Our top three priorities

06 Monastic Mind Motivation

Commentary on the Monastic Mind Motivation prayer recited at Sravasti Abbey each morning.

- Understanding impermanence eases suffering

- There is no inherently existent identity to cling to

- Bodhicitta prevents our motivation from being corrupted

We’ve been going through the lines of the Monastic Mind Prayer, and we’re now at the last line of it, having thoroughly actualized the previous lines. [laughter] This is kind of a summation of the previous ones:

In all these activities I will endeavor to remember impermanence and the emptiness of inherent existence and to act with bodhicitta.

That’s the basic thing that we should be paying attention to and doing. These are the realizations we want to gain. They are also the antidotes for so many wrong conceptions that we have. So, how do we use them and in what kind of situations? How do we keep these in mind? In all of our activities we need to remember impermanence.

Remembering impermanence

I remember reading something that Ayya Khema said once. She was giving a talk and she had a cup, and she said, “This cup is already broken.” And I thought, “That’s brilliant.” Because everything we have is in the process of changing moment-by-moment, never remaining the same. So, if we can look at it and think, “It’s already falling apart,” then we’re not surprised when it comes to the gross disintegration where we can actually see with our eyes that it fell apart. We’ve been aware the whole time that it’s not lasting.

Similarly, we can apply this to attachment for things we don’t have or attachment to keeping something we do have. We can remember: “This cup is already broken,” or “This relationship is already over; we have to separate sometime. We can’t stay together all the time,” or “This status I have is already gone.” We’re not going to have whatever status we have now forever. Whatever delightful possession we have is already broken, so use it but don’t get attached to it because it’s gone in the blink of an eye.

That way of thinking really helps us to accept the reality of things changing all the time. Because this is a big problem we have. When a change comes that we want, then it’s great! If it’s a change we didn’t want, then it’s awful. You see this a lot when people are friends or people are in a romantic relationship. One person is changing and doesn’t want to be as close or wants the relationship to change, and the other person doesn’t. So one person says, “Oh, the change is great! I get to leave and do this and that,” and the other person is going, “But, but, but, but!”

Imagine understanding from the very get-go: “Well, death is going to come up sometime or another, and that’s definitely going to separate us, and something may separate us before.” Do you ever think of the families in Ukraine? Two months ago they were still living as a family; they didn’t think there was going to be any separation. And then boom—like that, they are separated.

If we have that idea of impermanence then when changes come, whether we want them or don’t want them, we’re able to adjust and adapt. This really lessens our pain. You can see in our lives how much pain we’ve experienced when there’s a change that we don’t want, or especially a change that we didn’t expect. “I didn’t have this written in my calendar. If you had told me after such-and-such date you were moving to Timbuktu and I would never see you again, then it was okay. But you told me the night before you got on the plane, so I’m freaking out.” Whatever kind of change it is, if we have it in mind that it is going to change, then when it happens there’s not so much of a freak-out.

Remembering emptiness

Then the next part is about keeping emptiness in mind in all of our activities, or endeavoring to keep emptiness in mind. This one is really useful in our lives. Whatever position, job, career, or title we have, we often make an identity out of it and solidify that identity. “I am a this or that.” And then we add all these qualities that we think are inherent in that identity. “I’m this or that. Therefore, people should treat me like this, and they should always do that, and blah blah blah blah.” Of course people don’t, and we’re still grasping onto our identity, so we get very upset: “I am this, and you should listen to me.”

I’m going to use Venerable Semkye as an example. You are now usually pretty relaxed when I take you as an example. [laughter] It’s a big change she’s made; in previous years, I didn’t dare use her as an example. [laughter] Venerable Semkye and I have this thing every summer about what time of day you water the plants. Don’t we? Every summer we have this discussion. She turns on the sprinklers at dawn when the sun is coming up, and I say, “Don’t turn them on then, turn them on in the evening.” Because if you turn them on at sunrise the water evaporates, and it doesn’t get to the plants. If you turn it on in the evening it soaks into the ground, and it gets into the plants and nourishes them.

We’ve been through this for 18 years, I think, so there’s just a little bit of grasping at identities in this discussion we have. Because she’s the gardener and the landscaper. That was her career, and she knows that—she-knows-that! And I’m some pipsqueak who comes along and contradicts what she knows as the professional know-it-all about gardening. So, she’s hanging on to that. Meanwhile, I have the identity of: “I’m so smart, and I read somewhere that you water the plants in the evening, so that’s what makes me smart. I read it in a book.” I’m hanging onto my identity that I’m so smart because I know that. And the rest follows.

