Cultivating a bodhicitta motivation

01 Vajrasattva Retreat Cultivating a Bodhicitta Motivation

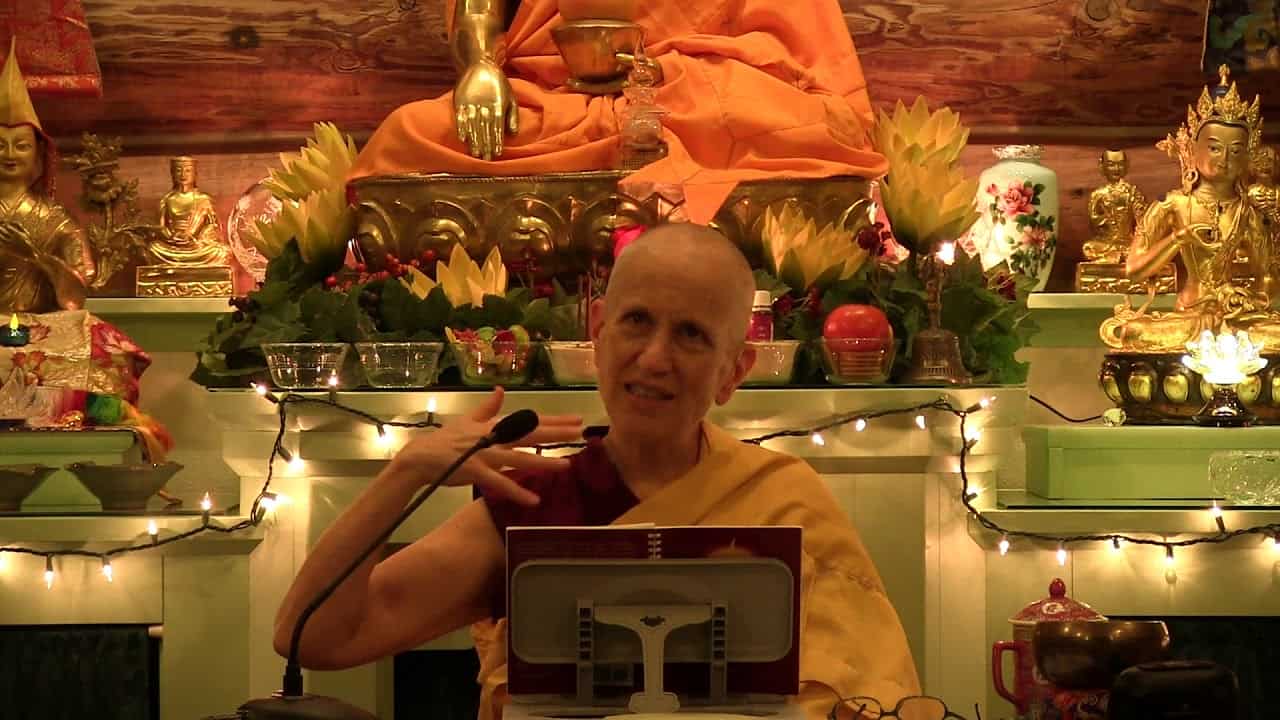

Part of a series of teachings given during the Vajrasattva New Year's Retreat at Sravasti Abbey at the end of 2018.

- The importance of motivation

- Bodhicitta

- Attachment to the happiness of only this life – the eight worldly concerns

- The disadvantages of samsara

- Visualizing Vajrasattva

- Vajrasattva represents our inner potential

- Making (new year’s) resolutions

- Removing obstacles to actualizing our goals

- Making realistic resolutions

- The power of regret

- Regret versus guilt

- Determining virtuous from non-virtuous actions

- Regret and rejoicing go together

- Questions and answers

- Separating our actions from who we are

Good morning everybody. We’ll start with some chanting and a little bit of silent meditation and setting your motivation, and then we’ll go into the talk.

