The Three Jewels as ideals

- Teachings on taking refuge

- Distinguishing features of the three jewels

- Guidelines on how to practice

- Understanding the benefits of the precepts

Refuge teaching (download)

We’re going to talk a little bit about refuge today—specifically taking refuge by knowing the distinguishing features of the Three Jewels; and taking refuge by accepting the three objects of refuge as ideal, taking refuge by not speaking in favor of other refuges, and also some of the guidelines once you’ve taken refuge. (The guidelines to help you keep your refuge and deepen your refuge.)

The distinguishing features of the Three Jewels

First to start with taking refuge by knowing the distinguishing features of the Three Jewels. Our old friend, Joe Blow, helps out here. He says, “Each of the Three Jewels has so many qualities, is it sufficient to take refuge in only one?” Like, “Can I bargain?” The answer is, “No.” We need to take refuge in all three because there are differences in various aspects.

1. Characteristics

First of all they have different characteristics. The Buddha is the one who’s abandoned all defects and developed all good qualities. He can see the two truths simultaneously because he’s omniscient. The Dharma is the true paths and true cessations that the Buddha taught to meet sentient beings needs; and teaching the Dharma is the reason the Buddha appeared in the world. The Sangha are those who have realized the Dharma directly, in other words, who have direct realization of emptiness. They can give us guidance so that we can do the same. They prove the validity and usefulness of everything the Buddha taught—because the Sangha has actualized it by following the Dharma that the Buddha taught. It shows that the whole system works. That was the difference in their characteristics. You can see because they have those different characteristics why you have to take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha—that just one won’t work.

2. Enlightening Influence

They also are different in terms of their enlightening influence. The Buddha gives the transmitted and realizational Dharma. The transmitted Dharma is what’s passed down by teaching. Realizational Dharma is what we realize in our own mind. In other words, the Buddha says what to practice and what to abandon. That’s the main thing he teaches. He transmits the Dharma in the most effective way to us. The Dharma eliminates the afflictions and sufferings. And the Sangha gives us encouragement and inspiration and assistance when we practice. Also by taking refuge in the Sangha we know that we are not alone. Because of their differences, their enlightening influence, they influence us in a positive way then we need to take refuge in all three.

3. Aspiration and Regard

They are also different in terms of the aspirations or the kind of devotion or fervent regard that we have for each of the three. In terms of the Buddha, we aspire to make offerings, we have devotion and respect. We show respect for the Buddhas help and for the teachings by offering and being of service and practicing and so on. In terms of the Dharma, we aspire to put it into practice and transform our minds into the Dharma. That’s how we show our high regard for the Dharma. For the Buddha we show high regard by more devotional types of things; and for the Dharma by transforming our minds. For the Sangha we show our regard by practicing together with them and joining in their efforts to sustain the Dharma for future generations.

4. Practice Relationship

The fourth distinction is that the Three Jewels are different in terms of how we practice in relationship to the three of them. The Buddha is our role model of what we want to become. We make offerings, do prostrations, and show respect to create the merit to become the Buddha. That’s how we practice in relationship to the Buddha. In relationship to the Dharma, we learn it, we practice it, we meditate on it. We integrate it with our body, speech, and mind. In terms of the Sangha, we practice with it by practicing harmoniously together with the Sangha, sharing the teachings, and by the Sangha community sharing their material possessions. We also do this by following the example of the Sangha Jewel. Again, these are the differences of how we practice in relationship to the Three Jewels.

5. Qualities

Then the fifth difference or distinction is what qualities to remember, or what qualities to be mindful of, in these three. In terms of the Buddha, we are mindful or remember that he is free from the three poisonous minds, and that he has wisdom, compassion, omniscient mind, and the capability to lead us to enlightenment. The Dharma has good results in the beginning, middle, and end. When we practice it, that quality that we are mindful of is the goodness of the Dharma. With the Sangha, the good quality to remember is that they are on the right path. They are impartial so that they’re true friends. They are objects of respect who can provide companionship to us on the path. The Sangha Jewel, like the Buddha, isn’t going to play favorites and help one and not help the other, and so on.

6. Creation of Merit

The sixth difference in terms of the Three Jewels is how we create merit in terms of each of them. In terms of the Buddha, we create merit again by offering and prostrating to the Buddha—these kinds of more devotional things. To the Dharma, we gain merit by putting it into practice in our own mind. The Sangha, we create merit by doing virtuous activities together with them and by making offerings to them, and by offering them respect. You can see when you go to a big teaching and you have many practitioners around you, you feel very inspired. Think about if they were all the Sangha Jewel who had realized emptiness. The way you practiced with them would be quite magnetic, magnetizing.

