Path of purification: Vajrasattva practice

Part of a two-day workshop at Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery in Singapore, April 23-24, 2006.

Holiday with the Buddha

- The long-lasting happiness of sincere practice

- Seeing the “dirt” as a necessary part of cleansing the mind

- Different forms of Vajrasattva

- Tips on visualization

- Keeping a focus on being in the presence of a Buddha, not on the details

- Not projecting our authority issues onto spiritual mentors or Buddhas

Vajrasattva workshop, Day 1: Path of purification 01 (download)

Explanation of the mantra

Vajrasattva workshop, Day 1: Path of purification 02 (download)

Forgiving and apologizing

- Afflictions that prevent forgiveness and apologizing

- Setting ourselves up for suffering by holding on to anger

- Focus on our own sincerity and not on the response of others

- The difference between guilt and regret

Vajrasattva workshop, Day 1: Path of purification 03 (download)

Working with the mind

- Seeking and receiving advice

- Learning to transform the complaining mind

- Putting the teachings into practice

Vajrasattva workshop, Day 1: Path of purification 04 (download)

Questions and answers

- Why is someone who has a lot of compassion not able to forgive loved ones?

- Why is acceptance so difficult?

- Business, politics, and precepts

- The meaning of empowerment/initiation

- Getting rid of guilt

- Guilt, regret, and forgiveness

- Should our ability to forgive depend on whether or not the other party intends harm?

- Karma and mental illness

Vajrasattva workshop, Day 1: Path of purification 05 (download)

Click here for Day 2 of the workshop.

Below are excerpts from the teachings.

Holiday with the Buddha

I think that’s the best way to look at it: when we go on retreat, think that we’re going on a holiday with the Buddha; that the Buddha is our best friend, and so it’s going to be a happy holiday.

It’ll be a different kind of happiness; it’s not going to be the happiness of going to the casino [laughter], or the happiness of going to the shopping center, but you’ll come back actually a lot richer from this holiday because you’d have created a lot of positive potential.

When you do retreat, you really begin to see the difference between what we call ordinary happiness and the happiness that comes through very sincere spiritual practice, where our minds get calm and more peaceful. Ordinary happiness is this kind of feeling of excitement of, “Oh, I’m going to get something new … ooo…. goody!” which doesn’t last very long and often leaves us disappointed.

Expect that things will come up

Now of course, to make the mind calmer and more peaceful, sometimes it has to bubble up all the impurities. Whenever we do purification practice, the impurities come bubbling up. We have to clear them away to actually get the experience of a peaceful mind. But that’s okay, because the only way you can clean out dirt is if you can see it.

It’s like when you’re cleaning your house; if you can’t see the dirt, then you can’t clean it. Or if you have a dirty dish, but you can’t see the dirt, then it becomes very difficult to clean your dish. When we do purification practice and our mental dirt comes rising to the surface, that’s okay, because our whole purpose is to be able to clean it out. So when our mental garbage comes floating up, we say, “Oh good! I’m seeing my garbage.”

This is really different from our ordinary way of thinking. Our ordinary way is to think, “Oh garbage…. Get it away, get it away…. Stick it under the table, cover it up! Put something pretty on top of it and pretend it doesn’t exist!” We can do that, but the thing is, the garbage will still be there and it stinks!

Similarly, with our mental garbage, if we try and cover it up and we don’t acknowledge it, it influences all of our actions. It influences our relationships with other people. And it stinks! So it’s much better to let this stuff come up and clear it out, and then our mind is cleaner and brighter.

Different forms of Vajrasattva

There are different forms of Vajrasattva—single, couple form, each with different hand mudras—but the nature of all these different Vajrasattva figures is all the same: it’s all bliss and emptiness. So don’t get too confused over it.

Visualization, why and how to do it

Before we do the Vajrasattva meditation, I just want to talk a little bit about visualization and why we do it. When you first do it, it might seem a little strange, because you may not have done this kind of meditation before. But at some point, we just have to jump in, if you know what I mean. It’s like, “Ok, I don’t understand everything. I don’t get it all. It doesn’t all make sense. But I know it’s a Buddhist practice. I know it’s beneficial. So I’m just going to jump in and try it and see what happens. And keep on learning.”

