Good practices: Ancient and emerging

Environmental practices of American monastic communities

A talk given at Gethsemani 3 in May of 2008.

The Buddha didn’t give teachings on world environmental issues. 2600 years ago, there were seas of jungle with wild animals and only small islands of civilization. The earth was not encumbered by humanity; she held all beings quite easily.

However, after thinking about this topic for a number of weeks, I concluded that the Buddha was still the most brilliant, astute environmentalist in the history of our world. He focused not on the outer environment but on the ecology of the inner life. After seeing aging, sickness, and death as well asbeing a wandering ascetic for the first time, he began to explore what was this suffering that he saw—the origin of this suffering as well as the path that freed one from suffering. Buddha identified and eliminated the poisons (attachment, anger, and delusion) within his own mind that caused his suffering. With the pollution removed, the vast clear and knowing nature of his mind was revealed. This restoration of his inner ecosystem illuminated the virtuous qualities within his mind to a radiant perfected state.

With this restored vast and open mind imbued with all the virtuous qualities we can only imagine, he walked the world, and those who were inspired and compelled to emulate him became the first monastics. He taught them with this inner ecology field guide (the four noble truths, the eightfold path, or the three higher trainings) in order to help them nourish and sustain their inner lives so they could live harmoniously with each other and with the world.

The beauty of this practice of inner ecology is that it is shared by other spiritual traditions, especially the practices of compassion, interdependence, and simplicity, which have no religious exclusivity to them. His Holiness the Dalai Lama includes them in all his talks on secular ethics.

Now that Buddhism has come to the West, American and Canadian Buddhist monastics are continuing this beautiful lineage of inner sustainability in their communities. Our commitment to practice ethical discipline, live simply, experience the interdependence of all things, be mindful and content—and at the same time be innovative and extremely creative thinkers that look outside the box of what the world believes is possible in regards to the planet—is already happening. It is simple yet profound.

We as monastics have the most conducive circumstances to bring this about, which we can then share with those who meet us, learn about us, and are inspired by us. They can then look towards their own innate good hearts and find the deep wisdom to restore their own inner environments to that pure state. We want to model for them a happy life without an excessive lifestyle.

But the world, as we well know from our own experience of working on our minds, is more complicated than in the Buddha’s time. The distractions and cravings are more numerous, the fear and anxiety more prevalent.

Michael Pollan, who writes for The New York Times, recently wrote an article called “Why Bother” in which he states that our culture is going through not only a crisis of lifestyle but also a crisis of character. The inner environment of many westerners (and, in my view, of Americans in particular) is stressed from the poison of intense dissatisfaction and craving. Michael Pollan states, “Virtue these days is a term of derision, or liberal soft-headedness. For a culture that prides itself on individualism, we are conformists continually trying to fit into our culture’s view of success or fame. The sum total of everyday choices made mostly by us (the consumer who contributes 70% to the economy) is mostly made in the name of our needs, desires, and preferences.” This I believe has brought much of the outer environmental crisis to this critical point, because the inner environment is so disturbed, agitated and smoldering. Reining in our desires is seen as unpatriotic and oppressive. “I want what I want when I want it” has become the mantra of our culture. So virtuous lifestyles that reflect contentment, simplicity, and ethical discipline seem out of date in the face of our culture’s high-speed greed and addiction to success, sense pleasures, and reputation.

However, there is hope as models for a new paradigm. I have gathered some wonderful examples of Buddhist monastic communities in America and Canada that live within a spiritual ecosystem yet,by example, support the well-being of others outside that system. They live simply yet are unafraid to try what many naysayers say is too difficult, too restrictive, or too late. I would like to thank Bhante Rahula from Bhavana Forest Monastery, Reverend Master Daishin from Shasta Abbey, Venerable Sona from Birken Forest Monastery, Venerable Tarpa from Sravasti Abbey, and Naniko Bhikkhu from Abhayagiri Monastery for taking the time to respond to my questionnaire that focused on what their communities are doing in terms of good inner and outer environmental practices. I would like to acknowledge the Asian–Buddhist monastic communities who have helped the Dharma flourish in the West in its pure form. How they integrate the field guide of the Buddha in their inner and outer environments would be worth a presentation all by itself.

I have highlighted some of the responses to questions I sent that I found inspiring and informative.

- What Buddhist principles or teachings has your monastery translated into environmental practices for ways of doing things within daily community life, and in terms of your building structures, use of resources, care of the land?

