The four thoughts that turn the mind

A talk hosted online by Innercraft in October 2023.

- What we have learned from our families and society

- Preciousness of our present human life

- Death and impermanence

- Karma, cause-and-effect on an ethical level

- Disadvantages of cyclic existence in samsara

Let’s think about why we’re here listening to the teachings. I think we obviously came because we want to learn something. So, what is it we want to learn and why do we want to learn it? There could be many reasons for why we want to learn something: it’s fun; it’s interesting; I get to meet other people when I do it; it’ll bring me money later on. There could be dozens and dozens of reasons.

But since this is a talk from a Buddhist perspective then we should have a motivation that has something to do with the Buddha’s motivation. When the Buddha was alive and taught, his motivation was always to be of benefit to the hearers. In other words, whoever was there, may they benefit. And not just benefit in terms of having a good time, and having wealth, and good health, and social status, and such, but he was always thinking of ultimate benefit—of how to really get people to look deeply at what human life is about, what the potential is, what are the actual causes of suffering and what are the causes of happiness.

He wanted them to think seriously about this, and then to be able to integrate what they learned into their life so that they could bring more peace into their minds and in the minds of the people around them, and also so they could make a positive contribution to society. With that kind of motivation—of caring about others and seeing ourselves not as isolated individuals but as members of sentient life that are all dependent on each other—with that kind of background, that kind of perspective, let’s listen and share together today.

How do we want to direct our mind

Today, we are going to talk about the four attitudes that change the mind. This is a very common, very popular teaching in the Tibetan tradition. All the different types of Tibetan Buddhism all have this in their teachings in one way or another because it really sets the stage for what we want to do in our lives and what the spiritual practice is about.

So, these are four thoughts to change the mind or to direct the mind. What do we want to direct the mind to? How to be famous? How to cheat more people? How to promise one thing and renege on our promises? What is it that we’re trying to direct the mind to? Like I said in the initial motivation, it’s important to really be able to think about what are the actual causes of happiness and causes of suffering, and what is our life and our potential?

Because we’re born in families, and our families teach us different things, and the society around us teaches us different things. When we’re little kids we don’t have the opportunity to really think about everything we are told; we just believe it in one way or another. I think one of the nice things about being an adult is that if we’re smart, we can take out some of those things that we’ve been believing for 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 80 years and really ask ourselves, “Are these true? Are they accurate? How much do I want these different things that I’ve learned to influence my life and the way I live?”

For example, many of us may have learned through the example of our parents about how to handle conflict: you handle conflict by yelling and screaming and throwing things. And others of us may have learned from our family that you handle conflict by everybody going to their own rooms and not talking about it. That is just an example. We just thought, as kids, that this is what the adults are doing so that’s how you do things, but if we really stop to look at our life, yelling, screaming, and throwing things actually doesn’t solve the problem that we have with the other person. Going to our own rooms and slamming the door also doesn’t solve the problem. And yet, we just get in the habit of doing things like this. This is a time to really start looking at some of those things and asking, “Do we want to perpetuate them or not?”

These are the four thoughts to change the mind. We only have an hour, so I’ll only be able to go through them very briefly. The first one is the preciousness of our present human life. The second one is death and impermanence. The third one is karma: cause and effect on an ethical level. And the fourth one is the disadvantages of cyclic existence—of samsara.

Rebirth and our precious human life

We start with having a precious human life. Now, what’s interesting in teaching this to people who are new to Buddhism is, if you were like me, I didn’t believe in rebirth when I came. It wasn’t that I didn’t believe in it; it’s just that nobody around me believed in it. There was the idea of heaven and hell, but none of that made much sense to me. Yet, all four of these thoughts that shift the mind are based on an understanding of rebirth, and an understanding of what our body and mind are, and how what we call I, or self, is just something that’s just designated in dependence on the temporary association of this body and this mental continuum. But most of us don’t come to Buddhism thinking like that.

