Is anger beneficial?

03 Working with Anger

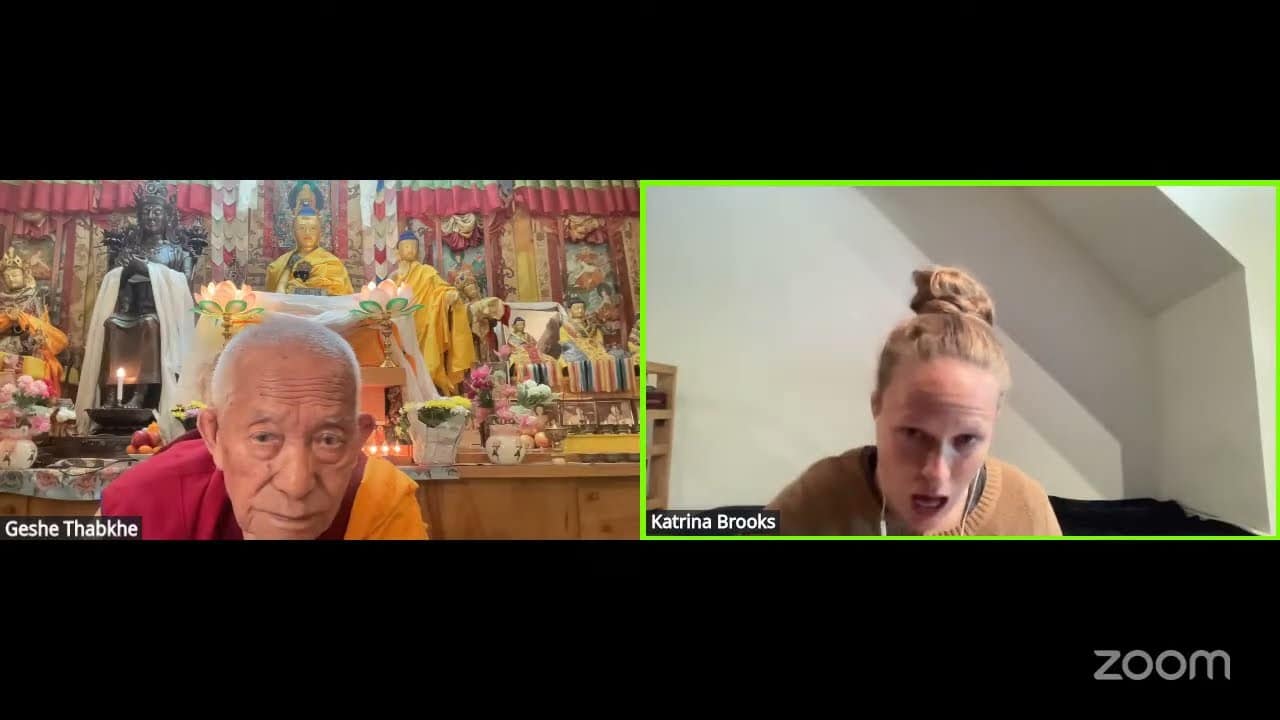

Part of a series of talks based on Working with Anger given at Sravasti Abbey’s monthly Sharing the Dharma Day starting in April, 2025. Written by Venerable Thubten Chodron the book presents a variety of Buddhist methods for subduing anger, not by changing what is happening, but by working with our minds to frame situations differently.

- Guided analytical meditation on the sense of self behind anger

- Examining our assumptions about our anger

- Perceiving situations through he distorted filter of “me, I, my and mine”

- We can influence others but we can’t change them

- Anger does not promote our happiness but makes us miserable

- We don’t communicate well when when we’re under the influence of anger

- If we could tame our anger we could avoid painful consequences

- The Buddha never said we shouldn’t get angry

- The story of a king, his angry son and a monk

- A story of road rage

- Questions and comments

An audio recording of the guided meditation is also available.

