 20 months in your eyes.

Audience: For me, after a few minutes I went to a place of, “This is really great, and I feel really open and connected.” But I also was thinking about like, “I’m going to get bored, who’s going to push me to grow?” I felt like I might become like an amoeba, just kind of bounce around with everybody. So I had that experience of worrying about, “How am I going to grow and learn and things if we’re all the same?” That was one of my experiences.

VTC: As if the only way to grow and learn is to hit against something else.

Audience: I had a similar experience. At first it was just very pleasant and I was thinking of equanimity and everything was beautiful. Then I thought, “How am I going know who everybody is?” and I started making them different colors, and I went, “Oh my goodness.” I had to end the meditation.

VTC: It’s quite interesting, this one. I remember Lama always talking about how we discriminate this and that. We’re always discriminating this and that, all the time, this and that, to the point that when we start thinking about the emptiness of an inherent existence, it’s very scary. The realization of what will liberate us from samsara scares us and terrifies us because we’re afraid that we’re going to disappear and everybody else is going to disappear. Then who am I? What am I going to learn? What am I going to do? What’s going to be interesting to me? We have to have all these different-colored differences but when our discriminating mind starts focusing on all these differences, what do we come up with? Conflict. It’s interesting that in some way, we’re attached to conflict because it makes us feel alive. We’re attached to being different and feeling like we don’t belong because that way we know we exist. Yet, this mind that grasps the self as some kind of independent thing is the root of all of our misery. Isn’t that interesting, how attached we are to the root of our misery? How terrified we are of knowing the actual nature how things exist, how we ourselves actually exist. When you see that, then you understand why the Buddha said that sentient beings were ignorant. Look at the depth of our ignorance, that we are afraid of the liberating path, that we’re afraid of the truth. This is what it means to be an ignorant sentient being. If we dissolve into emptiness, life is going to be so boring, because our mind of attachment thrives on differences. The mind of attachment says, “Oh, this is different than that so I like this and I don’t like that, and I want this and I don’t want that.” That very attachment to all the differences also limits us and keeps us in prison and makes us pretty miserable.

Audience: Could you offer some clarity on the identities that Buddhas hold in terms of their manifestations? I know that a lot of that is from our side and they’re benefiting us but how does that vary?

VTC: They’re appearing in different forms, for our benefit. I don’t think Manjushri’s going there and saying, “Look, I’m a guy so Tara, shut up, because I’m going to run this [show] and I don’t want any feminists mouthing off, so Tara, Vajrayogini, I don’t care if there’s a hundred and eight Taras, shut up.” I don’t think that’s going to happen. When they talk about how things actually exist, they say, “by merely name.” That means that there’s some basis of designation that itself is actually pretty amorphous, but our conceptual mind puts things together and gives it a name, and as soon as we give it a name, whoop, it gets concretized. For a Buddha, you give it a name, it doesn’t get concretized. It’s just a name is some easy way to communicate with things.

Audience: When [inaudible] was here last time, didn’t he talk about a sutra in which there was a being who showed up as a female and one of the monks was giving her a hard time and she goes, “What do you think a body is?”

VTC: Oh yes, that’s the sutra… [audience responds: Vimalakirti.] It happens in Vimalakirti, it also happens in the Sridevi-something sutra.

Audience: I had one other comment. As soon as you said that, I felt a lot of unease because I think people who are not part of the dominant culture feel like they’re being erased a lot. Like, “I don’t see color” and all that kind of stuff. Then I said, “Okay, switch this. You think you’re just going to become this light ball and it’s just going to be the same, so what privileges and smugness am I going to have to give up if I’m just a ball of light and not this person who has assumed all this time that I get my way?”