All of the monasteries practice simplicity of lifestyle or the ethics of frugality. Car pooling by community members as well as lay supporters is highly encouraged. Each of the communities recycles stringently, and repairs and reuses wood, metal, appliances, and furniture. Sravasti Abbey guides its supporters when they donate food, encouraging them out of respect for the environment to purchase minimally packaged items. The food offerings are brought in cloth grocery bags rather than plastic or paper bags.

Abhayagiri Forest Monastery encourages their supporters not to buy bottled water since their well water at the Abbey is quite good. The manufacturing of plastics is environmentally unhealthy and when liquid is heated or frozen in the bottles it releases poisons.

All of the monasteries depend on the kindness of others and eat only what’s offered. They are also prudent with the monetary offerings given to them and the monastics have few personal possessions.

All of the communities practice harmlessness and protecting life, seeing all living things as worthy of care and respect. Bhavana Forest Monastery uses Have–A-Heart traps and other creative non-violent techniques to minimize harm to living things like snakes yet keep the residents safe.

All the monasteries eat a vegetarian diet. Sravasti Abbey purchased a ewe and her two lambs when they heard that a neighbor would be butchering them. They found them a home with a vegetarian shepherdess who was looking to add to her flock for wool spinning.

Each of the monasteries has unique forest stewardships for their lands. Bhavana sees their monastery as a “precious jewel in the green forest.” They are currently trying to prevent the Allegheny Power Company from building a new 200-foot wide right of way through the forest adjacent to their property to install a new 500Kv transmission line. They are encouraging them to use instead an already existing right of way further down the road and double stack the wires on taller towers to preserve acres of undisturbed forest.

Birken Forest Monastery in Canada has an 80-acre bird sanctuary that is left undisturbed without structures on it. They also leave the fallen wood to decompose and for habitat.

Sravasti Abbey uses the dead standing wood in their forest for firewood and has begun an ambitious project of thinning areas of their 240-acre property for fire safety.

Both Birken and Abhayagiri use solar power for their electricity needs and Abhayagiri is hoping to decrease their use of propane for heat in the near future. Sravasti Abbey will be using a geo-thermal system to heat their new monastic residence which is being built this year.

Finally all feel that silent or solitary retreats for their community members are crucial for the individual’s inner ecology.

- What individual or group patterns or ways of thinking have been the most challenging for the community to change in its efforts to live what the Buddha taught?

All the communities pointed out in their responses that conditioned consumer habits are hard to break for community members and that restraint, although not easy, does help conserve resources. Novices are older now and have built up life patterns that can be challenging to change. Younger community members raised in a disposable culture do not think of repairing appliances, computers or printers, but rather put them in the closet and suggest buying a new one. Another challenge is for community members to see the tools and supplies at the monastery as their own and to treat them with care.

Shasta Abbey feels that green office and cleaning supplies help take care of the planet, but they warn of a kind of green snobbery that may arise if communities are not careful. Supplies offered with a pure heart should be used. At Sravasti Abbey, the residents educate their lay supporters in the use of green cleaning supplies, which helps everyone transition away from environmentally harsh products.

- What role in the environmental movement do you see the Buddhist monastic community playing in inspiring and influencing the lay public at the grass-roots level as well as the larger connection through writings, Internet and teachings?

Abhayagiri believes that many monastics are well educated about global warming, although not outspoken. Birken Forest Monastery holds a Green Monday where lay supporters and the monastics have group discussions about ecology and care for the planet. The teaching on dependent origination, says Bhavana,can help people see how everything arises due to causes and conditions and that there is a rippling effect in all that we do. The forest monasteries also see themselves as “refuges of green.” The Buddha himself was born, attained enlightenment, and passed away in Parinibbana, all out in nature underneath a tree, and not for lack of any buildings. This has a hidden message—that the vibrations of nature have a subtle, healing affect on our minds. The forests can teach us so much about life. So this should encourage us to try and preserve as much of the rapidly depleting natural environment as we can. That should be the message and mission of the forest monasteries—to serve as refuges and be the last bastions against the onslaught of rampant materialism threatening to swallow up the islands of green.

Shasta Abbey and Sravasti Abbey both feel that lay practitioners look to the monastics for help in coping with our fast-spinning modern world. In some ways they watch us to see how we do things and how we deal with the world.

Sravasti Abbey has held a retreat on environmentalism. Venerable Chodron, the abbess of Sravasti Abbey, incorporates environmental issues in many of her teachings and has written about it in her book, Path to Happiness. One of the main topics is seeing that the “us versus them, friend versus enemy” polarizations can be huge obstacles to positive change.