We need to have that kind of attitude when we start a new practice. Some kind of open-mindedness instead of saying, “I have to understand every little detail. Otherwise, I can’t do it.” We don’t get anywhere with that mind.

So we will be doing a visualization practice. Visualization means we visualize. It doesn’t mean we see with our eyes. So when we’re visualizing Vajrasattva on the top of our head, don’t roll your eyeballs back in your head to try and see Vajrasattva.

It’s a mental image. For example, if I say, “Think of your mother,” do you have an image in your mind of what your mum looks like? Even if your mum is no longer alive, you still have an image in your mind, right? That’s visualization.

Now, of course the image of our mum comes into our mind very easily, because we’re familiar with that. The image of Vajrasattva may not come so easily because we don’t think about the Buddha as often as we think about our mother. So we have to train our mind to become familiar with a new friend, with Vajrasattva. That’s why there is a description of what Vajrasattva looks like. We listen to that and try to develop that image.

Being in the presence of Vajrasattva

When I say, “Think of your mum,” you also get a feeling of what it’s like to be in her presence. In the same way, when we visualize Vajrasattva, part of it involves trying to get a feeling of what it’s like to be in the presence of a fully enlightened one.

Even if you can’t visualize all of the details about Vajrasattva, just getting the feeling that you’re in the presence of a fully enlightened being who has complete love and compassion and accepts you as you are, just having that feeling is very good. That’s what we’re aiming at. So don’t get stuck in all the technicalities of the visualization.

I say this because I have conducted several three-month Vajrasattva retreats, and partway into the retreat, somebody will inevitably raise their hand and say, “What color are Vajrasattva’s celestial silks?” And I go, “Well, you know, I never really thought about it. And I’m not sure which department store he got them at.” [laughter] That kind of thing is more just using your own imagination. You can make the celestial silks whatever color you want. It doesn’t matter how they’re draped on his body. You don’t have to get to that level of detail, especially at the beginning.

When you’re talking to somebody, you may be so engrossed in your conversation with somebody, that you don’t notice what they’re wearing. I never notice what people are wearing. Somebody will say, “Oh, the one in the blue shirt….” Got me! I never look at what they are wearing. But I have the experience of being with that person and I pay attention to other things besides their clothes.

So similarly here, when visualizing Vajrasattva, don’t get too hung up on the details and the technicalities. You’re really going for the experience of feeling that you’re in the presence of an enlightened one.

Not projecting our authority issues

It’s important, when we’re in the presence of an enlightened one, to be relaxed, open and receptive. I say this because often, what we do is we project all of our authority issues on our spiritual mentor and on the Buddhas and bodhisattvas.

You know how we have authority issues: “Oh, there’s somebody in authority. I’d better be good. I’d better look good. I can’t let them know what I’m really doing and thinking inside, because then they will fire me from the job!” We put on a face. We tighten up. We aren’t ourselves. That’s not how we want to be in front of the spiritual mentors and the Buddhas. If we put on a face in front of the holy beings, we’re not going to get anywhere with it. We’re only creating problems for ourselves.

Other people have other types of authority issues: “If somebody is an authority, I don’t like them!” “Try and make me do what you want me to do!”

Have you noticed this? Are you aware of your authority issues? Trying to put on a good face. Being rebellious. Not wanting to listen to instructions simply because we don’t want somebody to tell us what to do. Or, on the other hand, listening so much to instructions that we can’t think for ourselves.

We have all sorts of authority issues, and these will sometimes come up in our Dharma practice when we’re visualizing the Buddha. Our old worldly mind just projects distorted views onto the Buddha, and then we create all of our authority issues.

Here we really have to remember not to relate to the Buddha as an authority in our life. The Buddha isn’t bossing us around. He’s not going to fire us from our job. He’s not judging us. He’s not going to give us an evaluation sheet at the end of the day about our performance. We’re not going to be compared to everybody else in the room. So just let go of all of that stuff, and just create your own personal relationship with an enlightened being who’s looking at you with 100% acceptance.

Vajrasattva isn’t sitting there going, “Oh gosh! I’m sitting on the head of some jerk who’s created all sorts of negative karma!” [laughter] Vajrasattva is not thinking like that. But instead, Vajrasattva is saying, “Oh, this sentient being is overwhelmed by ignorance, anger and attachment and has done so many negative actions because they’ve never been able to learn the Dharma and never been able to actually correct their way of thinking. But now this person wants to really do something positive with their mind.” From Vajrasattva’s side, he’s completely delighted and he’s not judgmental, and his whole wish is to benefit and to help.

