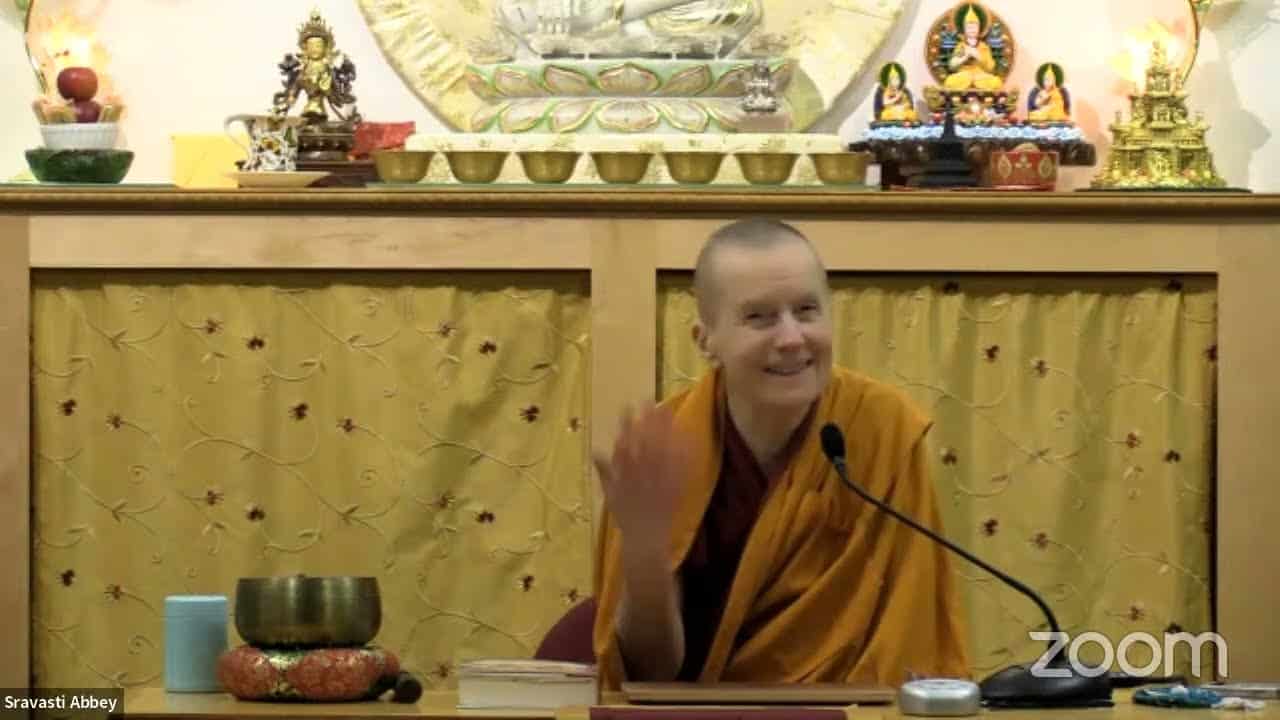

Sowing the seeds of Dharma in the Wild West

A talk given at Dharma Drum Mountain Spiritual Environmental Protection Learning Center in Taiwan. In English with Chinese translastion.

- How Venerable Chodron met the Buddhism and her teachers

- The decision to ordain

- Important experiences in Italy

- Teaching in Asia

- Introduction to Chinese Buddhism and ordination in Taiwan

- The challenges of living as a western monasitc

- Starting a monastery in western United States

- The generosity of Abbey supporters

- The growth of Sravasti Abbey

- Monastic life at the Abbey

- Questions and answers

- How do you work with those of different religons?

- Can we practice vipassina meditation and Tibetan meditation together?

- How did you know you wanted to ordain?

- What is the meaning of receiving and holding precepts?

- What are your thoughts on the development of Buddhism in the West?

- How can we work with anger?

