Meditating on emptiness using the four-point analysis

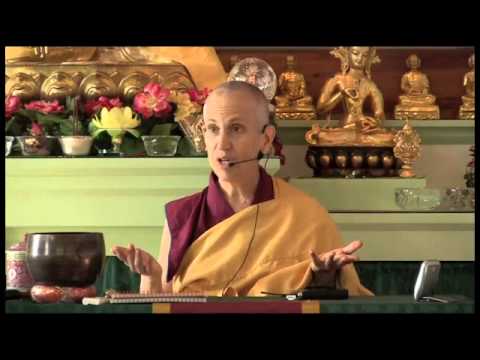

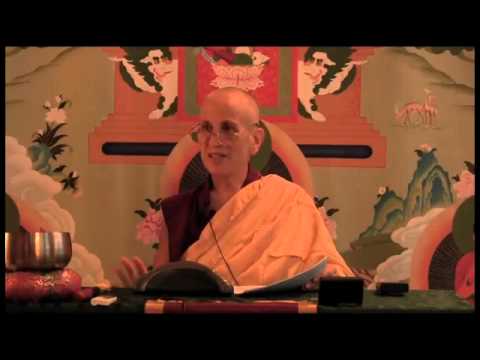

In this Bodhisattva Breakfast Corner talk, Venerable Thubten Chodron discusses errors that can arise as we search for the inherently existent self. An explanation of the four-point analysis as taught by Je Rinpoche.

I would like to talk a little bit about emptiness, because we’re doing the new module, Module 4, that’s going to be on emptiness and the third principle aspect of the path. There is one point that was clarified in my mind a couple of years ago that I was surprised when I heard it. It hadn’t been clear to me before. It is because sometimes the geshes teach it the way I was understanding it. At this point it also came to mind this summer when we were studying with [inaudible] because one of my Dharma brothers, who is really a very good scholar, had the same idea that I used to have too. I think it’s something that I may have explained in that fourth module that there’s a slight adjustment that needs to be made, and some of you may have this too.

In the four-point analysis, the first point is identifying the object of negation. The second point is seeing that if things existed the way they appear to us as truly existent, the way they appear to us, then things would have to be either one and the same with their basis of designation or completely different and unrelated to their basis of designation. Then in the third point, you see if they’re one. The fourth point you see if they are different.

Now the way it is often taught, and this is the way I thought it was supposed to be, is that you’re searching for the inherently existent self to see if you can find it, either in the body or in the mind. That’s the way it’s often explained. Actually, the way Je Rinpoche teaches it, is that you’re not searching for the inherently existent self, you are examining how does the self exist? How does the self exist, and if it were inherently existent, then it would have to be either inherently one and the same with the aggregates or inherently different and unrelated from the aggregates?

You see there’s a subtle difference here. You’re not searching for the inherently existent self. You’re examining how the self exists, and if it were inherently existent, it would have to be either inherently one or inherently different. Then you examine: if it were inherently one, what kind of problems come. There are a lot of problems that come because if the self and the aggregates were inherently one, then they should be the same in number. You have one self, you should have one aggregate. Or if you have five aggregates, you should have five selves.

Then if they were inherently one, actually having a self would be totally redundant because the self is already one of the aggregates, so you wouldn’t even need the word or anything like that. There are all kinds of problems—those are just a few of them.

There are many other problems that arise. Like, you couldn’t experience the karma that you created earlier and so on and so forth. Then similarly, if they were inherently separate, then also you couldn’t experience the karma that you created before. The body and mind could be in one place and the self could be in another place. When you’re doing points three and four, you’re not looking for the inherently existent self, you’re examining how the self exists. If it were inherently existent, it would have to be either inherently one and the same or it would have to be inherently different. That’s what you’re examining. It is a little bit different emphasis than looking for the inherently existent self because you’re just examining this feeling of I, the conventional I—how does it exist? If it were inherently existent, then what would be the ramifications? Those ramifications are absurd, so therefore it can’t inherently exist.

Audience: inaudible

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): No. Why do you identify the object of negation? Because at the beginning you are looking at how things appear to you and how you hold the self to exist. If you look at it as, “Oh, this is the object of negation,” then you’re already lessening the impact, whereas if you get the feeling of “Oh, this is how the I appears to me to exist. This is how I feel I exist,” and you have such a strong feeling that “This must exist; there’s absolutely no question about it.” Like, “If this didn’t exist, then what does exist?”

You have to have that kind of surety in your feeling that I inherently exist for the reasoning to make an impact to show you that it’s impossible to exist the way you feel you do. That is why you identify the object to be negated first, and that’s why you don’t say to yourself beforehand, “Oh this is the object to be negated, so of course I’m not going to be able to find it,” because then it’s making it less strong. Whereas if you feel it, “Oh I’m sure that this exists. This is me. If I inherently existed, then these would be the repercussions.”

Audience: inaudible

VTC: That is why you call up that feeling that’s so strong, and then if the I actually existed, inherently as it appears, then it should be either inherently one or inherently separate, then you show it isn’t, and then,” Oh, well, it can’t exist the way it appears the way I think it does. Oh my god.”

Audience: inaudible

VTC: Yes, because we’re really challenging our own conception of ourselves, so we have to have what that conception is apprehending very clear in our mind. Of course, its apprehended object is erroneous, but we don’t start out saying, “Oh, it’s all erroneous so I already know it doesn’t exist, so now I’m going to prove it doesn’t exist,” because that’s not going to have any impact. It’s like, “Oh wait, this is me. This is how I feel. When somebody says my name or when I just feel me, there’s this feeling inside of like concrete.” Not physical concrete, but mental concrete. That is what you’re examining.

I also saw this summer, through talking with some people, that you have to understand the analogies that the teachers use properly, and you have to understand the adjectives that they use properly. For example, when I say like the inherently existent I appears like a concrete I, some people might misunderstand and think, “Oh, the I appears like something that is form.” Concrete like form, so that there’s some form inside. That’s not the meaning of concrete. Or if we say a solid I, they might think again of something made of form, and that’s not the meaning. Those are words that we use for physical things, but here we’re talking about another way of looking at something. Not that it appears solid or concrete like form, but really and truly there.

There are many things like that, so you have to really listen carefully and make sure you understand, and this is the value of the discussion to make sure we understand properly what’s being said.

Audience: inaudible

VTC: The second point is that if the self existed inherently, as it appears, it would have to be either one with the aggregates or different from the aggregates. There’s no third choice.

If something exists independent from other factors, you should be able to identify it, and there’s only two places you can identify it—it’s either going to be one and the same with the aggregates or it’s going to be something totally different from the aggregates. You’re not going to be able to say that something inherently existent also dependently arises like we were talking about this morning, “It’s inherently existent, but it also needs to be produced.”

No. If it’s inherently existent, it’s got to be either be inherently one or inherently separate. It can’t be both because something that’s inherently existent is independent. It is something that’s got to be discrete and findable like that. You see that there’s no third possibility, a little bit of this, a little bit of that, yes it can be dependent arising and also needs to be produced by causes and conditions. No, none of that makes sense.

Audience: inaudible

VTC: Oh, I’m sorry, it could be independent, but also needs to be produced.

Just to clarify that point for the people who are doing the Module 4 and for everybody else too, who maybe should think about doing Module 4.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.