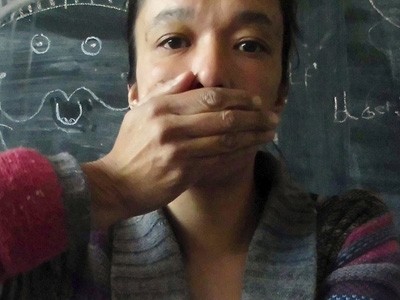

Speaking of the faults of others

“I vow not to talk about the faults of others.” In the Zen tradition, this is one of the bodhisattva vows. For fully ordained monastics the same principle is expressed in the payattika vow to abandon slander. It is also contained in the Buddha’s recommendation to all of us to avoid the ten destructive actions, the fifth of which is using our speech to create disharmony.

The motivation

What an undertaking! I can’t speak for you, the reader, but I find this very difficult. I have an old habit of talking about the faults of others. In fact, it’s so habitual that sometimes I don’t realize I’ve done it until afterwards.

What lies behind this tendency to put others down? One of my teachers, Geshe Ngawang Dhargye, used to say, “You get together with a friend and talk about the faults of this person and the misdeeds of that one. Then you go on to discuss others’ mistakes and negative qualities. In the end, the two of you feel good because you’ve agreed you’re the two best people in the world.”

When I look inside, I have to acknowledge he’s right. Fueled by insecurity, I mistakenly think that if others are wrong, bad, or fault-ridden, then in comparison I must be right, good, and capable. Does the strategy of putting others down to build up my own self-esteem work? Hardly.

Another situation in which we speak about others’ faults is when we’re angry with them. Here we may talk about their faults for a variety of reasons. Sometimes it’s to win other people over to our side. “If I tell these other people about the argument Bob and I had and convince them that he is wrong and I’m right before Bob can tell them about the argument, then they’ll side with me.” Underlying that is the thought, “If others think I’m right, then I must be.” It’s a weak attempt to convince ourselves we’re okay when we haven’t spent the time honestly evaluating our own motivations and actions.

At other times, we may talk about others’ faults because we’re jealous of them. We want to be respected and appreciated as much as they are. In the back of our minds, there’s the thought, “If others see the bad qualities of the people I think are better than me, then instead of honoring and helping them, they’ll praise and assist me.” Or we think, “If the boss thinks that person is unqualified, she’ll promote me instead.” Does this strategy win others’ respect and appreciation? Hardly.

Some people “psychoanalyze” others, using their half-baked knowledge of pop psychology to put someone down. Comments such as “he’s borderline” or “she’s paranoid” make it sound as if we have authoritative insight into someone’s internal workings, when in reality we disdain their faults because our ego was affronted. Casually psychoanalyzing others can be especially harmful, for it may unfairly cause a third party to be biased or suspicious.

The results

What are the results of speaking of others’ faults? First, we become known as a busybody. Others won’t want to confide in us because they’re afraid we’ll tell others, adding our own judgments to make them look bad. I am cautious of people who chronically complain about others. I figure that if they speak that way about one person, they will probably speak that way about me, given the right conditions. In other words, I don’t trust people who continuously criticize others.

Second, we have to deal with the person whose mistakes we publicized when they find out what we said, which, by the time they hear it, has been amplified in intensity. That person may tell others our faults in order to retaliate, not an exceptionally mature action, but one in keeping with our own actions.

Third, some people get stirred up when they hear about others’ faults. For example, if one person at an office or factory talks behind the back of another, everyone in the workplace may get angry and gang up on the person who has been criticized. This can set off backbiting throughout the workplace and cause factions to form. Is this conducive for a harmonious work environment? Hardly.

Fourth, are we happy when our mind picks faults in others? Hardly. When we focus on negativities or mistakes, our own mind isn’t very happy. Thoughts such as, “Sue has a hot temper. Joe bungled the job. Liz is incompetent. Sam is unreliable,” aren’t conducive for our own mental happiness.

Fifth, by speaking badly of others, we create the cause for others to speak badly of us. This may occur in this life if the person we have criticized puts us down, or it may happen in future lives when we find ourselves unjustly blamed or scapegoated. When we are the recipients of others’ harsh speech, we need to recall that this is a result of our own actions: we created the cause; now the result comes. We put negativity in the universe and in our own mindstream; now it is coming back to us. There’s no sense being angry and blaming anyone else if we were the ones who created the principal cause of our problem.

Close resemblances

There are a few situations in which seemingly speaking of others’ faults may be appropriate or necessary. Although these instances closely resemble criticizing others, they are not actually the same. What differentiates them? Our motivation. Speaking of others’ faults has an element of maliciousness in it and is always motivated by self-concern. Our ego wants to get something out of this; it wants to look good by making others look bad. On the other hand, appropriate discussion of others’ faults is done with concern and/or compassion; we want to clarify a situation, prevent harm, or offer help.

Let’s look at a few examples. When we are asked to write a reference for someone who is not qualified, we have to be truthful, speaking of the person’s talents as well as his weaknesses so that the prospective employer or landlord can determine if this person is able to do what is expected. Similarly, we may have to warn someone of another’s tendencies in order to avert a potential problem. In both these cases, our motivation is not to criticize the other, nor do we embellish her inadequacies. Rather, we try to give an unbiased description of what we see.

