Q & A regarding ordination

Venerable Thubten Chodron responds to letters asking about ordination.

On ordination in general: written by Venerable Thubten Chodron in response to questions sent by one of her students who has been practicing for many years.

Anita’s letter

Dear Venerable Chodron,

I’ve been considering ordaining but have some doubts and questions. I live alone, and I feel alone. I have good work as a high school teacher, which gives me satisfaction. I exercise every day and excel at Kung Fu. I have a boyfriend—in fact, in the past I’ve had several boyfriends—however, I’m dissatisfied with me, with who I am, and thus with all aspects of my life.

I know that if I apply the Dharma teachings, all that can change, and when I do put energy into my practice, I feel the benefits. But still my practice is poor and the delights of samsara attract and distract me. But afterwards, I always see that the Dharma is the only way for me to really feel well and happy.

I would like to become a monastic, but I don’t want this to be an escape. How do I know it isn’t? How do I know that this is the correct decision? I don’t have the usual wish to have children, and I believe that this says something.

The other thing that concerns me is if I become a monastic, how will I get food or money to support myself? I remember you said that many monastics have problems surviving in the West. If I ordain but keep wearing lay clothes in the city and working at a job, then nothing has changed to improve my situation for practice.

Warm regards,

Anita,

Venerable Thubten Chodron’s response

Dear Anita,

It’s great that you’re considering becoming a nun and that you’re also examining your motivation, wanting to make sure it’s not one of escaping problems. First, we can’t escape our biggest problems—our ignorance, anger and attachment—just by putting on monastic robes. Those harmful mental states still exist, so we definitely have to practice the Dharma in order to overcome them. The advantage of being ordained is that we have more time to practice and less distraction. We receive the support of other monastics who are practicing and have more opportunity to listen to teachings. Plus, keeping the precepts itself is great purification and we create great merit, which make it easier to develop realizations.

One way to tell if your motivation is to escape problems is to investigate. For example: am I tired of this particular boyfriend or am I tired of having any boyfriend at all? In other words, do you see the situation of having a boyfriend, no matter who he is or how wonderful he is, as filled with problems and being suffering in nature? Or do you just wish to have a better boyfriend? You can examine this for other things you’re attached to (job, money, family, etc.). Of course, we will still have attachment to men until we realize emptiness, but as a nun we’re determined not to follow that attachment. We’re determined to face our attachment, see its disadvantages, and apply the antidotes to it.

Similarly, in terms of being dissatisfied with yourself or feeling lonely, investigate: is the problem external? Do I just want more praise, sweet words, and a nicer environment to feel good about myself? Or is the problem internal, one that comes from mental states that I need to transform?

To become a nun, you don’t need to be a “perfect” practitioner. We become ordained because we aspire to practice and to transform our mind—let go of our faults, cultivate our good qualities, and actualize our Buddha potential.

Before ordaining, arrange to live with other monastics, either in a monastery, abbey, or Dharma center. Living with other sangha and near your teacher is important to be able to keep the precepts. This enables you to study the precepts and have the support of the sangha community in keeping them. From your teacher and the sangha, you will learn what it means to have a “monastic’s mind,” that is, how Buddhist monastics train themselves to act, speak, think, and feel. Having learned this, your practice will go well and your ordination will be a joy for yourself and others. If it will take some time to arrange the proper living situation, I advise that you wait to ordain until that is done.

In the Dharma,

Chodron

On bhikshuni ordination: written by Venerable Thubten Chodron in response to a novice nun (Skt: sramanerika; Tib: getsulma)

Chokyi’s letter

Dear Venerable Thubten Chodron,

I wanted to ask you about gelongma (bhikshuni) vows. I ordained as a novice two years ago, and a year ago, I asked my teacher, Geshe Jampa Gyatso, about taking bhikshuni ordination. He responded, “Not yet.” He told me to talk to nuns who have taken it, to ask questions, and to think about it for a few years. So I’m now slowly beginning to contact some bhikshunis and to find out more. I hope you don’t mind sharing your thoughts with me.

How does it work, on a practical level—preparing for the ordination, taking it, and afterwards? I feel a little hesitant taking vows in another tradition, one that I know nothing about. How do you bridge between the two traditions? Do you remain part of the Tibetan, or are you then part of both? Who is your abbot afterwards? It feels difficult, almost self-defeating, if my abbot will be someone I may never meet again in this life. I think it would be best to learn the language and the context well before taking the vows, and to stay with a community who keeps them for a while at least, but I don’t know if this is possible. I’m torn because I’m aware that studying with Geshe-la, as I’m doing now, is a very fragile fortune. Sooner or later we all will go back to our countries and learn to be stronger and more self-reliant than we expected. Perhaps the need to be our own islands is there as Western sangha, no matter which level of ordination we take and with which tradition. I don’t know. I’m a little confused.

Warmly,

Chokyi

Venerable Thubten Chodron’s response

Dear Chokyi,

Geshe Jampa Gyatso’s advice was excellent. If you proceed slowly, study the bhikshuni precepts, and examine the various issues involved in taking them, then when you do ordain, you’ll be clear and confident.

