Working with Buddhists behind bars

An interview by Andrew Clark with Venerable Thubten Chodron and Santikaro Bhikkhu regarding their prison work

Andrew Clark: What do you make of the fact that with roughly 2 million people currently incarcerated, the United States has the largest population of people in prison in the world? What does this say about us?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: We’re suspicious of others, we’re fearful, and we don’t want to think about what causes people to get involved in crime. It seems like voters are more interested in protecting themselves from people who they think will harm them than preventing young people from growing up to be criminals. So citizens are willing to vote for a new prison, but they don’t want their tax money spent on schools, education, and after-school projects for youth. They aren’t making the connection that if young people grow up in poverty, without education, without skills, if they grow up in a family that’s a mess, it’s very natural for them to get into criminal activities. It makes perfect sense why they landed where they did. I think we have to start looking at the cause and remedying that.

Also, I think the idea of “Punish them!” reflects a broader American policy of “Use might to solve problems.” This is the same kind of attitude we have toward how to deal with Al Qaeda, the Palestinians, and anybody else who does anything we don’t like. We use force against our own citizens, and other countries, and there seems to be this idea that “I’m going to treat you really badly until you decide to be nice to me.” It doesn’t work on a foreign policy level, and it doesn’t work with people who have gotten involved with criminal activities.

Punishing people doesn’t make them want to be nice. It makes them bitter and angry. They stay in prison and don’t learn skills. Later they’re released without any kind of preparation for facing the world. It’s a setup for recidivism, which is one of the reasons why prisons are so crowded. People get out and go right back in because they don’t know how to live in the world. The prison system doesn’t teach people how to live in the world; its only focus is punishment.

Santikaro Bhikku: And the punishment doesn’t just happen within prison, it continues after they are released. They are highly restricted as to jobs they can get; many of them come from neighborhoods where work is hard to come by anyway. And some of the jobs that do exist aren’t open to them because they’re convicted felons. Well, they have to eat; they might have a wife who wants child support, and the only way some of them know how to make money is illegally. Also, supposedly they’ve done their time, but for the rest of their lives they can’t vote. What does that say about our belief in democracy?

There’s an assumption here that people can’t be rehabilitated. If we really believed that people could be rehabilitated, we would send them through a rehabilitative program; we’d let them vote and get jobs. But the punishment continues—in some cases, throughout their lives.

Can society make some effort to create jobs for people who are released from prison, who will then have a chance to show that they can do the job? For example, let’s say a person is out of prison for five years, has a job, and doesn’t cause any trouble. That should be enough proof that he’s changed. Society should create opportunities, such as giving tax breaks to employers who hire people released from prison, just as we should do for employers who hire disabled people. There could even be foundations that specialize in this. After all, we let white-collar crooks get away with murder.

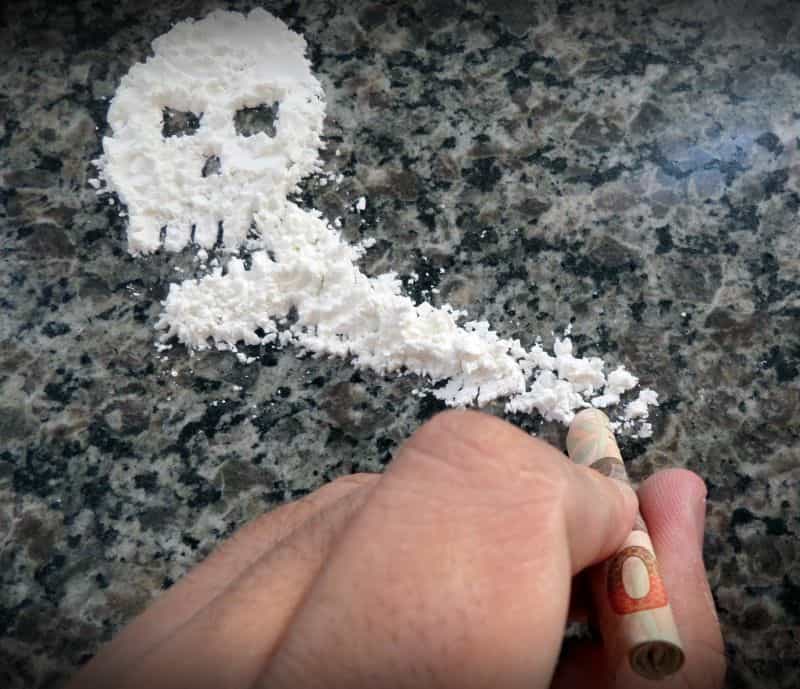

Blaming and scapegoating is a major part of why people don’t look at the causality behind crime. Drugs are a clear example. African-Americans, especially, go to prison on drug charges with sentences that are two, three, or four times what whites serve for the same crime. That to me is clearly scapegoating. We have yet to deal with our racist heritage, and that includes us liberals. Many white people have a knee-jerk belief that blacks commit more crimes, and that’s not based on evidence. We’re afraid and we don’t want to look into the causes of the fear. It’s a lot easier to scapegoat blacks or, if you’re in the middle class, poor people. It functions as denial: we don’t want to look at the violence in our own lives and that our lifestyles perpetuate.

