The power of precepts

By D. E.

Restorative justice conceives of justice as repair to the harm caused by crime and conflict, rather than punishment. Understanding and responding to the needs of all parties involved and the broader community is central to the collective creation of a just outcome. D.E. participated in a restorative justice program that left a deep impact on him. Here is his reflection at the end of the program about how it relates to his Buddhist practice.

As a positive quality, a gift I claim and use with intent, I’ll speak of the Buddhist precepts. (I was studying them when I applied for this program.) The precepts are a gift that Buddhist practitioners receive from their teachers. They have been passed down from generation to generation. To truly receive them is to allow them to change your life. They are guidelines for how to lead a life that benefits all. They are not commandments, they can (and will) be broken. The test is to realize when they have been broken and atone for the break.

- Don’t kill, respect all life.

- Don’t take what is not freely given, but give freely.

- Don’t misuse sexuality, but respect all relationships.

- Don’t lie, instead practice right speech.

- Don’t intoxicate mind or body–keep them pure and clean.

- Don’t speak of other’s faults and don’t take credit for other’s work—don’t put self above others in any way.

- Don’t be possessive, give freely to those in need.

- Don’t harbor hate, practice kindness to all beings.

- And don’t disparage the Triple Treasure (the Buddha, teachings, and community); live a life which benefits all.

It is my intent to honor these precepts. To honor these precepts I will need to change many aspects of my former self. To sustain those changes, I vow to live by the paramitas—the perfections. They include generosity, ethical behavior (ethical behavior is akin to the behaviors described by the precepts), patience, enthusiastic effort, and meditations. When all of the paramitas are practiced, one’s practice is one of wisdom. If a precept is broken, I hope to find the wisdom to repair the break.

Buddhism does not look into the future. If I were to ask an acorn what kind of tree it would like to be in five years, and if it could answer, it could only give one answer. In that acorn, it has all it needs, its trunk, branches, and leaves, to become a mighty oak. It cannot become something else.

So, if you ask me who I intend to become in five years, I can only answer, “me.” But, to perhaps better answer the question, I’ll say a better, stronger version of who I am in this present moment. Coincidentally, in about five years’ time, I’ll go through an official Buddhist ceremony in which I receive the gift of the precepts. In that ceremony, I’ll also receive a Dharma name. That name will reflect who I’ve become. (Wouldn’t it be funny if I’m named “Mighty Oak”?) And to bring this response full circle, something I have learned about myself…

Before I found myself in prison, before I awoke to Buddhism, I thought that I was separate from the community I was in. I thought I could do as I please. I did not consider the effects my actions had on others. This class has shown me that my actions do indeed have a ripple effect. Buddhism teaches me that there is no separate, independent self, we’re all an “all.” This class has brought that lesson full circle.

More thoughts by D.E. on restorative justice:

These are the ten major bodhisattva precepts according to the Brahmajāla Sūtra. ↩

Incarcerated people

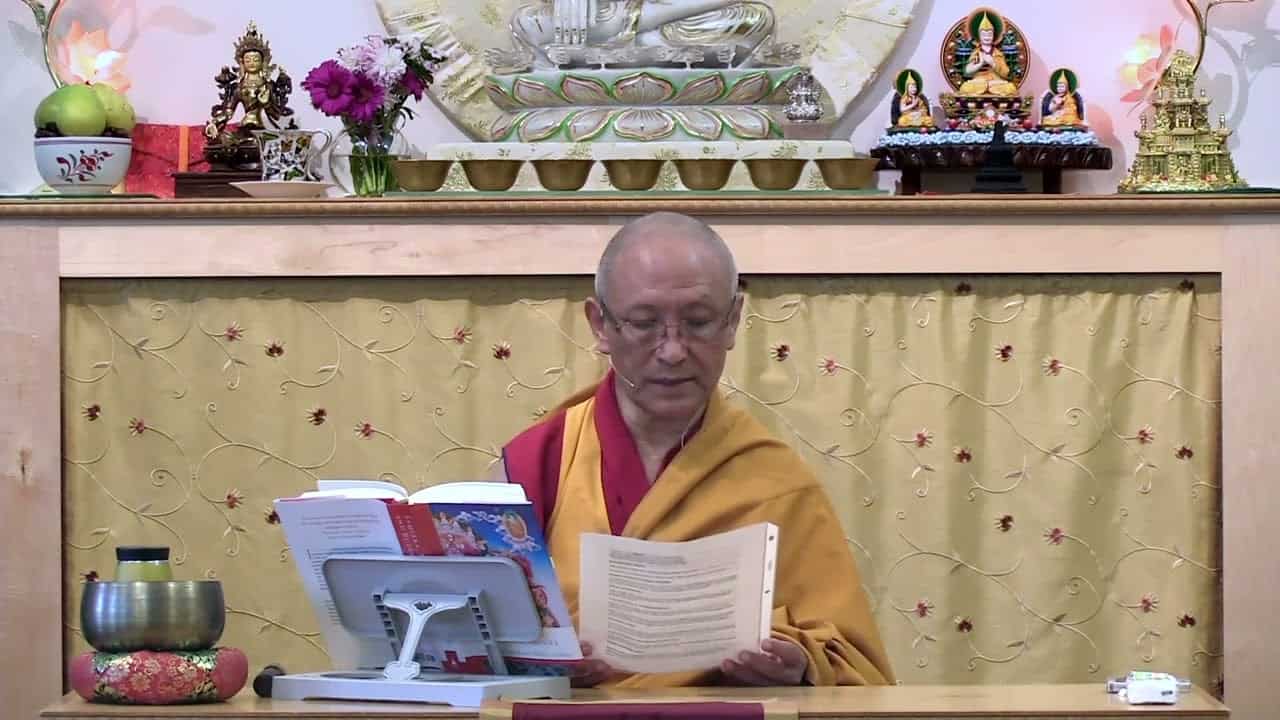

Many incarcerated people from all over the United States correspond with Venerable Thubten Chodron and monastics from Sravasti Abbey. They offer great insights into how they are applying the Dharma and striving to be of benefit to themselves and others in even the most difficult of situations.