Accepting the three objects of refuge as ideals

The next outline is: “Taking refuge through accepting the three objects of refuge as ideals.” We should meditate on all these three. It’s good to go through all these outlines and meditate and make examples so that we really understand how to relate to the Three Jewels—how to actually take refuge in our mind. We talk a lot about refuge, but if we really meditate on this it will show us how to do it.

Accept them as ideals first in regards to the Buddha. By accepting the Buddha as the ideal teacher, then we look at the Buddha as the doctor. By accepting the Dharma as the ideal refuge, the Dharma becomes what will actually free us—in other words, the medicine. By accepting the Sangha as ideal friends for helping us realize the path, we relate to the Sangha as the nurses. That’s one way of talking about how to accept the Three Jewels as objects of refuge as ideal.

Another way is to see the Buddha as the ideal that we will definitely attain. Our ultimate role model and Buddhahood is what we aim for. Next is to see the Dharma as definitely being the ideal method to actualize full awakening. Third is to see the Sangha as the definite companions who will help us on the path—the companions we can rely on and trust.

Not speaking in favor of other refuges

The next outline is: “Taking refuge by not speaking in favor of other refuges.” In other words, keeping your refuge clean-clear on the Buddha, Dharma, Sangha without going, “Well, maybe this, maybe that, maybe the other thing.” If you have indecisive wavering about refuge, you won’t get anywhere in your practice. You can see why. If you don’t know who your guides are, how are you going to get anywhere by practicing their guidance? If you’re not sure, if you have a lot of doubts about who your guides are, like, “Maybe I should practice another religion, that guide seems better.”

We have to really try and develop certainty through the qualities and functions of the Three Jewels. To dispel this kind of doubt, we can also learn about the founders of other doctrines and their teachings and their disciples. We look at the founder, their dharma teachings, their community around them, and then see the difference between these and the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Since many of us have grown up in other religions, it can be very helpful to think about the founder of that religion and what the teachings were. What the path was, how the path was laid out, and then the community around it and how they were and how they practiced. Through that we can see why the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha is a supreme refuge.

In one way, you can look at the four noble truths of any religion. If you take a theistic religion, how do they define dukkha? What’s unsatisfactory? What do they say is the cause of it? Is it Adam and Eve? What is the ultimate goal you’re aiming for? What’s the cessation of that suffering? How do you get there? What path does that religion say? Does it propitiate an external being? What is it?

While in general we do not go about learning other religions, if we already know what we want to believe in, we want to concentrate on that. Sometimes, it can be helpful to learn this stuff and really think about it. It helps us to see the excellent qualities of the Three Jewels that are our objects of refuge. We may find that other founders of religions or teachers are jealous, they want offerings, they want reputations, they’re going to judge you if you don’t pay them homage or if you don’t believe in them, or something. Some other teachings require severe asceticism and so they don’t really lead to liberation because you’re too busy torturing the body. The Buddhadharma’s Four Seals—they’re backed by logic and analysis, not by faith without investigation. That’s a real quality of the Dharma that we can rely on.

Some followers of other faiths, they’re very elitist or they’re full of desire or saying, “We’re the supreme people”—or the supreme whatever. And they don’t want to let other people in. Whereas the Sangha is impartial and compassionate, it doesn’t harm others at all. You look at the qualities of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha and it helps you really to appreciate them, to take refuge in them, and to know how to relate to them.

Taking formal refuge in a ceremony

When you have really thought about the qualities of the Three Jewels, when you know these qualities, then you know these different distinctions in the Three Jewels and how to relate to them. Then you may want to take refuge officially and you do that by requesting a teacher to do the refuge ceremony for you. At the time you take refuge, you can also take the five precepts. Some teachers say you have to take at least one precept, some teachers say you don’t have to take any precepts when you take refuge, some say you have to take all five—so you have to check it out.

Actually, the refuge that we do in front of the teacher is a more public statement of what is going on in our heart, but that is like beginning the deepening of refuge because the real refuge occurs in our heart. It deepens as we continue to practice. I always say refuge isn’t an on and off light switch, it’s one of the turning ones that gets brighter and brighter as we practice. Doing the ceremony is a way to connect you to the lineage of practitioners. Some people don’t like ceremonies. You don’t need to take the official ceremony if you don’t want to, but some people like to because it gives you this feeling of being connected to a whole bunch of human beings who actually practice what you’re starting out practicing, and who achieved very good results and high realizations from doing that. Taking refuge in that way really gives you a lot of confidence and inspiration in your practice.

Once you’ve taken refuge, there are different guidelines that help you to keep your refuge. They help you develop it and deepen it instead of just saying “I take refuge,” and then the next day forgetting all about it and going about doing things the same old way, digging yourself the same old holes.