I was asked to talk about my favorite subject—ME! So, I’m going to tell you all about ME! I was asked to tell you something about my life and about how the Abbey came about. I never anticipated when I was younger that I would be a Buddhist nun. I was born into a middle class family. My Grandparents were immigrants to America. I kind of just had an average childhood with kind parents. But I grew up during the Vietnam war, and I also grew up during the Civil Rights Movement in the US when there were a lot of demonstrations and sometimes even riots.

Ever since I was young, I questioned, “What is the meaning of my life?” The government was telling us we were killing people in Vietnam so we could all live in peace, and I said, “Huh? That doesn’t make any sense.” Our constitution said, “All men are created equal,” but they forgot half of the human population. Do you know who I’m talking about as the other half? [laughter] We were taught that, but in our own country not everybody was being treated equally, and that didn’t make any sense to me either.

So, I got interested in religion. I was raised Jewish, which is a minority religion. They believe in one God, but it’s not Christianity. But that didn’t work for me. The idea that there was a creator who created this mess of our world didn’t work for me. I thought, “In business, anybody who created this big of a mess would be fired.” I had all these questions, and I had a Christian boyfriend, so I went to the Priest and I talked to the Rabbis, but none of their answers made any sense to me in terms of purpose and meaning of my life.

When I went to University, I became kind of a nihilist. I studied History, and one of the basic things I learned was that in European history, in almost every generation, people were killing themselves in the name of God. I thought, “Who needs religion if all we do is kill each other for it?” That’s a rather cynical view, which isn’t particularly good, but that’s where I was at. I also grew up during the hippie era, so I had long hair down to my waist, and I had just pierced my ears. I won’t tell you what else I did because I might shock you, but you can just imagine. [laughter] I wasn’t born a nun. [laughter]

After school I went traveling around the world, and then I came back and went for a teaching degree. I was working towards that at a University and then teaching Elementary school in Los Angeles. On our trip we had gone to India and Nepal, and I really loved it there. In Kathmandu there were some Buddhist rice prints that we bought, and I thought, “Those are really cool. I’m going to put them on the wall of my flat and then everybody will think I’m cool because I’ve been to India.”

One summer vacation I saw a flier in a bookstore for a retreat taught by two Tibetan teachers. Since I wasn’t working in the summer, I said, “Let’s go!” So, there I went with my long, very brightly colored skirt, my embroidered peasant blouse, my long hair and my earrings, and I walked into the meditation hall. And I saw a man wearing a skirt and a woman with a shaved head. [laughter] They said, “The lamas are a little bit late. Let’s meditate until they come.” That was great, but I knew nothing about meditation. I had seen a picture of somebody in a magazine meditating, and it looked like their eyes were rolled back in their head. I didn’t want to look like I didn’t know what I was doing, so I copied that picture and sat with my eyes rolled back in my head. [laughter]

Thank goodness the lamas came quickly because it was giving me a headache! [laughter] When the lamas first started speaking, one of the first things they said was, “You don’t have to believe anything we say.” I thought, “Oh, good.” [laughter] They said, “You’re intelligent people. You think about it. Apply reason and logic and think about it. If it makes sense, good. Meditate, try it out. If it works, good. If it doesn’t work or it doesn’t make sense to you, leave it aside.” And I thought, “Oh, good. Now I can listen.”

But then when they started teaching, what they said made a lot of sense to me when I started reflecting on it. I didn’t know anything about rebirth, but the way they explained it and the logical reasoning they showed for why rebirth existed made sense. When I tried the meditation, it also really helped. I stopped being so depressed. After the course, I went back and did some meditation and a retreat. And then I thought, “I’ve always had a feeling that I don’t want to die with regret. This is really interesting to me, and if I don’t follow it, I’ll regret it later.” The lamas were teaching antoher course at their monastery in Nepal, so I quit my job, packed my suitcase and went to Asia again.

Until now, I’ve left out a little detail: I was married. [laughter] So, my husband went to a course taught by the Lamas in another part of the country, and when I said I want to go back to Asia, he wasn’t happy, but he went along. We were living at the monastery, and I hung out with the nuns a lot. I knew rather quickly that I wanted to ordain, which was really strange because I knew very little about Buddhism before that. But there was this really strong feeling that “This is something important, and I want to dedicate my life to it.”