So as you can see, the American and Canadian Buddhist monastic communities are not only integrating the Buddha’s field guide of good environmental practices on the inside, they are also translating them to the outside. Not to say that we don’t have a lot of work to do. Issues around feeding large groups of people without filling bags with Styrofoam and non-reusable plastics are becoming more frequent. How much driving do our kind lay supporters do to make up for the driving we don’t do? What forums are appropriate for monastics as far as sharing and networking with the public around the environment? What can we learn from others? How do we connect with the world where our practice and lifestyles could be used as role models for others?

These questions will be answered as time goes on, and the Buddhist monastic communities will confront these issues as they arise. May we all benefit from their efforts and example.

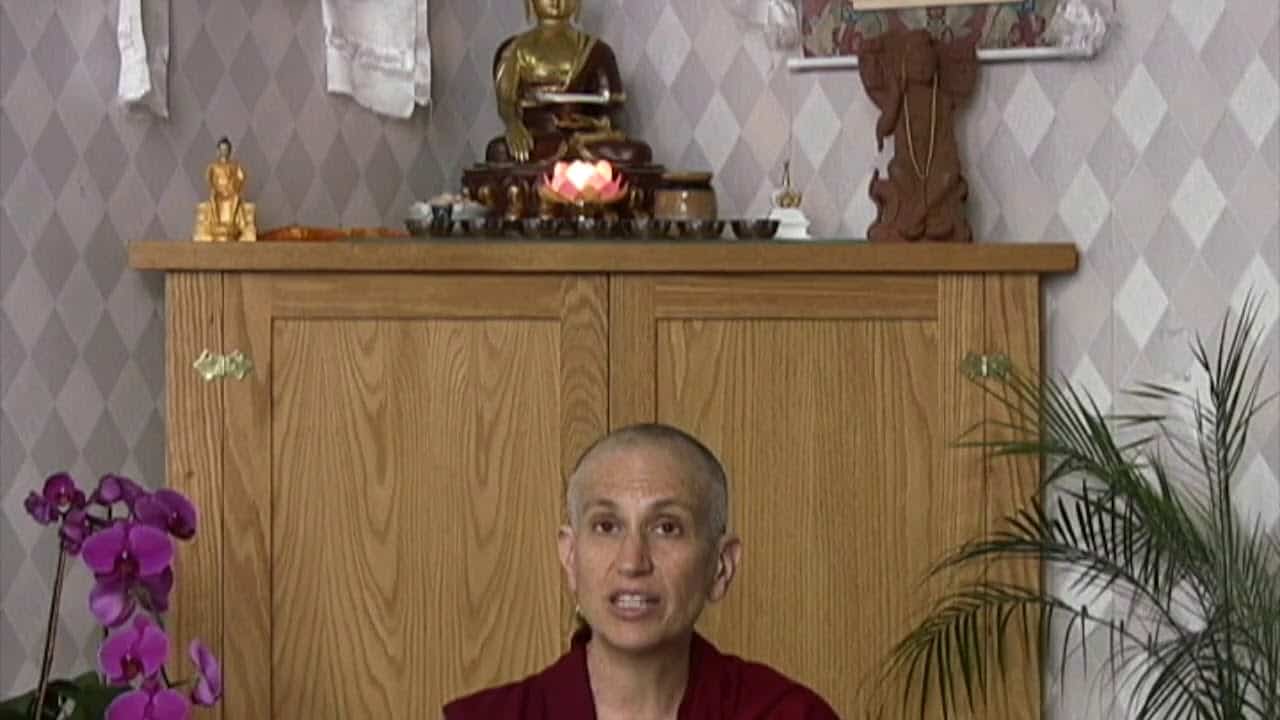

Venerable Thubten Semkye

Ven. Semkye was the Abbey's first lay resident, coming to help Venerable Chodron with the gardens and land management in the spring of 2004. She became the Abbey's third nun in 2007 and received bhikshuni ordination in Taiwan in 2010. She met Venerable Chodron at the Dharma Friendship Foundation in Seattle in 1996. She took refuge in 1999. When the land was acquired for the Abbey in 2003, Ven. Semye coordinated volunteers for the initial move-in and early remodeling. A founder of Friends of Sravasti Abbey, she accepted the position of chairperson to provide the Four Requisites for the monastic community. Realizing that was a difficult task to do from 350 miles away, she moved to the Abbey in spring of 2004. Although she didn't originally see ordination in her future, after the 2006 Chenrezig retreat when she spent half of her meditation time reflecting on death and impermanence, Ven. Semkye realized that ordaining would be the wisest, most compassionate use of her life. View pictures of her ordination. Ven. Semkye draws on her extensive experience in landscaping and horticulture to manage the Abbey's forests and gardens. She oversees "Offering Volunteer Service Weekends" during which volunteers help with construction, gardening, and forest stewardship.