Anger includes many different emotions

Today we’re going to be talking about working with anger. I’m sure you all wish that some of your family members were here to listen to the topic, right? Because they really need to do something with their anger. But our anger is justified, isn’t it? Why? Because we’re right.

So, this makes situations very easy to solve. When I’m angry, I’m right and you’re wrong, so you change. It’s very simple. The problem is they say the same thing to us and then we disagree. Because, of course, we’re right and they’re wrong. And it just keeps going endlessly, doesn’t it? This happens on a national level, on a personal level, on a group level.

Our minds are full of anger. And when I say the word anger, I’m using it as a general catch-all word that includes things as mild as irritation and annoyance up through rage and extremism and spite and holding grudges and rebelliousness—the whole nine yards. We have lots of words in English for different kinds of anger, don’t we? We have lots of anger in ourselves.

And I think we have lots of anger as a country, don’t you think? Yeah. That seems to be the prevalent emotion now when people are so polarized. We tend to think that the problem is always external. It’s some objective situation out there, and we’re just responding in an appropriate way by getting angry. But those kind of assumptions, those ways of viewing our anger, they just perpetuate more and more anger. And they also make it so that we never question what’s going on inside. Because as long as the problem is out there and it’s what somebody else is doing or what somebody else is thinking or what somebody else is saying then there’s not much we can do except throw temper tantrums or beat them up or toss a few bombs or kill some people or starve some people. Look what’s going on in the world.

The root cause of anger

But if we really check up on our own experience, anger starts in here. That’s what the Buddha said, too. The cause of anger is the seed of anger that we have in here. And anger is rooted in our own ignorance. We don’t understand how we exist. We don’t understand how things exist. And so we have this idea of a big strong self whose happiness is very important, so we get attached to what makes us happy. And it’s always out there, too. And then whatever interferes with our happiness, something out there, then we’re angry and we want to attack it or get away from it.

This is kind of the story of our lives, isn’t it? And we have to really take some time and look inside and see how these assumptions lead us to misinterpret things and make the seed of anger ripen into a full grown plant. And then we have the repercussions of that.

So, it’s important for us to really look at the anger inside us, because that’s the only anger we can do anything about. And as long as it’s somebody else’s fault, then we make ourselves into victims. Working with Anger says:

Anger is also inaccurate in its assessment of reality, in that it does not perceive the situation in a balanced way, but views it through the distorted filter of me, I, my, and mine.

We think the problem is there, but what’s the filter we’re seeing it through? It’s some teeny, teeny periscope. You remember the periscopes they used to show in cartoons when you were little? You saw this little opening, and that little opening is me, I, my, and mine. We see every situation through that filter. There’s a whole world out there, but we look at it this one way: how it affects me. And we of course think that is the most important thing, the correct thing, and so on.

We’re not really seeing the whole situation. Although we think the way a situation appears to us is how it really exists out there—objectively—when we’re angry, we are, in fact, viewing it through the filter of our self-centeredness. Aren’t we? We’re viewing it through me, I, my, and mine. For example, if the manager criticizes my colleague, I may not get angry. In fact, I may even console my colleague by saying, “Don’t take what the boss said personally. It’s not a big thing. He’s under a lot of pressure, and it’s just venting. It doesn’t have anything to do with you, and he’ll be different tomorrow.” That’s what we would if the boss screamed at our friend.

But if the manager criticizes me, it’s a whole different ballgame. The manager can say those words to my colleague, and I will console them. It’s not a big deal. But if the manager says the same words to me then that’s now a national disaster. I’m upset. How dare somebody take me to task when I was doing my best, because I always do my best. Sometimes it takes me a while to do it, and I don’t do it in time. Sometimes I’m hurried, and I don’t do such a good job. But in the end, what I do is the best. Right?

