Being mindful of our precepts and values

03 Monastic Mind Motivation

Commentary on the Monastic Mind Motivation prayer recited at Sravasti Abbey each morning.

- Our values are not things we’ve been conditioned by others to accept

- The goal of a worldly life is different from a life focused on the Dharma

- Reformatting how we think and changing our lives

I am still continuing the talk on the “Monastic Mind Motivation” that I started during our siksamana training program. During the program I got through one verse, and in the last BBC I got through the second verse. So, we’re on the third one now; we are moving along. Of course, each verse is one sentence. The next verse is:

I will be mindful of my precepts and values and will cultivate clear knowing of my thoughts and feelings, as well as how I speak and act.

“Mindful of my precepts and values” means that I will keep them in my mind, and then “clear knowing” can also be translated as “vigilance,” or my usual translation is “introspective awareness.” So, we keep the mind focused on the precepts and values: that’s the mindfulness part. The introspective awareness part is monitoring our body, speech and mind to see if we are acting according to our precepts and values. The way the word “mindful” is used here is very different from when they talk of being mindful in business and when you read about it in Time Magazine and stuff like that. Here, we’re talking about the Buddhist meaning of mindful.

So, why are we mindful of our precepts and values? It’s because our values are things that we have thought about hopefully, not just things we’ve been conditioned by others to accept. They are things that we’ve thought about and that we hold dear as directing us and giving meaning to our life. Among these values is keeping good ethical conduct. That’s where precepts come in because when you really want to keep good ethical conduct, then taking and keeping the precepts is how we do it. I always say taking the precepts is very easy. That’s not too hard, and it doesn’t take very long. Keeping them is a totally different ballgame. That’s when your practice really comes, because you have to keep them in your mind and then monitor what you’re thinking about to see if that corresponds to what you value and the standards you want to live by.

It’s the same with monitoring our speech, which is difficult sometimes, isn’t it? I don’t know about you, but with me, sometimes my words just come out and then afterwards I monitor them and think, “Uh-oh, that was a mistake to say that one.” But then it’s too late. It’s similar with physical actions. There’s sometimes a little bit more of an opportunity to pause between thinking and the physical action. But there, too, so many times we do something that contradicts our basic values and precepts.

Living life as a practitioner, we have to think about what our values are. Before we do that, it’s necessary to think about what our priorities are in life. And before we do that, it’s necessary to really think about what’s important to us and what our aims are. Many times people go through life without any clear aim or direction, just whatever comes along. What’s it called? “Going with the flow.” We did that for a long time. We just went with the flow. And the flow kind of went to some good places, but we also flowed to some rotten places. I’m sure we all have many stories about that. Once we become a Buddhist practitioner and start learning the Buddhist worldview, how we look at life really changes. What is important to us changes. What our aims are in our life changes.

Because so often in worldly life, what are our aims? There’s kind of a standard recipe. You graduate school on Friday and start work on Monday. You work for the next 45-50 years. Somewhere in there you get married, and then a few years after that you have your 2.2 children. A few years after that maybe you’ll still be married, but according to the divorce rates nowadays, chances are better that you won’t be. Then you keep working to support your family, and hopefully you rise up the ladder. You get more prestige. You get a raise, and you buy a nicer house. Then you watch your kids as they graduate, get married, and give you grandchildren. That’s kind of the standard formula. Somewhere in the middle of that, unbeknownst when, you get sick, and of course you’re aging the whole time. And at some point you die. That’s the end of the story.

When Dharma is the center of your life, that’s not the flow of your life. It isn’t your aim to accomplish those kinds of things. You don’t have a job. Even though you’re the servant of all sentient beings, you don’t have a job. You’ve left the home life for the homeless life. You don’t have a family supporting you. And your aims in life are to progress along the path to Buddhahood by hearing, thinking and meditating on the Dharma—by planting seeds in your mind. Hopefully, some of those seeds will ripen and deeper understanding will come. Then at some point somewhere, in some lifetime, you will have some realizations. But those realizations coming in this life? Hmmm. You know what they say when you generate bodhicitta: “Hope to attain enlightenment but don’t count on it.” So, you have realistic expectations of what you can accomplish.

Your priorities in life are accomplishing those things: hearing, thinking, and meditating on the Dharma; integrating it in your life; helping to spread and preserve the dharma that we’ve inherited; and helping other people along the path in whatever way we can. We all have very different talents and abilities to do that, so we see what fits us both the best. At the same time as we help others, we continue to deepen our own practice. It’s not like you get an education and then you stop Buddhist school, and now you go out and you do something. We are always students until we attain full awakening. Our own practice always has to be a priority.

Based on what we want to attain in our life, then we set our priorities. It takes a while to really generate the Buddhist worldview in our mindstream, get our priorities straight, and then make our life correspond to those priorities and to what we think is important. This involves a total revamping of what we’ve held as true in our beginningless samsara and what we’ve learned in this life since we were born. The more I get into it after all these years, the more I see it’s completely changing how I look at things. It’s a gradual process, and you have to keep doing it.