I requested ordination from my teachers, and they said, “Yes, but you have to wait.” I wanted to ordain right away. [laughter] But if your teacher tells you something, you follow your teacher’s instructions. My teacher told me to go back to the states, so my husband and I went back. He knew by that time that I wanted to ordain, but I had to tell my parents, and they completely freaked out. They wanted a daughter with a different kind of personality. They wanted somebody who would get a very good job, make a lot of money, give them grandchildren, and go on vacations with the family. But none of that was very interesting to me. When I told them I wanted to ordain, they said, “What are we going to tell our friends? That friend’s daughter is a doctor; that friend’s daughter is a professor. And we have to tell them our daughter is becoming a…nun? And she wants to live in a country where they don’t even have flush toilets?”

They really liked my husband, and they were saying, “What are you doing? Did you take too many drugs?” [laughter] But when I thought about it, if I stayed and tried to be the kind of daughter my parents wanted, it still wouldn’t make them happy. They would still be dissatisfied with one thing or another. Also, I would create so much negative karma living a lay life—because I knew myself and my habits—that next life I would for sure have an unfortunate rebirth. If I have an unfortunate rebirth, I can’t benefit my parents or myself. I can’t benefit anybody. So, even though they disagreed, I knew that what I was doing was good.

My husband didn’t want me to leave, but he was incredibly kind. He was so kind, and he knew that when I have an intention, I do it. So, he let me go very kindly. But it still had a happy ending because my mother introduced him to another woman, and they got married. [laughter] And they have three kids. Sometimes when I go back to Los Angeles, if the Dalai Lama is giving teachings near where they live, I will stay at their house. And I’m so glad she’s married to him and I’m not. [laughter] But he’s a very, very nice man.

So, I ordained in Dharamshala. Kyabje Rinpoche, who was the senior tutor of the Dalai Lama, was my ordination master. I spent the first years studying in India and Nepal, and then one day at the monastery in Nepal, I was drinking a cup of tea and another nun walked by and said, “Lama thinks it would be very good if you went to the Italian center,” and then she kept walking. I was like, “What?” My plan in my head was that I was going to stay in Asia, find a nice cave with central heating and meditate and become a buddha in this very lifetime. [laughter] But my teacher was sending me to Italy. [laughter] And I thought, “What am I going to do there, eat spaghetti?” [laughter]

Learning from anger

There was a new Dharma Center, and I was the Spiritual Program Director. And I was also the disciplinary. There were a few monks there. These monks were nice people, but per Italian culture, they were very macho. [laughter] They did not like the idea of a nun, especially an American one with her own mind, being their disciplinarian. I didn’t think I had a problem with anger. I was never a person who yelled and screamed or anything like that. I just kind of held it in and cried. [laughter] But being there with these macho men, I discovered I had a problem with anger. [laughter] They teased me; they made fun of me; they interfered. They were horrible to sweet, innocent me who would never say anything harmful to them—except once in a while. [laughter]

In the daytime I would go to my office and do my work in the Dharma Center, and I would get so angry. In the evening I would go back to my room, and read Shantideva’s Engaging in the Bodhisattva’s Deeds. Chapter six is about working with anger and generating fortitude. I studied that chapter every night. And then every day I went back into my office and got furious again. Then I came back and studied the chapter. [laughter] This was a big thing to me, discovering I had anger. I realized that this was also my teacher’s way of training me. If he had said, “You know, dear Chodron, you have a problem with anger,” I would have said, “No, I don’t.” So, what did he do to show me I had a problem with anger? He sent me to work with these guys, and then I saw for myself that I had a temper.

So then my teacher came to the Center, and I came to him and asked to please leave there. I actually asked him if I could leave on the telephone before he got there, but he just said, “We’ll discuss it when I get there, dear. I’ll be there in six months.” [laughter] Finally, he came and said I could leave. My brother was getting married, and my parents called after not hearing from them in the three years since I left. When the person in the office told me my parents were on the phone, my first thought was, “Who died?” But they told me my brother was getting married and that I could come but to “look normal.”