So, if the manager criticizes me, I will likely be upset. The situation appears extremely serious to me. I dismiss anything my friends might say and dig myself more deeply into a hostile hole. But actually, no difference exists in the words the manager said to my colleague and the words that they said to me. Why then am I upset when the manager looks at me while speaking, but not when they look at my colleague and say those words?

It’s because it’s me. And as much as I don’t like to admit it, I feel that what happens to me is much more important than what happens to anybody else. Do you have some of those same feelings? You can admit it. We’re all alike. We’re with friends. You can admit these things. We don’t have to pretend to be the most magnanimous person in the world.

Anger and the self-centered mind

Due to this ingrained, self-centered view, anything that happens in relation to me seems incredibly important. Not just seems—it is incredibly important. I spend my time thinking about my problems, not anybody else’s, unless I’m attached to that person and it affects me. People could be starving in the world, my neighbor could be undergoing a horrible divorce and another colleague could be diagnosed with cancer, Russia could be bombing Ukraine and the Gazans may be starving, but none of that is really important. What is most important is what just happened to me. Right?

Some of you don’t think so. What do we get upset about? We get upset about what’s going on in Ukraine and in Gaza. But what do we get more upset about? After briefly acknowledging the misfortune of other people, I get down to the real crisis—the criticism that I just received. This may initially seem trite or like a flippant description, but if we observe what we spend our time thinking about, we’ll see that our problems and our life, everything related in one way or another to me, takes first place.

And we can see how the anger isn’t coming from outside because of the difference in response when words are said to somebody else and when they’re said to me. That shows that something’s happening inside me that’s generating the anger. It’s due to my interpretation of the event, my perspective on what happened, which is a quite limited perspective. And we love to place blame on other people because after all it is their fault. It’s always somebody else’s fault.

“I’m innocent. I do my best. It’s some jerk out there who is thinking crazy stuff.” Crazy means they don’t agree with me. That’s the definition of crazy, by the way. They don’t agree with me, and all these people should just change, and I’m going to make them change. Can we make anybody change? No. The only person we can possibly make change is this one. We can influence people in a positive direction. That we can do.

And we want to do that to help people. But can we make anybody change? We would sure like to, so we give them lots of advice because we can’t change them, but we can give them advice on how to change themselves. Right? And so we have advice for everybody, especially now in our country. Don’t you have advice for everybody? And they need our advice. And in case they have hearing difficulties or short-term memory loss, we will repeat it in loud voices and scream it in the streets. And maybe throw some things around to draw attention so that they realize that they have to change.

Dear Donnie wants to assign 2,000 California National Guard to the streets of Los Angeles. That’s going to really help people calm down, isn’t it? The people were demonstrating against ICE. And of course in this country we have the freedom to demonstrate peacefully. But then everything gets worked up.

And I remember this well from the Vietnam War days when I participated in protests. It’s so vivid to me. One time at UCLA there were protesters in one area and cops in the other. Cops were what we called them when we were polite. We had some other names for them. We never called them police. Cops was as good as we got. So, we’re protesting, and the police are lined up there with their riot gear. And the guy next to me picked up a brick or a stone and threw it. Before that, it had been peaceful. As soon as he threw that, I thought, “This is not going to help.” Because now our minds will become exactly like the minds of the people that we’re demonstrating against.

Who am I demonstrating against if my mind becomes exactly like their mind? Violence of any sort is not appropriate. But then when you’re talking about social issues many people say that we’ve got to be angry. Because if we aren’t angry, it just means we’re complacent, and we let it all happen. It’s as if there’s nothing else besides anger or complacency. There’s no other possible response.

I want to keep reading a little bit, but we’ll get back to that. The next section in the book is titled “Is Anger Beneficial?” What do you think? Let’s hear it for anger! When you go to football games and sports events, your anger comes out, doesn’t it? “hat team scored again, and it’s not my team. Why didn’t somebody block that?” All of a sudden where that ball goes is the most important thing in the universe. And you vent your anger. And then, if your team loses it gets even worse. How many brawls happen after sports competitions?