Andrew: I want to ask you about some disturbing statistics I’ve seen: 65 percent of people committing felonies lack a high school education, 50 percent were under the influence of either alcohol or drugs when they perpetrated the crime, and another 33 percent are unemployed. How do you think these statistics contribute to the typical stereotype of felons–that they were born to be criminals?

Santikaro Bhikku: If 50 percent are under the influence of something, how do we interpret that? One interpretation could be that these people are all lazy bums, they’re drunks, they’re druggies, they’re scum. My way of looking at it is to ask why they are using drugs or alcohol. What are the causes of that in their social background?

We should also remember that alcohol is the drug of choice in our society, and all classes are abusing it. So if you’re drunk while you’re committing white-collar crime, does anybody keep that statistic?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: There’s a difference between violent crime and white-collar crime. White-collar crime is carried out over a period of time. You don’t just fudge the books one day, you fudge every day, for years. The people who are in prison for violent crimes, something got a hold on them, then “Boom!” There they were. It’s a very different type of activity. In a violent crime, there’s a lot of strong emotion, and the strong emotion catches people’s attention, it makes them afraid. Whereas when people hear about a business that is dumping toxic waste into a river, it doesn’t produce that powerful, immediate effect the way it does when people hear about murder or rape.

Andrew: Given that half of the 2 million people in jail or prison in the U.S. are African American, while African Americans make up only 13 percent of the total population nationwide, have you found that many of the incarcerated people who attend your teachings/meditations are African American?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: It depends a lot on the group, but generally, no. In some prisons a group will be half, or sometimes two-thirds African American, but mostly a group is predominantly white, with a few African Americans. Some prisoners have remarked about that to me, saying that they’d like more people of color to come. But often the African Americans, if they’re looking for another religion, will look to Islam, where they feel their identity or their roots are.

Santikaro Bhikku: Another factor is that there is strong pressure on blacks to stay in the church, the various Protestant denominations, because that’s such a part of many black communities. Also, the Nation of Islam created an African American identity for itself. To convert to Islam is acceptable to some black families, but to become a Buddhist may be considered a betrayal of both family and the whole race, because they see the church as so much a part of their identity. I haven’t heard this from people in prison but I have heard it from other African Americans.

Andrew: Have you seen any correlation between the type of people attending the teachings and meditations, and the type of crime they are doing time for, or the length of sentence?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Almost everyone I write to in prison is in for violent crimes. The last time I was at San Quentin, of the roughly 40 people that came, most were lifers. Afterward, I asked them about this. They said that most of the people who are in for life are much more likely to seek out spiritual things, and also programs for change, because they recognize that their whole life will be spent in prison. So they want to make the most of it. People who are in for shorter periods of time—say, for robbery, or a short drug term—are often angrier. They’re already thinking about what they’re going to do when they get out—all the fun they’re going to have. Also, the people who are in with short sentences tend to have more contact with the outside because their families haven’t cut them off. They are also more related to gangs and what’s happening on the outside.

Santikaro Bhikku: In many cases, we don’t know what the individual crimes are; incarcerated people tend not to talk about that in front of the group. When I find out, it’s usually through private communication.

Andrew: How has this work affected your practice?

Santikaro Bhikku: I find these guys inspiring. When I hear them talk about the situations they struggle with, and I meet people who are committed to practicing in much more difficult circumstances than I have to deal with, that’s inspiring. So are those who are dealing with AIDS, cancer, extreme poverty, or rape. I think of these people when I’m feeling lazy or complaining.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Some of the guys I write to have committed the crimes that most terrify me. What is interesting is that I’m able to go beyond my fear of what they’ve done and see them as human beings. When they write letters, the stories they tell me pull at me sometimes. For example, someone in solitary will write about his loneliness and being cut off from his family. Then there’s the pain of those who live in the big dorms. People are constantly in their face, day and night, in very dangerous situations. The fact that they turn to the Three Jewels for refuge, and that it helps them, inspires me about the efficacy of Dharma practice. Seeing how some of these guys change over time and learn to deal with their stuff, that’s very inspiring also. They tell me what they used to be like, and yet here they are, open and willing to look at stuff inside themselves. I always feel that I receive much more than I give.