We can get some feeling for the meditation on precious human life as newcomers to Buddhism, but I think the feeling for it really comes after you have faith in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and after you have some awareness of why, or how, rebirth works and some of the proofs that rebirth exists. Then you really begin to appreciate your present life because you have an idea of all the other things you could be born as, and you’re kind of glad you weren’t.

Some of the things to look at with this meditation is just to look at the good opportunity we have with this particular life. To just start out with, we have food and clothing and medicine and shelter. That’s a big thing that we often don’t even appreciate. We just assume it’s going to be there, but if you’ve spent any time traveling anywhere, including our own country, we see that not everybody has those four requisites for life. Many people are hungry; many people—between poverty, earthquakes, floods, wars and so on—don’t have a stable place to live. Again, because of those things, they may not have clothing sufficient for the climate or medicine when they get sick. So, it’s helpful to look at the fact that in our lives we have those and appreciate that opportunity, not just because we don’t have the pain of lacking those, but because they establish a basis upon which we can be curious about life. They establish a basis in which we can learn new things and think about them, evaluate our mental state, look at our habits, and decide what kind of person we want to be. Without those things being stable in your life, we’re just too busy trying to stay alive to think about other philosophical or spiritual matters.

And then many people have those four requisites for life, but they don’t have any interest in spiritual matters. They may pray to God when there’s some problem in their lives, but they don’t really question, “What is God, and what can God do, and does God exist? What’s my role in all this?” Because they’re just not interested in it. It could be many of our families. I know my family, in particular, both parents were children of immigrants, and they had no interest in spiritual things. Their goal in life was to get the American dream. That’s what was meaningful for them coming over here impoverished as refugees. Okay, that’s fine; you can’t talk somebody into having interest in that if they don’t. It’s kind of curious, I think, that they had a daughter like me who is interested and then my brother and sister who are not interested in spiritual things. What comes from your family? What comes from your previous life?

Open-mindedness and curiosity

That part of us that is interested in spiritual matters is a very precious part of us—ourselves. That mind that is interested has to be a mind of curiosity. It can’t be a mind of, “Just tell me the truth. Tell me what to do. Tell me what to believe; tell me what not to believe. I’ll do it, and if that’s the pathway to happiness, good enough.” To really be a spiritual aspirant, you have to have curiosity. You have to question. You have to challenge things. You have to think deeply about them. “How in the world does this work? Is it true?” We have that kind of curiosity; we should respect that trait in ourselves. It’s not only being curious, but being eager to learn, and when we do learn, being very open-minded and not biased.

If you really want to investigate the nature of life, you’ve got to be open to really think deeply about these things. And if you already have a bunch of fixed ideas about what the universe is, and creation, and heaven and hell, and good and bad—if your mind is really fixed, it becomes very difficult to learn. I think all of us here must have some kind of openness, otherwise we wouldn’t be here listening to this talk. We need open-mindedness, eagerness, curiosity, and intelligence. Once we learn and we’re open-minded, we need to be intelligent and really investigate what we learn—really go deeply and investigate in an intelligent way. Again, it’s not just believing, “Oh, the Dalai Lama said this so it must be true,” or “My teacher said it,” or “It’s written in some book so it must be true.” We have to really learn.

And the Buddha himself said this. He didn’t say, “Oh, just go read all the sutras that I spoke and believe everything because I’m enlightened.” He said, “I’ll teach you and then you have to go think about it and see what makes sense to you.” We should value those qualities in ourselves that we have now to be eager, to be inquisitive, to be intelligent, and to be open-minded, to have some commitment to this journey. It’s not just, “I’ll do it because my friends are doing it,” or “After I make a million bucks then I don’t need it anymore,” or whatever our thing is.