Guidelines for refuge—from Asaṅga

This first set of guidelines comes from one of Asaṅga’s texts, Compendium of Determination. There are eight points here:

1. First, in analogy to taking refuge in the Buddha:

Commit yourself wholeheartedly to a qualified spiritual mentor.

When you first take refuge in a ceremony, you may not yet have the feeling of somebody being one of your spiritual mentors. In actual fact, the person giving you the refuge ceremony becomes one of your spiritual mentors, but you may not feel that connection at that time. It could be that later on you meet another teacher that you have more sync with. Then that person becomes your main teacher. That’s fine. There’s no pressure to find a teacher right away and commit yourself to a teacher. It’s much better to go about things slowly, examine people’s qualities, see if they’re teaching accurately. See if you have the karma with them so that you feel inspired by how they practice and you feel admiration in them. Go slowly in finding spiritual mentors.

2. Second, in analogy in taking refuge in the Dharma what we should do is:

Listen to and practice the teachings as well as put them into practice in our daily life.

That’s real clear. If you’re not going to do that then you don’t really need to take refuge.

3. Third, in analogy to taking refuge to the Sangha:

Respect the Sangha as your spiritual companions and follow the good examples that they set.

Now, here we have to talk about the meaning of the word Sangha. The Sangha that we take refuge in is the Sangha Jewel. Those people, individuals who can be either monastics or lay followers, who have direct realization of emptiness. They are the Sangha Jewel that we take refuge in.

The representation of the Sangha Jewel is a community of four or more fully ordained monks or nuns. Not novices, not lay people, but fully ordained people because they are keeping the precepts. They have committed their whole life to it. They are the representative of the Sangha Jewel. Nowadays, in the West, people often use the term Sangha to refer to anyone who comes to a Buddhist center. This is not the traditional use. His Holiness the Dalai Lama does not use the word this way. I’ve see times where people will ask His Holiness the question about the Sangha, referring to just anybody who may or may not be a Buddhist, and His Holiness gives the answer thinking of the Sangha community, the monastic community.

The reason I don’t advocate calling everybody at a Buddhist center, or even the whole community at a Buddhist center, the Sangha is because not everybody at the center or who comes to a temple may know the Dharma or may even consider themselves a Buddhist. Some of the people may or may not keep good ethical conduct because they may or may not have precepts. It becomes confusing when you hear, “Take refuge in the Sangha.” You look around and there’s Joe Blow who has an alcohol problem, there’s Suzy who’s sleeping with somebody else, and there are a couple of other people from the center who are fighting with each other. Then you say, “I take refuge in these people and they’re going to lead me to enlightenment?” It just doesn’t work. When we think of taking refuge or following a good example we have to really look—at a minimum, at people who are keeping good ethical conduct. I think to avoid that kind of confusion we should use the term Sangha for the monastic community and use just Buddhist community to refer to the people in the Dharma center.

Here, it is talking about the monastic Sangha and to see them as your spiritual companions and follow the good examples that they set. I want to emphasize “good examples.” Monastics—we’re human beings with defilements. Sometimes we goof, sometimes we don’t act properly. Do not follow the Sangha’s “bad examples.” We have to really be careful about this because sometimes we’ll hear stories about how other people practice, even great practitioners, and we’ll think, “Great, I should practice exactly like them.”

We might hear about Milarepa, for example, who went up into the mountains and ate nettles, and wore hardly anything, and meditated all the time. We think, “Okay, I’m a brand new Buddhist. I’m going to follow Milarepa’s example and do that.” Well, no, you’re not ready to, unless you have some really extraordinary karma from a previous life. Although Milarepa is definitely part of the Sangha Jewel because he has realizations, and that’s definitely a good example that he is showing, we also need to see, “I’m not capable of doing what Milarepa’s doing. I shouldn’t really try to emulate him at this particular time in my practice.” On the other hand, if you see somebody who may be a teacher,…well, there’s no certification process for someone becoming a teacher in Buddhism. Basically, if there are people who follow you, you become a teacher. There may be somebody who has people following them who does not behave very well. You shouldn’t say, “Well, that person’s a student or they’re a monastic, or whatever it is, and they’re doing this and this and this, so that means that I can do it, too.” No. We always look at what the basic precepts are that the Buddha taught, and we always have to be real honest about what level we’re at and how we need to act—and so not to follow people’s bad examples. Also, not to think that we can follow their extremely good examples when we don’t have the qualifications to do so.

4. The fourth one is to:

Avoid being rough and arrogant, running after any desirable object you see, and criticizing anything that meets with your disapproval.