I went to USC for my first two years of college. And this was at the same time that O.J. played—what was his position? Linebacker? Running back. So, he runs backwards. I don’t understand football. [laughter] I just went to the game because I was dating some guy, and he wanted to go. So, there’s O.J., our star running back.And what is the USC side screaming to him? I heard it with my own ears. They were screaming, “Kill! Kill! Kill!” That’s what the crowd screamed to O.J., meaning score against the other team, demolish them. We’re the best. Well, O.J. got a few touchdowns, but he heard a lot of people scream kill. And that seemed to maybe plant a seed in his mind that wasn’t so useful.

Anger is not a cause of happiness

Is anger beneficial? We generally consider something beneficial if it promotes happiness. But are you happy when you’re angry? No, if you were happy, you wouldn’t be angry. You may feel powerful because the adrenaline is going, but are you happy? If we ask ourselves, “Am I happy when I’m angry?” the answer is undoubtedly no. We may feel a surge of physical energy due to physiological reasons, but emotionally we feel miserable.

Thus, from our own experience, we can see that anger does not promote human happiness. We can hold a grudge against somebody all we want. We can blame them all we want. Everybody in the universe can agree with us that it’s their fault. But does any of that make us happy when we’re angry? No.

In addition, we don’t communicate well when we’re angry. We may speak loudly as if the other person were hard of hearing, or we may repeat what we say as if they had a bad memory from one second to the next. But this is not communication.

That’s called screaming. That’s not called communicating.

Good communication involves expressing ourselves in a way that the other person understands.

It’s not just dumping our feelings on the other person. It’s not just venting. That’s not communication. Because we know what happens when somebody vents their anger on us and blames us for the situation. What do we do? If somebody’s screaming at you, telling you it’s all your fault, do you say, “Oh yes, I see, you’re perfectly reasonable. I’m sorry.” Do you say that? No.

What do we do? We instantaneously go into defensive mode. Even if somebody says something that is not a criticism, we will take it as a criticism and start explaining ourselves and defending ourselves and pulling out all of our ammunition so we can attack back. But good communication involves expressing ourselves in a way that the other person understands. It’s not simply dumping.

If we scream, others tune us out in the same way. We block out the meaning of words when somebody yells at us. I came from a family where one of my parents screamed because in my mom’s family, everybody screamed. It’s just a family habit. So, I grew up getting screamed at. And I learned something very valuable from that—don’t scream. It doesn’t do much good. Sometimes you need to talk loudly to really emphasize a point, but screaming, with its accompanying insults and exaggerations, doesn’t help.

Good communication also involves expressing our feelings and thoughts with words, gestures, and examples that make sense to the other person. Under the sway of anger, however, we neither express ourselves as calmly nor think as clearly as usual.

When we’re angry, we don’t think clearly. We may come up with what we consider a solution to the problem, but it only usually creates more problems. This situation in the Middle East is a good example. On October 7th, almost two years ago, Hamas attacked Israel. The world agrees a country can defend itself. So, they start defending themselves. They don’t look and ask, “What did we contribute to this? Why is this happening?” Instantly, it was “Those people are attacking us, trying to destroy us. And they’ve been doing it for a long time—ever since our country was established, they’ve been lobbing rockets and getting their friends to do that. So, we’re fed up, and the solution is to attack back and destroy them.” Where are we now with that? Fifty-five thousand estimated Palestinians dead; Israeli soldiers dead; Hostages: a few alive, many dead.

It’s not solving the problem, is it? Is Hamas helping to solve the problem? Hamas is using its own people as human shields and then blaming Israel for the destruction while they remain very comfortable under the ground. And everybody says, I’m right, and the other side’s wrong. And nobody wants to listen to anybody else’s grievance. One of my long-term friends that I know from India—she’s Israeli, but she married a Spanish man and lives in Spain—she goes to India every year, and she was telling me that at one retreat she was at, she started talking to another woman who was there. And they both really understood each other because they were both feeling so disturbed by the war in the Middle East, so brokenhearted about the killing and the blaming and the anger and the vengeance. They were really understanding each other and had a very good talk.

