Women in Buddhism

A discussion while attending a conference in Bodh Gaya, India.

- The importance of being a nun is to receive teachings and ordination

- Gender equality is a Sravasti Abbey value

- The need to hear from more women teachers

- Tibetan nuns and bhikshuni vows

- Monastic teachers and lay teachers

Women in Buddhism (download)

Discrimination against women has always been a big problem. People who are always in the majority never see the problem because, “This is the way it’s always been.” They don’t see discrimination. Like in the United States with race relationships, white people don’t see discrimination, but the black people feel it. Because when you’re in the majority you just act the way everybody else does, and you’re unaware of this kind of discrimination. So, we’re dealing with that in the Tibetan Buddhist community.

When you go to China or to Taiwan, it’s different there. The nuns are very respectful to the monks, but they have full bhikshuni ordination, and there are about three times more nuns than monks. So, they are seen in society, and they are respected. They are teachers. They do a lot. And the monks appreciate them, and they praise them.

In the Tibetan community, women are headed for the back row—unless you are a lay woman who is a benefactor. Then you get a front seat. We’ve seen all this, yeah. What initially helped me with it was one day we were offering tsog at the main temple in Dharamsala and as usual, the monks stood up to offer the tsog and to distribute it. I thought, “Why can’t the women offer the tsog and distribute it?” And then I thought, “Oh, but if the women did that then we would all think, ‘Oh, look: the monks are all sitting there, and the women just have to get up and offer it and distribute it.’” So, I watched how my own mind reversed the thing and discriminated against women even though they now had the job that I wished they had. That was something to notice in my own mind.

Clarifying our purpose

I’ve been in this for many decades now, and I just had to clarify that I am here for the Dharma teachings. I’m not here as a member of a religious institution. So, the religious institution is male dominated, but if you have a good teacher and have equal access to the teachings then it doesn’t matter. You can receive the same teachings that the men do. I’m here for the teachings. I’m not here to take a position in a religious institution. I don’t care about that. It really hit me that the Tibetan religious institution is Tibetan. And we’re injis. They don’t see us as part of their religious institution. They’re happy to teach us; they’re happy to ordain us. And those are the two most important things: to receive the teachings and the ordinations—and the empowerments when we’re ready for them. That’s what I came here for, so I’m going to stay out of their religious institution unless they ask me to do something, and I’m going to do my own study and my own practice.

What I ended up doing was setting up a monastery in the US with nineteen nuns and five monks. The monks are very good. I’m their teacher; they accept a woman as a teacher. And we try to be as gender equal as we can. That’s one of our values. I always say it’s gender equal, but the guys can carry the heavy things. But one of our guys objected to that at one point and said, “There are some strong women here.” [laughter] Being in the West and doing our own thing, we aren’t part of a big religious organization. We’re an independent monastery. So, we set our own policies and ways of doing things. Several lamas have come, and I haven’t heard any criticism that there’s a female in charge and that most of the monastics are bhikshunis who have ordained in Taiwan. They come here and see a group of sincere practitioners, and they are happy with that.

As a child I always heard, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” So, when we go to India, we sit in the place designated for women or for Westerners. We don’t make a fuss. Years ago, some women really made a fuss and went to the lamas and complained: “You’re discriminating against us! You should stop this!” That was a big ordeal when they did that actually because the Tibetan monks said, “You’re angry. Anger is a defilement. We’re not listening to what you’re saying because you’re under the influence of a defilement.”

Seeking change in appropriate ways

Over the years I’ve become friends with some Tibetan monks, usually from the younger generation, and from time to time I’ll talk with them about it, but it’s just from time to time. At this particular conference, this one man stood up and asked the question, “Why aren’t there more women?” The monk who was the chairperson said, “I wasn’t in charge of organizing it. We’ll let the organizer handle it.” He completely dismissed it. He is a friend of mine, so I went to him afterwards, and he said, “We were short on time. There are many things to it, and if I’d gone on more, it would have been a longer answer.” I told him that he could have given a shorter answer, but the way it was handled, by shifting it, didn’t look good. Even if you had gone two or three minutes longer, you have to give some kind of answer.

In terms of the organizers, the chief organizer is Tibetan and his helpers are Chinese Singaporeans. Right after the conference, the right thing to do was to thank them for organizing it because it was a wonderful conference with so many people, and they had to find meals and places to stay for all of us. I think it went well. The presentations were good. But now that it’s been a couple of weeks, now would be a good time to write to the organizers and thank them for their work and say that it’s wonderful to see the Theravadas and Tibetans working together, but I would like to see more Chinese there. There were very few Chinese and also women. So, you could just say, “I think it would enrich the conference in the future to have more women teachers because most of the audience who come to listen to teachings are women, aside from the monks. So, it would be nice to have more female teachers.” They often say there aren’t that many female teachers, so you could also say, “If you need recommendations about good teachers, I could tell you about people I’ve studied with or learned from and maybe you could consider inviting them for the next conference. Women are half of the world’s population, so it only makes sense that they would be equally represented.”

