Practicing the Dharma with bodhicitta

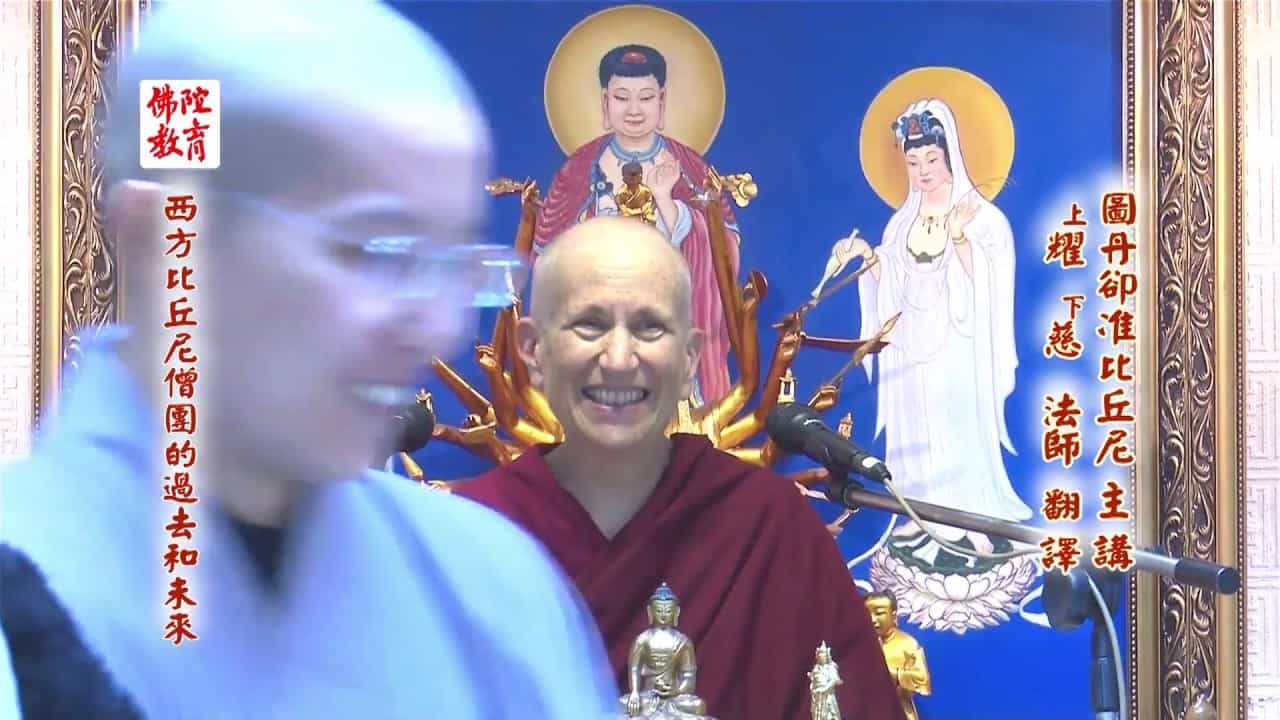

A talk given at the Luminary Mountain Temple in Taipei, Taiwan (ROC). In English with Chinese translation.

- Bodhicitta as the motivation for practice

- The three levels of motivation

- Reflecting on the kindess of others to cultivate bodhicitta

- The two aspects of the path to practice—merit and wisdom

- Questions and answers

- What practices allow us to cultivate merit and wisdom simultaneously?

- Are we actually benefiting sentient beings when we generate bodhiccitta?

- If we have limited resources, can we still generate bodhicitta?

Bodhicitta and meditation (download)

It’s a great privilege and honor for me to be here to talk to you. I thought tonight to talk a little bit about bodhichitta: how it relates to our meditation practice and everything we do in our Dharma practice. Bodhichitta is the aspiration to attain full awakening in order to best benefit all sentient beings. They say that this is like the cream of the Dharma. In other words, when you churn milk, you get butter. When you churn Dharma to get the real good stuff, the rich stuff, then you get bodhicitta. Some people think that having bodhicitta means that you do a lot of social work and you are always very busy serving sentient beings in an active way daily. The social work is one manifestation of our intention to become awakened, but it’s not the only thing. Bodhicitta is the motivation that we want to have when we do anything in our lives. For example, when we’re doing our chores and we recite gathas that are related to bodhicitta and benefiting sentient beings, yet the action we’re doing is maybe sweeping the floor, washing the dishes, or something like that.

