Racism as a public health crisis

Ongoing police brutality against African Americans and the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus on racial minorities have spotlighted the effects of racism on health, and a number of cities and counties are now passing resolutions declaring racism to be a public health crisis.

U.S. Cities Declare Racism a Public Health Crisis

For example, about a week ago, the Boston mayor called racism a public health crisis and said he would reallocate $3 million from the city police department’s overtime budget to address the issue, and would consider transferring an additional $9 million from the police department to support initiatives for housing and women and minority-owned businesses.

The city councils of Cleveland, Denver, and Indianapolis have voted to acknowledge racism as a public health crisis, as well as officials in San Bernardino County, California and Montgomery County, Maryland.

In August of last year, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin became the first local government in the country to declare racism a public health crisis and pledged to assess all government policies for racial biases and mandated training for county employees on the effects of racism.

Some state legislators in Ohio have introduced a bill that would make it the first state to declare racism a public health crisis. In a recent interview, Ohio House Minority Leader Emilia Sykes said there are two viruses plaguing U.S. communities, one of which came into existence within the last year, and the other of which has been around for over 400 years.

What is Institutionalized or Systemic Racism?

As we learn in the Buddhist system of reasoning and debate, when we want to analyze an issue, we start by looking at definitions to make sure we’re all on the same page.

So what exactly is institutional or systemic racism?

According to the former president of the American Public Health Association, Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones, institutionalized racism is “a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks – which is what we call “race” – which unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities, and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.”

An article published on the National Institutes of Health website entitled “Uprooting Institutionalized Racism as Public Health Practice” says that “institutional racism” refers to ways both state and nonstate institutions discriminate, through policies and practices, on the basis of racialized group membership.

This article identified two main racist ideologies used to explain longstanding Black–White disparities in health. The first argument is the biological inferiority of non-Whites, which dominated U.S. medical thinking in the 18th and 19th centuries. The second argument, which is currently predominant, holds that African Americans choose to engage in behaviors detrimental to their health. The article criticizes this “lifestyle hypothesis” as faulty because it overlooks racially-based patterning of power and opportunity and ignores the toll of lifelong discrimination on health.

What is a Public Health Crisis?

So then, what is a public health crisis?

One online source defined it as an occurrence or imminent threat of an illness or health condition that has significant impacts on community health, morality, and the economy.

Racism as a Public Health Crisis

Though recent instances of police brutality and the coronavirus are spotlighting the effects of racism on health, some researchers and activists have been calling racism a public health crisis for decades, such the Portland-based advocacy group Right to Health, which in 2006 began urging the National Institutes for Health and Center for Disease Control to declare racism a national health crisis.

This is because the United States has a high degree of health inequity, which the American Public Health Association defines as the uneven distribution of social and economic resources that impact individuals’ health. Public health researchers agree that many of these inequities stem from structural racism and the historical disenfranchisement of racial and ethnic minorities.

Racial minorities have been systematically withheld from obtaining resources needed to be healthy and are disproportionately exposed to combinations of health risks such as poverty, poor housing, environmental hazards, and violence – both at the hands of police and private citizens.

Exposure to these conditions has resulted in higher rates of infant mortality, heart and lung disease, and diabetes among African Americans and other minority groups.

The psychological stress and trauma of dealing with racism is being recognized as a public health problem within itself. A professor of behavioral health at the University of Alabama cites systemic racism as a chronic stressor that negatively impacts the physical, emotional, and mental health of African Americans across their lifetime.

The American Psychological Association has found that stress associated with racism increases an individual’s risk for chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Researchers are now looking at the effects of intergenerational trauma on blacks in America who have seen friends and family members murdered at the hands of police and private citizens.

Three African American Men’s Experiences

To give an idea of what living with constant stress and fear is like, I wanted to quote from a recent article that interviewed three African American men living in Spokane, Washington, which is about an hour away from the Abbey.

When asked if they ever feel truly safe, all three men said “no,” and one in particular said “I do not fear any man or profession, but I do fear hate and racism. I carry a registered, concealed firearm with me daily. I position myself with my back to the wall in establishments. I notice every exit point when I enter unknown spaces. I look to see if other Black people are present. I know from my parents and “the talk” that I need to dress, act and behave a certain way in certain spaces or I can become a victim. I have had “the talk” with my two sons because I feel in fear for their safety.”

Another man described what happens when he gets pulled over by police: ‘When I’m getting my license and registration out before the officer gets to my window, I’m rehearsing my tone to make sure it’s not coming off as disrespectful or threatening. I’m sweating. My heart is racing. I’m gripping the steering wheel with both hands. And my voice is shaking while talking to the officer. My concern is making it home to see my family.”

