Intolerance: Look Into Your Own Mind

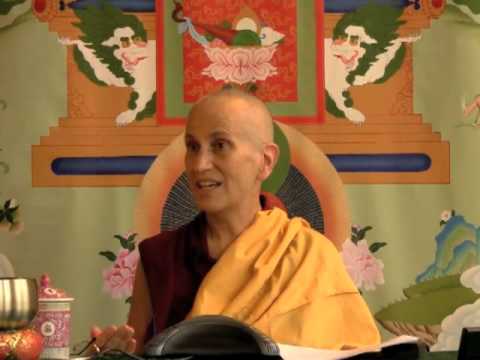

In this talk for the Bodhisattva's Breakfast Corner, Venerable Thubten Chodron reminds us that we must deal with our own mind of intolerance before helping others.

A friend emailed me to discuss intolerance. Somebody told him that if he is intolerant against other people’s intolerance things will work out well, but if he’s tolerant of their intolerance, things won’t work out well. It wasn’t clear in his email whether he was separating out that view or the people who hold the view. It seems to be the idea that if he was intolerant of the people who he thinks are holding this view and acts against those people then it will work out well. There are many elements in this that are completely wrong.

First of all, we need to separate the people and the view that we think they hold. But even before we do that, we need to consider this whole thing of generalizing and making everybody who has a certain characteristic into a big group and then being biased against them. He has been experiencing a lot of fear and anxiety about what he thinks this group of people labeled Muslims are going to do to America. It’s this kind of prejudice going on in his mind. And he realizes this; he’s a Buddhist and wants to think differently. It’s a way of putting all the Muslims together: they are all going to shatter our democracy and create Sharia law and whatever the mind says is going on. This thing of putting all the people who hold this religious faith into a box and imputing traits to them is something that is so dangerous and so vile.

When we see it in our own minds, we really have to do something about it, because this is the whole thing that was behind the Holocaust. It’s the whole thing that lay behind what went on with the genocide in Rwanda. It’s the whole thing that lays behind so many racial and ethnic problems. It’s when people divide into groups and then hold on to that identity and impute characteristics and views on “the other.” Then they hate them.

We all have this tendency. We learn very early as children to put things that look alike in a certain box. Even when we’re in Kindergarten,we learn that anything with three sides we put together here. They have some similarities. Anything with four sides goes over there. We learn to categorize, and it’s a very useful skill in ordinary daily life. There are reasons for categories: men go into this bathroom; women go into this other bathroom. But the thing that doesn’t work is when we impute meanings on those categories that they don’t have.

In this case, it’s “All Muslims think X, Y, Z” and then he’s not only imputing what he thinks they think now but also imputing what he thinks they are going to do in the future. First of all, he doesn’t know at all what these people think, and he doesn’t know at all what they plan to do in the future. We can never take a whole group of people and think they are carbon copies of each other. You really learn that living in a monastery. [laughter] Sometimes people think, “Oh, all these monastics wear the same clothes and have the same haircut and the same religion, so they all must be alike.” Well, you haven’t even been here a week, but you’ve probably noticed we are all different. We don’t come out of a cookie cutter pattern. In any kind of larger group, we can’t impute qualities like that.

This is the same kind of mind that has lain behind so much pain in this world and so much warfare—categorizing people in terms of religions especially. I studied History in college, and it became very clear to me that people were killing each other in every generation in the name of god. For what purpose? It’s very clear that those people don’t even understand their own religion that they are claiming to defend. If people are looking at Muslims and saying, “Oh, they are all thinking this way, and they are all going to do like this,” then actually the people who are imputing that on the Muslims are doing the exact same thing they are accusing the Muslims of doing. They are creating a group identity and imputing false views on them.

It’s not about being intolerant of people who have a certain view. It’s not about being intolerant about the people. We don’t know if all those people in that category have that view. They probably don’t. Second of all, the intolerance should be against any kind of view that puts people in categories and wants to harm them because of that category. If you’re going to accuse others of being intolerant of you because they are Muslim and you are not, then you have to look at yourself and say, “I am intolerant of them because I am whatever religion I am and they are not. They are other. They are different.” What it boils down to is that we’re having the exact same mental state as we’re accusing the other people of having.

If we want to stop intolerance, we have to be intolerant of our own intolerance. [laughter] Like we were discussing yesterday, the Buddha said that hatred is not solved by hatred but by love. So, if we’re intolerant of our own intolerance then we do something to remove it. We try to cultivate love by recognizing the other people have not always been that way, or we use whatever technique will help us overcome this kind of thinking. Then we’ll be successful against our own intolerance. And when we are not intolerant, then we can approach the other people and become friends with them and see that they all don’t fit into a group. They are all individuals and we can’t just throw people in a group and throw them out the window together.

It’s always important to look back on ourselves. This can be quite a difficult and painful process to see our own intolerance, to see our own prejudice against different groups. It’s not pleasant to see in ourselves. But it’s something that we have to look at and overcome. And that work needs to be done in ourselves because it doesn’t matter who has hatred or who has intolerance; either way, it’s something to eliminate. And we have a better chance of eliminating our own than somebody else’s. We have to start with ourselves, and then when we eliminate our own intolerance we can really help people eliminate whatever intolerance they have.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.