I really stress this point because after many years of doing Dharma practice, I realized that even though I had been visualizing Buddhas or bodhisattvas or Vajrasattva or other deities for quite a while, I could never really imagine them looking at me with acceptance. Why? Because I had so much self-judgment that I couldn’t imagine anybody accepting me. This was a really big thing for me. It’s like, “Woh! Look at what my own self-judgment, my own self-criticism is doing to my mind. It’s really blocking me in so many areas and creating so many false concepts!”

Then I said, “Ok, I have to work on this and in the visualizations, really pay attention and let Vajrasattva look at me with acceptance.” Let somebody look at us with compassion instead of us always projecting onto others that they’re judging us and they’re angry at us and they don’t accept us and I don’t belong and all these other kinds of stuff that our garbage mind projects out that doesn’t exist! Do you get what I mean? Okay? So, we really want to see Vajrasattva looking at us with compassion.

Explanation of the mantra

Vajrasattva deno patita: make me abide closer to Vajrasattva’s vajra holy mind.

How do we become close to Vajrasattva? Not by sitting next to him, but by generating the same kind of mental states, by transforming our mind so that our emotions, our thoughts are like theirs.

Suto kayo may bhawa: please have the nature of being extremely pleased with me.

You know what we normally mean or how we normally behave when we want to please our parents or we want to please our teachers? This is not what is meant here.

The Buddha being pleased with us means that we have succeeded in transforming our minds. When our mind is full of love, compassion, acceptance and generosity, then just by our mind being like that, of course the Buddhas are pleased with us.

I emphasize this because sometimes we project our worldly views of what is meant by pleasing somebody onto the Buddhas and bodhisattvas and then we get really tangled up. So it doesn’t mean, “Oh Vajrasattva, be pleased with me. I’m going to put on a good face so that you’ll like me.” It’s not like that.

What this line means is we’re being completely open, we’re transforming our mind. We know that Vajrasattva is encouraging us to do that and is pleased with us for doing that.

Sarwa siddhi mempar yatsa: please grant me all powerful attainments.

Now this doesn’t mean that Vajrasattva is going to do all the work and give us the powerful attainments while we just kind of sleep during the meditation practice. That’s not it. [laughter]

Vajrasattva is also a projection of our own Buddha nature in its fully matured form, i.e. our own Buddha nature that has matured and become a Buddha, that has all the powerful realizations.

When we are addressing Vajrasattva and seeing Vajrasattva as the Buddha that we’re going to be, then there’s not the separation—we’re not thinking that we’re asking somebody who’s separate from us to give us realizations. But rather, we’re bringing the Buddha that we’re going to become into the present moment.

Sarwa karma sutsa may: please grant me all virtuous actions.

We’re expressing our aspiration to do only virtuous actions, to create only the cause for goodness in the world, to create only the cause for upper rebirths, liberation and enlightenment.

Tsitam shriyam kuru: please grant me your glorious qualities.

All of Vajrasattva’s wonderful qualities: the generosity, the ability to manifest in many forms according to the needs of sentient beings, the ability to know skillfully how to help anybody at any particular time, the ability to help with compassion whether other people say “Thank you” or hate you even when you’re trying to help them. So we’re requesting and aspiring to have those same virtuous, glorious qualities ourselves.

Ma may mu tsa: do not abandon me.

Now what’s interesting here is we’re asking Vajrasattva not to abandon us. But Vajrasattva is never going to abandon us. It’s us who’re going to abandon Vajrasattva.

How do we abandon Vajrasattva? We don’t do our meditation practice. We don’t follow Dharma instructions. Our teachers give us practice instructions but we don’t do them.

“I’m too busy lah!” You know that one? That’s number one in our book of excuses of why we can’t practice. We’d much rather watch a television program than be with the Buddha.

“Vajrasattva, I’ll pay attention to you later; I’m busy gossiping on the phone with my friends.”

We’d much rather go out and have a drink with our colleagues than pay attention to Vajrasattva. We’d much rather watch the soccer game or go shopping than pay attention to Vajrasattva.