More than just external circumstances

We should really respect that part of us that has these qualities and the part of us that is genuinely sincere in looking for the truth, or the truths, or the way things work. That’s just a little bit about our precious human life. And I think it’s important to really respect ourselves in that way. Also, it isn’t sufficient to have good external circumstances—when we have the necessities of life and to have a mind that is curious and intelligent and so forth—but we have to have access to the teachings also. Many people do not have access to the teachings. Or they live in a country like Tibet, China, Vietnam, and so forth, where they used to have access to the teachings—plentiful access—and then the country became communist and religion was suppressed. The clergy was prosecuted, or made to disrobe, or imprisoned, and books were burned. Even if you had that curiosity there was no place you could go to learn.

One of my friends used to travel and teach behind the Iron Curtain in the communist countries before 1990 when everything fell apart. And I also went to Prague later to the same place that I’m going to tell you the story about. He told me that when he was teaching in Prague, Czechoslovakia when it was communist, that it was held at someone’s home because you couldn’t have a spiritual meeting. You couldn’t advertise it and have it at a church or whatever. Everybody had to come separately. You couldn’t have two or three or five people come at the same time to the same person’s home. So, everybody had to come at different times. The home had two rooms; there was a living room in front and there was a bedroom in back. In the living room they set-up a round table with a card game, and they had dealt out cards, and they had soft drinks and everything you have when you get together with your friends to play cards. That was all set-up. Then they went in the bedroom and had the teaching. Why? It was in case the police came. They would hear the police at the door, and they could run from the bedroom out to the living room, sit down, and pretend to be playing cards so the police didn’t know they were having a Buddhist talk.

Imagine for a minute living under that kind of fear just for wanting to explore spirituality. This happens all over the world. And there is the threat of that happening here in the US now with some people who are strongly thinking that this is a country with one religion, and it’s their religion, and that everybody should believe. That’s quite dangerous because when you think about it, every country on this planet has more than one population in it. There is no completely homogenous country anymore. Everybody has populations of different cultures, different religions, and so on. But some countries try to make it all one: “It’s my way.” We’re very fortunate that—at least so far—we don’t live in that kind of thing. We have to be very conscious, though, and protect our freedom. Okay, so that’s precious human life.

Making use of our good opportunity

The second thought that turns the mind is death and impermanence. In other words, we have this precious opportunity, we have so many qualities external and internal going for us, but how long are we going to live? And how long even in this life, if we live a long life, will we even have those qualities? You can start out life with wealth and then you’re impoverished. Things change and can change very, very quickly like that. You start out with good health and even as a young person you can get very severely ill. The idea is that we have a good opportunity now, so let’s make use of it. And what is making use of it? It’s really looking at what is valuable in our life, because most people and most societies function around what we call the eight worldly concerns, which are four pairs.

The first pair is delight in having material wealth and despondency when you don’t have that or lose it. Then the second pair is delight in having people’s praise and people’s approval and then so much internal conflict if people criticize us or don’t approve of us. Then we think, “What am I worth? Nothing. Something’s wrong with me.” The third pair is delight in having a good reputation and despondency when we have a bad reputation. This is different than the praise and approval one. Praise and approval is more on a personal level: people like you, they praise you, they approve of what you’re doing. Reputation is what a big group of people think about you. That group of people could be your whole family, your extended family, your workplace. It could be your religious place, or it could be your bowling club, your golf club, your tennis club. It could be all your be all your poker friends. It could be all the people you get together with to figure out how to invest your billions of dollars. It’s a group of people.

This is what the lives of movie stars, and athletes, and politicians, and business people revolve around. “If I have a good reputation and many people know how wonderful I am, then I am successful. If people find out about all the corrupt things I’m doing, and I get arrested and prosecuted and have a bad reputation, that’s horrible. I don’t want that.” As we all know, it’s a witch-hunt. Not just one person has a witch-hunt. Whenever people criticize us or tear down our reputation, we say, “I didn’t do that.” I don’t think people say, “Yeah, I got found-out. I did that.” It’s always: “Me? Me? Oh, no.” Isn’t it? Even living here in a monastery, if someone says, “You didn’t show up and you were on dishes today,” we say, “Oh, no, I did show up, but they told me that I wasn’t needed there.” Or we might say, “Actually, it wasn’t my name on the schedule; it was somebody else’s name.” There is always some reason, isn’t there? Always. “You always blame me for not showing up for dishes. Why don’t you blame anybody else? This is a witch-hunt. You just want all the witches to do the dishes!” [laughter]

