Light: On Spiritual Women

An interview for Luce, a book and photo exhibition about spiritual women launched in Italy.

I was born in Chicago, but grew up in Southern California, where I graduated from UCLA and became a teacher. As a teenager and young adult, I asked myself, “What is the purpose of my life? What does it mean to be a good human being?” I examined several religions and philosophies and chose to follow the Buddha’s teachings because they made sense when I examined them using logic and reasoning, and they helped me be a calmer and kinder person when I practiced them. Also, I realized that I needed to improve my ethical conduct and could not continue to justify or rationalize my unkind actions.

I first encountered the Buddhadharma in 1975, when I was 24 years old. In 1977, I received novice ordination and in 1986, full ordination.

If someone had told me in 1975 that I would become a Buddhist nun, I would have said, “ Forget it, it’s not true,” but then the message was so true that it touched my heart, and I wanted to follow it. I still have many things to work on. I was married before becoming a nun, but didn’t have children. My husband and I separated because I wanted to become a Buddhist nun. My parents did not agree; I had done well in school, they wanted me to have a career and to have children. But after some years, my parents accepted my choice.

All Buddhist traditions have female practitioners. Some people say that only men can become Buddhas but according to Vajrayana Buddhism women can also attain full awakening. The hierarchical position for monks and nuns in religious institutions differs, mainly due to cultural reasons. At Sravasti Abbey, the monastery where I live in the US, gender equality is a strong value so monks and nuns are regarded equally.

All Buddhist traditions have teachings in common. The difference in traditions arose historically as Buddhism spread to new lands, where it had to adapt to different cultures and climates. Also, the various Buddhist traditions may emphasize the teachings in different sutras or stress a particular practice.