Moving toward ordination

My teacher said it was fine to go, but he said, “You should be a California girl.” [laughter] A California girl was the last thing I wanted to be. But your teacher tells you something, so you try to do what he asks. The women in the Dharma Center dressed me up in lay clothes, and I grew my hair out a few inches so my mother wouldn’t cry in the middle of the airport. And then I got on the plane and went back. My parents tolerated it. It was okay. But they surprised me because they lived about forty-five minutes or an hour away from Hsi Lai temple, and they said, “Why don’t we stop there?”

They were in the middle of having a bhikshu ordination at the temple, and two of my friends who were also in the Tibetan tradition were there observing. When we got there, my parents talked to my two friends. My friends were also Buddhist nuns, and while they were talking I went for a walk. Later, when we got back in the car, my parents said, “They were such nice people.” What they didn’t say was, “It’s only our daughter who’s weird.” [laughter] So, I went back to Asia and then later I was sent to France. And then I came back to Asia before being sent to help with a new Dharma Center in Hong Kong. While in Hong Kong, I had the aspiration to take bhikshuni ordination. They don’t have the lineage for bhikshuni ordination in the Tibetan tradition; we have to go to Vietnam or Taiwan or South Korea. When I was in Hong Kong, I knew I could go to Tawan easily. I had enough money for that plane ticket.

One of my friends knew Venerable Heng-ching Shih, so when I arrived at the Taipei airport, she picked me up and took me back to her flat. She taught me all about Chinese etiquette: when you take your shoes off before going in the bathroom or the kitchen, and all these important things we don’t do in the US. I don’t know anything about Chinese Buddhism. She dressed me in Chinese robes and then put me on a bus. When I got off the bus, somebody from the temple picked me up and took me to the temple. When we got there, the lady who picked me up said, “Do you have a Chinese Buddhist name?” I told her I didn’t, so she told me to sit down while she went to ask the Master for a name. I sat there, and there were lots of people walking by because the ordination program was going to start. Somebody came by and said, “Amituofo,” and other people came by and said, “Amituofo,” and I thought, “That’s nice.” When the lady came back she asked if somebody had told me my new name, and I said, “I think it’s Amituofo.” [laughter] She looked at me in shock, like, “You think you’re Amituofo?”

So, that was my introduction. This was 1986. I was there for a whole month, and I was only one of two Westerners there. It was me and another older lady, and they were very kind to us, seeing as how we didn’t know anything. They were very concerned because they thought that both of us were losing weight. One morning, the doors opened to the dining hall where there were about 500 hundred people, and they walked in with a tray of Kellogg’s corn flakes and milk. Everyone looked at them and then they looked at us, and I wanted to crawl under the table because they came and put the cornflakes and milk in front of us on the table. I was so embarrassed. [laughter] That was part of my introduction to Chinese Buddhism.

Difficulties as an early monastic

My teachers then sent me to Singapore to be the Dharma teacher in a new center. That was really nice. I had some karma with the Chinese. And the situation for Western monastics, especially for the nuns, was very difficult because our teachers were Tibetans, and they were refugees. After the communists invaded Tibet in the late forties, in 1959 there was an uprising against them, and the Dalai Lama and ten thousand refugees fled. Those were our teachers. They were very poor as refugees, and their primary focus was to reestablish their monasteries. So, they were very happy to teach the Westerners, but they couldn’t build us monasteries or feed us or clothe us. We had to pay for everything.

Some people came from families that gave them a lot of money, and it was fine for them living in India as a monastic. My family didn’t give me any money because they didn’t agree with what I was doing, so I was quite poor. It was a good experience that taught me to save everything without waste, but it was very difficult. And then of course in India at that time, the sanitation wasn’t so good. We all got sick. I got hepatitis. We also had visa problems. India wouldn’t let us stay, so we constantly had to go and then come back on another visa. There were many problems with trying to live a monastic life there.

