What is a person?

Part of a series of short talks given on Nagarjuna's Precious Garland of Advice for a King during the Manjushri Winter Retreat.

- Trying to find the person amongst the material form of the body

- Examining how the consciousness is not the person

- If the person existed inherently it should be findable

I want to return to these verses by Nagarjuna that His Holiness had recommended to some of us in India. The next series of verses are from Chapter 1 in Precious Garland. Chapter 1 starts out talking about the way to generate the causes for high status (in other words for good rebirth) and for the highest good (for liberation). Under talking about the causes for the highest good he talks about, of course, the wisdom realizing emptiness (or selflessness). So that’s where these verses come—in that kind of context. They’re also quite famous verses, you find them in many different places.

The first one says:

A person is not earth, not water, not fire, not wind, not space, not consciousness, not all of them. What person could there be other than these?

Here when he’s talking about earth, water, fire, wind, and space—those are the five physical elements (or constituents). And then consciousness is the sixth constituent—it’s not something physical. But based on your five material causes, plus the addition of consciousness, then we have the basis of designation for the person. But the person is not its basis of designation.

If the person existed inherently then it should be findable in the basis of designation, amongst these six constituents. But when you look, the person is not earth—we’re not just the solidity of the body. Not water—not the cohesiveness of the body. Not fire—not the quality of heat or maturation, digestion of the body. Not wind—the quality of mobility in the body. Not space—the empty orifices in the body. So we’re not our body. The person also isn’t consciousness.

Now here our mind goes, “Well, I’m not so sure.” Because sometimes we think, “But I am my body.” Yes? Sometimes that comes quite strong, doesn’t it? “I am my body…. If you’re hurting my body you’re hurting me. I am my body.” But then if we reflect on that it’s not terribly difficult to understand that we’re not really our body, that the body is just something material, but that a human being is something much more than something material.

If you’re a scientific reductionist…. I don’t know, they seem to say that you are your body, that the person maybe is the brain. Although that doesn’t make much sense because if you put the brain out there alone that brain’s not going to act like a person. This is not something that scientists, I don’t think, have investigated really well. What is the person? And even what is the consciousness, they’re not sure of. Sometimes they say it’s an emergent property of the brain. But what does that mean? An emergent property of the brain. It’s something that came from the brain. But what is it?

If we look just on a physical level I think it’s not too difficult to say we’re not our brain. We’re not our body. Because if you cut the body open you’re not going to find the person. I mean centuries ago they had this idea of a little homunculus behind the pineal gland, this little person’s hanging out there. But that also had some kind of form, didn’t it? It was like a small person that was hanging out there. And that’s really saying that we are our body, isn’t it? If within our body there’s another miniature person.

It’s good to spend some time and really check: Are you your body? Are you any of the material elements in your body? Are you any of the organs of your body? Any of the limbs? The bones? Really spend some time checking your body and seeing if what the person is is the body.

And then you check: Is the person the consciousness? This one’s harder. Because we have this whole thing: “I think, therefore I am.” So I’m the thinker. Yes? But what’s thinking? Is the person thinking or is the consciousness thinking? Who’s performing the action of thinking? It’s the consciousness, isn’t it? The consciousness is what’s thinking. What are feelings? If you take a look at the Buddhist way of looking at the mind, feelings are a part of consciousness. There are primary minds and mental factors. So feelings (happiness, sadness, pleasure, pain) they’re part of the consciousness. Emotions, too, are part of consciousness. So then, is the person the same as the consciousness? Well if it is, then again, which consciousness?

You might say, “Well, all of those different minds and mental factors together.” But then, which moment of that? They’re all changing. And all those mental factors cannot exist simultaneously because some of them are opposites to each other. Love and hate, and so on. They’re opposites. And you can’t just say the collection of them, because the collection is just a bunch of individual parts.