You do it nice and politely. You offer to help. But it’s important that they get that kind of feedback. It’s also important that they hear it from men. They are naturally going to hear it from us women, but when that man stood up, I thought, “Yes, a man is asking.” It’s easier for them to listen to men. So, it can be helpful if you can have some of your male friends write the same thing very politely: “We really appreciate the Tibetan faith and Tibetan teachings, and we have a lot of faith in the Buddhadharma. We are not criticizing. We are trying to help the Dharma spread to more people.” You have to talk about what their goals are.

The other factor is the Tibetan nuns. They don’t have the full ordination. They are only novices, so they kind of run their own nunneries but not completely. There’s always a male abbot, or they are under the control of the Tibetan lay government. It’s a huge thing having Geshemas now. Some years ago there was a conference in south India on the celebration of Je Tsongkhapa’s 600th anniversary, and they invited many women to come and give presentations. One of the organizers was Thupten Jinpa. He’s a lay person now, but he lives in the West and is very attuned to this. There were many Tibetan women and some Western women at the conference.

We were talking with one Geshema recently, and she was saying that she had given a talk to the nuns. She had said in the talk that the leader in the monastery should be fully ordained and of the same gender as the monastics. Although she was not fully ordained, she was really hoping that the Geshemas could serve as abbesses and run the monasteries. They aren’t fully ordained, but they do have the Geshe degree. Actually, what she found was that the younger nuns said that they wanted a male abbot. The nuns have heard for years and years and years that bhikshuni ordination is not important. “You have the bodhisattva and tantric vows; you don’t need the bhikshuni vows.” Of course, they emphasize that it’s important for the men to take the bhikshu vows, so it kind of avoids that issue, but that’s where their mind is now. They’ve been told they don’t need those sets of vows, and they’ve been told it’s hard to keep them and that they will break them and accumulate much negative karma.

But in the monasteries we have the Vinaya, and we also have the rules of the monastery. And some of the rules, like not eating after noon, are not kept strictly. There’s a prayer you can say in the morning to account for that. So, if they took full ordination, they could do the same things as the monks do, and they wouldn’t be breaking things. The nuns have to want this from their side, though. And right now, most of them are more aimed at the Geshema degree. Because from the time I first came to Dharamsala in the seventies, the nuns hardly got any education at all. So, the Geshema degree that His Holiness really wanted is a really huge step. We need to rejoice in that. It will be better when they get to take full ordination, but the monks have not been able to figure out how to make that happen according to the Vinaya for whatever reason. Maybe they don’t really want it. That’s why as Westerners that we can go to Taiwan and do that.

But there are several western women who go to Taiwan and take the ordination, but they don’t want to stay for the whole program. They don’t want to go to the training program to learn how to be a bhikshuni. They just want to take the vows and say, “Now I’m a bhikshuni.” That is not presenting, as Lama Yeshe would say, a good visualization to the public. Because many of them live at home, so they aren’t part of a monastery. They have their own apartment. They have a car. They set their own schedule. They’re basically living as they were before. The older ones have pensions, but the younger ones put on lay clothes and go to work. It should not be like this.

The Vinaya very clearly states that if you ordain somebody, you are responsible for their livelihood and their teachings. But because the Tibetans are a refugee community, their priorities are setting up the monks’ monasteries. They are happy to ordain us, but we are supposed to support ourselves. As refugees, there’s some point to that, although the monasteries are much better off now. I came in the seventies, and the monasteries were dirt poor then.

I came personally to see it as a cultural thing. It’s important to be very clear about why you are here. I’m here for the teachings. It doesn’t matter who says them as long as that person knows the teachings well and is teaching me the correct view. That’s why I’m here. The politics belong to the institution, and they don’t consider me part of the institution. Here at this conference I was asked to give a presentation. I was totally shocked. “They asked me to do a presentation?” I was shocked, but of course I came. So, with the exception of when I talked to the moderator, I didn’t mention gender issues with any of my friends. Because I thought, “What they have to see is women who are competent. When they see women who are competent, then they’ll begin to think that maybe these women should have more opportunities and be given more respect.” In other words, when I was younger it was a problem for me mentally, but now I live in a monastery with wonderful people, men and women. We have good teachers, and I’m quite satisfied with that.

I want to help the Tibetan nuns, but I also see that they need to grow themselves. And I want to help the monks if I can, but the ones who are younger who are open and who you can discuss this thing with.

Questions & Answers

Interviewer: Thank you for that. You’ve brought a little bit more light into the topic. I had another question related to lay teachers and the sangha. I come from a yoga background. I’m a yoga teacher, and I was working with vipassana centers previously. I was supposed to guide the meditations for the retreat, but a sangha member asked to do it instead. I am young, but I have quite a bit of knowledge about how the body and mind work together. I also feel that I might have something to offer that a sangha member would not because they may not have the best qualities to lead. It seems sometimes that people are chosen because they are sangha members, not because they are qualified. So, I’m trying to figure out how to handle this in my own mind. Because I don’t want to have angry thoughts, and I don’t want to disrespect, but I’ve observed in the centers that people get these jobs because they are sangha, but they may not have the best qualifications to do that job. If you could give me a little advice on this.