Recall as we heard last night from His Holiness in approaching the Buddhist path that we are all interdependent and we all need each other to survive. It’s a simple statement but really contemplate the ramifications of that in your life. As you let that sink in, let arise a feeling of gratitude and affection for other living beings and, together with that, a very natural wish in your own heart to do something for them in return. Each of us has our own practical way of helping others in this life. That’s one way to express our gratitude and appreciation, and in the background or maybe in the forefront, to have the bodhicitta motivation for full awakening as the ultimate, long-lasting way of being of benefit to others. Generate that motivation as the reason why we are sharing the Dharma today, the reason why we are having the retreat, the reason we are alive.

Bodhicitta motivation

One of my very first Dharma teachers is famous when he gives a talk. If the talk is an hour and a half long, it usually winds up being three or four. The motivation is at least half of the talk, if not three-quarters of the talk. This was my first Buddhist training, the importance of the motivation. Again and again he hammered it into us, “What is your motivation?” [and] not just motivation in general, but the importance of the bodhicitta motivation.

As years have gone by, I’ve really appreciated the fact that he did that more and more. He would take maybe an hour and a half to set the motivation, so that included a teaching on the eight worldly concerns, on karma, on the disadvantages of samsara. He would pack everything—the entire lam rim—into the motivation, culminating with bodhicitta. Sometimes, being a newbie, I would sit there and go, “When’s he going to talk about the topic that he is supposed to talk about? And why is he always talking about bodhicitta?” As the years have gone by—it’s over 40 years now—I’ve really come to understand and appreciate that, because without the bodhicitta, it seems to me anyway, that my whole life would be meaningless. There wouldn’t really be any purpose to it. I really appreciate the fact that he repeated this again and again so that there would be no way for our minds to wiggle out of it. I saw over the years things that happened, how people would start out in a tradition speaking about bodhicitta and then move on to a tradition that didn’t speak about bodhicitta and that always puzzled me.

There was one person I knew who did a year-long shamatha retreat. She was, prior to that, planning to ordain here and then after the retreat she became a Theravada nun. It’s virtuous and wonderful that she ordained, but I always puzzled, “Wow! How can you do a one-year retreat and come out of it not having your bodhicitta be stronger?” Of course, maybe she didn’t have those instructions so much and that wasn’t emphasized a lot before the retreat. I know somebody else who did several years of shamatha retreat and after she came out, she decided to go back to school. Then she called me and asked if she could return her precept to abandon taking intoxicants, and I was shocked, “How could you do years of retreat and want to relinquish your precept to abandon intoxicants?” especially a shamatha retreat, where if you’re intoxicated, forget it. You’re not going to get any shamatha. Just observing these things, not judging these people, but just seeing how things play out in people’s lives. It really made me have much more gratitude for this early training I had.

Eight worldly concerns

Some other things that my teacher taught—[and] this all somehow relates to the Vajrasattva sadhana, so I’m not going off course. Maybe a little, but another thing that he did, when he finally got around to the topic of the talk, so often it was about the eight worldly concerns, working only for the happiness of this life. The people coming to Dharma in the 70s were very different from the people coming to Dharma today. We were all a bunch of—I guess you could call us hippies—who straggled our way up from freak street, which is where you got chocolate cake and dope, up to the Kopan monastery where you got Dharma. Our lives were very much involved in the eight worldly concerns, as are your lives, and all of society revolves around the eight worldly concerns. For those of you who aren’t familiar with these, they are four pair that all have to do with attachment to the happiness only of this life. Being delighted when we have material possessions, being upset when we don’t have them. Being so overjoyed when people praise us and approve of us and dejected when they don’t, when they disapprove and criticize us. Being over the top when we’re famous and have a good reputation and again feeling depressed when we don’t have that. Then the last pair is really loving pleasant sense experiences and seeking them out and then being upset when we don’t have pleasant sense experiences.

He would talk about these again and again, ad nauseum. He would call it the evil thought of the eight worldly concerns, and he would call it the evil thought because the more we are involved in these four pairs of attachment and anger or attachment and aversion, the less room there is in our mind to understand the Dharma. This is because we’re so distracted by external things that there’s no time to reflect internally. In addition, by being attached, by having all this attachment going on and aversion to external objects and people, we create a ton of negative karma. That actually impedes us on the path and sends us to a horrible rebirth. So here we were, this group of motley people. I couldn’t believe it, it’s not like the nice, well-dressed people who come to the Dharma today. We were really quite a motley group, and totally involved in the eight worldly concerns, and there he would sit in front of us every day trying to get it through our thick skulls to really look at our lives and see what was valuable.