Andrew: Do you think that being a Buddhist monastic changes the way you go about doing the prison work, or the way incarcerated people respond to you?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Sure. You’re wearing the “Buddhist uniform,” so, just as in the rest of society, they relate to you in a different way–whatever their preconceptions happen to be. Some people are more suspicious of you, others respect you more. The men I write to get a sense of commitment from the fact that I’m a nun. Many of them have had difficulty with commitment in their lives. Also, they may feel starved for sense pleasure, but here we are, we’ve voluntarily given it up and we’re happy! They think, “Oh, they’re happy and they’re doing without the same things I’m doing without. Maybe I can be happy without that stuff too!”

Santikaro Bhikku: A lot of prison staff perceive me as clergy, and to some extent give me more respect than if I were a layperson. Prison is a very hierarchical system. Also, a lot of guys identify with me more easily than with the lay volunteers. As they’ve put it, they can’t have sex, I can’t have sex; they have to follow lots of rules, I have to follow lots of rules; they don’t have much choice of clothes, I don’t have choice! Some of the men picture their cells as monastic cells, even if they don’t really know what a Buddhist monastery is like.

Andrew: How does this work fit in with the life of a Buddhist monk or nun?

Santikaro Bhikku: Prison is a good place to practice socially engaged Buddhism. Prison brings together a lot of social issues in this country: racism, poverty, class, violence in society, rigid hierarchy, and militarization. Also, it’s challenging for me as a monastic in this country, where it’s still so easy to get away with a middle-class existence. Our Buddhist centers are overwhelmingly middle class, or even upper middle class. We have a lot of places with nice gourmet food and all kinds of little privileges. Working with incarcerated people is one way I’m trying to have a connection to people who do not have middle-class privileges or backgrounds.

Another aspect of my life as a Buddhist monk is to share Dhamma, and these are just more human beings who are interested in Dhamma. A prison is such a brutal, hierarchical, paramilitary system—and here we are meditating! And it’s not just about the incarcerated people, by the way. The guards are not very privileged people either. They are, for the most part, poorly paid and not well respected. How many people want to grow up to be a prison guard?

If some of the big companies were to invite me to go in and give Dhamma talks, I’d go there too. If Dubya invited me down to Texas for some meditation discussions, I’d go.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: If incarcerated people were on the outside, they might not go to Buddhist centers, which often are not in neighborhoods where they would feel comfortable going. So prison work is a very precious opportunity to connect with and touch people in a way that you don’t have on the outside.

Some of the most moving experiences I’ve had in prison were when I’ve given refuge, or precepts. When I give the precept not to kill to someone who’s killed, it really moves me. I’ve been so amazed at the discussions I have with the men in the prison groups. They are in an environment where nobody wants to listen to them, where nobody cares about what they think. When they come in contact with somebody who’s genuinely interested and wants to know what they think, they open up.

Sometimes I have the choice to teach at a Dharma center or drive three hours to see a person in prison. I’d rather go see the person in prison! We know that person is going to take in what we say, whereas often people on the outside act as if the teacher has to be entertaining. They don’t want the talk to be too long. They have to be comfortable. Sometimes people on the outside aren’t quite as motivated to practice as guys on the inside are.

Andrew: What would be your advice to someone who is interested doing prison work?

Venerable Thubten Chodron: Be very patient with the bureaucracy. Be firm, don’t give up, be patient. Push, but push gently. Be respectful of the staff.

Santikaro Bhikku: Don’t think you can cut corners or not follow the rules, because the one who will pay the price isn’t you—it will be those who are incarcerated. Examine your class and race issues. I’ve met volunteers who come off as superior because they’re more educated or from a “higher” class. Effective volunteers are willing to look into their own class bias and lingering racism.

Venerable Thubten Chodron: And look into your own fear, your own prejudice against “criminals,” and your own fear of being hurt. Look at your motivations. Are you thinking that you’re going to convert these people and put them on the right path, or are you going in there with respect for them?

Santikaro Bhikkhu was born in Chicago, grew up in the Peace Corps in Thailand, and ordained as a bhikkhu in 1985. He translated Mindfulness with Breathing and other books by Ajahn Buddhadasa.

Andrew Clark, 27, is an aspiring monk in the Tibetan tradition. He began his monastic training in Augusta, Missouri, with Bhikshuni Thubten Chodron and Santikaro Bhikkhu, and now lives with the Eight Precepts at Nalanda Monastery in southern France, where he is continuing his training for ordination.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.