But I was very happy living there near my teachers, being able to go and talk to my teachers and to receive a lot of teachings. My mind was very happy. I wasn’t so happy to go back to the West. But the Western Dharma Centers were new, so some of us were sent to work in them. The Centers provided room and board, but if we wanted to travel somewhere else to go to teachings, we had to pay for our transportation, and we had to pay a fee for the teachings. We were basically treated as lay people. Buddhism was very new in the West at that time. It was before the Dalai Lama won the Nobel Peace Prize. When we walked around in our robes in the West, we would walk past some people, and they would think we were Hindus, and they would go, “Hare Rama, Hare Krishna.” We had to say, “No, no, that’s not us. We’re Buddhist.”

I remember even in Singapore people were very surprised to see white people who were monastics. I remember walking along the street one time, and a man walked by and was staring so much that I thought he was going to crash the car or something. One time somebody asked me to go to a restaurant for sanghadana for lunch, and when we walked in she said, “Are you aware everybody is staring at you?” I said, “Yeah, I’m used to it.” So, it was hard living in the East, and it was difficult living in the West. People thought we were weird. And what happened is that many Western monastics had to go and get jobs when they went back home. That means you put on lay clothes and grow out your hair a bit to get a job, and then when you go home you put on your robes and go to a Dharma Center. I didn’t want to do that, and I remember one of my teachers saying, “If you practice well, you will not go hungry.” So, even though I didn’t have much money, I believed what the Buddha said, and even though I didn’t get a job, somehow I’m still alive.

The birth of Sravasti Abbey

The wish at that time was really growing in me that I would like to start a place for Western monastics where they could live without worrying about having to work or having food, shelter, clothing and so forth. I was living in Seattle as the resident teacher for a Dharma Center. But starting a monastery is a really big thing, and the Dharma Centers are all lay people. I talked to some of my other friends who were also nuns, but they were all busy with their own projects. I didn’t want to start something alone, but they were all busy. One day back in Dharamsala, I went to visit one lama and was telling him I wanted to do this but couldn’t find anybody to do it with. He said, “Well, you’ll just have to start the monastery yourself.” [laughter]

Again, I was homeless at this time in the West without a particular place to live, and then I got a letter from a friend who lives in Idaho. Idaho is one state in the US that is famous for potatoes, so when I got this invitation to teach at a Center in Idaho, I thought, “All they have is potatoes there. They have Buddhists, really?” But I didn’t have a settled place to live at that time, so I went, and one of the people at the Dharma center knew about my aspiration to start a monastery, and so we went all over southern and central Idaho looking for land. I knew quite specifically the qualities I wanted in the land, and we didn’t really find anything there. But then some friends living in northern Idaho said they would look and wrote asking me to come up there. Before I went there they sent me a realtor’s website, and I looked on it and there was one place that was for sale in Washington State. I love windows and sunshine, and the picture of the house had lots of windows, so I said, “Wow, let’s go there.” Then I looked at the price and again said, “Wow!” [laughter]

I didn’t have much money. I had been teaching a lot, so I saved the dana I received from teaching and a few people had donated. But I certainly didn’t have enough to buy land. But we went to look at the place with all the windows. It was beautiful. The land is forest and meadows. There was a valley, but this was partway up the valley, so you had an incredible view. If you’re meditating a lot, you want to be able to walk in nature and to look into long distances, and this place was just gorgeous. My friend and I walked up the hill and then decided to go back to the barn and look. The real estate agent had to go, so we walked to the barn alone. I didn’t know that the person selling the property and the person buying property were not supposed to talk to each other, according to the realtor. But when we went back to the barn, the owner was there, and we started talking. My friend and I told the owner the property was lovely, but my friend said we didn’t have enough money to buy it and that the bank wouldn’t make a loan to a religious organization because if they foreclosed on it, it would look bad. My friend also told the owner that we didn’t have enough to make the down payment. The owner said, “That’s okay. We’ll carry the mortgage for you.”