VTC: I mean, everybody loses their identity, and like I said, if we cling to our identity this meditation can drive you nuts, especially in a world where we are so identity-conscious now. So identity conscious. That’s why I think some people could go, “I’m a minority, you’re erasing my identity.” Some of you may remember Marcia, an African-American woman who came to Cloud Mountain retreats. She and I were friends and we were taking a walk one day and talking about race and I was asking her, I can’t remember exactly what, but maybe it was something about how she felt being the only African-American person at that Cloud Mountain retreat. And she said—because you know how we are and how I lead things—she said, “It was the first time where I was invisible to myself.” For her, that was a big relief, to be invisible to herself, to not keep yourself apart because of holding on to a certain identity. It’s interesting to me because I’ve lived in many cultures where I have not been part of the dominant group. When you live in a Tibetan monastic culture, you are very aware that you are not part of the dominant group and that you are definitely lesser than and especially being a woman. I think it actually can be quite a huge relief to be invisible to ourselves. Now somebody’s going to get mad. That’s okay.

Audience: I’ve been thinking about this since the session this morning. I was thinking about the term dependent arising, how as we’re talking about identities, there’s many reasons that it seems more prevalent now, but I don’t think it is as prevalent, it’s just more publicized. Also, I think one of the dynamics that also keeps this going is that we relate to people as if they were that thing, so we further reinforce that. Let’s say it’s groups that are marginalized, so we reinforce that marginalization with our actions and our words. It keeps reinforcing itself because you’re saying, “You’re this” because of the way maybe you’re looking at them or treating. I think it could cause folks to feel like they are the ones who’ve been pushed into the box. They’re just saying, “We just exist and we want to be treated equal but that’s not how we are being treated.” I think for me, it’s important that we examine how we also treat others, like how we’re reinforcing those ways that we think of other people, because I think we otherize people a lot.

VTC: We otherize people based on our clinging to our identity because if I am this, then other people are that. We treat other people in a way that reinforces their identity, but we also reinforce our own identity. Then we’re stuck in pain and suffering because everybody is saying, “Hey, I’ve an identity and you don’t understand it.” What I’ve been saying about how I find it so interesting—and this is going to push buttons—white men are now a discriminated-against group. They’re complaining that nobody sees them, there are so many stereotypes, there’s all this prejudice against them. That’s where we get the alt-right and these guys in Charlottesville. They’re holding on to an identity and of course putting identities on other people. That’s why I think it’s really important for all of us to really understand that our identities are created by our own mind. Other people may treat us in a certain way, [but] we have the choice of buying into it or not buying into it.

I know that as children we don’t have an ability to discriminate, so what we’re told as kids we believe. This is regarding all sorts of things, not just identity, but all sorts of things. The nice thing about getting older is we can look at what we’ve been conditioned to believe and we can say, “Do I want to continue to believe that?” I think it’s important to always realize we have a choice. It can be difficult to find the choice when we have a lot of conditioning around us telling us the opposite. When we have social conditioning or family conditioning, and when we’ve bought into that conditioning, whatever it is, it’s hard to find the choice. But, if we can stay quiet—and I’m talking from the Buddhist viewpoint, which deconstructs identities, doesn’t form them. I’m not talking from an activist viewpoint, I’m talking from a Buddhist viewpoint—and if we realize there’s a choice in there then we can see, other people may see me that way, that doesn’t mean I have to see myself that way. Other people in my group may see other people a certain way, or my family may see people in a certain way, but that doesn’t mean I have to see other people in the same way that my family does. Before we came into here, Venerable Pende was talking to me about being Vietnamese-American. Would you share with the group what you said to me? I’m putting her on the spot. It was very beautiful what you said.

Venerable Pende: I think instead of holding my identity very tightly, I’ve been practicing to combine the best of Vietnamese culture and western culture. Living at the Abbey has given me the precious opportunity to connect to all the guests from all around the world, so I get the chance to learn from a lot of people and that to me is very beautiful and very powerful.

VTC: She also said, “I don’t have to always be around Vietnamese people and think like Vietnamese people. I can just be a person without clinging to a certain nationality.”

Audience: I just wanted to add this one other thing, which is, also in our quest for equanimity and getting rid of identities, to also at the same time realize conventional existence and conventionally how people are treated according to how they are perceived. I’m just adding that because I’ve encountered in my experience people going, “Oh, we are all one” and it’s like, “Yeah.” But, there are people who are suffering real consequences like getting killed, et cetera, because of who they are perceived to be and all that other stuff. I just really wanted to add that, to not erase that there are things that exist but it’s the hanging onto them that I think creates the problems.