That one’s really hard, isn’t it? Avoid being rough and arrogant. “I’m a big know-it-all,” pushing people around, running after any desirable object we see. This is what we do all day, isn’t it? Criticizing anything that meets with our disapproval, “I don’t like this and I don’t like that, and why are they doing this? Why are they doing that?” So here it is—first step on the path of refuge guidelines—a pretty weighty thing to practice.

5. The next one is:

Be friendly and kind to others, and be concerned more with correcting your own faults than with pointing out those of others.

This is another hard one to keep. Be friendly and kind to others—“But I’m in a bad mood, I don’t want to be friendly and kind to them. They should be friendly and kind to me first.” Be more concerned with correcting your own faults than with pointing out those—“But why should I do that because this person does this, and this one doesn’t do what they’re supposed to, and that one’s always messing around, and that one doesn’t do their chores, and that one burps.” We’re always pointing out faults in other people, aren’t we? These last two are big, aren’t they?

6. The sixth one is:

As much as possible avoid the ten non-virtuous actions, and take and keep precepts.

It’s also hard to avoid the ten non-virtuous, isn’t it? That’s not so easy. When it says “take and keep precepts,” it’s referring to the one-day precepts or the eight Mahayana precepts, or the five lay precepts, or the monastic precepts, and so on. The reason this is a guideline is because if you keep the precepts, your practice goes better.

7. Seven is to:

Have a compassionate and sympathetic heart towards all other sentient beings.

Wow, that one’s also difficult, like—“They should have a compassionate and sympathetic heart towards me, shouldn’t they? Why should I have a kind heart towards them? They need to have a kind heart towards me first. Then I’ll have a kind heart towards them.” Right?

8. Number eight is:

Make special offerings to the Three Jewels on Buddhist festival days.

This can mean on the full and new moon to make offerings; or the four special holy days: the Day of Miracles, Vesak (the Buddha’s birth, day of enlightenment and passing away), the Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, and Lhabab Düchen (which is the day the Buddha descended from the god realm of the Thirty-three after teaching his mother the Dharma).

Guidelines in terms of each of the Three Jewels

There are guidelines in terms of each of the Three Jewels—how to practice in relation to each of the three. This comes from the oral tradition.

How to practice in relation to the Buddha

Having taken refuge in the Buddha, who has purified all defilements and developed all excellent qualities, do not turn for refuge to worldly deities who lack the capacity to guide you from all problems.

Don’t take refuge in a Judeo-Christian God, or in séance deities, or in spirits, or in oracles. These spirit beings, they may tell fortunes and do things like this, but their clairvoyance is not superior and they can be wrong. If you follow them, you can get really stuck. Really keep our refuge in the Buddha not in lesser spirits, or so on.

Respect all images of the Buddha: do not put them in low or dirty places, step over them, point your feet towards them, sell them to earn a living, or use them as collateral.

Think of all the Buddha statues or pictures, even if you’re storing something, you do not put it on the floor in the closet; always up higher or at least with something underneath it. You wrap it and you keep it clean. If you have an altar, then you keep it clean.

When you’re in the meditation hall and you need to stretch your legs, you stretch them to the side. People always go, “Well why? Why can’t I stretch my legs towards the Buddha?” The answer is because it’s disrespectful. They say, “Why is that disrespectful?” And I say, “If you go into a job interview, would you put your feet up on the desk of the person who is interviewing you and point the soles of your feet towards that person?” No. Then why would you sit in that position in relationship to the Buddha who is more important than a prospective employer?

When looking at various images, do not discriminate, “This Buddha is beautiful, but this one is not.”

You can talk about the artistry. This artistry is good, but this artistry is not so good. ‘Do not treat with respect expensive and impressive statues while neglecting those that are damaged or less costly.’ Similarly, don’t treat very expensive, gorgeous statues really well and then statues that may be damaged or not very costly, just brush them aside, and don’t treat them well. Don’t do that. This is a practice of mindfulness. From the side of the Buddha, Buddha doesn’t need us show respect and do these things. But from our side, we need to be mindful of how we relate to holy beings. These guidelines are in place because it helps our mind to pay attention and to cultivate proper respect.

How to practice in relation to the Dharma

Having taken refuge in the Dharma, avoid harming any living being with our body, speech, and mind.

This is the bottom line.

Also, respect the written words which describe the path to awakening by keeping the texts clean and in a high place. Avoid stepping over them, putting them on the floor, or throwing them in the rubbish when they are old. It’s best to burn or recycle old Dharma materials.