Bodhicitta is also the motivation for our meditation practice because if we really, sincerely want to become buddhas to benefit sentient beings most effectively, then we have to transform our own mind, we have to free our own mind from ignorance. How do we free our mind from ignorance? We do meditations such as mindfulness of the breath, the four establishment of mindfulness, serenity or shamatha, insight or vipashyana. Different Buddhist traditions may have different ways of doing these meditations, but that’s the technical way of doing the meditation. The motivation behind doing these meditations, for us as Mahayana practitioners, would be bodhicitta.

Now somebody’s going to say, “But mindfulness of the breath is a Theravada practice and they don’t have bodhicitta.” Actually, there’s two things wrong with that statement. First of all, the meditations, the mindfulness of the breath, the four establishments of mindfulness, shamatha, vipashyana, all of these are found in the Mahayana scriptures as well and they are taught in the Mahayana tradition. The second thing is that the Theravada tradition does have a lineage of teachings on the bodhisattva practice. This is something many people don’t know, but Acharya Dhammapala, who lived in the sixth century, compiled a lot of information from Pali scriptures. I wonder if he read some of the Sanskrit scriptures as well. I don’t know, but maybe. He wrote a whole text called the Treatise on the Paramis to explain the bodhisattva practice and he’s from the Theravada tradition. My point is that we shouldn’t get confused thinking that we practice with bodhicitta but we’re doing a Theravada practice because there is no problem, there’s no conflict in that at all.

One of the books that I had the privilege of co-authoring with His Holiness the Dalai Lama, was entitled Buddhism: One Teacher, Many Traditions, which is published in Taiwan with another title. In the process of researching and then writing that book, I learned so much about both the Pali tradition and the Sanskrit tradition and how they really come together in so many ways.

Why is it important that you generate bodhicitta before you do your meditation sessions? It’s because our motivation, I’m sure you know this already, is the most important component of whatever action we do and it is our motivation that determines whether an action is virtuous or not. If we just sit down to meditate without generating any motivation, then we have to ask ourselves, “Well, why am I doing this?” Am I coming to the session simply because the bell rang? Am I coming to the session so that my teacher doesn’t get upset with me? Am I coming to the session in order to create some good karma so I will have a good future rebirth? Now that’s considered a Dharma motivation, a virtuous motivation, but it’s also a small one because it concerns just ourself and just our next life. When you think about it, a good rebirth is good, but we’ve been taking one rebirth after another in samsara and it hasn’t gotten us anywhere. It’s like riding on a roller coaster. Have you ever been on a roller coaster – up, down, higher realms, lower realms.

At some point, we say, “I’m tired of samsaric rebirth. There’s nothing good about it at all and I want to attain liberation from samsara.” This is the motivation of the hearers or sravakas, and the pratyekabuddhas or solitary realizers. That’s definitely a Dharma motivation and a virtuous motivation. Actions we do with the motivation to attain liberation will result in our own liberation. But when we think of it, and we think of all the kindness that we have received from other living beings, does it feel right just to work for our own liberation and say, “Good luck everybody. I hope you get there but I’m going by myself”? When we really think that all living beings have been our parents in one lifetime or another, that they have been kind to us as our parents, then it would seem very ungrateful to just work for our own liberation and forget about everybody else. When we also really think that everything we have in this life is due to the kindness of other living beings, then it becomes impossible to ignore everybody else and work for our own spiritual liberation.