Police Brutality as a Public Health Crisis

Hearing this account, it’s no surprise that police brutality has also been cited as a public health crisis, affecting primarily African Africans. The National Medical Association, which is an organization representing African American physicians and patients in the United States, released a statement in June showing that Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than whites. More unarmed Black people were killed by police than unarmed white people last year, and police killings are the sixth-leading cause of death among men of all races aged 25-29.

COVID-19

The spread of the coronavirus has also uncovered institutionalized racism in U.S. healthcare systems.

COVID-19 data analyzed by NPR showed that African-American deaths from COVID nationwide are nearly two times greater than would be expected based on their share of the population.

Hispanics and Latinos also make up a greater share of confirmed cases than their share of the population in 42 states and Washington D.C.

Health officials stress that higher rates of COVID-19 among minorities are not due to genetic causes, but to rather the impact of public policy decisions that have left communities of color more susceptible to catching the virus and experiencing its worst complications.

Black and Latino people make up a large proportion of “frontline workers” exposed to the coronavirus, yet lack adequate access to testing and treatment. In recent webinar, neuroscientist Richard Davidson said that African-Americans in the 35-45 age range are 10 times more likely to get COVID than Whites.

Black workers make up a disproportionate number of workers who’ve been laid off or business owners who’ve been forced to shut down, which will make access to healthcare difficult in the future.

Why is This a Problem?

So, we may ask ourselves, why as spiritual practitioners should we be concerned with this?

Because we recognize that all sentient beings have an equal right to be happy and to avoid suffering, on both the mundane and transcendental levels.

Especially as Buddhist practitioners, our goal is to cultivate love, compassion, equanimity, and joy for all beings on an equal basis, which goes directly against racist or discriminatory attitudes that view some groups of people as less deserving of love and compassion.

And as practitioners of Mahayana Buddhism, we pledge to lead all sentient beings out of suffering by attaining Buddhahood, which means we need to reach out and support groups that are marginalized by society.

What Can We Do?

So, what can we do to address this situation?

The American Public Health Association released a pamphlet containing many recommendations public officials can adopt in order to improve health equity in the country.

The first recommendation is admitting that health discrepancies actually exist and naming the vulnerable populations that are affected. Applied to the individual level, this means we should not remain silent about discrimination or bigotry and look the other way. As one of the African American Spokanites said, “Silence about racism is just as bad as expressing racism.”

Healthcare professionals and those working in the healthcare industry have a particular responsibility to address racism within their institutions, as well as within themselves.

The pamphlet recognized that health is a result of many causes and conditions that are not necessarily medical, the main ones being education – which is the strongest indicator of lifelong health – employment, and housing and neighborhood conditions. This shows that every person in society plays a role in the health of everyone else.

In this light, we can see that reducing racism in this country has to start with ourselves, by examining our own hearts and minds for any instances of racial bias or prejudice, and taking steps to uproot them. Social movements are good, but they will not have lasting effects unless we are willing to address distorted ways of thinking that allow racism to continue.

Examining our own minds for racist and biased thoughts can be difficult to due shame, but there is an online test by Harvard University that can help determine if you might have implicit bias against certain races, genders, or other categories of people. The good news is that if you do have any implicit bias, meditating on compassion will reduce it, which we learned during a Dalai Lama webcast yesterday on resilience, compassion, and science.

Another way we can work to overcome personal biases and prejudice is by changing how we interact with other people. One non-violent communication counselor the Abbey knows in Portland publishes a weekly newsletter and the topic of the most recent one was “Finding a New Quality of Connection.”

In it, she provided some strategies for developing quality connections with people who are different than us, that include the following elements:

- You recognize the universal humanity in yourself and another.

- You feel care and compassion for your own and another’s experience.

- You feel vulnerable because you are sharing authentically from the heart.

- You feel curious about your own experience or another’s.

- You trust a balance of listening and being heard.

- You prioritize staying connected, and are not willing to sacrifice that connection for the sake of asserting your view or opinion.

If we can approach other people with these attitudes, especially those who are different than us, both are more likely to express what is most meaningful and reach common ground.

In order to develop these types of connection, the newsletter recommended:

- Developing empathy, which involves identifying with the universal needs expressed in others’ stories,

- Acknowledging our own fear, shame, and discomfort, which will allow us to stay grounded and relate from our heart,

- And finding opportunities to step out of our comfort zone and build trust with people or groups in need of support.

Conclusion

In Buddhism, we practice thought training to see the positive aspects of any given situation and use it as an opportunity to increase our wisdom and compassion.

The current spotlight on racism and police brutality in the United States provides an opportunity to not just reform institutions, but to increase love and understanding within our own hearts and minds.

A Rolling Stone article entitled “Racism Kills: Why Many Are Declaring It a Public Health Crisis” pointed out that one benefit of the COVID outbreak is that we’re finally getting used to thinking of health in terms of interconnectedness, rather than solely on an individual basis. And we can expand this understanding of interconnectedness to whatever activities we engage in each day.