VTC: Exactly. In samsara, what you said is completely true. The thing I’m saying is, do we want to keep our mind in samsara? The world around us keeps their mind in samsara. Do I want to join them? No. I have too much of my mind in samsara as it is, I don’t want to solidify that. But, I recognize other people have that.

Audience: I had a question, actually, it sort of ties into that. I am not a black person, I was never a mother, and they have a shared knowledge that I don’t necessarily have. So, even if you don’t construct an identity out of it, they can look at each other across the room and make an instant contact and kind of understand each other, but I cannot. Maybe you could comment on what do you do with that?

VTC: See, this is part of the thing. If we construct an identity of, “My identity is like this. You look like me so you have a similar identity, and you don’t look like me so you have a different identity,” and when we look at people what we see is the differences, then everybody is going to be quite different and it’s going to be really difficult. That’s why in the meditation I had everybody look into every single living being’s heart, human being or not human being, in this country or not in this country—in other countries the whole thing of race is very, very different than it is in this country—and to look into everybody’s heart, and, “Hey, we all want happiness. We all don’t want to experience suffering.” If we went around the room, I don’t care what color people are, or what ethnicity, or what sexual orientation, or whatever it is. Everybody has some suffering and feels left out and misunderstood. I guarantee that.

This was my big discovery after I left high school. I don’t know about your high school but [in] my high school there were cliques. There were the cliques of the sosh’s in my high school. The sosh’s were the social kids, the football players and the cheerleaders. They’re the ones who were the homecoming queen and the homecoming king, and they’re the ones who were really popular, who everybody wanted to look like, to be like, and they set the standard for the school. Remember in high school? Wasn’t it the same for everybody? Now, I don’t know about you, but I was not one of those kids. I was some kind of other kid. A little bit nerdy, a little bit this, a little bit that, I didn’t really belong anywhere. I looked at those kids and thought, “Wow, they really belong, they’re the in crowd, they don’t feel insecure and excluded and left out like I feel.” Then, when I went to college, I talked to some of the kids I went to high school with and I talked to kids who had been the equivalent of sosh’s in their high schools. They told me that they felt like they didn’t belong, that they were left out, that they weren’t the “in” kids. I was shocked. It was like, “But wait, you’re the ones everybody looked up to, everybody thought we should look like you, and act like you, and to be like you, and you’re telling me that you felt like you didn’t belong and you felt left out and insecure?” I was shocked.

That opened my mind completely to a thing of, don’t judge other people and don’t think I know somebody else’s internal experience. All of us can go around. Some people have health concerns that nobody else knows about and they feel discriminated against because we treat them like they should be the same even though they have health concerns. I mean, every one of us can find I’m sure at least five ways in which we do not belong to the group that is sitting here in this room. We can separate ourselves out and other people can look at us and separate us out too, why we’re different. From the Buddhist viewpoint, what we want to do is look beyond those fabrications that are based on the foundation of grasping at true existence, that are based on ignorance, and look into everybody’s heart and see everybody simply wants to be happy and not suffer, and everybody deserves to be happy and not suffer. Basta, finito. That’s the way, as a practitioner, I’ve been training my mind. So yes, all the rest of this stuff, the craziness in samsara, exists, and people are hooked into it and they suffer because of it. I’m not negating that. I’m saying I don’t want to jump into the filth. I’m doing my best to recondition my mind.

Audience: I can offer two different opponent opinions at the same time. [laughter]

VTC: Very well put, because that’s the way we are often, isn’t it? We believe two opposite things at the same time, almost.

Audience: I was just thinking how pretty much during my life—and I guess I’ve been in lucky circumstances—I’ve never really felt the strong identification with gender. There were very female sorts of female, more male, it was like a spectrum. It’s only when I became monastic that I was pushed into this identity of being female. It’s so confronting because it is when leaving behind the household life, leaving behind the worldly life, I’m confronted with this very worldly forced identification.

VTC: See, I know what you were talking about, so you and I understand each other in a way that nobody else… except they haven’t lived in India. Some of the ones here, they haven’t lived in India and had our experiences. We really bond because we understand. Nobody else understands. Those monks over there? I don’t know.