It’s the same with your Dharma texts. Keep them clean. Put them up high. Don’t put them on the shelf with your sci-fi books and your dime novels. Don’t leave your books hanging around and then put your coffee cup on top of it. Don’t even put your glasses and mala on top of it. Don’t put your Dharma books on the floor. People go, “Why not, it’s just paper?” I say, “Well, your paycheck is just paper, too. Would you put a full coffee cup that may be wet on the bottom on top of your paycheck? Would you put your paycheck in just any old dirty place? Would you step over your paycheck and say, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ and disregard it?” Why would we do that to the Dharma, the texts that describe the Dharma to us, considering that the Dharma is more important than our paycheck?

How to practice in relation to the Sangha

Having taken refuge in the Sangha, do not cultivate the friendship of people who criticize the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha or who have unruly behavior, or do many harmful actions. By becoming friendly with such people you may become influenced in the wrong way by them. However, that does not mean you should criticize or not have compassion for them.

Once you’ve taken refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, you don’t want to be best friends, dear close friends with people who put down your Dharma practice and your refuge objects. In the same way, if something is very precious to you, you’re not going to want to be best buddies with somebody who just disregards that and puts that down and ridicules you, and says, “Why are you doing that?”

Having taken refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and really trying to avoid harming others, not being rough and arrogant, and trying to be kind and accepting, then we don’t want to hang out with people who are drinking and drugging, and just spend hours hanging around, gossiping, criticizing other people and bad mouthing other people. If we hang around people like that, then we’re going to become like them and that’s the opposite of what we want to become, isn’t it? Having said that, that doesn’t mean that we’re rude to those people; it doesn’t mean you see your old friends and you go, “Well, you’re not a Buddhist so I’m not going to talk to you.”

Sometimes, it might even be our family members who disrespect our refuge objects or who are acting in very rough and arrogant ways. There we just have to be very clean- clear in our refuge, be polite to our family, join in activities, but really keep a distance so that we don’t get sucked into that kind of behavior and that kind of way of acting. There can be a lot of pressure from family members. But who our family members are is total potluck, isn’t it? You’re going to have so many different kinds of values among family members, different kinds of personalities, even when having similar genes and the same parents. So we’re polite, we’re friendly, but we don’t get really tight in a close way with these people and trust them with things, and so on.

Respect the monks and nuns as they are people who are making earnest efforts to actualize the teachings. Respecting them helps your mind for you’ll appreciate their qualities and are open to learn from their example. By respecting even the robes of ordained beings you will be happy and inspired when seeing them.

That goes for anybody, whether you’re ordained or you’re lay, to respect Sangha members. It’s not that you ordain and now you’re part of the Sangha so you no longer respect the Sangha. This is very easy. I’ve seen this happen to many people. When they’re lay people, they’re very respectful to the Sangha. Then they ordain and they think, “Now I am one of these people and I just treat them like I’d treat anybody else.” That really damages our practice. Sangha members should also respect other Sangha members.

This helps our mind. When we respect Sangha members, it’s not that we’re respecting their personalities because people can have all different kinds of personalities. You’re not respecting them as a person or as a personality. What you’re respecting is the precepts that are in their mind—and those precepts came from the Buddha. That’s what you’re respecting. When we respect the precepts and we respect people who keep precepts well, that really opens our own mind to learn from their example; and that, of course, benefits us. I’ve seen some people try to compete with the Sangha and say, “Those people are elitists and they think that because they are ordained they should sit in the front. I’m just as good as them, why shouldn’t I have that privilege?” That kind of attitude of competition or jealousy with the Sangha creates problems in ones own practice because again, you’re not respecting that person, you’re respecting the precepts that came from the Buddha.

If you’re a Sangha member and people show you respect, do not take it personally. They are not respecting you, so do not get puffed up. Don’t go walking into things and think, “I’m a Sangha member. Where’s the front row? I’m just going to put myself there because I’m special.”

It’s so interesting sometimes with Westerners. You can see the people who are newly ordained. Whenever there is a big teaching by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, they go sit in the very first row because they think, “Now I’m ordained so I’ll go sit in the first row,”— even above the seniors who’ve been ordained for decades and decades. There’s a kind of arrogance that comes to people because they’re wearing the robes. That’s totally inappropriate. Like I said, they’re not respecting you as a person, they’re respecting the precepts. When people respect you, you should think, “I have an obligation and a responsibility to keep my precepts well. These people are trusting me, they’re respecting that part of me. I should not be arrogant or dismissive of other people.” It’s very important. I like how it says “ … respecting even the robes of ordained beings you will be happy and inspired when seeing them.”

One of my friends from Dharamsala, one lay man who lived in New York City about twenty years ago, went back to New York City. Of course, there weren’t many monks or nuns there—especially in those days. He told me that one time he was in a subway station, he was changing subways, and on another platform he saw a monk. He was so overjoyed to see a monk that he just went tearing for that other platform, up the stairs, down the escalator and around to try to get there because he felt so happy seeing a Sangha member. I thought that shows a really good mind on his part—and it made him very happy.