In terms of preparing for the ordination, I recommend studying the precepts. Read Sisters in Solitude, Choosing Simplicity, and Blossoms of the Dharma. The Chinese tradition usually has a one- or two-month ordination program during which the bhikshuni ordination occurs. Attend the whole program. It’s very valuable.

The Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese ordination lineage is the Dharmaguptaka; the Tibetan is the Mulasravastivadin. They aren’t contradictory. All these lineages are pure and valid. Vinaya lineage concerns our monastic vows. It does not indicate which Buddhist tradition we follow or which philosophical tenet system we adhere to. I haven’t found any problem in being ordained in the Dharmaguptaka Vinaya tradition from China and practicing Tibetan Buddhism. Most of the nuns of the Tibetan tradition who take bhikshuni ordination—whether from the Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese sangha—continue to wear Tibetan robes and do their Tibetan practice. I only know of two who decided to wear Chinese robes and practice in that tradition after ordaining. Personally speaking, I feel very comfortable in Chinese temples and with their practice due to what I learned during and after my ordination program. I feel more like an “international Buddhist” although I mainly practice in one tradition.

In Chinese Buddhism, as in Tibetan Buddhism, masters often send their disciples to a more respected master (a “high lama”) for ordination. While the ordination master is officially our abbot, our original master remains the prominent one who trains and guides us in the Dharma.

Of course learning the language and customs would be wonderful and would afford you the most access to the Chinese Vinaya and training in a Chinese monastery (similarly with learning Korean and Vietnamese and training in their monasteries). However, you can usually find a monastery where some nuns speak English and if you stay there, the master will appoint one or two of them to help you. It’s nice to do that at least for a few months to get the feeling of the bhikshuni sangha, which is very precious. Then you can return to your Tibetan masters and Tibetan studies.

Yes, we Western sangha have to learn to be self-reliant and strong internally in order to keep our precepts. We also have to learn how to be part of a community and to give up constantly focusing on MY Dharma practice and what’s best for MY path to enlightenment. Internally strong and confident monastics, who know how to love, share, take care of, and support each other—it’s a tall call but how wonderful and beneficial it will be to become like that.

All the best,

Chodron

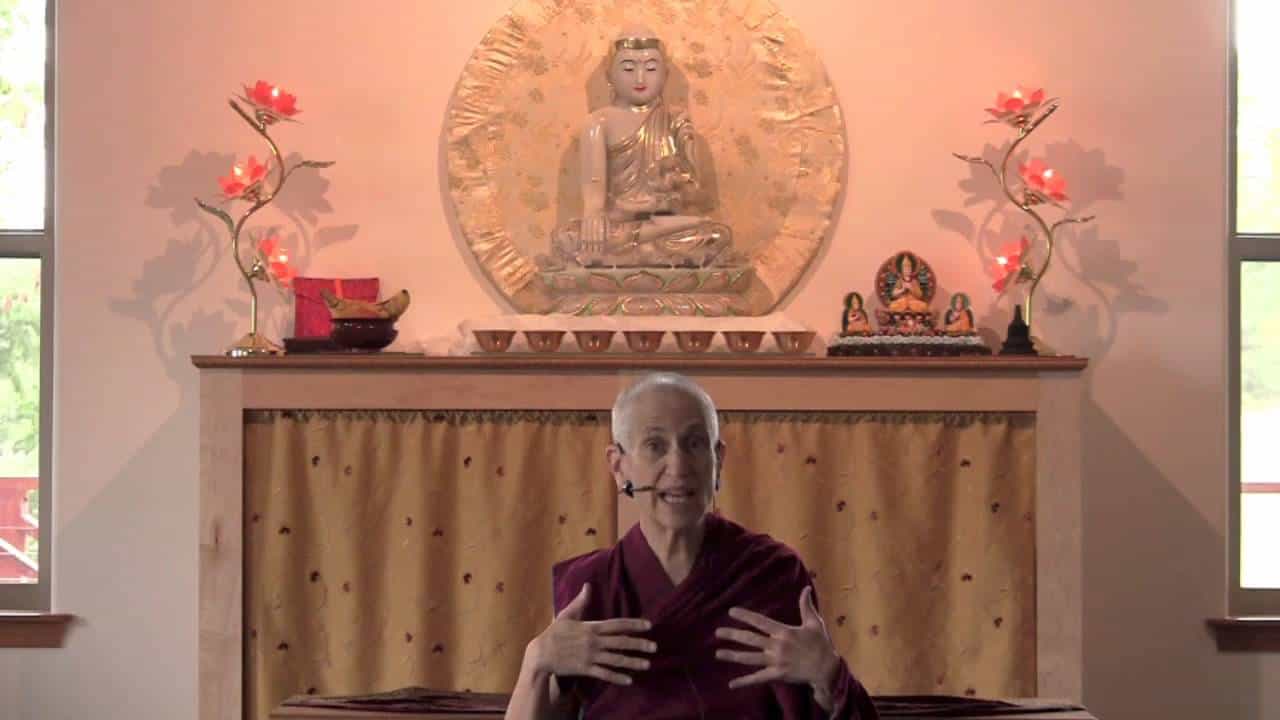

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.