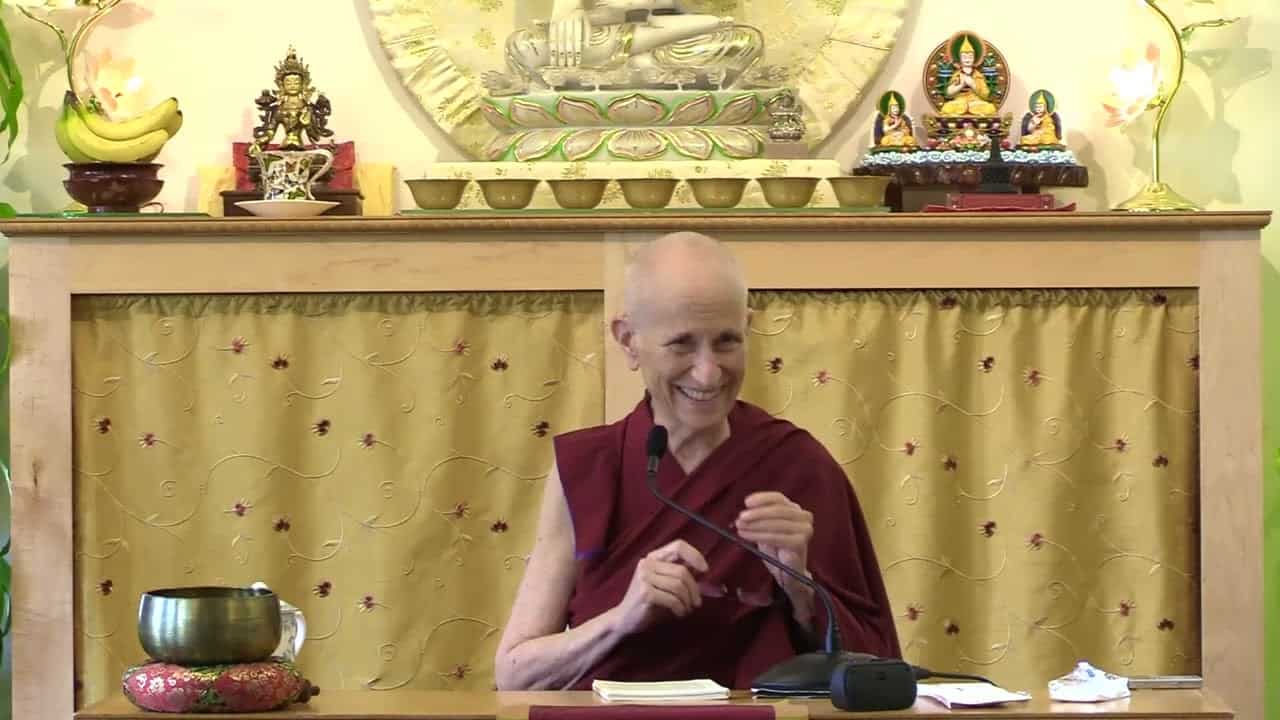

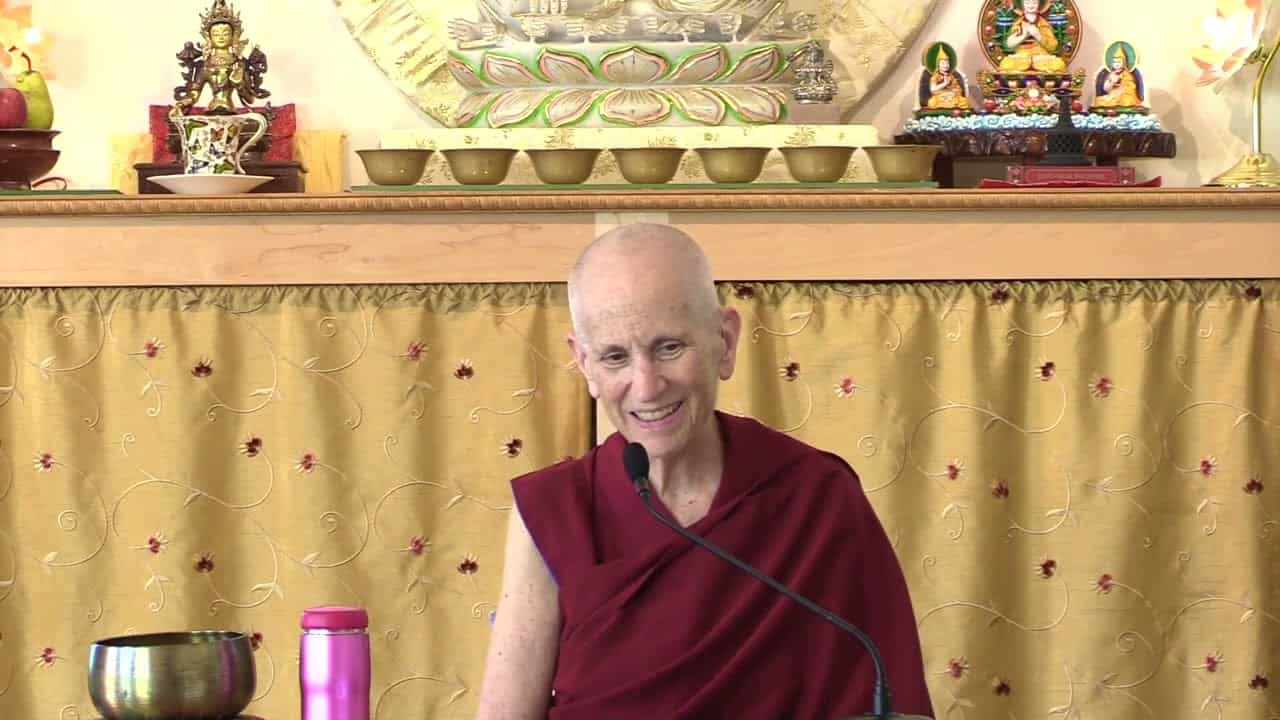

Lama means master or teacher. Venerable is an English word that refers to monks and nuns. Although I am sometimes in the position of being a Dharma teacher, I don’t like to call myself a lama because in my mind lamas are my teachers, who are much more advanced than I am. I do not have their qualifications and do not see myself as their equal.

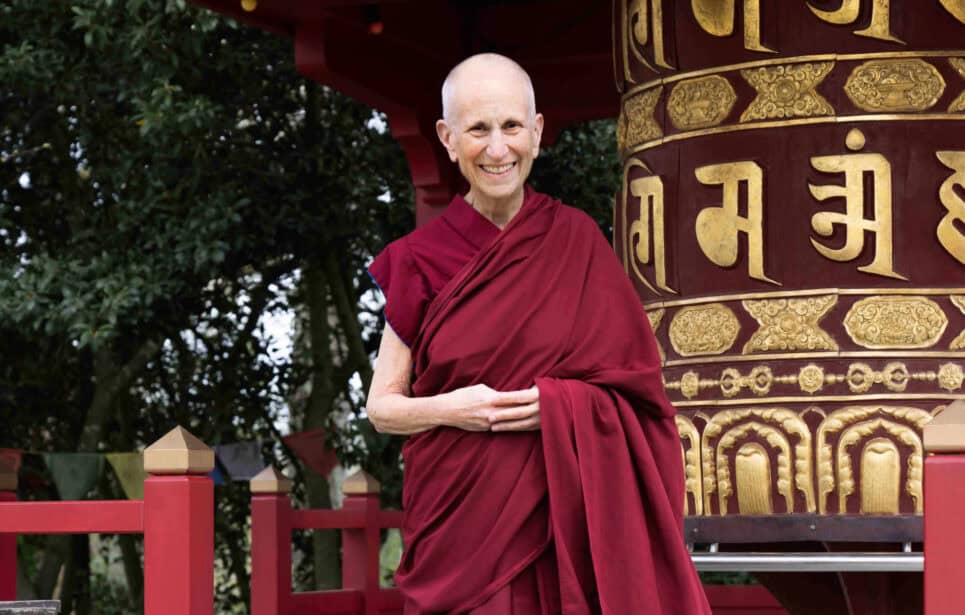

In 2003, I founded Sravasti Abbey, a Buddhist monastery in Newport, Washington, in the northwest US. We are a community of resident nuns and monks, both male and female. The Abbey operates on what we call “an economy of generosity.” In other words, we give everything freely. No one is charged for teachings or to visit us. We are completely supported by donations. When people appreciate the teachings and our work, they want to support it, so they give donations according to their means.

It is possible for a nun or a monk to live alone, but it is much better to live together in a community, where we support and encourage each other’s spiritual practice. Our monastery is, I believe, the only training monastery for Western monks in the United States. We have morning and evening meditation sessions and teachings. Everyone contributes to running the monastery. We call this “offering service,” not “work,” so that people are motivated to contribute their talents and skills to benefit the community and society in general.

My wish and hope for the world is expressed by Shantideva, a spiritual leader in eighth-century India. He said, “And may people think of benefiting each other.” Instead of saying, “I want, I want, I want, I want,” or “Go away, I don’t like it,” people think about how they can benefit each other.

Newport, Washington, US