Compassion at a juvenile reformatory

A visit to a facility for children in Michoacan, Mexico

- On January 7, 2003, in Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico, Israel Lipschitz drove Venerable Thubten Chodron, Elana, Gabriela and me to the Juvenile Reformatory after morning Dharma Class. In class, Venerable had said, “Our narrow vision keeps us from the larger happiness of generosity. Give completely and let go. Whatever the receiver does with it after that is fine. The virtue in giving is in the act itself and in the mind of giving: not in the particular gift.” After the freeway underpass, we turned through a gate, onto a bumpy dirt road and arrived at Albergue Tutelar Juvenil del Estado de Michoacan.

In my role as an attorney in the U.S., I had been in juvenile reformatories in the 1970s and 80s. I expected locked doors, metal detectors, screening of identification. But two of the Morelia Dharma members, Laura and Alfredo, had been volunteering at the Reformatory, bringing teachers and other programs to the children there. Along with Israel, they had cleared the way for Venerable to give a teaching. We parked the car and got out. Dust, dry grass, a rough-looking hungry black dog and across a field, three rows of boys in dark green shirts lined up in front of a tall thin guard, dressed in black. The boys ranged from very short to tall, thin young men (ages 9 to 18); a few the same size as my son back home.

Laura and Alfredo greeted us with smiles and we walked down the road into a big gym. It was empty, cavernous, cold, rundown and my heart started to feel heavy. Five girls jumped up from their mats in a small room in the back of the gym and lined up. We chatted with them while boys came in and out with stacks of brown metal chairs, setting up rows facing the stage. Of the five girls, Alejandra spoke a bit of English. She told us her family had been to the U.S. and that she was born in Kansas. Tere, the shortest, had a scar on her face and a large gauze bandage over her left eye. They are 14—15 years old. Many of the children, especially the girls, have suffered serious sexual, physical and mental abuse. Alejandra, more lively than the others, shared that she was going home that day. The others had no idea when they would leave.

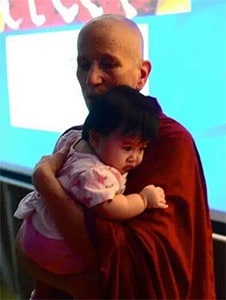

Soon, the hall was filled with these five girls and about 60 boys; 15 of them in white shirts, as they were in a higher risk category. Venerable and Israel (who was interpreting English to Spanish) were seated on the stage; a crucifix and, painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe above. Venerable spoke first about her shaved head, red robes and explained a bit about Buddhism and being a nun. She told the children that they have goodness in them and needed to become friends with themselves. She went on about how to deal with anger: how to notice our physical reactions first, as early signals of it. Leaning forward, she asked the children what happened when they got angry. There was a shy silence. They did not seem used to answering questions from a teacher. Venerable smiled widely, coaxed and finally a boy said that when he got angry, his blood went into his head.

Sometime during this conversation, my mind began to question what good a one-hour Dharma talk could do for these kids. Some of them have committed robbery, assault and murder. Many have been constantly assaulted themselves. I went kind of gray inside. Then I remembered that it was my mind that was doing this. I looked around. The children were mostly listening well, despite much fidgeting. Elana and Gabriela, also from the Dharma Center, looked excited and interested. Venerable and Israel were smiling and working together well. The Director of the Center stood on the sidelines, her large soft arms folded across her chest, looking pleased. One of the guards, a tall young woman was listening closely. I noticed the discouragement, the doubt, was mine. I thought “Well, if I follow this doubt all the way, it leads to the thought that there is no use in even coming here at all. And I doubt if anyone in this room would agree with that.”

On the other hand, if I thought of our presence as a gift, generosity. Giving it and letting go—I pictured Green Tara and her blue utpala flowers. This was all empty of solid, inherent existence—anything was possible. One of these children could become a great leader for peace, a Buddha in this lifetime. How did I know? I didn’t. Another boy opened up, telling us about his drug addiction. He asked what he could do about it. Venerable asked him if the feeling of addiction was more physical or more emotional. He answered without hesitation: “emotional.” Then she talked about working toward a happiness that could fill that hunger—so the craving could subside. She shared that she also took drugs when she was young; then got bored with the highs and lows over and over. He listened carefully, as did many of the others. “How do you show kindness to one another?” Venerable asked. One small boy answered, we are listening now. Another said we help each other go forward. Kindness in a Juvenile Reform School. Yes, I saw that. Venerable gave the children her book: Open Heart, Clear Mind, translated into Spanish. One boy asked her, “What solutions to our problems lie in this book?”. I hoped with all my heart that he would get the opportunity to explore his own wise question.

We ended with chocolate milk and a traditional Mexican cake for the celebration of the January arrival of the Maji, three wise men at the stable in Bethlehem, just after the birth of Jesus. Everyone joined in the snacking—the guards, the Director and the children. Nine-year-old Juanito ran up to Elana and I for his second piece of cake and told us that Jose makes him angry. Jose slowly shook his head and smiled. Elana asked Juanito if he made himself angry. He stared at her and wandered away, then back, and hung around her until we had to go. This was the happiest I had ever felt visiting children in prison. Kindness really is everywhere and can increase.

Zopa Herron

Karma Zopa began to focus on the Dharma in 1993 through Kagyu Changchub Chuling in Portland, Oregon. She was a mediator and adjunct professor teaching Conflict Resolution. From 1994 onward, she attended at least 2 Buddhist retreats per year. Reading widely in the Dharma, she met Venerable Thubten Chodron in 1994 at Cloud Mountain Retreat Center and has followed her ever since. In 1999, Zopa took Refuge and the 5 precepts from Geshe Kalsang Damdul and from Lama Michael Conklin, receiving the precept name, Karma Zopa Hlamo. In 2000, she took Refuge precepts with Ven Chodron and received the Bodhisattva vows the next year. For several years, as Sravasti Abbey was established, she served as co-chair of Friends of Sravasti Abbey. Zopa has been fortunate to hear teachings from His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Geshe Lhundup Sopa, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Geshe Jampa Tegchok, Khensur Wangdak, Venerable Thubten Chodron, Yangsi Rinpoche, Geshe Kalsang Damdul, Dagmo Kusho and others. From 1975-2008, she engaged in social services in Portland in a number of roles: as a lawyer for people with low incomes, an instructor in law and conflict resolution, a family mediator, a cross-cultural consultant with Tools for Diversity and a coach for executive directors of non-profits. In 2008, Zopa moved to Sravasti Abbey for a six-month trial living period and she has remained ever since, to serve the Dharma. Shortly thereafter, she began using her refuge name, Karma Zopa. In May 24, 2009, Zopa took the 8 anagarika precepts for life, as a lay person offering service in the Abbey office, kitchen, gardens and buildings. In March 2013, Zopa joined KCC at Ser Cho Osel Ling for a one year retreat. She is now in Portland, exploring how to best support the Dharma, with plans to return to Sravasti for a time.