I remember one time my teacher talking about this. He was explaining, from his own experience, how grateful he felt to other living beings for the food he ate. At that time, he was a meditator in the Himalayas up near Namche Bazaar and the main food there was potatoes. Potatoes for breakfast, potatoes for lunch, potatoes for medicine meal, potatoes for snacks. Because he was a meditator, people in the village who were quite poor but they grew the potatoes, they would bring potatoes to him and offer them to him. He said that when he really thought about the lives of these people who offered him potatoes: how hard they worked the fields, how much suffering they went through in the cold to do manual labor outside, and just everything, even carrying the potatoes from their fields to where he was. He said that when somebody came and gave him just one small potato, inside that potato was so much energy from so many sentient beings that he said it was difficult for him to even eat the potato. He felt so connected with all these other living beings that he had to make their offering something meaningful.

How do we make the offering of one little potato, which embodies so many sentient beings’ toil, into something meaningful? Do we just cook the potato and then go on? Do we just take the potato and think, “Thank you for offering me this potato, but I have eaten so many potatoes in the last few years, I’m really sick of them. This potato is kind of old anyway.” He said the way he could make their offering meaningful was by eating the potato with the bodhicitta motivation. Bodhichitta, aspiring for awakening to benefit each and every living being, is so virtuous because it’s the highest aspiration and it concerns each and every living being, omitting none of them. If you eat a potato or if you do your meditation practice with bodhicitta, the merit you create is multiplied bazillions of times and it becomes very powerful merit because you are motivated towards the most noble goal of Dharma practice, and because you are working for the benefit of limitless living beings. If you really understand bodhicitta well, you see eating potatoes can be very meritorious. Even more meritorious is doing our meditation practice motivated by bodhicitta.

Some people think, “That sounds nice, but why should I work for all sentient beings? Some of these sentient beings are such jerks. They do so many harmful things. They start wars, they kill each other. Why should I work for their benefit?” Do you have some sentient beings that you just can’t stand? That person hurt me so bad, I will never forgive them! We are among friends, we can admit it. We have all had those kinds of thoughts from time to time. One way I have found to deal with those thoughts and to oppose them is to remember that even that person I can’t stand has also been kind to me. Everybody works at some kind of job doing something that keeps society functioning and because society functions, I have food and clothing and medicine, I was able to go to school, I have shelter. Anything I know came because other living beings taught me. I enjoy staying here with electricity but I don’t even know the people who made the electricity possible in this room. It could have been the person that I can’t endure, that I think is the chief jerk. When we look at it, people may have harmed us but actually the help they have given us in all our samsaric rebirths is just tremendous. It far outweighs any harm we have received. This is important to remember. We cannot stay alive without the help of others so everybody has been kind to us.

Somebody’s going to say, “Maybe it’s worthwhile working for sentient beings. But, all these aspirations, these unshakable resolves, these vows that the bodhisattvas make, they are totally unrealistic.” When my teacher guides us in generating bodhicitta, he says, “You’ve got to think, I’m going to do this action for the benefit of each and every sentient being and lead them all to full awakening by myself alone.” And when he said that, I thought, “I’m going to lead all sentient beings to awakening by myself alone? Can’t I have some help? I can’t lead all sentient beings to awaken. Anyway there are innumerable buddhas already. They should help me.” It’s not unrealistic to generate that kind of aspiration. It doesn’t matter whether we can actualize that aspiration or not but just the power of generating it means that when we have an opportunity to benefit somebody we won’t hesitate. And when bodhisattvas say “I’m going to go to the hell realm and lead every single being out of the hell realm,” you think, “That’s a bit unrealistic.” But it doesn’t matter whether it’s realistic or not. It’s beneficial to generate that aspiration. Because if we keep generating that aspiration then when we encounter somebody who needs some help, again we won’t hesitate. It doesn’t matter what Dharma practice we’re doing, we should do it motivated by bodhicitta and we should never give up our bodhicitta at any cost. Bodhicitta is really precious and we are so fortunate to have encountered the teachers who teach it.