And then the last pair is so much attachment to sense pleasure objects and distaste for unpleasant sense objects. We want good food, to see beautiful things, to hear the kind of music we want to hear, to smell nice smells, to sleep in bed that is not too soft and not too hard in a room that is just the right temperature with our favorite blankie that is very soft and very nice and keeps us exactly as warm as we want to be kept—not too warm so that we sweat when we sleep, but not making us cold either. Everything for my physical pleasure has got to be perfect. Perfect means it is what I want it to be; that’s the definition of perfect. And, boy, when we don’t get that, we let the world know: “This food stinks, take it back,” “I’m meditating, and it’s too noisy,” “I can’t stand the smell in here; somebody burnt something.” And it goes on, and on, and on. “My shoes hurt. Everything hurts.” Anyway, you know the story.

Clinging to temporary things

Our life gets very focused on these four pairs of delight and despondency, yet do any of those things that we delight over or get despondent over come with us when we die? Somebody just wrote to me recently saying they want to move to a place that they really like, but they can’t take their BMW, so should they stay where they are and have the car longer or sell the car and go to where they really want to live? This is big suffering having to make this decision. But when you die, is your BMW going to come with you? You’re not even going to ride in it to the funeral place; they put you in some black car in some box. What are you going to do? Are you going to knock on your casket and say, “Take me out of this box, I want to ride in my BMW to my own funeral”?

We get so wigged out about things that are inconsequential, that no longer matter sometimes even the next day, or the next week, or the next month. We fuss about them so much, and we can’t take any of them with us when we die. We might think, “Oh, but I’ll take my reputation with me.” Well, that’s great. You’re going to be born into another body in another realm in another world, and you’re not even going to be around to read your own obituary and see your own funeral with everybody crying at it. “Finally, they realized how much they love me, and they’re sobbing at my funeral.” Sorry, we aren’t going to be around. Even if they drive you to your funeral in your own BMW, you’re not going to be around to see it because the body and the mind have separated. The mind has gone on to the next life, the body is vegetable material—that’s it!

Really think about what matters in life: How important is my reputation? How important is it that everybody thinks I’m a wonderful person and approves of me and praises me? That’s often our number one wish: “I just want to be liked by everybody; nobody has permission to not like me because I’m wonderful.” Is that really the purpose of our life, especially when we consider that things are changing all the time?

Think about how long you can spend fussing over your hair. And for the guys, sometimes trying to get hair. And fussing over your body shape: “Oh, I don’t look like the people in the magazines.” Think about how long we spend fussing and our whole self-esteem involved in trying to look like those people. You want to look like Rambo. I know, he’s old. [laughter] Who are the new ones? Arnold Schwarzenegger is still around, but he’s old too! [laughter] Maybe Ken—we all want to look like Barbie and Ken or have everybody praise us. Anyway, we are all getting older and uglier. All the people who everybody wanted to look like when I was young—none of them look like that anymore, and people just laugh when we say their names. [laughter] Marilyn Monroe, I think she still has something.

Audience: She died young enough.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Yeah, she died young enough, and from an overdose. Great way to die, huh? I’m being facetious. But everybody wants to look like Beyoncé. Don’t you want to come out in the room with hardly anything on, but whatever is on is glittering like mad? [laughter] And the lights are flashing all over and you think, “Now I’m important; I look like Beyoncé.” [laughter] And you have a voice like hers. But this is what some people set for their goal in their life. Can you take any of that with you? So, it’s important to think about impermanence and, given that things are changing all the time, what’s really important?

These things that we fret about are not so important. And even if you have problems, they will get resolved. You don’t even take your problems with you to your next life. Somebody’s suing you; they don’t come in your next life. Somebody’s writing bad things in the newspaper about you; they don’t come with. So, really think about it: given that everything ages and changes and that what we have we are going to separate from and there’s no way around it, what’s important?