Sometimes we suspect that our negative view of a person is limited and biased, and we talk to a friend who does not know the other person but who can help us see other angles. This gives us a fresh, more constructive perspective and ideas about how to get along with the person. Our friend might also point out our buttons—our defenses and sensitive areas—that are exaggerating the other’s defects, so that we can work on them.

At other times, we may be confused by someone’s actions and consult a mutual friend in order to learn more about that person’s background, how she might be looking at the situation, or what we could reasonably expect from her. Or, we may be dealing with a person whom we suspect has some problems, and we consult an expert in the field to learn how to work with such a person. In both these instances, our motivation is to help the other and to resolve the difficulty.

In another case, a friend may unknowingly be involved in a harmful behavior or act in a way that puts others off. In order to protect him from the results of his own ignorance, we may say something. Here we do so without a critical tone of voice or a judgmental attitude, but with compassion, in order to point out his fault or mistake so he can remedy it. However, in doing so, we must let go of our agenda that wants the other person to change. People must often learn from their own experience; we cannot control them. We can only be there for them.

The underlying attitude

In order to stop pointing out others’ faults, we have to work on our underlying mental habit of judging others. Even if we don’t say anything to or about them, as long as we are mentally tearing someone down, it’s likely we’ll communicate that through giving someone a condescending look, ignoring him in a social situation, or rolling our eyes when his name is brought up in conversation.

The opposite of judging and criticizing others is regarding their good qualities and kindness. This is a matter of training our minds to look at what is positive in others rather than what doesn’t meet our approval. Such training makes the difference between our being happy, open, and loving or depressed, disconnected, and bitter.

We need to try to cultivate the habit of noticing what is beautiful, endearing, vulnerable, brave, struggling, hopeful, kind, and inspiring in others. If we pay attention to that, we won’t be focusing on their faults. Our joyful attitude and tolerant speech that result from this will enrich those around us and will nourish contentment, happiness and love within ourselves. The quality of our own lives thus depends on whether we find fault with our experience or see what is beautiful in it.

Seeing the faults of others is about missing opportunities to love. It’s also about not having the skills to properly nourish ourselves with heart-warming interpretations as opposed to feeding ourselves a mental diet of poison. When we are habituated with mentally picking out the faults of others, we tend to do this with ourselves as well. This can lead us to devalue our entire lives. What a tragedy it is when we overlook the preciousness and opportunity of our lives and our Buddha potential.

Thus we must lighten up, cut ourselves some slack, and accept ourselves as we are in this moment while we simultaneously try to become better human beings in the future. This doesn’t mean we ignore our mistakes, but that we are not so pejorative about them. We appreciate our own humanness; we have confidence in our potential and in the heart-warming qualities we have developed so far.

What are these qualities? Let’s keep things simple: they are our ability to listen, to smile, to forgive, to help out in small ways. Nowadays we have lost sight of what is really valuable on a personal level and instead tend to look to what publicly brings acclaim. We need to come back to appreciating ordinary beauty and stop our infatuation with the high-achieving, the polished, and the famous.

Everyone wants to be loved—to have his or her positive aspects noticed and acknowledged, to be cared for and treated with respect. Almost everyone is afraid of being judged, criticized, and rejected as unworthy. Cultivating the mental habit that sees our own and others’ beauty brings happiness to ourselves and others; it enables us to feel and to extend love. Leaving aside the mental habit that finds faults prevents suffering for ourselves and others. This should be the heart of our spiritual practice. For this reason, His Holiness the Dalai Lama said, “My religion is kindness.”

We may still see our own and others’ imperfections, but our mind is gentler, more accepting and spacious. People don’t care so much if we see their faults, when they are confident that we care for them and appreciate what is admirable in them.

Speaking with understanding and compassion

The opposite of speaking of the faults of others is speaking with understanding and compassion. For those engaged in spiritual practice and for those who want to live harmoniously with others, this is essential. When we look at others’ good qualities, we feel happy that they exist. Acknowledging people’s good qualities to them and to others makes our own mind happy; it promotes harmony in the environment; and it gives people useful feedback.

Praising others should be part of our daily life and part of our Dharma practice. Imagine what our life would be like if we trained our minds to dwell on others’ talents and good attributes. We would feel much happier and so would they! We would get along better with others, and our families, work environments, and living situations would be much more harmonious. We place the seeds from such positive actions on our mindstream, creating the cause for harmonious relationships and success in our spiritual and temporal aims.

An interesting experiment is to try to say something nice to or about someone every day for a month. Try it. It makes us much more aware of what we say and why. It encourages us to change our perspective so that we notice others’ good qualities. Doing so also improves our relationships tremendously.

A few years ago, I gave this as a homework assignment at a Dharma class, encouraging people to try to praise even someone they didn’t like very much. The next week I asked the students how they did. One man said that the first day he had to make something up in order to speak positively to a fellow colleague. But after that, the man was so much nicer to him that it was easy to see his good qualities and speak about them!

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.