Vajrasattva has infinite compassion. The Buddhas are never going to abandon us. We’re the ones who abandon them. So even though we’re saying here, “Do not abandon me,” we’re actually saying to ourselves, “I’m not going to abandon the Buddha.”

We are not requesting Vajrasattva to do the work for us

The mantra is like a request to Vajrasattva. But remember, we’re not requesting that Vajrasattva do all these work while we fall asleep. By voicing this request, what we’re really doing is saying in words our own virtuous aspirations, our own spiritual aspirations. We put them in words to remind us of the direction that we want to go in.

Forgiving

What does it mean to forgive?

Who do you need to forgive?

What is preventing you from forgiving that person?

(Besides anger) what else actually prevents you from apologizing and forgiving? Pride is a big one, isn’t it?

“Who? Me? I’m not going to apologize to you. First, you apologize to me!” [laughter]

When we ask what makes it difficult for us to forgive, it’s because sometimes we want the other party to apologize to us first, don’t we? We want them to acknowledge how much we’ve suffered because of what they did. Then, we’ll forgive them. Right?

But first, they have to get down on their hands and knees and grovel in the dirt and say, “Oh, I’m so sorry. I hurt you so much!” And then we can go, “Oh yes, I was hurt so much. Oh! Poor me!” And after they’ve groveled enough, then we’ll say: “Ok, I guess I’ll forgive you.” [laughter].

Are we creating problems for ourselves by thinking in this way? You bet! When we set this stipulation in our mind—that we’re not going to forgive until somebody else apologizes to us—we’re giving away our power, aren’t we? We’re giving away our power because we’re making our ability to let go of our own anger dependent on somebody else. I think forgiving has a lot to do with letting go of anger, don’t you agree? So, we’re effectively saying: “I’m not going to let go of my anger until you apologize, because I want you to know how much I’ve suffered!” [laughter]

So, we set up this kind of precondition in our mind, and then we box ourselves in. Can we make somebody else apologize? No! So then we’re really saying: “Ok, I’m going to hold on to my anger forever and ever and ever, because somebody else isn’t going to apologize.” Who suffers when we hold on to our anger? We do.

When we hold on to a grudge, we’re the ones who will suffer. So we have to let go of the precondition in our own mind that says: “I won’t forgive until they apologize.” Let them do whatever they’re going to do. We can’t control them. But what we have to do is to let go of our anger about the situation, because our anger makes us miserable and keeps us in prison.

We’re so attached to our grudges. We hold on to them. When we make a promise never to speak to somebody again, we never break that promise. [laughter] All of our other promises, we re-negotiate: “I promised that? Oh, I didn’t really mean it.” “I promised this? Oh well, things changed.” But when we promise not to speak to somebody again, we NEVER break it! We really box ourselves in a state of suffering!

What are we teaching our children when we hold on to our anger and grudges?

When we hold on to our anger, when we hold on to our grudges, when we don’t forgive, and when we don’t apologize, what are we teaching our children, especially if you hold a grudge against another family member? You don’t speak to one of your brothers or sisters. What are you teaching your children? When they grow up, then maybe they won’t speak to each other, because they learnt that from their mum and dad, because “Mum and dad don’t speak to their brothers and sisters.” Is that what you want to teach your kids?

Did you all find somebody you need to forgive? Plenty, huh? [laughter] Can you even imagine forgiving others? When you do the Vajrasattva meditation, it’s quite helpful to spend some time imagining forgiving these people. Imagine what your life would be like if you stop hating them and you stop holding a grudge. It’s a very interesting thing just to imagine, and see how much free space there is in your own mind when you’re not holding on to stuff.

Apologizing

What does it mean to apologize?

Who do you need to apologize to?

What is preventing you from apologizing?

I think first of all, we have to work on ourselves, to get ourselves to the point where we feel some regret for our negative actions. Not guilt—we don’t want to beat ourselves up emotionally. But we do regret what we did. We regret what we did because it hurt somebody else, and because that mental state was painful for us and it hurt us as well. So we want to apologize regardless of whether the other person forgives us or not.