What really matters

From a Buddhist viewpoint what’s important is these four thoughts that change the mind, plus the rest of the path. Because our virtue, our good karma, that comes with us in our next life. That will influence where we’re born, what we’re reborn as, if we have the same conditions for practice that we have now, or if we don’t. Our actions now create karma that are like the seeds, or the potentials, left by the actions that we do, and our actions have an ethical dimension to them. What we do matters, what we say matters, what we think matters because it all leaves imprints on our own mind that will influence what we become in our future lives. And everything we think and say and do also influences the people around us and the world around us.

What we want to take with us is our virtuous qualities and our ability to really give something positive to the world. We don’t have to be famous to do that. We do that by having a kind heart and being kind to the people we live with. Imagine if everybody did that; it would be amazing. For those of you who know what’s going on in Congress these days—or I should say what’s not going on in Congress—there is no Speaker of the House. Congress is, like, stuck. But are those people thinking, “I want to create virtue to be of benefit to society and to have a good rebirth where I can really continue along the path to awakening”? Are they thinking about that? No, they’re all thinking about their parking space in the Capitol. And they want to be re-elected so they can continue to have that parking space, or so they can be on TV or on the internet or wherever, with a whole bunch of people around them holding out tape recorders to catch their every word about how awful the other side is. Is that how we want to spend our lives? Think about it. No.

Put it this way: when I was quite young, a friend said to me, “In life, I want to solve more problems than I create.” At that time, I had no idea about the Dharma, the meaning of life, or anything like that, but I thought, “Oh, that sounds good; that makes sense. Can I solve more problems than I create?” That all revolves around karma, the third of the four thoughts that change the mind—thinking about what we do and why we do it.

The Buddha laid out a list of ten things to try to avoid doing because usually when we do these ones we have a horrible motivation. We cause turbulence and chaos in our relationships with other people. And we put imprints in our own mind for suffering in the future. In other words, when we harm others, we are also harming ourselves. We often think, “If they get harmed, then I win. I’m safe. If I can harm my enemies, then that benefits me.” But when you have knowledge of karma, having animosity and wanting to kill our enemies, aside from not solving the problem, also puts the dispositions on our own mindstream to have suffering in the future. So, why do that? Why do that? It’s so ridiculous. Why do we do it? It’s because our mind is overwhelmed by afflictions very often.

Sometimes we know we’re going to meet with somebody that triggers us, so we go into the situation with a strong determination: “I am not going to bite the hook. They may throw out the hook to try to trigger me, but I’m not going to bite it. What they’re saying doesn’t really have anything to do with me. It has everything to do with their mental state, their suffering. There is no reason for me to be angry and upset with them.” We have that determination even before we go into that situation. But then we go into the situation, and the person says exactly what pushes our buttons, and we explode: “Why are you saying that to me? Why are you doing this? Rahgggg, rahggg, rahggg!” So, what happened? We came in with this wonderful motivation, but what happened is that our afflictions are strong. It was our mental afflictions—predominately ignorance, anger, and clinging attachment, but with a little bit of jealousy and some arrogance thrown in, and some laziness and some deceit and pretense. There are lots of afflictions. Those just get the best of us. And so this is about learning to really stop and think about our actions. Learning to refrain from things that are detrimental to others and ourselves. That is the start of creating the cause for happiness, not only for ourselves but for others.

I look at what’s going on in our world with the war between Russia and Ukraine, and it’s so painful for me to even consider that war is happening and that so many people are getting killed by strangers they don’t know, and they are also killing strangers they don’t know. And for what purpose? What is the purpose? I don’t see any purpose. So, it’s easy to look and see what others are doing as troublesome, but it’s harder to look at what we do as troublesome. We may not fight a war and kill people, but we’ll certainly talk about them behind their backs and ruin their reputation, won’t we? If we don’t like somebody, we think, “I’ll just tell the whole world about how mean they are and what they did to me, and I’ll just embellish the story a little bit to really bring the point home about how evil they are and how they’re the cause of all my suffering.”

