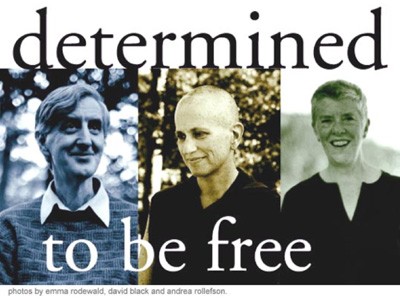

Determined to be free

What is renunciation and how does it make sense in modern life?

This is an excerpt from an article written by Clea McDougall, editor of ascent magazine, who interviewed Brother Wayne Teasdale, Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron, and Swami Radhananda in 2003. For the full article, click here to access ascent's archives.

I find myself talking with a swami, a monk, and a buddhist nun. I want to find some humour in this, there’s got to be a joke you could tell, but really, I feel a little unsettled. Good unsettled. Unsettled in that way you feel when you are maybe a little dejected but then hope creeps in …

Here are three real people, who have committed their lives to paths of renunciation. Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron, an unassuming, clear and curious Buddhist nun, Swami Radhananda, our soft-spoken powerhouse of a columnist, and Brother Wayne Teasdale an interesting mix of Christian monk/sanyasi making his way as an urban mystic.

I gather them together to dispel some of the myths around renunciation, to redefine renunciation for modern practitioners. Who isn’t curious about the lifestyle of a monk? Who hasn’t wanted to ask, what is it like for them? and How can we, who aren’t quite ready for life as a swami, still practice renunciation?

The renunciates are from three very different traditions, but they share an essential truth. What strikes me is how much they have been inspired by their own teachers, and how the commitment to spiritual life because a service to others, a way of giving back. Renunciates have a role beyond their own evolution, they act as symbols of the possibility in spiritual aspiration and intent. Their renunciation does not mean that they have turned away from life but that they fully engage in their true responsibilities to the world.

I start off by jumping right in and asking, What is this thing we call renunciation?

Brother Wayne Teasdale: It’s really the renunciation of, or freedom from, what we would call in the Christian tradition the false self, the egoic consciousness, or the self-cherishing attitude. Leading up to that, as a monastic, there is renunciation of some of the usual joys and pleasures of this life, including owning property and having a family and things of that nature. But that’s just the beginning of renunciation.

Swami Radhananda: For me, renunciation is going toward something. As a renunciate, I have made a choice where I want to put my energy and how I want to live my life. It’s knowing the teachings and then having the opportunity to share them with other people. The clearer I become on this path, the more that drops away. Also, I only take what I need. I let go, but at the same time other things come to me. So it’s a real contradiction in some ways. I just know that with renunciation my life has expanded and so has my vision. It’s a dynamic process of evolving consciousness. When I took sanyas, I began to understand that there was a lot more to renunciation than letting things go. It’s a commitment to facing life and moving forward.

Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron: It’s a determination to be free from cyclic existence with all of its unsatisfactory conditions, and an aspiration to attain to liberation or full enlightenment. From a Buddhist perspective, we’re renouncing suffering and the causes of suffering. I would suggest in a Buddhist way, instead of using the term “renunciation,” we call it a determination to be free. “Renunciation” often has such a negative connotation, but it is actually a very joyful spiritual aspiration.

Clea McDougall: Not all of us can take vows or dedicate our lives to renunciation. What are some practical ways that everyday people can practise renunciation?

Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron: The first thing is to simplify one’s lifestyle. Even though renunciation is an inner attitude, it should be displayed in how we live. How do we express the renunciation of selfishness in our lifestyle? Living more simply and not consuming more than our fair share of the world’s resources. Seeing our impact on the environment and other beings, we become more mindful and reduce our consumption, reuse what we have, and recycle.

Swami Radhananda: On a more subtle level, people can also renounce the images they hold of people who are close to them or people as they meet them, by suspending judgement. This allows people to change and for their fullness to come forward. A lot of times, people are attached to their ideas and concepts. Here in BC this summer, with the forest fires, people have had to ask, “What am I going to take with me?” as they were evacuated from their homes. The community has become really strong in helping each other. Things aren’t as important. Compassion and caring become the focus. Sometimes life and Mother Nature will demand that of people.