The basic thing is we’re cleaning up our own mental mess; whether or not the other party forgives us is irrelevant

Just as we don’t make our forgiving somebody contingent on their apologizing first, we don’t make our apologizing to somebody contingent on their forgiving us afterwards. This is because the basic thing we’re doing when we apologize is we’re cleaning up our own mental mess. When we apologize, we’re the ones who benefit. We’re cleaning up all of our confused emotions, our own mental mess.

Then, when we apologize to somebody, it’s completely up to them whether they accept the apology or not. Whether they accept our apology or not is none of our business. Our job is to feel regret for our negative actions, do the purification and apologize. Their job is to be able to accept the apology.

So even if somebody doesn’t accept our apology, we don’t need to feel bad, because the thing is, we have to check up if we are really sincere in our apology. If we are, then we can have peace of mind that we’ve done our work. We’ve done all we can to ease the situation. We can’t control them. We can’t make somebody else love us again. Or even like us again. But the important thing is that we’ve cleared up our part of what happened. Okay? And that’s always the best we can do, and that’s what we need to do: to clear up our part of it.

Now sometimes, the person we need to apologize to doesn’t want to talk to us. Or it could be they’ve died, and we can’t talk to them. But still, the force of the apology is there and it can be very strong, whether or not we’re able to communicate it directly to the other person.

If somebody isn’t ready to talk to us, we need to give them some space. We can write them a letter. Or maybe we call them on the phone. We try and see what the best way is. And then we just give them space. Or if they’re dead, we imagine them in our mind when we apologize. And we trust the goodness in them to forgive us.

Forgiving ourselves and letting go of guilt

But the main thing is our forgiving ourselves. That’s the main thing. Purification centers a lot on our forgiving ourselves.

Sometimes we have this very distorted notion that if we feel really guilty and we feel really terrible, it will somehow atone for the pain we cause somebody else.

Does your feeling guilty stop somebody else’s pain? It doesn’t, does it? Your guilt is your own pain. It doesn’t solve somebody else’s pain. To think that the worse I feel, the more guilty I feel, the more shameful and evil and hopeless and helpless I feel, then the more I’m really purifying—that’s another one of our stupid ways of thinking.

What we want to do is to acknowledge the mistake, forgive ourselves so we don’t hold onto that kind of regret, confusion and negative feeling, and then let go. We don’t want to go through our whole lives carrying big sacks of guilt on our back, do we? I heard of a teacher who asked his students who felt guilty, to wear a knapsack with bricks in it, and walk around all day with this knapsack full of bricks. That’s basically what we’re doing to ourselves on a mental and spiritual level when we feel guilty.

Practices such as the Vajrasattva practice enable us to clear those things up. We have regret for our negative actions, we do the purification, we let go. We don’t have to carry around those bad feelings forever and ever. We have so much human potential and so much goodness in ourselves, to waste our time feeling guilty doesn’t make much sense.

We do need to feel regret for our mistakes. Regret is important; but regret and guilt are not the same thing. When we act in harmful ways, we can regret them, but we don’t have to feel guilty.

You’re the only one who can tell what’s going on in your mind and assess whether you’re feeling regret or guilt. It’s up to you to determine as an individual. This is where having a meditation practice is very helpful, because you become more and more aware of your different mental states, and you’re able to tell the difference between regret and guilt. Then you cultivate regret, you forgive yourself, you let go. But you don’t cultivate guilt.

Working with the mind

I find that people don’t usually listen to the advice they get anyway. [laughter] I can’t tell you how many people come and talk to me, hour after hour; I give them advice, they go and do the exact opposite! Sometimes I think I should tell them the exact opposite, and then maybe they’ll do what they need to do. [laughter]

“Yes, but….” Good advice is usually not something the ego likes to hear.

But the thing about seeking advice is sometimes we feel, “Oh, if I just talk to somebody, they’ll tell me what to do.” But the thing about advice is that people don’t usually tell us what our ego wants to hear, because good advice is usually not something that our ego likes to hear.