We have these discussions all the time at the Abbey, don’t we? Somebody says, “This is my department; this is my job, so I’m going to do it this way.” And there’s this grasping at “this is my possession; this is my job, and I know how to do it best!” While somebody else has a different idea, and they’re clinging onto “but I also have experience. I’m the person who has other experience, and I have a better way of doing it or another way or a different idea.”

We’re both clinging onto identities. We’re both becoming proud about what we know, either because we have the title or hold a certain position in the abbey. Or if you’re working at a job, you hold that position and therefore, “I know best.” And then the other person’s grasping onto “but I’m smart and I have different ideas and I’m sure they’re going to work just as well.” So, this is grasping at identities. And when we grasp at an identity, our minds become extremely inflexible because there’s this conceit of I. “I am this; therefore I know that. Therefore, you should relate to me this way as the person who knows that.”

And everybody is thinking that way. Whereas, if we remember emptiness, we realize: “Wait a minute, this position is only a label. It’s only designated to a set of chores that we do. It doesn’t make us better than anybody else.” But then we refute it: “But I am better than everybody else because I studied it. I have a degree—look at my piece of paper. I’m an expert!” So again, this is clinging, grasping: “That piece of paper proves that I am an expert. It means I am infallible and everybody should recognize I’m infallible about this department, because this is my position.”

And then of course the other person’s thinking something similar. They don’t have the title, so the person who has the title says, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.” And the other person who doesn’t have the title says, “But I have my own ideas, and I have whatever I’ve read and studied and what I feel. And you should respect me because I am I. I am me!” It’s very helpful to remember that all these are just conceptions of self that we are concretizing and holding onto as being an inherently existent me that is no longer dependent on causes and conditions, no longer dependent on being designated, but exists in “this way.”

For example, I am the person in the kitchen in charge of washing the dishes today. “Get out of the way! That’s my job. You see on the rota? It’s my name, so I’m going to do it my way. Don’t tell me what to do!” I think you get the idea. This comes up all the time, doesn’t it? Sometimes it’s about important things, and sometimes it’s about which way you put the stamp on the envelope. Because they’re “forever” stamps, and “forever” is written very tiny, and it’s hard to see which way the stamp goes sometimes. We can argue about that, and we both know exactly what’s right. Remembering emptiness kind of dissolves that, and we realize: “When I become the Buddha, then I’ll be an expert, and I won’t grasp it as inherently existent at that time. So, forget it and chill out right now, kiddo!” You say that to yourself. So, it’s very helpful to remember emptiness.

Remembering bodhicitta

The next important thing is to remember bodhicitta as the motivation for what we do. Then that pride that comes from not remembering impermanence and emptiness doesn’t distort our motivation. It doesn’t make our motivation one of attachment to reputation, attachment to what people think of me, attachment to who I am. Our motivation so easily gets corrupted by that. By understanding impermanence and emptiness, then our motivation of bodhicitta can really shine through a lot better because we don’t have that self interest. We’re not trying to protect ourselves in one way or another.

So, when we do the meditations on seeing the kindness of others, understanding their suffering, seeing the defects of self-centeredness and the benefits of cherishing others, then we can really come up with an altruistic intention that genuinely cares for others, minus the self-interest. That’s our work.

This afternoon at our meeting I’m supposed to talk about what our priorities are for the next year. It’s remembering those three: impermanence, emptiness, and bodhicitta. If you think of better priorities, tell me, but I am the expert in this, okay? [laughter]

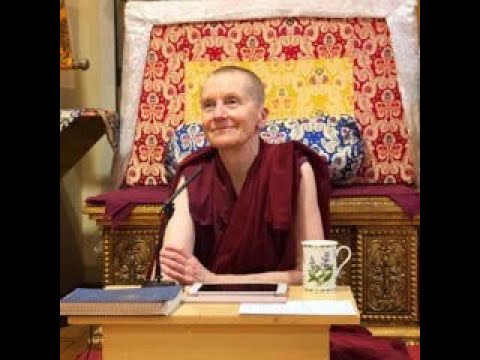

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.