Trusting the Three Jewels

Then the other thing was the planning and zoning code to make sure we could build a monastery there. The land just had a house and a barn and a garage. My friend who I was staying with was collecting the planning and zoning codes from all the countries we were looking for land in, and this particular county didn’t have a planning and zoning code in her collection. I told her, but it turned out that they didn’t have a planning and zoning code at all. It’s a rural area, and without a P&Z code, you can build whatever you want. We purchased the land and the first three residents moved in: me and two cats. [laughter] In the early days, I remember sitting there in the evenings wondering how we were going to pay the mortgage. And the cats just looked at me. [laughter] I was young when I ordained. I had never owned a car or a house or anything, and now here there is this mortgage that I’m responsible for. So, I just took refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha and knew that somehow it would work out.

As it turned out, it was a thirty year mortgage, and we paid it off early. We saved about thirty thousand dollars in interest by doing that. It was astounding to me that that happened. The area where we bought the land has hardly any Buddhists. There are hardly any Buddhists in the states in general, and we were in a rural area. We had a lot of forest land, so people would say to me, “Aren’t you afraid of walking in the forest with the cougars and the bears?” But I would say, “No, I’m actually more afraid of walking in New York City.” [laughter] The land is located in Washington state, which is on the west coast. This is the same state where Seattle is located, but it’s on the other side of the state. I had been teaching at a Dharma center in Seattle, so some of those people came over and started helping. They started a group called “Friends of Sravasti Abbey.”

The name “Sravasti Abbey” came about because I had submitted to His Holiness the Dalai Lama various names that I thought would fit, and he chose that one. I had suggested that one because it’s a town in ancient India where the Buddha had spent 25 rainy season retreats, so a lot of sutras had been spoken there. Also, there were very substantial communities there of monks and nuns. I thought that one of the principals of the Abbey should be that we don’t buy our own food. We’re only going to eat food that is offered to us. People can bring food, and we’ll cook it, but we were not going to the grocery store to buy food. People said to me, “You’re going to starve.” [laughter] Because in America, who lives like that? Everyone goes and buys their own food. But I just said, “Let’s just try.”

Early on, a journalist in Spokane, the nearest city to us, wanted to come out and do an interview to discuss what this “new thing” was and how we fit into the county. So, I told them about it, and I said also that we don’t buy our own food. We just discussed things about Buddhism, and they printed a very nice article about us in the Sunday paper. A few days after that, somebody drove up in an SUV that we didn’t know, and their car was packed with food. She said, “I read the article in the paper, and I thought that I wanted to give these people food.” It was so touching to see a complete stranger drive up with a car packed with food. It was such a teaching on the kindness of sentient beings. This is why in ancient times the sangha went on pindapada and collected alms. That’s the tradition we were trying to go back to. It really makes you experience in your own life the kindness of others. It’s obvious that you are only alive because others choose to share what they have with you.

We’ve never starved. [laughter] And we have retreats where people come and stay with the monastic community, and they bring food, and we cook it together. And everybody eats. Gradually people started to hear about the Abbey, and some people who were already Buddhists came to visit. Some people who knew nothing about Buddhism would drive up the road and say, “Who are you guys?” The local town has about 1500 people. It’s a small town with one stop light. We just went in very slowly. We didn’t do some big thing. We paid all our bills on time. That’s a good way to have good relationships with people. And people slowly started coming and participating.

Growing the Abbey

As more people came, we had to build more spaces. The first thing we did was change the garage into a Meditation Hall. It was interesting because before we even got the property some people had gifted us a big Buddha statue, and other people had gifted some paintings of the sages, and other people had gifted us the Mahayana Sutras and the Indian commentaries. This was before we even had the property and somewhere to put them. It was kind of like the buddhas were saying, “Come on, get the property ready. We want to move in!”