We have to really begin to do something with these afflictive mental states that are not part of who we are. They are not permanent, inherently existent parts of our mind that always are there. Anger isn’t the only way we can possibly respond to harm. There are many ways to respond. It’s important to think about these, and to think about the karma, and to be able to identify what our triggers are—where we really go bananas. And then we can learn the antidotes to those triggers: how to direct the mind, what to think about to calm our anger, to calm our greed and our attachment, to get rid of the ignorance that obscures us. We can begin to throw some water on our arrogance.

Those were the first three thoughts to change the mind: precious human life, death and impermanence, and karma. It’s really considering that what we think, what we say, and what we do matters. We are one person. In terms of being one person, we cannot change the whole world either one way or the other, but we can do a lot one way or the other. So, how do we want to direct our lives?

Our karma influences our rebirth

Then the fourth of the four thoughts that change the mind is the defects of cyclic existence. We can think about those first three—precious human life, death and impermanence, and karma—in terms of this life. When we come to thinking about the defects in cyclic existence, we’re thinking not only about this life, but just about the fact that we are reborn again, and again, and again, and we are not choosing our rebirths. We don’t have control over our rebirths, but we are born by the force of our karma. It’s not this thing where we sit up on some cloud there and look down and say, “Well, who is going to be privileged enough to be my parents in this life? Put your applications here, and I’ll go through them and pick my parents.” No. It doesn’t work like that. The force of the ethical or unethical actions we’ve done makes us attracted towards one rebirth or another. And it doesn’t just happen once; it happens again, and again, and again, and again. And we’re not always born as humans. We can be born as other life forms.

For those of you who haven’t been to the Abbey, we have four cats. Their names are Love, Compassion, Joy, and Equanimity. That’s a good way to start your life off, with names like that. But they’re cats, so they’re missing this element of human intelligence. We try to tell them, “Don’t chase the gophers. Don’t kill the mice or even the stink bugs. Don’t kill any other being.” And our cats just look at us like, “Feed me. What are you talking about?” [laughter] But on the other hand, our cats live in a Buddhist monastery. That’s pretty difficult, to live in a Buddhist monastery. There are not so many people who live like that on this planet. And yesterday His Holiness the Dalai Lama gave some important teachings and empowerments and so on, and Venerable Damcho wrote to me that our cat, Mudita, Miss Joy, slept on her lap the whole time. Maitri, Miss Love, slept on the cushion of the recliner next to my computer the whole time. They had a lot of good imprints put on their mind. Did they appreciate it? Well, a good lap is comfortable enough, and a good recliner, good cushions. [laughter] That’s her recliner, by the way, I seldom sit in it. How much of a chance do they have to create virtue? It’s pretty difficult. We have this saying in English: “Ignorance is bliss.” But that one is not true.

How ignorance causes suffering

The kind of ignorance that we talk about in Buddhism is the ignorance of the nature of reality, and if you don’t know the nature of reality, and if you don’t understand cause and effect very well, and if your mind is overwhelmed by anger, ignorance, and attachment, then it is pretty difficult. It’s like being on a Merry-Go-Round. You’re on your little horsey, and your horsey goes up, and it goes down, up and down, and you keep going around and around on the Merry-Go-Round. Remember that? If Mom and Dad had put you on that Merry-go-Round and then purchased unlimited tickets so that you were on that Merry-Go-Round for the next 24 hours, is it still going to be fun? We’d think, “Get me off this thing! I’m going up and down, and my tummy hurts. I gotta go pee. I’m sick of looking at the same horsey all day long!” [laughter] “I want someone else’s horse. I want something else—something new, something exciting.” But you’re just on the same Merry-Go-Round, and you can’t get off.