Audience: We are very special in terms of gender. We are very tolerant and we’re still different.

VTC: You mean you and I are different? I can’t be Dutch? You can be American! We’re the greatest nation in the world, you don’t want to be part of us? Oh, you want to be Russian!

Do you see what we do? It just gets to a point where it’s like, give me a break already. Just what you said, I’ll talk about our identity that nobody else understands and how we’re victims of the patriarchal religious structure that sees us as inferior, and it’s true, they do. I had a friend, an American friend, who studied in the dialectic school just a few years ago, so this is a recent story. In the dialectic school, his teacher—it was a Tibetan monk—asked the other people in the class—who were all Tibetan monks except my friend who was American and there was a European nun—and asked them, “Who is superior, men or women?” All the monks said men are superior and women are inferior, except the European nun and my American friend who was male. You see, it proves they are discriminating against us and we have no chance and we’re suppressed. I can tell you gazillions of stories, well maybe not gazillions, but many stories of the prejudice I faced being a woman in the Tibetan community and being white in the Tibetan community. You know what? I am so sick of it. I am so sick of holding that identity, and feeling discriminated against, and I’m not given equal opportunity, I’m so sick of it. It gets you nowhere you could run around in circles. We have all the reasons to prove our case. So what? I’m sick of putting myself in that box. They put me in the box, what to do? I just go about and do my own thing. I don’t have to buy into their box. When I live in that culture, I’m limited by what I’m able to do but there are also ways to get around things. The biggest thing to get around is our own mind that likes to dwell in how I don’t fit in and how they don’t let me fit in. I wanted to go to one of the monasteries in the south and learn Tibetan and learn debate and I couldn’t do it. That’s a big thing to be discriminated against when you can’t get the kind of education you want. I am so sick of talking about making a deal, I have better things to do in my life now. Don’t get stuck in it.

Audience: Related to that, are the monks discriminated in Tibet? They are looking for enlightenment, and how do they justify that behavior?

VTC: I don’t know. I wish I understood it. It seems to me that many people… I don’t understand. I can’t explain why they think the way they think.

Audience: Cultural conditioning?

VTC: Yes, it’s cultural conditioning, but why don’t they question it? That’s the question, why don’t they question their cultural conditioning?

Audience: The point I wanted to make was slightly different actually. It was not about Tibetans, but it’s related because it’s this thing of the strength of the cultural conditioning. This conversation is really important in the Buddhist perspective of transcending the identity, but I’ve been having this kind of unease this morning and this afternoon. In having this conversation, I think it’s also important to acknowledge some of the positive aspects that are going on conventionally on a level of society. That we’re going through a transformation where we’re trying to emerge into a more diverse society that’s more tolerant and open. Then the whole identity issues that are emerging in discussions are related to that and so there are really positive things that are going on. I think when having the conversation, holding both. Even conventionally, of course, there’s the shadow sides of all the identities, but I think the positive aspect also has to be voiced and acknowledged.

Audience: Just look around in this room.

VTC: Do you want to explain?

Audience: I was just responding to what you said, and I would say just look around this room, it’s quite a diverse group. I’m really struck by it a lot of times. Right before that thing happened in Charlottesville, I’d written a letter. Sometimes I write a letter and send it to everybody that I know because I don’t write very often. I was looking around at the Abbey and we had people from so many different places here. Then actually, after the thing happened in Charlottesville I lost the heart to send it, but I think that we have to hold on, as you’re saying, just to that. I was thinking, when you talked about—I can’t remember her name right now, feeling invisible?

VTC: Oh, Marcia?