When we have a problem and we go and talk to somebody, “Oh, so and so did this, and they did that ….” What we really want is for them to say to us, “Oh, poor you, you’re absolutely right! This person is really harmful. They’re really bad. You have every right in the world to feel sorry for yourself.” Then we say, “Well, what do I do to improve the situation?” And they have to say, “Oh well, it’s all their fault anyway, so there’s nothing you can do.” [laughter]

So often when we ask people for advice, this is what we want. We want pity or sympathy. But somebody who’s going to give you really good advice is going to tell you exactly what you don’t want to hear. They’re going to tell us that we have some responsibility in the conflict or in the unhappy situation, and until we’re able to loosen our own rigid concepts and think that maybe we have to change our approach, until we get to that point, then no amount of advice goes in, because we’re stuck in our own rigid opinions.

Sometimes people call me and they tell me a problem, and I say, “Do this.” They reply, “Yes, but….” and they go on and on for another half an hour. And then I say another two sentences and they say, “Yes, but….” and they go on for another half an hour. [laughter] Sometimes after they say “Yes, but…,” three or four times, I’ll say, “What do you think you should do?” And then there’s silence at the other end of the phone, because they’re not thinking about what they can do. They’re not thinking, “What part am I responsible for in this mess? How can I change what I’m saying, what I’m thinking and what I’m doing?” They’re not thinking about that. They just want to go on and on and on with their story.

You know about our perfection of complaining. There’s perfection of generosity, perfection of ethical discipline, etc, AND the “perfection” of complaining. We’ve mastered that one. [laughter] We haven’t mastered generosity, ethical discipline, patience, joyous effort, concentration and wisdom yet, but Singaporeans have mastered the “perfection” of complaining AND the “perfection” of shopping. [laughter] Unfortunately, I’m not very good at giving you wise instructions on how to master those two “perfections.” [laughter]

When we do the Vajrasattva practice, we have to sit on the cushion with ourselves. We have nobody else to complain to but ourselves, so we play our same old sob story over and over again in our meditation. Instead of doing 100,000 mantras, we do 100,000 “Poor me, poor me, poor me….” Who says we have no single-pointed concentration? Single-pointedly, we can go over and over, and over again the horrible things that somebody did to us. How they betrayed our trust. How mean they were to us. How we did nothing to deserve this. We can meditate single-pointedly. It doesn’t matter if a car drives by or a dog barks; we’re not going to get distracted. Even if it’s lunch time, we keep meditating, “They did this, they did that….”

So when we’re doing the Vajrasattva practice, we see what’s really going on in our mind, and then we realize that the Dharma teachings we’ve been receiving all this time are meant to be practiced. Yes, we got to practice them. We don’t just listen to the teachings. We don’t just write them down in notebooks. We don’t just stock our house with books. But we actually try and put into practice what the teachers have been teaching us, because nobody else can put it into practice for us; we have to do the practice ourselves.

So if we’re unhappy with someone, if we’re unhappy with something, if we’re confused about what we need to do with our lives, we need to sit down and meditate on the teachings the Buddha gave. If you sit down and meditate on the teachings the Buddha gave, and after some time—like a few weeks or a few months—you still don’t have it sorted out, then you can seek some advice. But so often, instead of thinking for ourselves, we run to somebody else and then we don’t even listen to the advice that person gives us. True or not true? [Laughter]

So I think the meditation practice is very valuable for that reason. We have to learn to work with our own mind.

Questions & Answers

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Did you find the discussion useful? What are some of the points that you came up with? What are some things that came out of the discussion that were meaningful for you?

Audience: The common denominator is anger.

VTC: The common denominator is anger. Ok, so what do you mean by that? What prevents you from apologizing and forgiving? Is it usually anger? Yes. What else actually prevents apologizing and forgiving?

Audience: Having pride.

VTC: Yes, pride is a big one, isn’t it? “Who? Me? No… I am not going to apologize to you. First you apologize to me.” [laughter]

Sometimes what makes it difficult to forgive is we want somebody else to apologize to us first, don’t we? We want them to acknowledge how much we suffered because of what they have done, then we will forgive them. Right? But first they have to get down on their hands and knees and grovel in the dirt [laughter] and say, “I am so sorry I hurt you so much,” and then we can comment, “Oh yes, I was hurt so much. Oh, Poor me, poor me, poor me!” [laughter] And after they’ve groveled enough, we will say, “Ok, I guess I forgive you.” [laughter].