It’s because at first you don’t really want off, until you’re on too long, and because you’re attached to different things on the Merry-Go-Round. One part of your mind says, “My horsey’s the best horsey; I don’t want to separate from it. My horsey’s better than yours.” But when you really think about it, is it worth it to keep going around and around like that?

Here is where we start to think about liberation. Because there exists a state of liberation—it’s called nirvana—where you have realized the nature of reality and where you are no longer reborn under the force of mental afflictions and the karma that is supported by ignorance. And we’re not only seeking nirvana, liberation, but seeking a state of awakening—full awakening or full enlightenment that is beyond that—where every single defilement in the mind has been banished, every single good quality has been developed, and where we really, really, really can have a lot of compassion and wisdom empowered to be able to benefit other living beings. And so we develop that aspiration to become a fully awakened Buddha. Then with that aspiration, or even if you’re striving for nirvana, liberation, then you’re going to really be quite mindful of how you live your life because you’re aware that whatever you’re doing now is creating the cause for what you’re going to be. And you also care about other living beings, and you want to bring more happiness than problems to them.

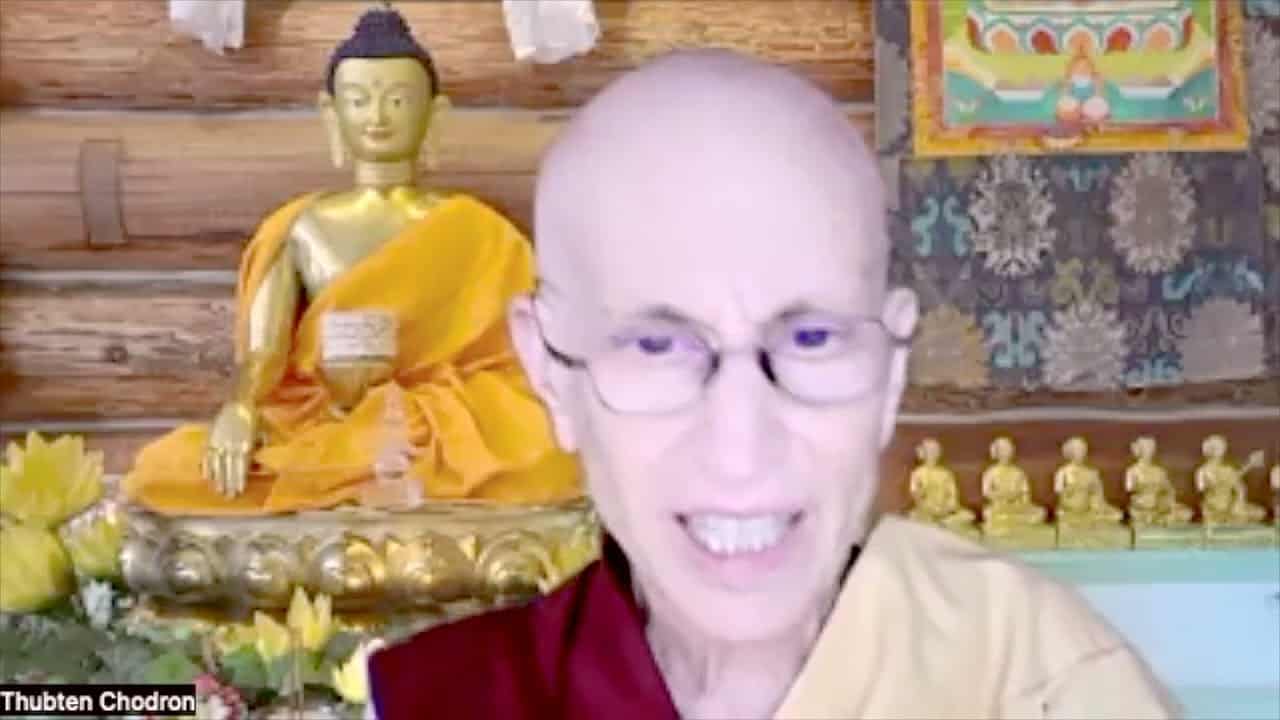

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.