Again, even though at the time it was so painful in some ways because it was like, “Everything I like I have attachment for” and then the confusion, “Does that mean I’m not supposed to have any pleasure?” No, it doesn’t mean that. The pleasure is not the problem, it’s the attachment. Then also seeing how much upset and anger I had when I didn’t get what I wanted, when things didn’t go my way, and how much I played that out in my life to the unhappiness of the people around me. So, it was painful to—shocking, maybe not so painful, shocking—to realize that about myself. I say this because I thought I was a pretty good person before that, but at the same time it was also a great relief because I began to see, “Okay, this is what the source of my problems is and this is what I have to work on. And if I work on it, I’ll get rid of the source of my problems.”

Disadvantages of samsara

The other thing he would talk about: bodhicitta. Evil thought of the eight worldly concerns, then the disadvantages of Samsara. At the Kopan one-month course, he would give the eight Mahayana precepts every day for the last two weeks. When you do the eight Mahayana precepts usually there’s a short motivation and then you kneel down, it’s a short verse you recite, and then the whole thing’s over. Well, the motivation was usually at least an hour long and he often waited to give the motivation until we were all kneeling. The Tibetan way of kneeling is very uncomfortable because it’s more like squatting, so we’re squatting and it’s so uncomfortable and he’s going on and on about the faults of Samsara. [He would do this] again and again to help us generate the bodhicitta motivation, because to have bodhicitta you have to see the faults of samsara. Then he would finally give the precepts, and we would all go, “Oh thank goodness.” It was kind of an ordeal. But again, this has really stuck with me over the years such that now, whenever I see my teacher I try and really thank him for that early training and how he so much put the important Dharma principles in our mind from the very get-go, and really, really appreciating that.

I see now how often people don’t get that kind of background and foundation, and instead they go right into tantra then get quite confused. They always say, “build a good foundation, then build the walls, then the roof,” so I’m a foundation person. Let’s have a good solid foundation in your Dharma practice because if you have that then you’re not going to get rattled in your life when things happen, and of course things will happen, guaranteed. We are in samsara, there is no way that we’re going to escape aging, sickness, and death. There’s no way to escape as long as we’re in samsara, to escape not getting what we want, and getting what we don’t want and being disillusioned even when we get what we want. There’s no way because that’s the nature of an ignorant mind. As long as we are in samsara we should expect that, and we need to learn how to deal with these situations so that our long-term goal of full awakening remains steady. We can progress on that path going there instead of in the middle saying, “This is just too hard, it’s too much, I just want to go and have a beer every night after work and forget about it.” We really need that strong foundation and long-term perspective to keep on going.

Motivation for the Vajrasattva practice

How does that relate to Vajrasattva? Because to do the Vajrasattva practice, the most important aspect of it is, “What is our motivation for doing it?” It’s not just, “I’m doing this practice and there’s this brilliant white deity on top of my head showering blissful energy, and I feel so blissful and I can’t wait to tell all my friends about it, and then they will know how spiritual I am and how I am having realizations right, left and, center even after a four-day retreat.” That’s not our motivation. That’s not why we’re here. I think one of my jobs is really reshaping whatever motivation we came here with, and we probably came here with a bunch of very different motivations. Some of us may not even know our motivation, it’s just on automatic, “It’s here, I go,” without really thinking, so all of this relates to the very beginning. If you look in the sadhana in the red book, we’ll follow this one for the weekend and then the longer one for the one-month retreat.