The first building was the Meditation Hall then we built a cabin where I would live. It had no running water, but I was very happy living there. I lived there for 12 years. Then we were running out of space for the nuns to live, so we built a residence for the nuns. And then we were running out of space for the dining room and the kitchen, so we had to build a new building with a dining room and kitchen. And then they really insisted that they needed a cabin with running water where I could live. I felt that I didn’t need it and was happy where I was, but they insisted that we build the cabin. So now there’s a small cabin where I live. And then we wanted to get more teachers there, so we built another cabin for guest teachers. We’re still growing. We have 24 residents now and 4 cats. [laughter]

But it’s still too small. We outgrew the Meditation Hall, so we were having the teachings in the dining room. When we had a lot of people there for retreats, meditation was also in the dining room, and this was not working so well. So, we decided to build the Buddha Hall. That’s our latest project. And we’re continuing to build the community and really emphasize Buddhist education. We want to make it where the sangha has a good education and knows the Vinaya. We do all the major Vinaya rites, such as the fortnightly posadha where we confess and restore our precepts; the three month Varsa retreat with a ceremony at the end of that, the pravaran; and the Kathina offering of robes ceremony. We do all these rites there, and all of them are translated in English so that we understand what we’re saying.

For women we give the sramaneri and shiksamana ordination, so the novice ordination and the training ordination. We have enough bhikshunis to do so in the community, so we give them there. Our dream for when the Buddha Hall is finished is to give the bhikshu and bhikshuni ordinations at the Abbey—in English. [laughter] The community is very nice. People are really harmonious, and you are very welcome to visit. You can come when we have a retreat or a course, or you can just come whenever and join the community in living according to our monastic schedule. So, that’s a little bit about the wild West. It is wild. [laughter]

Questions & Answers

Audience: You mentioned very early in your talk being critical of the Western religions because they didn’t make sense to you. But I noticed you have interfaith activities, so how do you reconcile those opinions with working with those other people with those religions?

Venerable Thubten Chodron (VTC): It’s no problem. We don’t have to all think alike or agree in order to get along. We get along quite well. There are some Catholic nuns who live nearby, and they said before we moved in, they were praying more spiritual people would move in. They were quite happy when we got there, and we get along very well. We talk about similar things that we do in our religion. It’s very enriching. We don’t have to believe the same things in order to get along. One year we were doing a retreat on the Medicine Buddha, and one of the Catholic nuns took the text we have and changed it to make sense to her from a Christian view. So, she did her retreat on seeing Jesus as the Divine Physician. It went very well with Medicine Buddha.

Audience: I come from India, and I would like to thank you for spreading the teachings of the Buddha. The teachings have been helping us for more than two thousand years. My question is regarding the meditation. I have been practicing vipassana meditation for quite some time, and I also practice the vajrayana that you teach. Can we practice vipassana and also the meditations that are taught in the vajrayana tradition?

VTC: Yeah, there’s no problem. The Buddha taught many different techniques because people have different inclinations and interests. To practice vajrayana you need quite a bit of practice of other topics before that, so it’s important to study and practice and seek out a really good teacher for that. But Tibetan Buddhism itself has a kind of vipassana meditation. It’s different from what you usually hear of as vipassana, but vipassana is taught differently depending on the tradition it is taught in. Like Chinese Buddhism, we have Medicine Buddha, Amituofo [laughter], Kuan Yin, Manjushri, Samantabhadra. All those are common in the different traditions.

Audience: How did you know right away that you wanted to get ordained, and did that happen before or after you found your teacher? Did it happen before or after you knew what lineage you wanted to follow also?

VTC: When I started, I knew like minus nothing. I didn’t know anything about what teacher or lineage to follow. But I did know that what these Lamas said was true for me, and I wanted to learn more. So, I just kept going back. They happened to be Tibetan Buddhist, and the way Tibetan Buddhism is presented with the emphasis on reasoning and logic fit very well with me. The lamrim or the gradual stages of the path, that approach to the Dharma, also fit very well with me as did the analytic meditations. So, I just kept going back and then I heard that you’re supposed to have a teacher. But for me, it happened very organically. It’s not like that for everybody. Some people just want to try out everything like it’s a buffet dinner, and some people go from teacher to teacher and practice to practice until they find something that suits them.