So, you live in society, but you don’t think like a lot of other people think. On certain things you can think the way they do. Like we know vitamins are good for us. Of course, I’m sure now there’s somebody who politicizes vitamins. [laughter] We agree with society about certain conventional knowledge. In terms of what is important and meaningful, what the purpose of our life is, we don’t fit in with regular people. But we live among them; we see them as kind; and we benefit them. Really practicing is reformatting how we think and then changing our lives—slowly, slowly, slowly. We change how we live in the world and how we speak to other people. And how we think begins to correspond with our priorities and our values.

That’s where this mindfulness comes in, because we have to be mindful of these things. We have to hold them clearly in our mind. If we don’t, we’re going to slide down the slippery slope and wind up where we were before. So, it’s important to be mindful of them and to have that monitoring mind. That’s what we call the introspective awareness that monitors: “What are we thinking and feeling? What are we saying? What are we doing?” And it tries as much as possible to keep our body, speech, and mind in line with our values, priorities, and aims in life.

That’s part of what we’re saying to ourselves every morning when we recite this—as you’re saying, “Okay, now I get to stretch my knees and breakfast is soon.” [laughter] But, it makes an imprint, and we need to keep thinking about it.

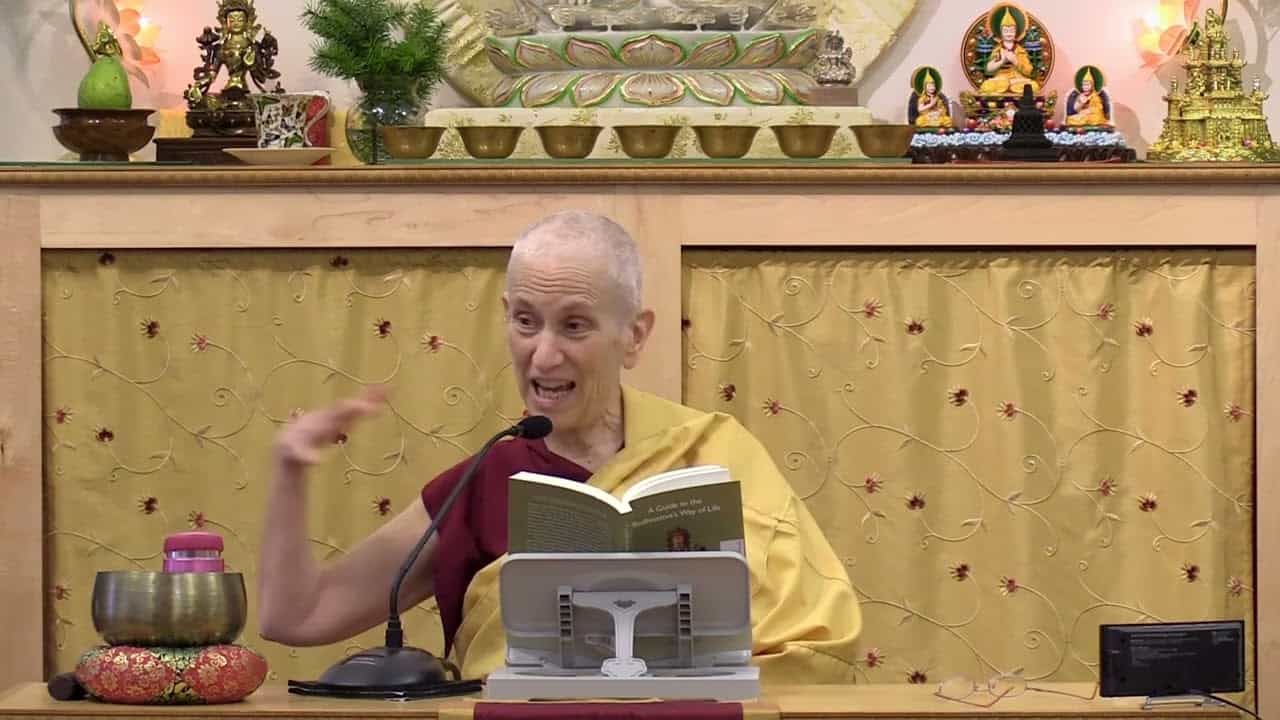

Venerable Thubten Chodron

Venerable Chodron emphasizes the practical application of Buddha’s teachings in our daily lives and is especially skilled at explaining them in ways easily understood and practiced by Westerners. She is well known for her warm, humorous, and lucid teachings. She was ordained as a Buddhist nun in 1977 by Kyabje Ling Rinpoche in Dharamsala, India, and in 1986 she received bhikshuni (full) ordination in Taiwan. Read her full bio.