This first thing is visualizing Vajrasattva and then taking refuge and generating bodhicitta. This is the first of the four opponent powers for purification, refuge, and bodhicitta. Here, it comes at the beginning of the sadhana and to take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha, to generate bodhicitta. Then we have to have a mind that wants to free ourselves from attachment to the eight worldly concerns; a mind that wants to be free of samsara and all its limitations; a mind of bodhicitta that aspires for full awakening to benefit all beings. Even if at our level we are generating these kinds of attitudes, we’re fabricating them, or they’re contrived, because we have [to] think about them and say the words. Even though we say the words and we agree with the words, still deep in our heart we’re not quite there in believing it. But that’s okay, because it’s a step in the right direction. What do they say? Fake it until you make it. That’s what we are doing, we’re practicing generating those virtuous kinds of thoughts and simply by the practice and the force of familiarization, over time they will become our natural way of looking at things.

Manifestation of Vajrasattva

Now the Vajrasattva practice, the essence of it is the four opponent powers because Vajrasattva is a manifestation of the awakened mind of all the buddhas manifesting in that form in order to help us purify our negative karmas and reduce our attachments and so on. You can see by Vajrasattva’s form, he’s indicating that purification. His body is made of light. That already is loosening something up in us because we’re so attached to this body, which actually is just a bunch of vegetable goo. I know you don’t like me saying that, but the Buddha said it and I’m just repeating what the Buddha said. If you look what this body is, really, it’s nothing so fantastic. It’s our vehicle, it’s the basis of our precious human life. What Venerable Sangye Khadro was saying yesterday, it’s important, and among all the kind of bodies in samsara, it’s one that’s good, but over the long term this body is going to betray us. There’s Vajrasattva who’s going beyond having to take a body like this and has deliberately manifested in a body of light. His body’s light is radiating out light, purifying light. That’s something that’s quite important. He is sitting there and when you visualize Vajrasattva, I always like the eyes. There may be different parts of Vajrasattva that really resonate with you, but for me it’s the eyes because his eyes are so peaceful, so incredibly grounded and peaceful and not wanting or needing anything. To me that reminds me, “This is the direction I want to go in,” a direction of not wanting and needing and craving and seeking and clinging and fighting with the external world to get what I want.

What I really want to develop inside myself is some equanimity, some contentment, some satisfaction that doesn’t depend on having the things I like around me. Wouldn’t that be nice? Think about it in your life. Wouldn’t it be nice to be able to be peaceful and content no matter whether you were in a prison or on the beach or with the person you hate the most or the person you love the most? Wouldn’t it be nice [to] just have some even-mindedness without being an emotional yo-yo all the time? Up and down and up and down, I like, I don’t like, give me this, get that away from me. Vajrasattva’s eyes and the deep peace there really express that to me, just that thing of when you’re enlightened, you are totally satisfied. Wow. Wouldn’t that be nice? Because what’s our culture here? Constant dissatisfaction, fueled by advertising, publicity, social media, everything. We want more, we want better. Here, Vajrasattva‘s satisfied. He’s holding a dorje and a bell. The Dorje is representing compassion or great bliss. The bell is representing the profound wisdom that knows the nature of reality. He’s sitting in the vajra position, which is a bit difficult to sit in. How many of you are sitting in it right now? Even when we meditate it’s hard to sit in it. It’s a very stable position, it’s a stable position. The whole way he looks; he has ornaments, but his ornaments are the six or the ten perfections, they aren’t like the ornaments we have, which are designed to make us look better because we don’t feel good about ourselves or look better so we can impress other people and get them to be attracted to us. Vajrasattva’s ornaments are these virtuous qualities, the practices of bodhisattvas. That is expressed to us in his physical form. Like I said, he’s a manifestation of all the Buddhas’ omniscient minds. Don’t think of Vajrasattva so much as a person. He looks like a person but there are many beings who become enlightened in the aspect of Vajrasattva. It’s not just that there’s one Vajrasattva. When you become enlightened you can manifest in many, many different forms. In a way, Vajrasattva is representing what we want to become, the qualities we want to develop. We’re visualizing Vajrasattva on top of our heads like he is an extension of our self. To put it in new age language, maybe you could say our higher self, higher than our self. I don’t like new age language much but it’s the idea that we’re seeing our own potential, combining that with the attainments of those who have already gained awakening, and then visualizing that on top of our heads and then relating to the Vajrasattva that we are visualizing.