Audience: I am very deeply impressed by how you had the aspiration to receive the bhikshuni precepts and now have the aspiration to give the bhikshuni ordination in English. Can you talk about the meaning of receiving and keeping precepts to you?

VTC: Oh, wow. [laughter] First of all, the precepts give structure to your life, and it makes you be very clear about your ethical standards and your values. For me, I needed that kind of ethical structure, so the precepts were very helpful. Also, it involves changing your whole lifestyle. You live with other monastics, and you don’t collect a lot of things, and you don’t look at the stock market. [laughter] The whole way you live changes. When I was first ordained as a sramaneri, my focus was very much on my Dharma practice. I wanted to listen to teachings and to practice the Dharma. My teachers talked about bodhicitta, so yes, I wanted to benefit others, but everything was very much concerned with myself. But when I became a bhikshuni, my motivation totally changed because it really hit my heart that I have the opportunity to take these precious precepts because for 2500 years people have taken and kept the precepts and passed the ordination down from generation to generation. That’s why we have the lineage of precepts coming from the Buddha. It hit me so strongly that what I received by taking the bhikshuni ordination was like this big wave of the Buddhadharma coming from the time of the Buddha to the present, and I just got to sit on top of that wave, riding along, upheld by generations and millions of people who practiced. Even though I don’t know them, and they died centuries ago, it still became very strong to me that now I have the responsibility to maintain the tradition. I have the responsibility to do the best I can to keep my precepts and if I can to pass it on to other people. In other words, it’s not all about me anymore. [laughter]

Audience: My question is about the future of Buddhism in the West, especially because you mentioned that Buddhism is a religion based on reasoning and logic. It’s based on your reasoning that you have faith, not because a deity told you. When you think about Buddhism in the West, do you think the momentum is growing, or are there challenges we have yet to face?

VTC: I think it’s growing slowly but steadily. Just the fact that we have 24 monastics shows that. That’s a huge increase since we started. People are much more interested. There are a few challenges in bringing Buddhism to the West. There are a lot of lay teachers now, and the way they teach is sometimes very different from how the monastics teach. That’s one thing that can be a little challenging. The monastics are really following a tradition that we want to maintain whereas the lay teachers are a little bit more into adapting things from the West into what they are teaching. Some lay teachers have a lot of respect for monastics and some don’t, and that rubs off on their students, so some of the new Buddhists have respect for monastics and some don’t. Some will say, “You’re celibate, so you’re just denying your sexuality. What’s wrong with you?” That kind of attitude says to me that they don’t really understand what the Buddha is teaching. In those situations, many people are coming to the Dharma not seeking a path to liberation from samsara but seeking something that will help them to be calmer and happier in this life.

Audience: Thank you for sharing so many down-to-earth stories in this section. I would love to ask you a question about how to practice with anger.

VTC: Anger, oh. [laughter] Are you talking about your anger, or did you bring your husband with you? [laughter]

Audience: I am asking this because this is a pretty down-to-earth question in daily life and for all of us in this section and in the world.

VTC: The Buddha taught many, many ways to deal with anger. I could go on for another few years about it. [laughter] But I would recommend a couple of books to you. His Holiness the Dalai Lama wrote a book called Healing Anger, and I wrote a book called Working with anger. They are both based on chapter six of Shantideva’s Engaging in the Bodhisattva’s Deeds. Read those. It’s such a big subject, so I can’t really go into it now. You can find a lot of talks on ThubtenChodron.org about anger and lots of other subjects.

Audience: But what did you learn when you were in Italy with the macho monks?

VTC: The big thing I learned is that I have a problem with anger, and that anger destroys merit. I didn’t want to destroy merit. I also learned that all of the things in chapter six were really helpful. The biggest thing I learned was that when people do harmful things, what they are really trying to say is, “I want to be happy, but I’m suffering right now.” Whatever action they’re doing that is harmful to somebody else, because of their ignorance they think that action is going to bring them happiness. But it brings them suffering. So, that person should not be an object of my anger. They should be an object of my compassion because they are suffering. And they don’t know the cause of happiness and how to create that.

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.