Are we creating problems for ourselves? You bet! To set the stipulation in our mind that we are not going to forgive until somebody else apologizes is to give away our power. We are making our ability to let go of our own anger dependent on somebody else. Because forgiving has a lot to do with letting go of anger, don’t you think? We’re saying, “I am not going to let go of my anger until you apologize. Because I want to know that you know how much I’ve suffered.” [laughter]

We set up this kind of precondition in our mind, and then we box ourselves in. Can we make somebody else apologize? No! Then we are saying, “I am going to hold on to my anger forever and ever and ever because somebody else is not going to apologize.” Who suffers when we hold on to our anger? We do!

When we hold on to a grudge, we are the ones who suffer. So, we have to let go of the precondition in our own mind that says, “I won’t forgive until they apologize.” Let them do whatever they are going to do. We can’t control that, but what we have to do is let go of our anger about the situation, because our anger makes us miserable, and our anger keeps us in prison.

Arrogance and pride won’t let us forgive or won’t let us apologize because we are so attached to our grudges; we hold on to them. When we make a promise never to speak to somebody again, we never break that promise. [laughter] All of our other promises we renegotiate. “Oh, I promised that, but I didn’t really mean it.” “I promised this, but oh well, things changed.” I promise never to speak to somebody again—never! [laughter] We just really box ourselves in to such a suffering state.

Then, when we hold on to anger and grudges, we don’t forgive, and we don’t apologize. What are we teaching our children? As parents, what examples are you setting for your children when you don’t forgive other people or when you don’t apologize to other people? What are you teaching your kids? What are you teaching them especially if you hold a grudge against another family member, when you don’t speak to one of your brothers and sisters. When they grow up then maybe they won’t speak to each other because they learned that from mom and dad, because mom and dad didn’t speak to their brothers and sisters. Is that what you want to teach your kids?

I say this because I came from a family in which that happened. I just remember that they had some kind of a summer home where they all went. There were four flats in the summer home, and the family that lived in one of the flats were our relatives, but I was not supposed to speak to them. [laughter] They were cousins. I think my grandmother and their grandmother were sisters. I forget what it was. All I knew was that they were relatives but I was not supposed to talk to them. I had no idea what happened two generations ago. It was not my generation or my parents’ generation but my grandparents’ generation. I don’t even know what happened, but we were not supposed to talk to that family.

Then I saw that what existed on the level of my grandparents’ generation—with siblings not talking to each other—slowly began to happen amongst my aunts and uncles in the family. This uncle would not talk to that aunt, and that aunt did not talk to this one, and this one did not talk to that one. Then, horror of horrors, I started seeing it in my generation with all my cousins not talking to each other because of this and that. They all found their own unique reason to hold a grudge. It wasn’t the same grudge that happened in my grandparents’ generation. [laughter]

They could find new and creative reasons to hate each other. It was so shocking to watch that and say, “When this happens in a family, it carries on through the family.” Because what children learn is not so much from what their parents tell them to do but what their parents do. What a tragedy! I wonder if this is going to happen to all my nieces and nephews and my cousins’ children, and if they are all going to find reasons not to talk with each other.

Really think about it: If you are in a family in which this kind of stuff happens, do you really want to participate in that?

Do you remember when Yugoslavia broke up and you had all the Republicans fighting each other? It was all about something that happened a few hundred years ago. All the people who were killing themselves in the 1990s were not alive a few hundred years ago, but because this grudge about the other ethnic groups had been passed on from generation to generation, finally it exploded several hundred years later. Is that stupid or is that stupid? “I’m going to kill you because my ancestor and your ancestor—who both lived a few hundred years ago—were in some kind of ethnic dispute, and therefore we can’t be friends.” Stupid! So, we have to be careful that we do not let our mind get caught in that kind of thing.

Did you all find somebody you need to forgive? Plenty, huh? [laughter] Can you even imagine forgiving? It’s quite helpful, as we do the Vajrasattva meditation again after the break, to find some time imagining forgiving these people. Imagine what your life would be like if you stopped hating them, and you stopped holding a grudge. It is a very interesting thing just to imagine. How much free space would there be in your mind when you are not holding on to stuff? What about apologizing? Did you all find somebody you need to apologize to? Plenty of those also? Sometimes apologies can be very flippant: “oh, I am sorry.” Then we know that’s not a real apology, is it? We are not talking about other people apologizing to us; we are talking about the quality of our apologies.