If we want to become Buddhas, then we need to completely purify our mindstream of the afflictive obscurations and then also all of the subtle obscurations. So there’s two aspects of the path that we need to practice. One is the method aspect of the path. The other is the wisdom aspect. It’s said just as a bird needs two wings to fly, a Dharma practitioner who wants to go to full awakening needs both method and wisdom. So the wisdom aspect of the path is what helps us understand emptiness, selflessness, to overcome ignorance. So when you are doing, for example, a vipashyana practice, or you’re meditating on the four aspects of mindfulness, your aim there is to develop wisdom understanding those four objects, the body, feelings, mind and phenomena. We have to understand their ultimate nature, how they actually exist. By doing that, we fulfill what’s called the collection of wisdom. The collection of wisdom is the primary cause for the Buddha’s mind. So that’s one wing of the path, the wisdom side.

The other wing is the method side and this is where our motivation is so important. We can do an action motivated for good rebirth. We can do the same action but with the motivation of renunciation, wanting to be free of samsara. Or we could do the exact same action with the motivation of bodhicitta, wanting to attain full awakening for the benefit of all beings. The action is the same but three different motivations are Dharma motivations. The method aspect of the path for us, as people who want to become bodhisattvas, who are following the Mahayana path, then the method aspect of the path is doing everything motivated by bodhicitta. That’s where the other paramitas come in, practicing generosity, ethical conduct, fortitude or patience. The social work we do to benefit sentient beings directly in this life is part of that method aspect of the path. Through the method aspect of the path, then we fulfill the collection of merit. The collection of merit is the primary cause for Buddha’s form body. Do you see these parallels that keep coming?

We have, for example on the method side, acting in the conventional world and on the wisdom side, developing understanding the ultimate truth. On the method side, we do a lot of virtuous actions and we fulfill the collection of merit. On the wisdom side, we meditate on selflessness and emptiness, the ultimate nature of phenomena, and fulfill the collection of wisdom. On the method side, that becomes the primary cause for the Buddha’s form bodies, the rupakaya and on the wisdom side, that practice becomes the chief practice for the Buddha’s mind, the dharmakaya. Do you see how all these things fit together? Or are you going, “What in the world is she talking about?”

[Conversation in Chinese about translation terms]

Venerable Damcho: I’m understanding the terms she’s choosing as closer to skillful means. Not everything on the method side is skillful means necessarily.

Venerable Thubten Chodron [VTC]: But it does come close. Other questions. Please ask whatever you like.

Audience: So what is a method we can practice that simultaneously allows us to cultivate merit and wisdom, The method and wisdom side of the path?

VTC: To do them both together, before you do your meditation on emptiness and selflessness, you generate bodhicitta. Why are you meditating on emptiness and selflessness and the four establishments of mindfulness? So that you can become a buddha for the benefit of all beings. That is one way to combine method and wisdom so you are doing both at the same time. Another way is whenever you’re doing your daily activities or your social work, you do it with a bodhicitta motivation but you remember that every element in that action is empty of inherent existence and yet exists nominally. So let’s say you are teaching a class to the lay people. You generate bodhicitta as your motivation before teaching the class. At the conclusion of the class, you meditate a little bit on emptiness and selflessness. By thinking that what we call “the circle of three,” that there are three things in our action that exist dependent on one another and that means that they are empty of inherent existence. For example, those three elements, let’s say you just taught a class. So yourself as the person who taught the class. You are empty of inherent existence. There is no big I like, “I taught a class.” Instead, what we call ‘I’ is something that arises dependently on a body, a mind, all of our conditioning and experiences. When you are doing this, then you are bringing in the wisdom side of the path. ‘I’ as the one doing it am empty and exist dependently. The people that I am teaching are also empty of inherent existence but exist dependently. The third, the action of teaching the class, the action of their learning, is also something that exists dependent on many elements and so is empty of inherent existence. That was a good question.

Other questions.

Audience: In our practice of generating bodhicitta. For example, if we are just eating potatoes and generating bodhicitta in that way but we are not actually directly benefiting sentient beings. Are we actually benefiting sentient beings or do we have to wait until we achieve certain attainments, then we are able to genuinely benefit others.

