Living in solitude and living in community

I have been deliberating the differences between practice in solitude and in community. I’m rather alarmed at the tendency I see in many of us who have lived alone for a long time, either in retreat or on our own in some other situation, to get absorbed in our own agenda, our own practice, our own trip. Compassion becomes somewhat theoretical, sentient beings are “out there” somewhere, and we lose the knack of actually taking care of people, being kind and caring and considerate on a daily basis. I see how living in community would be such an effective antidote to this, because every day you have to compromise, practice patience, tune into others’ needs and suffering. In other words, to survive you really have to give up “self-will” as St. Benedict would say—we would call it self-centeredness. I see a dangerous tendency in myself and others who have been in solitude for years to become somewhat rigid and ossified in terms of our agenda and our own way of doing things.

I can see how, in order to get the maximum benefit out of ordination, we really have to live in sangha community. Of course, there is the karmic benefit of keeping one’s vows no matter where we live, but in order to get the benefit of monasticism as a thought transformation practice (“conversion of manners” to quote St. Benedict again) we need to have those rough edges polished off by living with others. I could really see that process, and the results in terms of practice and community harmony when I visited Shasta Abbey and was so enormously impressed. You could really see the supportive container that their community created for their practice; it was so powerful, and palpable.

It also seems clear, as we’ve discussed, that sangha communities will be the key to monasticism surviving, and hopefully thriving, in the West. We Westerners are not so relational, not like Asians who feel such a sense of identity in terms of family, clan, geographical location—even the monasteries in South India have come up with names like “Kongpo Valley Frat House”! But we tend to identify and relate more personally, especially in intimate relationships with partners and close friends. Then when we ordain, we’re asked to give up most of that, but there often isn’t another sense of belonging or community to substitute for it, so often people end up living in an emotional vacuum for years until they finally disrobe out of loneliness and frustration and alienation. I think it is just too hard on people, especially in the beginning, and it’s vital to establish sangha communities to get people on their feet and establish their identity as monastics. I know even for myself, I feel like I’ve been living in isolation ever since ordination, and I need to live in sangha community in order to learn how to be a nun!

Tenzin Chogkyi

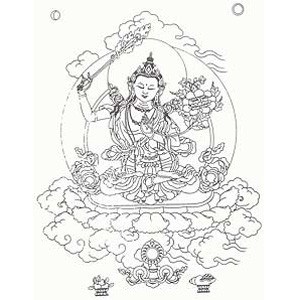

Tenzin Chogkyi is a teacher of workshops and programs that bridge the worlds of Buddhist thought, contemplative practice, mental and emotional cultivation, and the latest research in the field of positive psychology. She first became interested in meditation in the early 1970s and then started practicing Tibetan Buddhism in early 1991 during a year she spent studying in India and Nepal. She worked in administrative positions in several Buddhist centers in the 1990’s, and also completed several long meditation retreats over a six-year period. Tenzin took monastic ordination in 2004 with His Holiness the Dalai Lama and practiced as a monastic for nearly 20 years. Since 2006 she has been teaching in Buddhist centers around the world and taught in prisons for 15 years.