The middle way

By S. D.

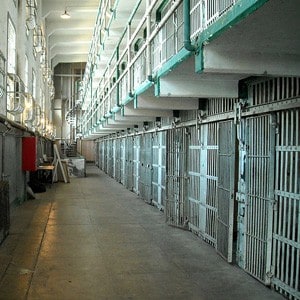

After 26 years inside a maximum security prison, surrounded by stone walls and covered at every angle by gun towers, I was finally transferred to a medium security facility. I now sit in an 8 x 14 foot room instead of a cramped little cell I could hardly move in. A door has replaced the set of bars, and wonder of wonders, I now have a window which, although covered in a secure-screen, can be opened or closed whenever I feel like it.

As pleasant as the move was, I have to admit, it was a real culture shock for me. Suddenly I found myself in a place where the vast majority of the officers and staff, while professional and demanding of respect, always gave respect in return, in some instances going out of their way to make sure I got what I had coming by law as well as through the privileges extended.

The food, while still slopped on a tray and eaten with an oversized orange plastic spork, was prepared with a modicum of care, which meant it was thoroughly cooked, the vegetables cleaned and most everything well seasoned. I especially appreciate the 20- to 30-minute chow time which allows me to actually chew my food and have time left over for some decent conversation with the guys I’m sitting at the table with.

There are so many positive differences I could probably fill up a couple of newsletters with them. Unfortunately, not everyone here shares my sentiments. Last week for instance I sat with a guy at chow who was just transferred into the system with a 10-year sentence. This is his first experience with the judicial system and like most new guys he went on for some time about his ignorance of the law, lack of representation by his lawyer, and his overall difficulty in adjusting to a life spent in a room/cell for 22 hours a day. In the end he confided in me that he had never had much good luck in his life. “I’m a magnet for the negative,” he assured me. “If there’s something bad out there, it always, finds me.”

On one level I couldn’t help but to feel sorry for the guy. But on another I knew the danger he put himself in with such a reckless and negative attitude. Sadly I find that it’s an attitude all too prevalent here, where men with as little as six months to a year left to do on their sentence choose to view themselves as helpless victims trapped in a system they find so overwhelming that they give up without a fight.

All that we are is a result of the way we think and how we choose to deal with the situations we find ourselves in. (Photo by Darwin Bell)

I have always found the teaching of Buddha in direct opposition to this way of thinking. The sutras tell us that all that we are is a result of the way we think and how we choose to deal with the situations we find ourselves in. They stress personal responsibility, self-examination, and the rooting out of negative, self-defeating attitudes that keep us from experiencing the fullness that life has to offer.

Whether we realize it or not, we are responsible for how we deal with every circumstance in our life. It is not some outside force that is buffeting us mercilessly about but instead the culmination of inner thoughts and feeling that naturally project themselves into the outer world.

Ultimately, we are in control. We are the creative force, whether good or bad, behind our lives. If my chow hall companion could realize this, perhaps he wouldn’t be so quick to surrender to that doom and gloom scenario that ensures his time inside prison, and, in the long run, society, will be spent in a state of perpetual fear. Weakness and the unsatisfactoriness the Buddha described as suffering.

Even in a prison cell, we are in complete control of how we are going to deal with our circumstances. For years I gave up on any hope of getting transferred out of a maximum security institution. Counselor after counselor would shoot down my requests, assuring me that without someone on the streets with “connections” who could pull a few strings, the Powers That Be would never let me transfer.

Then one day it suddenly occurred to me that I was trapping myself in the same cycle of abuse as I had been in as a child, simply believing whatever the so-called authority figure in my life at the moment said was true. I accepted the premise, without question that whether because of my sentence, my crime, who I did or didn’t know on the outside, or whatever else, I wasn’t good enough not only to be transferred, but to even be considered for transfer. Until I decided to stop believing the negative, until I chose to try a different route despite the odds, I simply sat in a cramped little cell with whatever cellmate I had at the moment, complaining about how everyone else was getting transferred.

Of course, change requires action. For me that meant a whole lot of five- and six-page handwritten letters detailing my prison record, my academic and vocational achievements, work record and personal growth over the years. I wrote to counselors, assistant wardens, transfer coordinators, even the Director of the Department of Corrections himself.

If I didn’t get a response I wrote again, and then asked friends and family to write, call and fax on my behalf. When I was initially denied transfer I started the whole process over again, refusing to give in to the poor me attitude that told me I was wasting my time. Instead I got back to work and after nearly two years worth of writing letters and with the invaluable support of friends and family who chose to believe in me, the day finally came when an officer walked up to my cell and told me to pack it up. I was transferring in the morning.

I can’t say that what I did would work for everyone. Each of our situations in life is different. What’s the same is our ability to choose how we are going to work with the circumstances and change them either of the good or the bad. One way or another we will work with those circumstances. We will form them according to how we choose to think about them. But we don’t have to buy into the negative, accept defeat and wallow in self-denigration.

We can learn to train our minds to turn every circumstance into a positive. By staying aware of our thoughts and feelings and listening to our inner dialogue we can weed out the negative and replace it with a positive life-affirming attitude that will transform our actions, and ultimately our world, into something far better than what we have settled for thus far. So ask yourself, where do you hope to be in the next couple of years?

Now, get busy making it happen.

Incarcerated people

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.