VTC: Clearly a buddha can benefit others more than anyone else, which is why we all strive to be a buddha. Before becoming a buddha, yes our actions can benefit others. Eating a potato with bodhicitta is very different than eating the potato with attachment. At the end, the potato is in your stomach, that’s the same both ways. But if the potato got into your stomach motivated by attachment, then you have created negative karma. The mind of attachment is very small and very narrow. “Oh look, somebody gave me a potato, that’s because I’m important. They gave me the potato. I have the most beautiful potato and it’s all mine and I’m not going to share it with you. This is my potato.” Then you eat the potato, the whole time going, “Yum, what a delicious potato. I’m enjoying it. All those poor people who don’t have potatoes are not as lucky as me. Poor guys. Yum yum yum.”

Whereas if you eat a potato with bodhicitta and recite the five contemplations that we do before we eat a meal. Remember them? You recite them every day, right? The first four are helping us purify our motivation and the last one, I accept and eat this food in order to attain full awakening, that’s the bodhicitta motivation. If you eat the potato with bodhicitta, you are aware of the kindness of sentient beings, you want to repay that kindness, you are developing the courage to practice the bodhisattva path. But then somebody’s going to say, “It’s still you just eating that potato. How does that benefit all sentient beings?” Because of the bodhicitta motivation, your action of eating the potato is so virtuous. You are doing it to keep your own body alive so that you can practice the Dharma. By practicing the Dharma you can have the wisdom, compassion, and skillful means to best benefit sentient beings. Your whole reason for eating a potato is you’re steering yourself towards buddhahood and that is incredibly beneficial.

You may not be directly benefiting sentient beings now but what you are doing is you are accumulating the merit to become a buddha. When you are a buddha, you can benefit sentient beings in the most excellent way. Even before that, when you are a bodhisattva, you can extend incredible benefit to sentient beings. And then after you have eaten your potato with bodhicitta, you have that thought of, “I ate it to sustain my life so I can benefit others.” Then, whatever action you can do to benefit somebody, you do with a very happy mind. Does that make some sense to you? Remember, to become a bodhisattva, later to become a buddha, we need to accumulate so many causes. If we can make even small actions we do very powerful through the bodhicitta motivation, then that really helps us accumulate the causes for buddhahood very quickly. I bet your health is going to be better if you eat the potato with bodhicitta rather than eating it with attachment.

Audience: In order to benefit sentient beings, we need all kinds of resources, whether it’s material, or in terms of human resources. How do we, in a situation of limited resources, still generate and act with bodhicitta? To give an example, maybe I am working on a project and I don’t have enough volunteers while another team has many volunteers, what do I do? Or maybe I have many volunteers and they don’t, do I give away my volunteers? How do I work in a situation of limited resources with bodhicitta?

VTC: We can see in a situation of limited resources how easily our self-centered mind comes up. “I’m doing this project, this project is the most important one in the entire monastery. And this other department, they have more volunteers than I do, that’s not fair!” And, “I even ask people to do things, they don’t even do it right, they leave it all for me to do.” That can happen, can’t it? How you transform that with bodhicitta is, first of all you think, “If I have limited resources, that has something to do with my karma.” Maybe in the past, I was a lazy volunteer. Who? Me? I’m always the best one. Well, maybe once in a while in a previous life I could have been a bad volunteer and just been totally unreliable. What’s happening to me is exactly what I did to others. There is nothing to complain about. If I don’t like the results, I had better stop creating the cause.

In the future I had better be a very enthusiastic volunteer and help others. Instead of being jealous of the other departments who have more volunteers and the “good” volunteers, rejoice. It’s wonderful that they can work on their projects in a good way and they have the resources. I’m really happy because whatever they are doing is benefiting everybody. So I don’t have all the resources, I may have to work a little bit harder, I may have to work a little bit longer. But this is part of my training to become a bodhisattva. If I can do this work with a happy mind, thinking of all the people who are going to benefit from my work, then I am creating a lot of merit doing it.

Let’s sit for a couple of minutes. I call this digestion meditation. Sit for a couple of minutes. Think about what you heard tonight. Review it. Especially remember the important points so that after you leave and in the next few days, continue to think about something that you learned from the talk tonight that was valuable to your practice.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.