Those are the guidelines specifically in relationship to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

Common guidelines of refuge

There’s also common guidelines of refuge. There are six of these.

1. Repeatedly take refuge

Mindful of the qualities, skills, and differences between the Three Jewels and other possible refuges, repeatedly take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha.

This relates to what we were talking about earlier. If you think of the refuges in other traditions, or if you think of the difference of how you relate to the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha when you take refuge, then that helps you to take refuge repeatedly.

2. Make offerings

Remembering their kindness, make offerings to them, especially offering them your food before you eat.

It’s important to think of the kindness of the Three Jewels, especially how all goodness and happiness comes from the Three Jewels. This is because it’s the Three Jewels that teach us what to practice and what to abandon. Therefore we know how to create good karma which is the cause of happiness. We make offerings to them.

Now, if you are a lay person in a family and if your family is Buddhist, then it’s really nice to stop and make the offerings together. I stayed with one family and the children would say the offering prayers. It was very sweet. The kids were very young and so we all held hands—the whole family—and then the children said the offering prayer. It was really very sweet. When we’re with Buddhist friends of course we can do that. If your going out to a restaurant, or you’re with non-Buddhist people, you don’t go, “Okay, everybody be quiet. I want to pray.” You don’t make a public demonstration out of this. You just let everybody talk and do their thing; and in your mind you do the visualization and make the offering. If it’s really hard for you to concentrate, go to the bathroom where you have a little privacy and then you can do the prayers.

3. Encourage others

Mindful of their compassion, encourage others to take refuge in the Three Jewels.

When we’re aware of the compassionate nature of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, then of course to try and get other people interested. We don’t push the Dharma on anybody. We don’t go on street corners and start passing things out. But we also aren’t shy. Some people go to the other extreme and they’re closet Buddhists—so that even at their workplace they don’t want to tell anybody when people ask what religion are you. They don’t want to say, “I’m Buddhist.” That’s going to an extreme. I think it can be very beneficial if you’re working at a place and they say, “What faith do you follow?” or whatever, you can say, “I’m Buddhist,” or “I’m studying Buddhism” or whatever you want. That can be really helpful to other people.

There was one person, … I haven’t seen her in many years. She worked for the FAA [Federal Aviation Administration]. She had bright red hair and she had lupus—so she was in a wheelchair. They used to call her ‘hell-fire on wheels’ because she had a very big temper. Miss ‘hell-fire on wheels’ started coming to Buddhist classes and she really started to change. One of her colleagues said, “What’s happened here? You’re really different.” And she said “I’m Buddhist and I’m practicing.” That was at the time when I was teaching the lamrim—the 150 series of tapes. This man took that whole series and listened to all of them. He became that interested. It can be really helpful to people. You don’t have to hide the fact that you’re Buddhist. People of other religions certainly don’t hide it.

One thing, if you’re in a situation where you’re with somebody who is trying to convert you to their religion, what I do is say very clearly and politely, “Thank you, I have my own faith. I think if you practice your faith and the kindness and the ethical conduct that are taught in your faith, it will be very helpful for you. I’m practicing the kindness and ethical conduct in my own faith. Thank you very much.” End of conversation. That’s if someone is really pushing and trying to convert you.

4. Take refuge three times in the morning and three times in the evening

Remembering the benefits of taking refuge, do so three times in the morning and three times in the evening by reciting and reflecting on any of the refuge prayers.

It could be the one, “I take refuge until I am awakened,”—the one that we always say. When we first get up in the morning, we should take refuge, and set our motivation. Before we go to bed at night, we should again take refuge and set our motivation. That acts as a very nice bookend for the day. If you have a tendency to forget to take refuge and set your motivation when you wake up, put a little sticker on your alarm clock, or put it on the mirror in the bathroom, or put it on the refrigerator, or put it on your steering wheel—so that you really pause and nourish yourself spiritually by taking refuge and generating your motivation.

5. Keep your refuge

Do all actions by entrusting yourself to the Three Jewels.

Whether you’re in a happy situation or a sad situation, whether you’re in danger, whether you’re in comfort—keep your refuge at all times.

6. Do not forsake your refuge

Don’t forsake your refuge at the cost of your life or even as a joke.

All of those guidelines are set forth to really help us maintain our refuge and to deepen it.