Audience: Yes, Marcia. I know her too. I really don’t think I could have understood that unless I had put on these robes and then gone to Emory to a Buddhist event. I just really got what you were talking about in my one little immersion of going from somebody who is a woman in the university doing well to putting on these robes and being in a Buddhist setting in the university. It was really strange, and I would have been better to have felt invisible because I wasn’t used to the interactions in that way. I was like, “Wow, I’m on the lowest on the totem pole here.” I never felt that way in a social setting like that before. I felt it in other ways, but I wasn’t quite expecting that. I feel like I’m at the women’s college here, you know how they say that women flourish in women’s colleges because they can do everything? In a sense, I feel that’s kind of what it’s like here. We can do everything. Then Venerable Wu Yin is taking pictures of us driving tractors because people thought they were using chainsaws. We just take care of the place and it’s no big deal, but to some people it’s like, “Wow, look at that.” For me, I have not paid much attention to this. I just don’t let it get in my way. I think I’m a little bit like one of my Vinaya masters felt about the Guru Dharmas. He was asked this question, my preceptor, and he just said, “We ignore it.” They don’t discuss it. They just go on. I think it’s because they found it too divisive. The conversations would only be divisive and not be harmonious. We have to work against the social injustices, but we can’t let things go to the place where we can’t even have civil conversations, where we can’t be harmonious in dialogue with people. If it can’t be harmonious, then what’s the point?

VTC: Oh my goodness. I think we need some meditation time. Let’s settle the mind a little bit. We all have a lot of ideas. We have a lot of perspectives. We all want to be heard. There isn’t time for everybody to be heard. You can blame me. Let’s come back and let’s do something together like recite the mantra together and hear the voice of all of us combined reciting the mantra. Then going into silence after that.

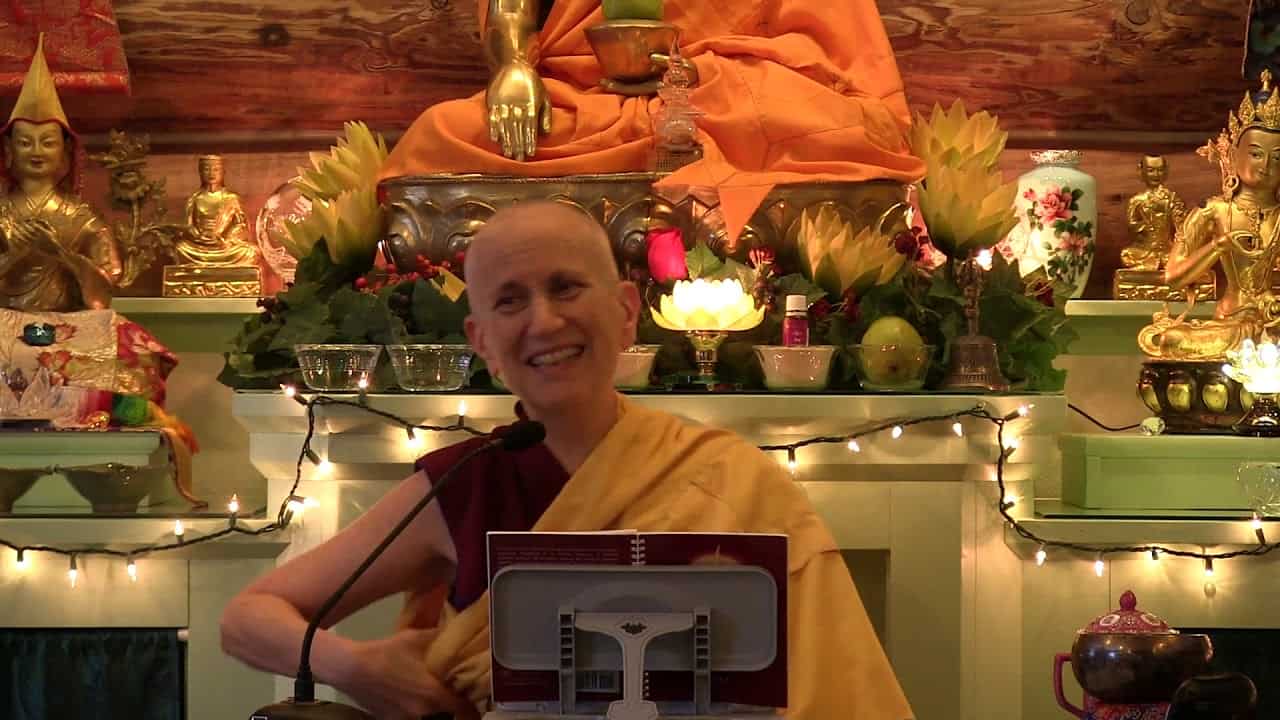

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.