And then they realized that one of them was Israeli and the other one was Palestinian. And my friend wrote and she said that this is the kind of communication that needs to happen so that people can see everybody is hurting in very similar ways and to stop the blame game. I thought that was pretty amazing. There’s also a film that we’re going to watch here soon. What’s it called? “It doesn’t have to be this way” or “There’s a different way”—something like that. And it’s talking about some Israelis and Palestinians getting together and talking.

I visited Israel a few times in the late 90s and the early 2000s. At that time there was a group, and I hope it’s still going, called Seeds of Peace. And they would get Israeli kids and Palestinian kids, take them to the U.S., to a neutral place, and have these kids be at a summer camp and get to know each other and do arts and crafts together, play games together, become friends together. And they saw it as Seeds of Peace because the children, through personal relationships, begin to see—even if later things happen between the groups that they belong to—they can see that groups consist of individuals. And everybody in a group is not exactly the same.

When groups get mad at each other, we put a bunch of people together and think that they are all cookie cutters. And that’s all they are. Everybody thinks exactly the same way. But take yourself—do you think exactly the same way from day-to-day? Or do you change your mind? We change our mind. It’s very contradictory sometimes. Other people change, too.

And if you get a group of people together, boy, there’s going to be a lot of different opinions between them, even though there might be some things that they agree on. But when we make enemies out of a group, we make it a caricature. We act like everybody in that group is exactly like that. During the days of trying to make more racial equality in America, the big thing was to stop seeing people as stereotypes.

Racism is based on stereotyping. And everybody in that group is just a caricature—a stereotype that we make up in our mind. People who are racist, that’s what they’re doing. They’re not thinking clearly. But those people say the same things about the other people: “All those people who are in the superior group, they’re all alike. They’re all racist.”

It’s interesting because some decades ago the racists were the ones who were stereotyped. Now it’s people saying that we have to get rid of DEI, because those people are the racist ones now. But none of us are cookie-cutter human beings. It’s this whole thing of just blame the other side. This is really what’s going on now, that you can see: whatever you do, you blame the other side. This is the trick nowadays.

Under the sway of anger, however, we neither express ourselves as calmly nor think as clearly as usual. Under the influence of anger, we also say and do things that we later regret.

Oh boy, is that true or not true? Can you think of situations in your life where you were angry at somebody and said things or maybe even threw things or punched somebody? And then later looked and said, “Oh my God, what did I do?” And who do we say the most awful things to? It’s to the people we care about the most, isn’t it? We would never say to strangers what we say to the people in our families that we care about, but they’re just supposed to accept it because that’s the way we are and they love us. Do we accept them for all their blemishes, too? No, they should change.

Under the influence of anger, we also say and do things that we later regret. Years of trust built with great effort can be quickly damaged by a few moments of uncontrolled anger.

Isn’t that true?

In a bout of anger, we treat the people we love most in a way that we would never treat a stranger, saying horribly cruel things or even physically striking those dearest to us. This harms not only our loved ones, but also ourselves as we sit aghast as the family we cherish disintegrates. When you treat the people that you love that way, is it promoting harmony and goodwill and togetherness?

So, all of our relationships disintegrate.

This in turn brings guilt and self-hatred because we blame ourselves for what we said and that immobilizes ourselves and further harms our relationship and ourselves because we’re too sunk in feeling guilty and hating ourselves for saying and doing whatever we said or did. If we could tame our anger, such painful consequences could be avoided.

This is all under the section “Does anger create happiness?”

Further, anger can result in people shunning us. Here, thinking back to a situation in which we were angry can be helpful. When we step out of our shoes and look at ourselves from the other person’s viewpoint, our words and actions appear differently. Think of a time when you were really mad at someone.