When I give the refuge ceremony to people, we always go over these guidelines. They are written out in the Pearl of Wisdom, Book 1. Also in Pearl of Wisdom, Book 1, there is a longer refuge and precept ceremony that I wrote based on Lama Yeshe’s teachings. It’s on pages 84-87 of the book. When people take refuge I ask that twice a month, either on new and full moon days or every other Sunday, whatever they want to do, twice a month, to stop and really go over the refuge guidelines. I encourage them to think about how well they’re keeping them. Go over their precepts that they took at the time of refuge, and then do some confession if they haven’t done the confession before. There’s a purification verse to say, which is the same one that the Sangha chants. Recite the longer refuge ceremony based on Lama Yeshe’s teachings. That’s on page 84-87. That includes also the precepts. I think that’s very good for lay people who have taken refuge, so that they really get reinvigorated. If there are a few of you together, then every other week you can meet together and do this. The guests at the Abbey, that’s what they do on the new and full moon days.

[Note: These have been attached to the end of this transcript for you.]

Questions and answers

Taking refuge from different teachers

Audience: Can you take refuge from different teachers?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Good question. Some people say that you can take refuge again and again with different teachers. Some people say that once you’ve taken refuge and the precepts you don’t need to retake them. You have it already. It’s very important when you take refuge, remember you’re taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. You’re not taking refuge in a particular Buddhist tradition or a particular Buddhist lineage. You’re taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha that are the same for all Buddhists. If you have taken refuge, and later on you’re studying with somebody else and you want to retake refuge to strengthen it, you can request that. If that teacher is a person who gives it again, then you can go ahead and do that.

Getting over the fear of breaking precepts

Audience: I’ve had a conversation recently with a friend of ours here who wants to take the precept of no intoxicants. He’s a sports fisherman, he throws the fish back and he thinks that he kind of wiggles out of that first precept about killing. But he’s so afraid that he’s going to break the precepts that he doesn’t want to take them. How do you encourage someone who really wants to but they still have this habit or fear that, “I’m not doing it perfectly, so I can’t.”

VTC: The question is how to encourage somebody who is hesitant taking precepts because they’re not sure they can keep them perfectly. If you could keep them perfectly, then you don’t need to take them. The precepts are trainings. This is why it’s important to translate them as trainings or precepts and not as vows. Vows gives you this idea of you have to do it ‘A #1 perfect’ or else. Whereas these are very much things that we’re training ourselves to do—they’re advice that we’re trying to practice because we know they are good for us. To take them you have to, of course, have some sense of self- confidence that you can keep them reasonably well. But you don’t need to think, “I’ve got to do everything number one perfectly or else.” Because who does things ‘A #1’ perfectly besides the Buddha? (Who doesn’t need to take the precepts.) But we need to take them. We take them because we can’t do them perfectly.

Taking refuge on your own

Audience: When they talk about taking refuge that opens the door in a way. What if a person really chooses to do it on their own? Do you really have to take refuge with another person?

VTC: Do you really have to take refuge through a ceremony with another person? I don’t think that it’s absolutely imperative. If you have refuge in your heart and there’s nobody around … You may live in a place where there are no other practitioners or whatever, you’re taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha and you have a direct line to them. At a later time maybe you want to take refuge—when you meet other people who are Buddhists you can do a ceremony. But refuge is a quality in your heart.

Audience: This is true for many people, like inmates and some of the people in SAFE (Sravasti Abbey Friends Education), who are way far away.

VTC: The inmates and some people who are doing the SAFE program, they live very far away. There’s nobody there to take refuge with. That’s why sometimes we do refuge over the phone. I’ve given refuge and precepts over the phone several times with inmates. I suppose it could be done for SAFE participants too—who live very far away and can’t come here.

Stepping over Dharma materials

Audience: I was thinking of people who step over Dharma materials. It’s not normally put on the floor. But some stuff is on the computer and I might use that on the floor. Should I treat that as Dharma material?

VTC: I always wonder about that too. Because if there is Dharma in the computer. You don’t see that. You see the computer. I think you should still treat it with respect, but … [end of teaching]

Appendix: Additional materials from Pearl of Wisdom, Book One, page 84-87: Refuge and Precepts

This ceremony is a good way for lay practitioners to purify and restore their precepts. It is good to do on full and new moon days, or twice monthly on any days that you can.

Purification Verse

Every harmful action I have done

With my body, speech, and mind

Overwhelmed by attachment, anger, and confusion,

All these I openly lay bare before you. (3x)

Renewing Refuge and Precepts

Spiritual mentors, Buddhas and bodhisattvas who abide throughout infinite space, please pay attention to me. From beginningless time until the present, in my attempt to find happiness, I have been taking refuge; but the things I have relied upon have not been able to bring the lasting state of peace and joy that I seek. Until now, I have taken refuge in material possessions, money, status, reputation, approval, praise, food, sex, music and a myriad of other things. Although these things have given me some temporal pleasure, they lack the ability to bring me lasting happiness because they themselves are transient and do not last long. My attachment to these things has in fact made me more dissatisfied, anxious, confused, frustrated and fearful.