The power of regret

How are we going to relate to the Vajrasattva that we are visualizing? Specifically, by asking him to help us purify our negativities. We do Vajrasattva retreat at the abbey over New Year’s because New Year’s is a time when people make New Year’s resolutions, which I’ve never really believed in. In Buddhism we make resolutions every day, we don’t wait until the new year to make a resolution, and most of our New Year’s resolutions don’t work out. Has that been your experience? You make really strong New Year’s resolutions and they last maybe a week and then that’s kind of it. In thinking about it, why don’t our New Year’s resolutions last? I think it’s because we haven’t created the cause for them to last. We lack the foundation so we’re making these resolutions, but we haven’t dealt with all factors that inhibit us from actualizing those resolutions. What are those factors that inhibit us? They are usually our past actions and our past attitudes and past emotions. We’re not working on ourselves to clear away the obstacles so then the New Year’s resolutions don’t come to fruition. That’s why purification is really important, because it helps us clear away these obstacles. That’s why I think this kind of retreat is very well suited for New Years’ time, which is when people do this kind of thing. We’re going to spend the time of really looking at the obstacles that we have to becoming the kind of person we want to become and being able to actualize the resolutions that we’ve made. We’re also going to look at the resolutions we’ve made and see if they are practical or to reassess our resolutions.

The retreat isn’t just about looking over our past and going, “Well, I messed up here and I messed up there and I messed up there and there and there.” It’s also about learning to see our potential, rejoicing at our good qualities. If you look in the seven-limb prayer, the third limb is confession and the fourth is rejoicing. These two go together. We’ve got to acknowledge our mistakes and we’ve got to rejoice at our successes and our good qualities. We have to learn how to acknowledge our mistakes in a healthy way and how to rejoice in our good qualities as well as the good qualities of others in a healthy way. Right now, I’m not sure we know how to do those things in a really productive manner. Sometimes we get kind of messed, up so we’re going to be looking a lot at that in the retreat. One example is one of the four opponent powers, the first one actually, which is regret. If we want to purify our misdeeds, the first thing we have to do is acknowledge them and have regret. Now, how is it that sometimes we don’t know how to regret in a healthy way? This is because instead of feeling regret, we feel guilt. Instead of regret, we blame ourselves and then we get tangled up in guilt, and self-blame, self-hatred, shame, and all those other yucky kinds of things. Anybody have problems with those? I think most of us do, all of us do. In thinking about it—because I’ve taught this many times—I keep thinking about, “What does it mean?” I think with regret, first of all we’re just acknowledging it and we have a feeling of sorrow; sorrow that we went beyond our own ethical standards, sorrow in the sense that we disappointed ourselves, sorrow in knowing that we caused pain to others. Now, there’s nothing wrong with sorrow, there’s nothing wrong with regret, but we often twist them. It’s not the words so much [that] we say to ourselves, as how we say the words and what the implications are.

Let me give you an example. I spoke harshly to somebody, let’s say. I feel really sorry because in my ethical standards I would like to speak to people in a kind way and not be somebody who propagates dissention and discord and hurt feelings. I disappointed myself in that I didn’t fulfill my own standards and there’s a sense of sorrow for that and also seeing the result, what I caused other people. Do you see the tone of voice that I’m saying that in? It’s just a tone of voice where I acknowledge what happened and there’s sincere sorrow or regret. Then you can also say those words, “Oh! I have such sorrow that I went against my own ethical principles. Oh! I hurt these people’s feelings!” Same words, [but the] meaning is different, isn’t it? The second one, the implication is, “Oh, I feel so sorry I went against my ethical principles,” implying what a bad person I am. “I’m so sorry, again I hurt people’s feelings.” Implication: I can’t do anything right, I’m a disaster. Same words but the implication, the way we’re saying them to ourselves gives us an entirely different feeling. It’s really, really important in the retreat when you are reflecting on past deeds to make sure that there’s that even, accepting tone of voice, not an angry, “You’re a jerk” tone of voice that we are directing to ourselves. Is this clear?