It doesn’t matter why—maybe they were mad at you first and then you got mad at them. It doesn’t matter who started it. But step back and look at ourselves as the other person would look at us. And then we could understand why the other person was hurt by what we said. Because often we say things that really push people’s buttons when they’re angry. We do it quite deliberately.

While we need not feel guilty about such incidents, we do need to recognize the harmful effects of our uncontrolled hostility and for the sake of ourselves and others, apply antidotes to it.

Taking responsibility for our emotions

And there’s another thing to do. It starts with an A: apologize. Who me? When it’s their fault? Why should I apologize? They need to change. They need to apologize to me. We get really stuck in our pride and our arrogance, don’t we? I am not going to admit that I have any responsibility in this conflict. Because it really is somebody else’s fault completely, 100%. So, why should I apologize?

I once told a story about Lama Zopa telling people to apologize. And I’m not going to tell it here because when I told it there, people got so mad at me. I was just repeating what my spiritual mentor said, but it didn’t conform to people’s ideas. They got mad at me in the talk. I got angry email afterwards. It’s very interesting. But I’m not going to make that mistake again. You can just sit and dream about what it must be about. And if you’re really nice to me and promise not to get angry sometime in the future, I might tell you. But not now.

In addition, maintaining anger over a long time fosters resentment and bitterness within us. Sometimes we meet old people who have stockpiled their grudges over many years, carrying hatred and disappointment with them wherever they go.

Have you met older people like this? They are very bitter. It’s really sad. None of us wants to grow old like that. But by not counteracting our anger now, we allow it to build. And then we become like that.

Some people interpret Buddha’s teachings on the disadvantages of anger to mean that we’re not supposed to be angry or we’re bad and sinful if we get angry.

I’ve been accused of that too, many times. I’ll be giving a talk about anger and the disadvantages, and then people come up to me afterwards and say, “Well, you said we shouldn’t be angry, so blah, blah, blah, blah.” I always say, “No, please take out the tape and listen. I never said you shouldn’t be angry. I would never say you shouldn’t be angry. Because should doesn’t matter beans. That’s the best thing to say to somebody when they’re angry: don’t get angry; calm down. [laughter] It’s the same with “You shouldn’t be angry.” That really helps, right? [laughter] If we’re angry, that’s the reality of the state of our mind at that moment.

The question is not, should we be angry? The question is, do we want to continue to be angry? We’re already angry. Should doesn’t matter. But do we want to continue to be angry? In other words, am I staking out my territory? Am I defining my allies, defining my enemies?

And then I’m going to be angry and I’m going to be vindictive. And when I have the ability, I’m going to get even. This is what’s happening in the country.

The Buddha never said we shouldn’t get angry. And he never said we’re bad and sinful if we get angry. No judgment is involved. When we’re angry, the anger is just what it is at that moment. Telling ourselves we should not be angry doesn’t work, for anger is already present. Further, beating up on ourselves emotionally is not beneficial. The fact that we became angry doesn’t mean we’re bad people. It just means that a harmful emotion temporarily has overwhelmed us. We don’t need to go into good and bad.

We got overwhelmed by our anger. What are we going to do now?

Anger, cruel words, and violent actions are not our identity. It’s just what’s going on in our minds right now. They are clouds on the pure nature of our mind, and they can be removed or prevented. Although we are not yet well trained in fortitude, we can gradually develop this quality when we try to.

Ancient stories about anger

This is a new section called “Two Stories”:

We can notice in our lives the adverse effects of behavior motivated by anger. The Dhammapada, one Buddhist text, says, avoid speaking harshly to others. Harsh speech promotes retaliation.Those hurt by your words may hurt you back. An ancient story aptly illustrates this.

I love these ancient stories. Sometimes the setting is so culturally different than ours, but still the point is well made.