First of all, we have to work on ourselves to get to the point where we feel some regret for our own actions. Not guilt—we don’t want to beat up ourselves emotionally, but we do regret what we did. We regret what we did because it hurt somebody else and because that mental state was painful for us, and it hurt us as well. We want to apologize regardless of whether the other person forgives us or not.

Just as we don’t make our forgiving somebody contingent on their apologizing first, we don’t make our apologizing to somebody contingent on their forgiving us afterwards.

The basic thing to do when we are apologizing is to clean up our own mental mess. When we apologize we are the ones who benefit. We are cleaning up all of our confused emotions—our own mental mess. Then, when we apologize to somebody, it is completely up to them whether they accept the apology or not. Whether they accept it or not is not our business, because our work was feeling the regret during the purification and the apology on our part. Their work is to be able to accept the apology. Even if somebody doesn’t accept it, we don’t need to feel bad. Because we have to check up if we were really sincere in our apology, and if we were, then we feel that peace of mind that we have done our work. We have done all we can to ease the situation.

We can’t control it. We can’t make somebody else love us again, or even like us again, but the important thing is that we have cleared up our part of what happened. That’s always the best we can do and that’s what we need to do—to clear up our part of it.

Sometimes the person we want to apologize to doesn’t want to talk to us. Or sometimes they’ve died and we can’t talk to them. But still, the force of the apology is there and it is still very strong whether we were able to communicate it to the other person or not. So, if somebody is not ready to talk to us, we just need to give them some space—maybe we write it in a letter and send it, or maybe we call them on the phone. We try and see the best way to do it, and then we just give them space. Or if they’re dead, in our mind we imagine them and we apologize, and we trust their own goodness to forgive us.

The main thing is forgiving ourselves. Purification centers a lot around us forgiving ourselves. Somehow, we have this very distorted notion that if we feel really guilty and terrible, that is going to atone for the pain we caused somebody else. Does feeling guilty stop somebody else’s pain? It doesn’t, does it? Your guilt is your own pain. It doesn’t stop somebody else’s pain. To feel like: “The worse I feel, the more guilty I feel, the more shameful and evil and hopeless and helpless I feel—then I am really purifying,” is another one of our stupid ways of thinking.

What we want to do is to acknowledge the mistake, forgive ourselves so that we don’t hold on to that kind of regret, confusion, and negative feeling, and then let go. We do not want to go through our whole life carrying big sacks of guilt on our back, do we?

I heard of a teacher once who asked his students who felt guilty to walk around wearing a knapsack with bricks in it all day. That is basically what we are doing to ourselves on a mental and spiritual level when we feel guilty—we’re carrying around bricks. I think that’s why when people get old, they get bent over. [laughter] They are bent over with all their regrets, all that guilt. Whereas a practice like Vajrasattva enables us to clear those things up. We have regret, we do the purification, we let go. We do not have to carry around those bad feelings forever and ever. We have so much human potential and so much goodness in ourselves that to waste our time feeling guilty doesn’t make much sense.

We do need to feel regret for our mistakes. Regret is important, but regret and guilt are not the same thing. For example, if I accidentally knock this ceramic cup over and it breaks, I regret it. Do I feel guilty about it? No. There is no reason to feel guilty; it was an accident. But there is regret. It’s the same thing when we act in harmful ways—we can regret that, but we don’t have to feel guilty. You are the only one who can tell what is going on in your mind, and assess whether you’re feeling regret or guilt. That’s up for you to determine as an individual.

Having a meditation practice is very helpful because you become more and more aware of your different mental states, and you are able to tell the difference between regret and guilt. Then you cultivate regret, you forgive yourself, and you let go—but you don’t cultivate guilt.

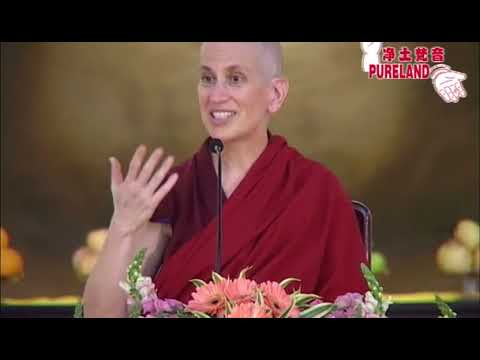

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.