Perhaps the most uplifting aspect of addressing racism is that it will benefit all sentient beings, no matter what color they are. This is reflected in a quote by Emilia Sykes, the Ohio Minority House Leader mentioned earlier, who said “Addressing racism as a public crisis won’t just help black people — it’ll help every single person in this country. This is not ‘Us versus Them.’ It’s Us versus Oppression, Us versus Alienation, Us versus Hatred. There shouldn’t be any reason why people can’t grasp this and want to support it because this is supporting every human being.”

So, whatever steps we decide to take to reduce racism, may we see it as one the many causes that will help us achieve full awakening for the benefit of all sentient beings.

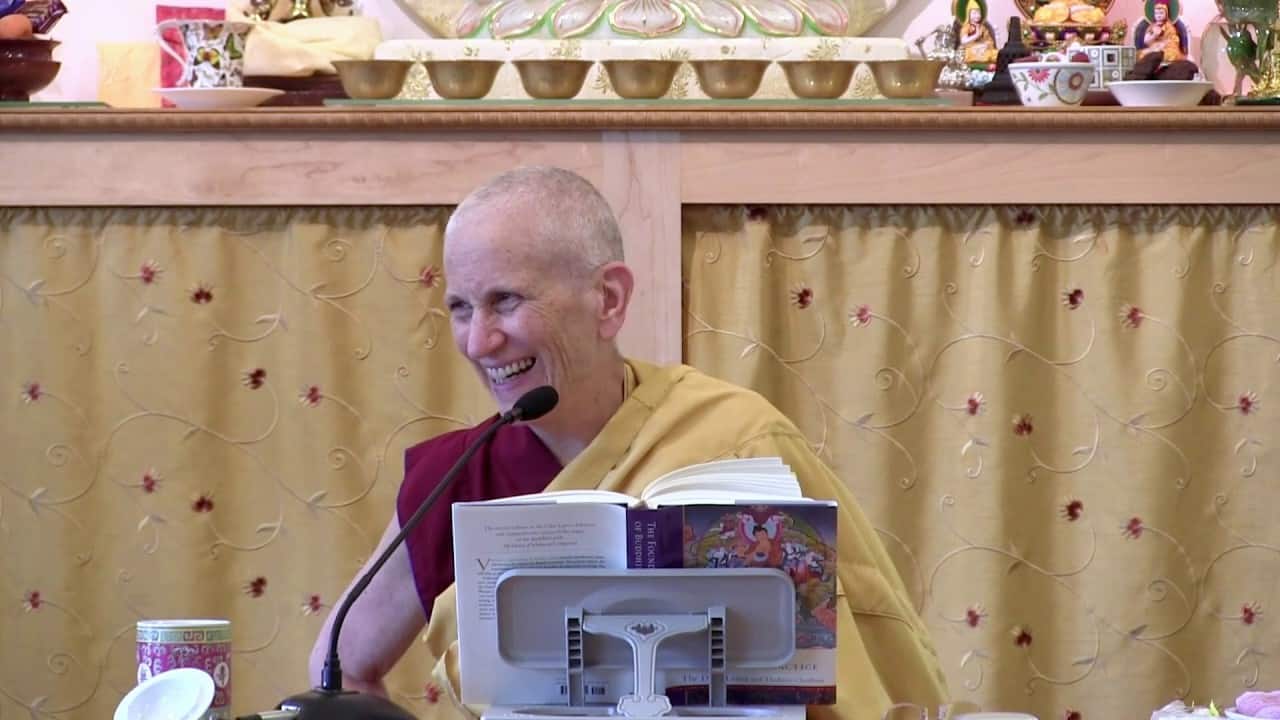

Venerable Thubten Kunga

Venerable Kunga grew up bi-culturally as the daughter of a Filipino immigrant in Alexandria, Virginia, just outside Washington, DC. She received a BA in Sociology from the University of Virginia and an MA from George Mason University in Public Administration before working for the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Refugees, Population, and Migration for seven years. She also worked in a psychologist’s office and a community-building non-profit organization. Ven. Kunga met Buddhism in college during an anthropology course and knew it was the path she had been looking for, but did not begin seriously practicing until 2014. She was affiliated with the Insight Meditation Community of Washington and the Guyhasamaja FPMT center in Fairfax, VA. Realizing that the peace of mind experienced in meditation was the true happiness she was looking for, she traveled to Nepal in 2016 to teach English and took refuge at Kopan Monastery. Shortly thereafter she attended the Exploring Monastic Life retreat at Sravasti Abbey and felt she had found a new home, returning a few months later to stay as a long-term guest, followed by anagarika (trainee) ordination in July 2017 and novice ordination in May 2019.