Once there was a king who ruled a great kingdom in India. He enjoyed a happy life, except that his young son would often quarrel with the ministers, servants, and other family members.

So, the king was happy, but his kid was a brat and didn’t get along with people.

Everyone found the son’s behavior unbearable, yet no one dared complain to the king.

This sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Hmm.

After some time, the king himself saw what was happening and sought help. He employed the best therapists, but they could not subdue the boy’s behavior, nor could the local sports heroes, miracle workers, and entertainers. In fact, the child’s behavior became more obnoxious.

How many of you were like this as a kid? A couple of you were like this obnoxious little boy, huh?

One day a monk came to town to collect alms. The king’s messenger observed him walking gently and mindfully and asked him to come to see the king. The monk, who had high spiritual realizations, declined this opportunity for riches and this opportunity to collect riches and glory by being invited by the king. And he said, I am no more bound to the worldly life, and therefore have nothing much to discuss with a king in the world. Hearing of the purity of the monk’s mind, the king went to pay homage to him and asked if he needed anything. The monk said that he simply wished to stay in the nearby forest, to which the king responded, that is my forest, so please live there. We will bring you food daily and will not disturb your meditation. I ask only that you allow me to bring my son to visit you. He is a big troublemaker and I’m at a loss as to what to do with him. The monk nodded in consent. The next day, the king and his son arrived at the royal forest in a chariot.

That’s the Rolls-Royce of ancient times.

The king returned to the palace while the monk and the boy walked in the forest. Suddenly, they came across a small neem tree and the monk asked the prince to pluck a leaf and taste it. The boy did so and spit out the bitter leaf in disgust. He bent over and forcibly grabbed the young tree by its trunk, pulled it out, smashed it.

“It’s the tree’s fault that I ate something that was bitter.”

The monk said to him, ‘My child, you knew that if this sapling were to continue, it would become a huge tree, which would be even more bitter in the future. For that reason, you plucked it out. In the same way, the ministers, royal officers, and palace residents now think this young prince is so bitter and angry. When he grows up, he will become even more vicious and cruel to us.”

Is this what you thought the monk would say? Or did you think the monk would just say, “You knew that the neem leaves were bitter. Why did you taste it?” Or something like that. But he didn’t. He made the analogy so that the little kid was that bitter leaf on a bitter tree that was going to grow up and become more bitter.

The monk continued, saying to the boy, “If you are not careful, they will pluck you from the kingship as soon as they can.” Understanding the disturbance he was inflicting on others and its ramifications for himself, the prince decided that he must change his attitude and behavior. Although it required effort, he knew it was for the happiness of all. And as he changed, others ceased their negative reactions to him and came to love and respect him.

It’s a “living happily ever after” story. But this young boy realized that his anger was going to bring adverse effects on him.

In a more modern episode, Floyd told me of his outbursts of road rage. Once while he was driving on the highway with his fiance, another driver cut him off.

Has this happened to any of you? Maybe your fiance wasn’t in the car, but somebody cut you off on the highway? I know you never do that to other people, but they might cut you off.

Infuriated, Floyd sped up, overtook the other car, and deliberately lurched in front of it, cutting him off. At such speed, he lost control of the car. It skidded across three lanes of highway and skimmed an embarkment before finally coming to a halt. Floyd suddenly realized that his rage had almost killed his fiance and deep remorse overcame him. He then stopped interpreting others’ poor driving as a personal affront.

Who knows how many lives have been saved by this change of attitude? If he hadn’t changed that attitude and always liked to retaliate against people who cut him off, somebody would have gotten killed at some point. So, he was able to change that or prevent that.

Q & A

Audience: You spoke a good deal about the more obvious forms of anger, like rage. I wonder about the really subtle ones. You used the term irritation. And it seems to me that anger can even transform into very subtle things like sadness.I was just wondering if you could talk about that end of the spectrum and how you might root out and discover the subtle ways that you get angry.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): Let’s first talk about sadness. Some people, maybe their angry might lead them to be sad, because there’s angry, angry, angry. And then they become sad about their anger. I don’t know. But sadness isn’t necessarily affiliated with anger. We can have compassion for people and feel sad seeing that they’re causing their own misery and inflicting misery on each other, but without being angry.