Brother Wayne Teasdale: We can have a very, very committed, disciplined, regular practice. Like meditation. A practice of mindfulness in each moment. I think renunciation is a practice in meeting people. It’s just to accept them. You don’t accept their actions, but you accept them as a person. By constantly evaluating people, it’s a diminishment of the other. So instead of engaging in diminishing the other, you just accept them as like yourself and don’t make any judgement about where they’re at and just be there, present for them. And you know, if they need something in terms of insight or encouragement or love and acceptance, then they will ask for that. So I think that’s a positive way to practise renunciation in human relationships.

The participants

Brother Wayne Teasdale is a lay monk, author and teacher. In 1986 he responded to a call from his close friend and teacher, Father Bede Griffiths, the English Benedictine monk who pioneered interreligious thought and practice. Brother Wayne traveled to Griffith’s ashram in India and was initiated as a Christian sanyasi. Following the initiation he expressed a wish to stay at the ashram, but Griffiths encouraged him to return home. “You’re needed in America, not here in India,” Griffiths said. “The real challenge for you is to be a monk in the world, a sanyasi who lives in the midst of society, at the very heart of things.”

Brother Wayne has carried out the counsel of his teacher by pursuing a mystic path while making a living and working for social justice. Actively seeking the common ground between spiritual traditions, Brother Wayne is a trustee of the Parliament of the World’s Religions and a member of the Monastic Interreligious Dialogue. He teaches throughout the world and currently lives at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago.

Brother Wayne’s books include The Mystic Heart(2001), A Monk in the World: Finding the Sacred in Daily Life (2002), and Bede Griffiths: An Introduction to His Interspiritual Thought (2003).

Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron spent most of her early life near Los Angeles where she studied and worked as a school teacher before devoting her life to Buddhist teachings. Her initial contact with Buddhism inspired her to face the challenges of her daily life. “The more I investigated what the Buddha said,” she says, “the more I found that it corresponded to my life experiences.” After many years of study, Chodron received full ordination as a nun in l986.

Having lived and taught in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Israel, Chodron is now based in Idaho while she searches for a location for a future study center, Sravasti Abbey. The abbey will be a spiritual community where monastics and those preparing for ordination, male and female, can practice according to Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Chodron is a great supporter of monasticism as a path of liberation and selfless service. “There is much joy in ordained life,” she explains, “and it comes from looking honestly at our own condition as well as at our potential. We have to commit to going deeper and peeling away the many layers of hypocrisy, clinging and fear inside ourselves. We are challenged to jump into empty space and to live our faith and aspiration.”

Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron’s books include Open Heart, Clear Mind (1990), More on this book… (2001), and Working with Anger (2001). For information on her teachings, publications, and projects visit these websites:

www.thubtenchodron.org and www.sravastiabbey.org.

Swami Radhananda is a yogini, ascent columnist and spiritual director of Yasodhara Ashram in Kootenay Bay, BC. She met her spiritual teacher, Swami Sivananda Radha, in 1977. “At the time,” she says, “I was struggling with an underlying feeling of absence in my life. I was married, had two children and a career—but something was still missing.” Swami Radha’s teachings touched her immediately. “She spoke about the purpose of life and how to live life fully. She spoke about bringing quality and Light into every aspect of our lives.” For many years Radhananda lived as a householder yogi, integrating the philosophy and practices of yoga into her work as mother, teacher and education consultant. She became president of Yasodhara Ashram in 1993 and was initiated into the order of sanyas soon after. As a swami, her main concern has been making the teachings of yoga accessible to everyday practitioners, especially youth.

Today Radhananda devotes her time to writing, teaching and supporting a widespread community of students and teachers in reaching their potential through self-reflection and the study of yoga.

Radhananda most recently published a video and CD that instructs students in a standing meditation, The Divine Light Invocation (2003). To find out more about Swami Radhananda and Yasodhara Ashram, visit the website at www.yasodhara.org.