This is super important because if we are misconstruing what regret means then the other three of the four opponent powers are also going to be misconstrued. It is really important to understand what regret is. I always like to show the difference between regret and guilt with an example of an electric stove. You can turn off an electric stove [and] the burner is no longer red, but it’s hot. If you touch that burner and you burn yourself, do you feel guilty? No. Do you regret it? You bet. Do you see the difference between them? I touched that hot burner, “Whoa, I regret doing that.” Not, I touched the hot burner, “Oh, what a bad person I am. What a disaster I am. I bummed up again,” and all the drama that follows that. Make sure when you’re looking over your past actions that you really have that sense of regret and you can regret your negativities because you have confidence in yourself. A person who has confidence can be humble. A person who has confidence can own their mistakes. A person who is arrogant can’t own their mistakes, can’t be humble. They just go through life stepping on toes right, left, and center. Really spend some time thinking about this, [it’s] quite important.

With the power of regret, which we come to on the first page, since it’s actually one of the main things, the most important of the four opponent powers, I want to spend some time on it. When you look over your past and your regrets, it may not always be clear to you if some actions you did were virtuous or not, non-virtuous or not. I know for me, sometimes it takes me years to look back and actually figure out what my motivation for something was at the time. In general, if I feel uneasy about something I’ve done, then there is probably some element of affliction involved in my motivation. Many of our actions we start out doing what we think is something good but at the end we feel uneasy about it. These kinds of situations can be difficult to decipher. An example: you have a very good friend who is going down the slippery slope getting involved in something that you know is not going to wind up good for them, so you go to your friend and you point that out to your friend and your friend gets really upset with you. [Have] you ever had that happen? With a good motivation you’ve gone and said something to somebody and then they get mad at you? Then self-doubt arises, “Oh, maybe I did the wrong thing, maybe I shouldn’t have said anything. But if I didn’t say anything and they continued to slide down that slippery slope, I wouldn’t feel right about myself either.” As a real friend to somebody, I should be able to speak honestly to them, so we get confused about that action. What we need to do in that case is really come back, “What was my motivation?” If we look and our motivation really sincerely was to help that person because we care about them and we see that maybe they are getting involved in a bad relationship or they’re getting involved in a murky business deal or they’re starting up their substance abuse problem again, whatever it is, but really out of kindness I spoke to that person with sincere help, then fine. Don’t berate yourself for that. That part of it was quite virtuous. When you start doubting it afterwards because your friend got mad at you, what’s going on in your mind at that time? Eight worldly concerns. Praise. Approval. We’re involved with attachment to praise and approval and that’s what is making us doubt the virtue of our initial intention. When we can look at it like that and say, “Oh, that’s just my attachment to praise and approval.” Not just say, “Oh, it’s attachment to praise and approval, I shouldn’t have it,” that’s not going to get rid of the problem. This is what I mean by creating the causes to hold our New Year’s resolutions. Let’s look at what are the disadvantages of attachment to praise and approval. What are some of the benefits of praise and approval from a Dharma perspective?

Audience: If you get praise from your teacher for things that you do, at least you know you are going in the right direction.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Okay, that’s true, but this situation was regarding a friend.

Audience: Can you say your own children?

VTC: You mean if your children like you that means what you do is right? No.

Audience: That’s not what I meant.

VTC: Let me ask you, because we’re attached to praise and approval, does receiving praise and approval make you healthier? [Audience: No.] Does it extend your life span? [Audience: No.] Does it get you a good rebirth in the next life? [Audience: No.] Does it help you progress along the spiritual path? [Audience: Maybe the new age path.]

VTC: When we really look, do praise and approval really do anything for the things that are most important to us?

Audience: I have a question. Is praise and approval the same thing as receiving, say, positive feedback on something you did beneficial along your path? If I am asking you, “Am I doing this properly?” and you say, “Oh yes, that’s the way,” is that the same as praise and approval?

VTC: No. Just asking feedback like, “This was my assignment, did I do it up to par or up to the expectation?” You’re asking for practical feedback on something. That asking for practical feedback, “Yes, you put the columns and rows in the right place,” that’s very different than seeking praise and approval, which is people telling you what a good person you are. Not only did you put the rows and columns in the spreadsheet correctly, but you are a wonderful person for doing it.