In terms of how to identify the subtler forms of anger, I think in some ways, it’s the same type of identifying that you use to identify the grosser forms, but it’s more subtle. Okay. So, you might check in with your body. Maybe your stomach isn’t as twisted, and your heart isn’t beating as fast, and the veins in your neck aren’t bulging as they do when you’re really enraged, but there’s some change in just how you feel inside. That might be an indication. Or sometimes you might just see kind of that your mood is going down a little bit. A bad mood doesn’t always correspond with anger, but sometimes anger can make a bad mood. And just also seeing our thoughts—if we’re starting to just go into either the blame game of how it’s somebody’s fault, or what we want to say to them.

When you’re mad, do you often ruminate and plan? Do you think about what you want to say to that person that is really going to let them know that what they did is unacceptable, and they must stop on orders of the king? Anybody else do that? You plan, you go round and around, you think of exactly the words to say, you know, that really can let somebody know that you’re unhappy. That can reveal to us that we’re angry.

Audience: I noticed sometimes my anger comes up when I don’t want to deal with a conflict or disagreement. And when it’s going to require some work from me. So, I’ll use anger as a tool to avoid.

VTC: So you use anger to avoid the conflict. But that doesn’t resolve it. We have two basic strategies. There’s the outbound and the inbound. The outbound is “It’s your fault, you’ll change,” and I’m going to yell and scream and throw things. The inbound is checking out: “I’m too mad to talk about this. I don’t want to deal with it, because I’m so mad and I’m afraid of my own anger.”

Some people are afraid of their anger because they can feel the intensity, and they’re afraid that they might hurt somebody or do something that they’ll later regret. So, what do they do? They check out. They leave the situation to go calm down. At that moment, if you think that you might become violent or say or do something, it can be wise to leave the situation. But before you leave the situation, don’t just check out and vanish because the other person’s standing there and you’re already gone, and the other person’s going, “What happened?” Just say to the other person, “I’m sorry, but I’m really angry now. I don’t want to say or do something that I regret or that hurts you. I need some time to calm down, and I’ll talk to you later about it.” Then at least the other person knows what’s going on

We don’t tend to do that. We tend to feel that we don’t want to deal with it. We can’t stand it. So, we leave, slam the door. First, we give the person a dirty look or burst out in tears. You can either burst out in tears immediately, or you can wait until you slam the door and go be alone. You have an option there. Sometimes you don’t burst out in tears, but you just get even more revved up. And so you go punch something, or you do what the experts a few decades recommended: you go out in the middle of a field and you scream. That really helps. [laughter]

Or you punch a punching bag, or you go jogging. Or you go take a walk in the forest, whatever helps you calm down. But it is helpful to say to somebody else, to acknowledge to yourself and to them, right now, “I can’t talk about this. I’m too angry. I will come back and discuss it.” In other words, I’m not just going off, calming myself down and saying, “Screw you.” Because the other person is upset. And that doesn’t help them if we just walk out. Communication is important.

But for some people—the inbound type—you slam the door, you say whatever you’re going to say, and you go sit in your room. You dig yourself a nice big hole of self pity. Because the world doesn’t understand you. And you have a big pity party: “I’m so angry. Why don’t these people understand me? I don’t mean any harm. Why are they talking like this to me? The whole world doesn’t understand me.” We have a nice pity party.

Pity parties are so wonderful, aren’t they? Nobody disagrees with you. Now everybody agrees with you that the world is to blame because they don’t understand and accept you. So, you can sit and have your pity party with its lead balloons. And this is too small of a thing of tissues. I need a big one when I have a pity party.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.