Seeing the faults of expecting more from these things than they can give me, I now turn for refuge to a reliable source that will never disappoint me: the Buddhas, the Dharma and the Sangha. I take refuge in the Buddhas as the ones who have done what in the depth of my heart I aspire to do – purified their minds of all defilements and brought to fulfillment all their positive qualities. I take refuge in the Dharma, the cessation of all undesirable experiences and their causes and the path leading to that state of peace. I take refuge in the Sangha, those who have directly realized reality and who want to help me do the same.

I take refuge not only in the “outer” Three Jewels—those beings who are Buddhas or Sangha and the Dharma in their mindstreams—but I also take refuge in the “inner” Three Jewels—the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha that I will become in the future. Because I have the Buddha potential within me at this very moment and will always have this potential as an inseparable part of my mind, the outer Three Jewels will act as the cause for me to be transformed into the resultant inner Three Jewels.

The Three Jewels are my real friends that will always be there and will never let me down. Being free of all judgment and expectations, they only wish me well and continually look upon me and all beings with the eyes of kindness, acceptance and understanding. By turning to them for refuge, may I fulfill all wishes of myself and all beings for good rebirths, liberation and full awakening.

Just as a sick person relies on a wise doctor to prescribe medicine and on nurses to help them, I as a person suffering from the constantly recurring ills of cyclic existence, now turn to the Buddha, a skillful doctor who prescribes the medicine of the Dharma—ethical conduct, concentration, wisdom, altruism, and the path of Tantra. The Sangha act as nurses who encourage me and show me how to take the medicine. However, being surrounded by the best doctor, medicine and nurses will not cure the illness; the patient must actually follow the doctor’s advice and take the medicine. Similarly, I need to follow the Buddha’s guidelines and put the teachings into practice as best as I can. The Buddha’s first advice, the first medicine to take to soothe my ills, is to train myself in the five precepts.

Therefore, with a joyful heart that seeks happiness for myself and others, today I will commit myself to follow some or all of those precepts.

- From my own experience and examination, I know that harming others, specifically taking their lives, harms myself and others. Therefore, I undertake to protect life and to avoid killing. By my doing this, all beings will feel safe around me and peace in the world will be enhanced.

- From my own experience and examination, I know that taking things that have not been given to me harms myself and others. Therefore, I undertake to respect and protect others’ property and to avoid stealing or taking what has not been freely given. By my doing this, all beings can be secure around me and harmony and generosity in society will increase.

- From my own experience and examination, I know that engaging in unwise sexual behavior harms myself and others. Therefore, I undertake to respect my own and others’ bodies, to use my sexuality wisely and kindly, and to avoid sexual expression which could harm others or myself physically or mentally. By my doing this, all beings will be able to relate to me honestly and with trust, and mutual respect among people will ensue.

- From my own experience and examination, I know that saying untrue things for the sake of personal gain harms myself and others. Therefore, I undertake to speak truthfully and to avoid lying or deceiving others. By my doing this, all beings can trust my words and friendship among people will increase.

- From my own experience and examination, I know that taking intoxicants harms myself and others. Therefore, I undertake to avoid taking intoxicating substances – alcohol, recreational drugs and tobacco – and to keep my body and environment clean. By my doing this, my mindfulness and introspective alertness will increase, my mind will be clearer, and my actions will be thoughtful and considerate.

Having previously wandered in confusion and used misdirected methods in an attempt to be happy, today I am delighted to choose to live in accord with these wise guidelines of the Buddha. Remembering that the Buddhas, bodhisattvas and arhats – those beings I admire so much – have also followed these guidelines, I too will enter the path to liberation and awakening just as they have done.

May all beings throughout infinite space reap the benefits of my living in accord with the precepts! May I become a fully awakened Buddha for the benefit of all!

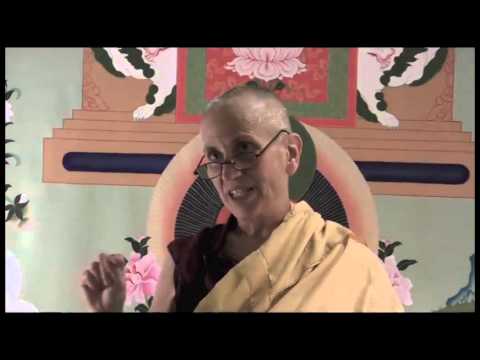

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.