Audience: Thank you.

VTC: Now, one person said [that] one advantage of praise and approval is you gain confidence. I wonder. I wonder because I’ve had experiences where two people have given me feedback on the same action, one person praised me for it the other person criticized me for it. If I rely on other people telling me I’m good or bad in order to have confidence, in this kind of situation I’m going to get very confused. This is because I’m not going to know who I am because I’m giving my power to other people to tell me who I am instead of learning to assess my own actions myself. Then this person praises me, “Wow, I’m fantastic, look how good I am,” then the next person criticizes me, “Oh, I’m a failure.” This is where we get this emotional up and down, up and down. It’s a thing, I think. What’s important is to learn to evaluate ourselves. Sometimes we may ask people for feedback, but we need to make sure the people we ask for feedback are wise people. If we just ask our friends who we know are going to say nice things about us for feedback, we may be limiting our scope of self-knowledge, because why are you a friend? It’s because you say nice things about me. If you stop saying nice things about me, you may not be my friend anymore. We have to, when we look for feedback, really look for the feedback of the wise, not the people who always think that we’re wonderful because they are attached to us.

Audience: When you were talking about the relationship between praise and confidence and you were talking about it in terms of a dependence, where our confidence is dependent on the praise we get, that’s the—how to describe it—the toxic element. I think there is a healthy relationship that one can have with praise in relationship to confidence if there’s not a dependence, where—being able to acknowledge and accept when people reflect back good things that we’ve done and use that as a way to rejoice, and also rejoicing in the other person being able to see that and say that about us—where it can be healthy. I’ve certainly seen in Dharma communities many people seem to have developed this kind of inability to hear and accept when a complement is being made and that too seems there is an aspect of that that also seems dysfunctional.

VTC: This is the difference, receiving praise and being attached to praise. It’s the attachment to the praise that is the trap because that makes us dependent on hearing nice words from other people to believe in ourselves. If we aren’t attached to the praise, then it’s nice to have feedback from other people. I really liked what you said about rejoicing in the other person’s happiness and virtuous state of mind. Even when people praise, I always recognize, yes, they praise and I’m glad they’re happy, but I ‘m not going to latch onto that and think that that’s really who I am and I don’t need to do any more work in that area. If I latch onto it, then that’s going to be my downfall. I am going to get arrogant. Regarding the inability of some people in centers to receive positive feedback or receive praise, I think sometimes that is based on, and this might be a good topic for discussion group, it might be based on the feeling, “If somebody praises me then I am obliged to them. I have an obligation to them.” It’s like if somebody is generous to me, now I owe them something. Sometimes we get hooked in that. Or somebody praises me [but] actually I know my own inner world a bit better and I know that, “Okay, I may have that quality but I have so many negative qualities and I am looking at all my negative qualities and there’s really no space to acknowledge that positive one.” That’s our problem, our lack of self-esteem. That’s why I said that regret and rejoicing go hand in hand. We have to be able to look and rejoice at our own virtue, rejoice at what we’ve done well, but without latching onto it and making it a personal identity. When I first started giving dharma talks—which I never had in mind to do but my teacher pushed me to do and I couldn’t get out of it—when people would sometimes say, “Thank you, I really benefitted from that,” I would always go, “No, no, no.” Like you said, I can’t accept that praise. Then I asked one of my old Dharma friends and I said, “What do you do when people praise you after you give a talk?” and he said, “You say thank you.” Duh! Of course you say thank you, and that ends it. If I say, “No, no, no, I don’t deserve it,” then the other person feels like I’ve rejected what they are saying as if I’m calling them a liar. Then they say it again and I say no again and there is not a very good feeling, whereas if somebody says something nice and I say thank you, I’ve acknowledged their gift of praise and we go on.

Other questions about this so far?

Audience: I wanted to ask you to clarify about this disappointment. Like you said, when you do something wrong—so when you were talking about this healthy sense of regret—there is a disappointment of having done such a thing. How [do you] balance between being disappointed about an action and being disappointed in oneself, the latter which seems definitely to be a rejection of oneself, which seems to be a negativity?