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): That one is harder because the sangha are living in the precepts, and they have dedicated their lives to the Dharma. As a lay person, you may be teaching, but in the evening you can go to the disco or the pub or the movies. You can have a boyfriend or many boyfriends—or girlfriends or whatever it is. You’re free to do that. They aren’t. So, it’s out of respect for the ethical conduct that the sangha holds that the sangha has that position. It’s true that very often there may be a lay person who is more qualified, but since that person has chosen to live a lay life, not an ordained life, they give a different visualization as Lama Yeshe used to say.

For example, I talked to somebody who was following a different organization, and he said they would have teachings, and they would all go out to the pub afterward. I was really shocked, but the teacher was a lay lama, and the instructors were all lay people, so they did that. To me, that makes me wonder how well they understand the Dharma if they’re doing that. Like in the West right now, there’s a movement in which people want to take ayahuasca and get high. They say you get a rebirth experience and that it’s so in line with the Dharma, but why do you need an external substance to make you understand rebirth? Why not just think about the logic behind it and look at your own life experience and wonder why you are the way you are? I see this thing regarding lay and sangha more with Westerners. In Asia, the lay people respect the sangha, and they say, “I can’t be celibate. I want to have a family. I want to have a career. But I respect what you’re doing. Because you’re doing something that I can’t really do.” But when Westerners come to the Dharma, they haven’t been brought up with the idea of respecting people for their practice. It just looks like what you were saying with getting the job without having qualifications.

Interviewer: Thank you so much. I can’t thank you enough for the treasure you’re giving me right now. This is so needed.

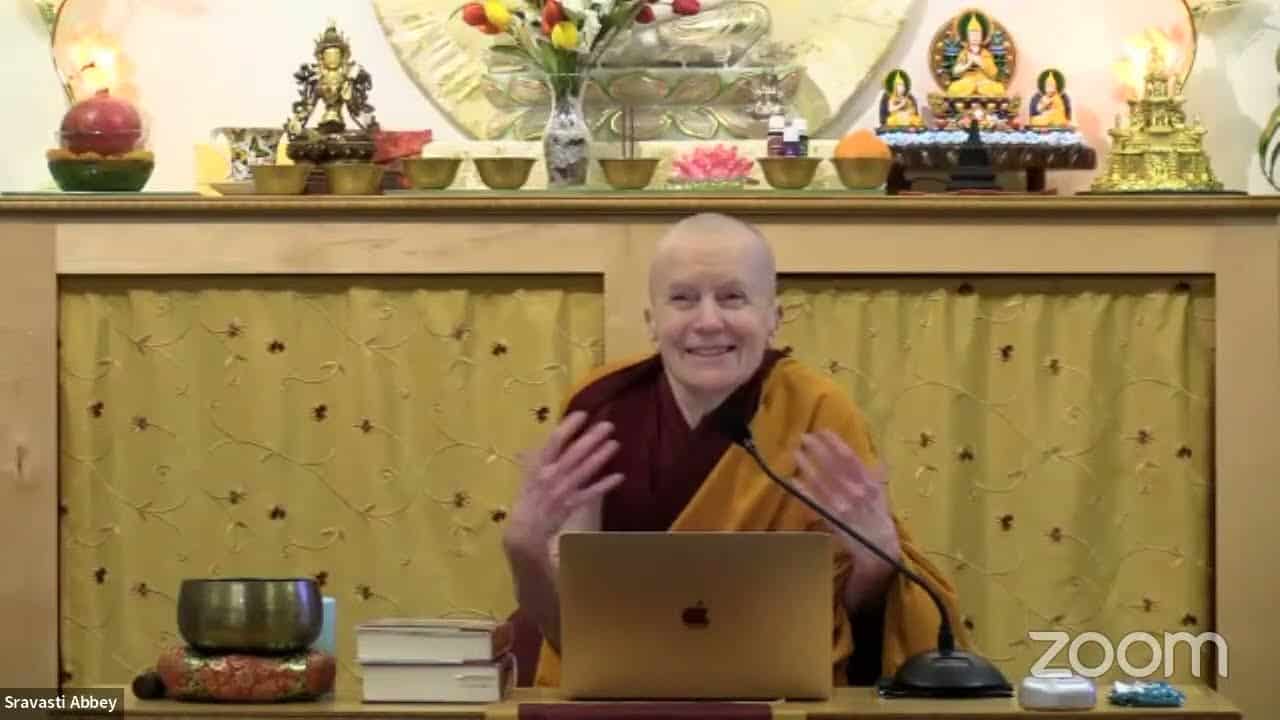

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.