This requires more time. Because there’s a much stronger feeling that I am my consciousness. And especially when you think of going from lifetime to lifetime, then we say, “Oh, okay, my body dies, my body’s not me.” That’s clear our body’s not going to go on to the next lifetime. But! My mind is going to go on to the next lifetime. And even that’s so in the Buddhist scriptures. So I am my mind. I am my consciousness.”

So we’ll come up with thinking like that. But again, we have to look more closely. And if we are our mind, then which state of mind? Because within one day we have so many different mental experiences, don’t we? Are we the awake mind? The sleeping mind? The dreaming mind? Amongst the awake minds, are we the happy mind? The miserable mind? The spaced-out mind? The alert mind? Are we the angry mind? Are we the wisdom mind? You know? Within one day there are so many different mental states. So can we isolate one of them and say that’s the one that is the person?

So search there. Search through all these different parts of the mind and see if you can find who you are.

We’ll leave it at that right now. You have some homework to do.

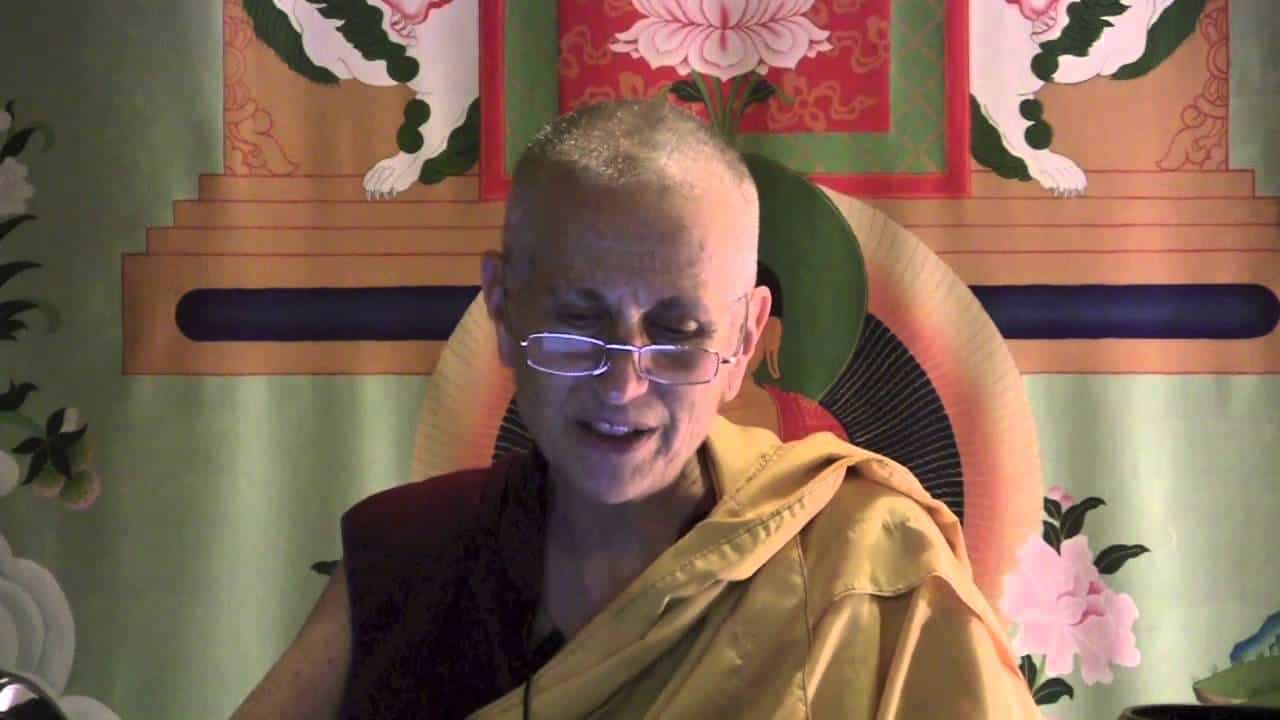

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.