VTC: We have to separate our actions from who we are. This is one of our big problems, with our self and with other people. We think we are our actions. If I am disappointed in my action, then I’m disappointed in myself because I am a rotten person. If I look at another person who’s acted in an abominable way, if I don’t like their action, that means they’re an evil person. We confuse the action and the person. Here, with regret and also in terms of our relationships with other people, separate it. I am disappointed in my action, but I know that I have other qualities and in the future I can do differently. It’s not that I’m bereft of all good qualities. I messed up in this one instance, but let’s give ourselves some credit, I have some good qualities, I have some knowledge, I can contribute. That action wasn’t good, but that doesn’t mean that as a person that we’re shameful and worthless and stupid. This is really important. We have to really understand what it means to have Buddha nature and understand that we have that kind of potential, and that it’s never going to go away no matter how we act.

In these early courses I was telling you about at Kopan, when Lama Yeshe would teach, he would be talking about bodhicitta and the question would come up, “What about Adolf Hitler? What about Joeseph Stalin? What about Mao Tse Tung?” And Lama would say, much to the shock of all of us, “They mean well, dear.” Hitler means well? “They means well dear.” Huh? You get fed these koans by your Tibetan teachers—the Zennies think they have the corner on koans, but they don’t. Hitler means well. Then you think about it, in his corrupted ignorant state of mind, he thought what he was doing was good. If he wasn’t in that state of mind, if he had any wisdom about cause and effect, if he had any compassion, if he had those other things that he has in his mindstream in seeds… They certainly were not fully developed or even partially developed during his lifetime, but those seeds are still there. He meant well, but of course what he was doing was completely ignorant and abominable. Even Hitler had the Buddha nature and even Hitler was capable of kindness. Lama would remind us, he was nice to his family. You think, “Wow, this guy was nice to his family?” Well yeah, he probably was.

It’s this thing of being able to encompass that sentient beings are not good and bad. Actions are virtuous and non-virtuous. Sentient beings all have the potential to become fully awakened. We have to see that and that includes us. That’s why instead of saying, “Look at what a failure I am, look at how I’ve messed up, blah, blah, I’m worthless,” it’s, “No. I have the Buddha potential. Those factors are in my mind right now. They’re seeds, I need to water them, and I can water them. I need to put myself in a good situation where I get support for developing those aspects of myself that I want to develop and stop putting myself in a situation where the parts of me that I don’t like get developed.” I have that potential and it’s not going away, so let’s use it. Having that as the basis for our self-confidence, because if we have that as a basis then our self-confidence is going to be steady. If we think that others’ praise, if that’s the basis for our self-confidence, then when somebody criticizes us, we’re flat. If we think our youth and our artistic ability or our intellect or our athletic ability or any of those things are the basis for our self-confidence, we are not going to be able to uphold that either.

We’re getting older and we’re going to lose those abilities and we might even get senile. Some of you may have the experience, I’ve had this experience many times. I’m thinking of one person in particular right now who is a professor of geology in Montana—brilliant man, very kind man—and boy, he got Parkinson’s, he got senile. It was amazing to see him change from what his intellect was to what it became. We have to look at the things we use as the basis for our self-esteem. We’re not always going to have those things in this life, whereas if we develop a kind heart, that is something that you still have even if you get dementia. My friend—this one Dharma friend, Alex Berzin, I refer to him a lot—was telling me that his mother got completely senile. She was putting on seven pairs of pants; instead of lipstick she would put on toothpaste; instead of toothpaste she would put lipstick on her toothbrush. But whenever he brought her some cookies or candies, she would take them around and give them to all the old folks in the old folks’ home, and he said this was her quality throughout her whole life of loving to be generous and sharing with other people, and that quality came through even when she suffered from dementia. We have to see, what is it? Where are we putting our marbles? No. Where are we putting our eggs? I don’t know. Is it eggs or marbles? You take your marbles and go home. You put your eggs in a basket. You lose your marbles. I think you get the idea. We are going to end the session for now and then continue this afternoon.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.